Definition/Introduction

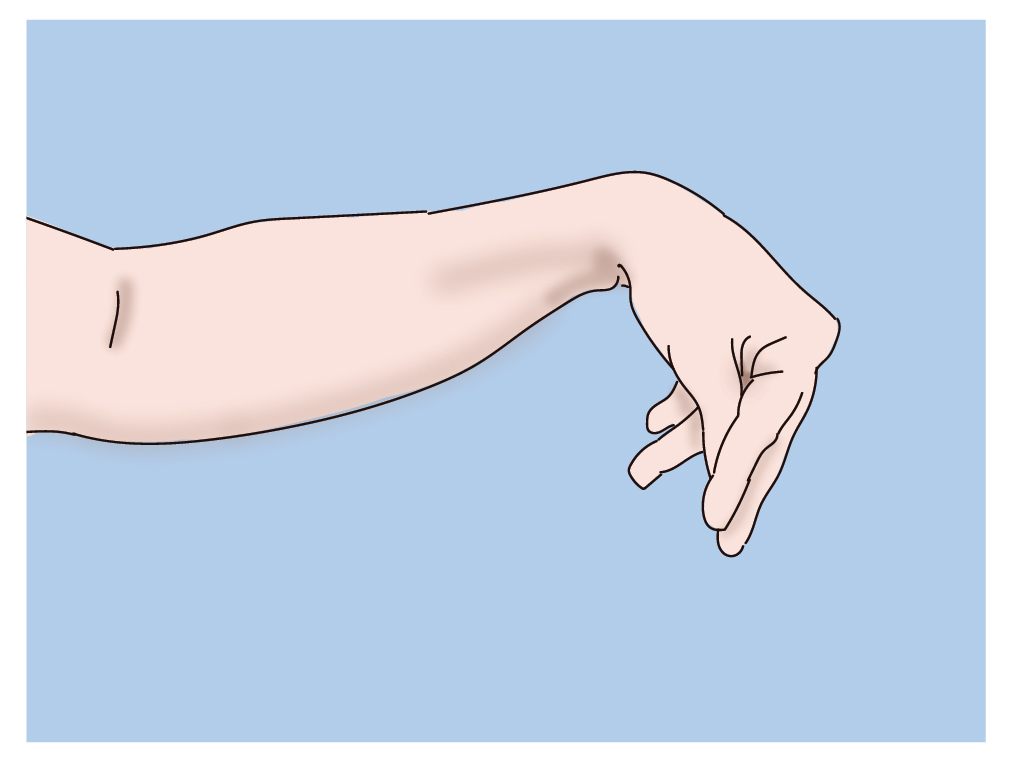

Trousseau’s sign for latent tetany is most commonly positive in the setting of hypocalcemia.[1] The sign is observable as a carpopedal spasm induced by ischemia secondary to the inflation of a sphygmomanometer cuff, commonly on an individual’s arm, to 20 mmHg over their systolic blood pressure for 3 minutes.[1] The carpopedal spasm is visualized as flexion of the wrist, thumb, and metacarpophalangeal joints with hyperextension of the fingers.[1]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

The normal level of calcium in the blood is between 8.5 to 10.5 mg/dL.[2] The sensitivity and specificity of Trousseau’s sign for individuals with hypocalcemia are reported to be 94 percent and 99 percent, respectively.[2][3] Despite this, one to four percent of healthy individuals may have a positive Trousseau’s sign.[3] Trousseau’s sign may also be elicited in the setting of hypomagnesemia and metabolic alkalosis, such as in the context of hyperventilation or excessive acid loss through the gastrointestinal system.[4] In both of these cases, however, hypocalcemia tends also to be present.

