Introduction

The frontal, ethmoidal, sphenoid, zygomatic, and lacrimal bones comprise the bony structures of the orbit (see Image. Orbit Anterior View). The maxillary and lacrimal bones form the lacrimal fossa medially. These bones also form the medial wall together with the lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone. The sphenoid bone forms the posterior wall and houses the orbital canal. Cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI pass lateral to the orbital canal via the superior orbital fissure. The zygomatic bone forms the lateral wall. The frontal and maxillary bones form the superior and inferior orbital borders.

The 6 extraocular muscles are located inside the orbit, attached to the globe. The extraocular muscles include 4 rectus and 2 oblique muscles. The fat and connective tissue surrounding the globe help reduce the pressure exerted by the extraocular muscles.[1][2]

The orbital bones are thin and delicate, with varying shapes, making them prone to fractures from relatively minor trauma. Orbital floor fractures can involve single or multiple bones within the orbit, leading to diverse fracture patterns. Additionally, the orbit is close to vital intracranial structures. These attributes require that the healthcare provider thoroughly understands orbital anatomy and prudently uses diagnostic tools to properly manage patients with orbital fractures. Collaboration among various specialists is likewise often necessary to ensure good outcomes. Tailoring treatment plans based on the specific fracture pattern, severity, and associated injuries minimize potential complications.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A blowout fracture is an isolated fracture of the orbital walls without compromising the orbital rims.[3] Common mechanisms include falls, high-velocity ball-related sports, traffic accidents, and interpersonal violence. A blunt, directed force is often aimed at the eye without a pressure component toward the eye rim. A hydraulic mechanism may occur, wherein intraorbital pressure increases after a fracture in the area. Alternatively, a buckling mechanism may cause the fracture when the force is directed toward the orbital rim.[4][5]

Pediatric patients may experience a "trapdoor fracture" rather than a blowout fracture after orbital trauma. The fractured orbital floor returns to its original position due to the young bone's softness, potentially entrapping orbital soft tissues. Trapdoor fractures may present with minimal or absent external signs of trauma, hence the term "white-eyed blowout." By comparison, classic blowout fractures in adults exhibit visible soft tissue changes, such as enophthalmos or a sunken eye.

Epidemiology

Orbital fractures are more common in males than females and most often occur between the ages of 21 and 30 years.[6] The orbital floor and medial orbital wall are the most common fracture sites.[7] Falls, motor vehicle accidents, and assaults account for most midfacial fractures.[8][9][10]

Pathophysiology

Orbital blowout fractures typically result from trauma. The force may be transmitted directly or create great intraorbital pressure until the thin bones of the orbital floor and medial wall break. Blowout fractures may result in herniation or entrapment of orbital contents. Extraocular muscle entrapment can cause eye movement limitations, pain, diplopia, optic nerve compression, and visual disturbances.

In severe cases, compartment syndrome may arise from increased intraorbital pressure, impairing orbital circulation and producing ischemic damage.

History and Physical

As in any other conditions arising from head trauma, patients with suspected blowout fractures may come into the emergency department conscious or unconscious. Unconscious individuals need immediate medical attention and, possibly, resuscitation. Life-threatening injuries must be ruled out before proceeding with a full evaluation.

Once emergencies have been ruled out, the provider may begin taking a complete history, asking about the mechanism and time of injury and symptom onset. The patient may report visual changes, headache, dizziness, orbital pain or numbness, swelling, and eye and eyelid movement difficulties.

The periorbital area must be inspected for swelling, bruising (ecchymosis), deformity, enophthalmos, asymmetry, hyphema, or skin lacerations on physical examination. Eye function may be assessed by checking visual acuity, ocular alignment, and extraocular muscle movements. Ophthalmoscopy should be performed to look for evidence of internal eye injury, such as retinal detachment. Globe rupture should be suspected in the presence of eye pain and decreased visual acuity.

Careful orbital palpation may reveal bone irregularities that help localize the orbital fracture. The nose must be checked for septal hematoma. Clinical examination must rule out large fractures at risk of enophthalmos, infraorbital structure entrapment, and optical neuropathy, which need acute intervention.

The following findings are characteristic of orbital floor fractures and warrant further imaging:[11]

- Diplopia on upward gaze

- Limitation of upward gaze

- Tenderness or step-offs at the infraorbital rim

- Absent pupillary light reflex

- Poor visual acuity

- Chemosis and subconjunctival hemorrhage

- Edema and periorbital ecchymosis

Findings associated with damage to specific structures include the following:

- Decreased sensation over the inferior orbital rim that may extend nasolabially signifies trigeminal nerve damage

- Subcutaneous emphysema is a sign of a maxillary sinus fracture

- Inferior rectus entrapment between inferior orbital fragments may have associated oculomotor nerve palsy

- Enopthalmos, exophthalmos, or swelling behind the globe indicates displacement of the fractured orbital bones

Early referral to an ophthalmologist or orbital specialist may be necessary for further evaluation and treatment planning.

Evaluation

Imaging tests help differentiate orbital floor fractures from the following related conditions:

- Medial or lateral wall fractures

- Orbito-zygomatic fractures

- LeFort I, II, and III fractures

- Nasoorbital ethmoidal fractures (Markowitz fractures)

Plain radiographs can help identify an orbital floor fracture in the presence of the following findings:

- Subcutaneous emphysema

- Soft-tissue teardrop along the roof of the maxillary sinus

- Air-fluid level in the maxillary sinus

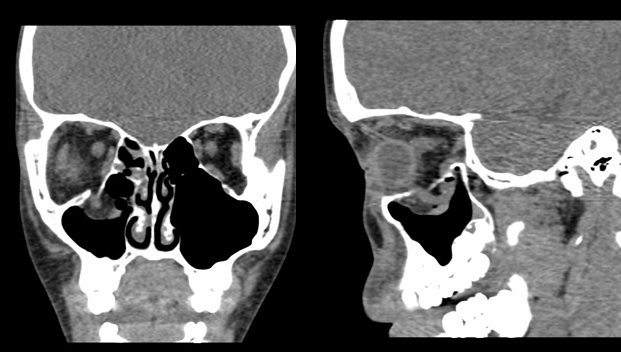

Computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality of choice when searching for or evaluating a blowout fracture. A CT scan may reveal orbital fat or inferior rectus muscle herniation into the maxillary sinus (see Image. Orbital Floor Fracture Computed Tomography). This modality can also detect occult tears and retained foreign bodies if present.

Preoperative blood work should include CBC, electrolytes, coagulation profile, and a pregnancy test (for females) if surgery is considered.

Treatment / Management

The primary goal of orbital fracture treatment is to restore aesthetics and function. Some cases may be managed conservatively, while others require surgery. All patients with orbital fractures must be given prophylactic antibiotics, covering for oral organisms. Corticosteroids may help reduce the edema. Patients should be discouraged from blowing the nose or performing a Valsalva maneuver, which may worsen orbital emphysema.

The goal of surgery is to restore herniated structures into the orbital cavity. The preferred approaches are transconjunctival or transmaxillary. Several implant types are available for orbital reconstruction, though implantation must be avoided in the presence of an infection. Endoscopic techniques are also available for orbital fracture repair.

Immediate surgical intervention is necessary for children with trapdoor fractures and vital sign instability, retrobulbar hematoma with progressive visual acuity loss, and enophthalmos of more than 2 mm on initial evaluation.[12](B3)

Relative indications for immediate surgery include entrapment of orbital structures without vital sign instability, persistent diplopia, enophthalmos, hypoglobus, and disruption of more than 50% of the orbital floor's surface area.[13] However, surgery is postponed for most of these patients until after the initial edema has subsided and the injury has been examined more thoroughly. An open-globe injury should be treated emergently, and repair of the orbital floor fracture should be delayed by a few weeks until the globe is stable.(B3)

Generally, surgery must be performed within 14 days of injury to prevent fibrosis. Most surgeons wait 24 to 72 hours to allow the edema to subside. Children with orbital fractures and oculomotor dysfunction generally have more favorable outcomes if surgery is performed within 7 days post-injury. If the patient's only complaint is infraorbital nerve dysfunction, the decision to repair requires judgment and experience. Some surgeons report good results with an early repair.[14] (B3)

Visual acuity, extraocular motor function, diplopia, enophthalmos degree, and dysesthesia presence should be documented before an orbital fracture repair procedure. During surgery, pupillary function must be serially assessed. The anesthesiologist must avoid medications that may cause pupillary constriction or dilatation. The anesthesiologist must also know that bradycardia may arise from extraocular muscle manipulation due to the oculocardiac reflex.

Nondisplaced orbital floor fractures may be treated nonsurgically, especially without acute orbital volume changes. Relative contraindications for surgery include hyphema, retinal tears, globe perforation, and medical instability.[15]

Differential Diagnosis

The following conditions may be confused with an orbital fracture in the presence of periorbital swelling, visual changes, and extraocular muscle dysfunction:

- Soft tissue edema secondary to trauma

- Abducens nerve palsy

- Traumatic diplopia

- Compressive optic neuropathy

- Oculomotor nerve palsy

- Trochlear nerve palsy

A thorough medical evaluation will help distinguish orbital fractures from these disorders.

Prognosis

The prognosis for orbital floor fractures depends on the problem's complexity, the presence of other injuries or medical conditions, promptness of treatment, and individual variations in healing. Generally, single-bone fractures with minimal displacement and trapdoor fractures have a better prognosis than complex fractures involving multiple bones or significant displacement.

The presence of other injuries or medical conditions can dictate the timing of surgical interventions. Prompt treatment prevents complications, producing better outcomes. Orbital bones typically heal well with appropriate treatment and rehabilitation unless the patient has a medical condition that can delay recovery, such as uncontrolled diabetes. Visual recovery also depends on the same factors.

Overall, many patients with orbital fractures achieve satisfactory outcomes with appropriate medical or surgical intervention. Early referral to an ophthalmologist or orbital specialist is crucial for individualized management and improving prognosis.

Complications

Acute surgical complications include loss of vision due to retrobulbar hematoma or impingement of the orbital apex. Delayed surgical complications include entropion, ectropion, diplopia, infraorbital paresthesia, enophthalmos, and blindness, depending on the technique used. Prompt specialist referral and intervention help prevent complications.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

During postoperative care, the examiner should watch out for postoperative complications such as infection and visual or neurologic symptoms. Visual acuity and pupillary function must be monitored closely, as deterioration may warrant a secondary procedure. The patient must be advised to elevate the head or sit upright to reduce edema. Cool compresses can help reduce pain and swelling on the surgical site.

During initial rehabilitation, the patient must be advised to rest and avoid strenuous activities to promote proper healing. A protective shield or eye patch may be recommended to prevent accidental trauma or further injury to the affected eye. Patients must have adequate pain control before starting therapy sessions.

Proper eye care instructions should be provided, particularly on cleaning the affected eye, using eye medications, and maintaining general eye health. Vision therapy or exercises may be recommended for patients with impaired vision or diplopia to help the eyes regain alignment and coordination.

As healing progresses, patients may be allowed a gradual return to normal activities. Regular follow-up with an ophthalmologist is essential to monitor healing progress, assess for complications, and manage any ongoing symptoms.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing orbital fractures primarily involves taking precautions to reduce the risk of facial trauma or injuries to the eye region. Patients may take several measures to prevent orbital floor fractures.

First is to wear protective gear during high-risk activities such as sports, construction work, and riding a motorcycle. Helmets, masks, safety goggles, and face shields may be used where appropriate. The second is to implement fall-prevention strategies for at-risk individuals. For example, non-slip flooring material may be used in areas where young children and older individuals frequently stay.

The third is to drive safely. Wearing seat belts and obeying traffic rules reduce the risk of motor vehicular crashes that can cause facial injuries. Fourth is to have regular eye examinations. Early detection and correction of visual problems can prevent falls. Fifth is to maintain healthy social relationships, preventing altercations that can lead to physical assault and facial trauma.

Not all facial injuries can be prevented. However, taking proactive steps to minimize risks can significantly reduce the likelihood of sustaining an orbital fracture.

Pearls and Other Issues

The following are the key points in managing orbital fractures:

- Diplopia with upward gaze, limited upward gaze, infraorbital anesthesia, and enophthalmos are hallmarks of blowout fractures and need a referral for surgical evaluation.

- Early ophthalmologic consultation is mandatory.

- CT scan is the imaging modality of choice for orbital fractures.

- Immediate surgery is warranted in blowout fractures with associated vital sign instability, retrobulbar hematoma with progressive visual acuity loss, severe enophthalmos, and open globe injury.

- Nondisplaced orbital floor fractures may be treated nonsurgically, especially if no acute orbital volume changes exist.

- Observation of uncomplicated fractures is recommended for up to 2 weeks. After that period, a decision can be made whether the patient needs surgery.

- The prognosis is good for promptly treated simple, nondisplaced orbital floor fractures.

Tailoring the treatment plan to the individual's condition is essential for successful recovery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach to blowout fractures is recommended. The members of the team include the following:

- Emergency medicine physician: The first provider the patient will likely consult about an acute blowout fracture. The emergency medicine physician is the first to evaluate the injury, provide treatment, and initiate specialist referrals.

- Radiologist: This team member interprets the imaging tests, which is crucial to management.

- Ophthalmologist: All patients suspected of orbital fractures must see an ophthalmologist on presentation to the emergency department and before surgery.

- Otolaryngologist, facial plastic surgeon, ocular plastic surgeon, or maxillofacial surgeon: These orbital specialists can perform surgery if needed and determine the type that can lead to the best outcomes.

- Nurses: Nursing care is critical during and after surgery. These professionals administer medications, monitor vital signs and neurologic status, and ensure patients are comfortable and adhere to pretreatment care instructions. Nurses report abrupt changes in vital signs and neurologic status to the primary service caring for the patient.

- Rehabilitation specialists: Physical and occupational therapists help patients return to their previous function and resume their normal routines.

- Primary care physician: This provider monitors the patient's posttreatment progress and provides counseling for preventing orbital fracture recurrence.

Close communication with all the staff is vital to improve patient outcomes.[16]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Orbit, Anterior View. Shown in this illustration are the supraorbital notch, ethmoidal foramina, optic foramen, superior orbital fissure (hourglass configuration), greater wing of the sphenoid bone, zygomaticofacial foramen, inferior orbital fissure, infraorbital groove, zygomaticomaxillary suture, infraorbital foramen, infraorbital suture, posterior lacrimal crest, anterior lacrimal crest, frontomaxillary suture, and lamina papyracea. The walls of the orbit include the frontal bone superiorly; ethmoid, frontal, lacrimal, and sphenoid bones medially; maxilla, zygomatic, and palatine bones inferiorly; and zygomatic and sphenoid bones laterally.

Johannes Sobotta, MD, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hopper RA, Salemy S, Sze RW. Diagnosis of midface fractures with CT: what the surgeon needs to know. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2006 May-Jun:26(3):783-93 [PubMed PMID: 16702454]

Linnau KF, Stanley RB Jr, Hallam DK, Gross JA, Mann FA. Imaging of high-energy midfacial trauma: what the surgeon needs to know. European journal of radiology. 2003 Oct:48(1):17-32 [PubMed PMID: 14511857]

Felding UNA. Blowout fractures - clinic, imaging and applied anatomy of the orbit. Danish medical journal. 2018 Mar:65(3):. pii: B5459. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29510812]

Schaller A, Huempfner-Hierl H, Hemprich A, Hierl T. Biomechanical mechanisms of orbital wall fractures - a transient finite element analysis. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2013 Dec:41(8):710-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.02.008. Epub 2012 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 22417768]

Ahmad F, Kirkpatrick NA, Lyne J, Urdang M, Waterhouse N. Buckling and hydraulic mechanisms in orbital blowout fractures: fact or fiction? The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2006 May:17(3):438-41 [PubMed PMID: 16770178]

Shin JW, Lim JS, Yoo G, Byeon JH. An analysis of pure blowout fractures and associated ocular symptoms. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2013 May:24(3):703-7. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31829026ca. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23714863]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJoseph JM, Glavas IP. Orbital fractures: a review. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2011 Jan 12:5():95-100. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S14972. Epub 2011 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 21339801]

Emodi O, Wolff A, Srouji H, Bahouth H, Noy D, Abu El Naaj I, Rachmiel A. Trend and Demographic Characteristics of Maxillofacial Fractures in Level I Trauma Center. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Mar:29(2):471-475. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004128. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29194270]

Francis DO, Kaufman R, Yueh B, Mock C, Nathens AB. Air bag-induced orbital blow-out fractures. The Laryngoscope. 2006 Nov:116(11):1966-72 [PubMed PMID: 17075425]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRunci M, De Ponte FS, Falzea R, Bramanti E, Lauritano F, Cervino G, Famà F, Calvo A, Crimi S, Rapisarda S, Cicciù M. Facial and Orbital Fractures: A Fifteen Years Retrospective Evaluation of North East Sicily Treated Patients. The open dentistry journal. 2017:11():546-556. doi: 10.2174/1874210601711010546. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29238415]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKaufman Y, Stal D, Cole P, Hollier L Jr. Orbitozygomatic fracture management. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008 Apr:121(4):1370-1374. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000308390.64117.95. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18349658]

Pham CM, Couch SM. Oculocardiac reflex elicited by orbital floor fracture and inferior globe displacement. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2017 Jun:6():4-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2017.01.004. Epub 2017 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 29260043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDutton JJ. Management of blow-out fractures of the orbital floor. Survey of ophthalmology. 1991 Jan-Feb:35(4):279-80 [PubMed PMID: 2011821]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurnstine MA. Clinical recommendations for repair of orbital facial fractures. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2003 Oct:14(5):236-40 [PubMed PMID: 14502049]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim HS, Jeong EC. Orbital Floor Fracture. Archives of craniofacial surgery. 2016 Sep:17(3):111-118. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2016.17.3.111. Epub 2016 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 28913267]

Noda M, Noda K, Ideta S, Nakamura Y, Ishida S, Inoue M, Tsubota K. Repair of blowout orbital floor fracture by periosteal suturing. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2011 May-Jun:39(4):364-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02441.x. Epub 2010 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 20973893]