Hypocalcemia can present in numerous conditions, most commonly in the setting of vitamin D deficiency or hypoparathyroidism.[5] Medications, commonly bisphosphonates such as zoledronic acid used in the treatment of osteoporosis, and cisplatin, a chemotherapeutic, among others, are also common culprits.[6] Individuals with life-threatening conditions such as sepsis, hemorrhagic shock, rhabdomyolysis, and tumor lysis syndrome may also develop hypocalcemia. In sepsis, a condition that occurs secondary to one’s own immune response to microbial infection, hypocalcemia is hypothesized to occur secondary to a problem along the parathyroid-vitamin D axis.[7] Examples include acquired parathyroid gland insufficiency, calcitriol resistance, or vitamin D insufficiency secondary to a nutritional deficit or a lack of conversion to its active form secondary to a deficiency in renal 1-alpha-hydroxylase.[7] In the case of hemorrhagic shock, hypocalcemia stems from calcium chelation by the anticoagulant storage solution (sodium citrate) in packed red blood cells.[8] In both rhabdomyolysis and tumor lysis syndrome, the hypocalcemia is secondary to phosphate overload in the setting of cell destruction.[9][10] These individuals can potentially develop torsades de pointes, ventricular tachycardia, or complete heart block due to prolongation of their QT interval secondary to the plateau phase of the cardiac action potential being prolonged.[11][12]

Clinical Significance

Through the utilization of a thorough history and physical exam, healthcare practitioners may be able to discover if a patient has hypocalcemia early in their presentation to a healthcare facility after finding Trousseau’s sign during blood pressure measurement, allowing for rapid intervention.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Vital signs are often obtained at the beginning of a patient encounter, frequently by a nurse, certified nursing assistant, or medical assistant. Therefore, Trouseeau's sign may commonly be noted by the allied health professional taking the vital signs, rather than by the clinician. Recognition of the sign and communication to the clinician may be the only opportunity for the patient to have this issue addressed.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Young P, Bravo MA, González MG, Finn BC, Quezel MA, Bruetman JE. [Armand Trousseau (1801-1867), his history and the signs of hypocalcemia]. Revista medica de Chile. 2014 Oct:142(10):1341-7. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872014001000017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25601121]

van Bussel BC, Koopmans RP. Trousseau's sign at the emergency department. BMJ case reports. 2016 Aug 1:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216270. Epub 2016 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 27481262]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJesus JE, Landry A. Images in clinical medicine. Chvostek's and Trousseau's signs. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Sep 13:367(11):e15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1110569. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22970971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilliams A, Liddle D, Abraham V. Tetany: A diagnostic dilemma. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2011 Jul:27(3):393-4. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.83691. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21897517]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFeingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Schafer AL, Shoback DM. Hypocalcemia: Diagnosis and Treatment. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25905251]

Liamis G, Milionis HJ, Elisaf M. A review of drug-induced hypocalcemia. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2009:27(6):635-42. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0119-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19730969]

Zaloga GP, Chernow B. The multifactorial basis for hypocalcemia during sepsis. Studies of the parathyroid hormone-vitamin D axis. Annals of internal medicine. 1987 Jul:107(1):36-41 [PubMed PMID: 3592447]

Li K, Xu Y. Citrate metabolism in blood transfusions and its relationship due to metabolic alkalosis and respiratory acidosis. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2015:8(4):6578-84 [PubMed PMID: 26131288]

Davis AM. Hypocalcemia in rhabdomyolysis. JAMA. 1987 Feb 6:257(5):626 [PubMed PMID: 3795440]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilliams SM, Killeen AA. Tumor Lysis Syndrome. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2019 Mar:143(3):386-393. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0278-RS. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30499695]

Chhabra ST, Mehta S, Chhabra S, Singla M, Aslam N, Mohan B, Wander GS. Hypocalcemia Presenting as Life Threatening Torsades de Pointes with Prolongation of QTc Interval. Indian journal of clinical biochemistry : IJCB. 2018 Apr:33(2):235-238. doi: 10.1007/s12291-017-0684-z. Epub 2017 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 29651218]

Nijjer S, Ghosh AK, Dubrey SW. Hypocalcaemia, long QT interval and atrial arrhythmias. BMJ case reports. 2010:2010():bcr0820092216. doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2216. Epub 2010 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 22242081]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence