Introduction

D-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is an indolamine compound of the lysergamide class known for having powerful psychedelic effects on humans. Although first synthesized in 1938 by Albert Hofmann in an attempt to create a central nervous system stimulant, it was not until 1943 when Hofmann discovered the molecule’s subjective effects on the human body after accidental absorption through the skin. Only a few days later, reports suggested Hofmann ingested around 250 μg of the drug, marking the first intentional “LSD trip.” Hofmann and numerous subsequent individuals, having consumed the drug at different dosages, describe a diverse range of effects. However, a shared element is the profound nature of the experience elicited by the drug in users.

A substance of significant pharmacological and clinical interest, LSD was historically the most researched hallucinogen. In the 1950s, the Central Intelligence Agency famously studied LSD through the research program MK-ULTRA to investigate potential methods and pharmacological agents for developing “truth serums.” Researchers conducted additional studies on the substance’s mechanism of action, ultimately confirming the early belief that it possessed serotonergic properties. Specifically, the drug acts as a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT6 receptors.[1] The threshold dose of LSD is commonly accepted at 15 μg. A relatively heavy dose at the opposite end of the accepted spectrum is around 300 μg. As the dosage increases beyond this arbitrary setpoint, reports suggest an increase in the intensity of the drug’s effects. This dosing brings an all-important question that applies to any substance under scrutiny: pharmacologically speaking, what is the drug’s toxicity? No deaths have been attributed to LSD’s direct effects.[2] Researchers in the last century conducted studies on the therapeutic use of LSD under experimental conditions that today’s standards consider insufficient.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Possession of LSD became illegal in the United States on October 24, 1968, in an amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938.[3] The final study of LSD approved by the Food and Drug Administration took place in 1980. LSD currently sits on a shortlist of schedule I drugs, along with other hallucinogens and stimulants such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT), gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), heroin, marijuana, methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), mescaline, and psilocybin.[3] Clinical trials have been difficult to organize because of the substance’s controversy and status as a controlled substance. There are currently projects under development in Spain, Israel, and the USA researching psilocybin and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in treating post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression associated with cancer.[4][5]

Alexander Shulgin, in his work, “Tryptamines I Have Known and Loved (TiHKAL),” detailed the synthesis of LSD from lysergic acid (classified as a schedule III controlled substance). He describes LSD as “a fragile molecule…free from air and light exposure; it is stable indefinitely.” Shulgin details 3 groups of LSD analogs that have been synthesized; the first group kept the diethylamide group unchanged, with alterations made in the pyrrole ring, and included ALD-52, MLD-41, BOL-148, 1-hydroxymethyl-LSD, 1-dimethyl aminomethyl-LSD, 2-iodo-LSD. The other group of analogs had 1-substituents and amide alkyl group variations and included LAE-32, ergonovine, methergine, DAM-57, LSM-775, and others. The third group included LSD analogs with structural modifications at the 6-position in the “D-ring” and were labeled as constituents of the “LAD series.” According to Shulgin, ETH-LAD, AL-LAD, and PRO-LAD were considered significant and earned separate entries in his book.

A study published in 2016 by De Gregorio et al analyzed the therapeutic potential of novel antipsychotics through the model of LSD-induced psychosis. Their paper includes a summary of experiments highlighting the interactions of LSD with serotonergic, dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and trace amine-associated receptor (TAAR) systems. The summary shows that LSD is not only active at the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C serotonergic receptors and serotonin transporter (SERT) but also active at the D1, D2, D4 dopaminergic receptors, the NMDA, mGlu2/mGlu3 glutamatergic receptors, and the TAAR1 receptor.[6]

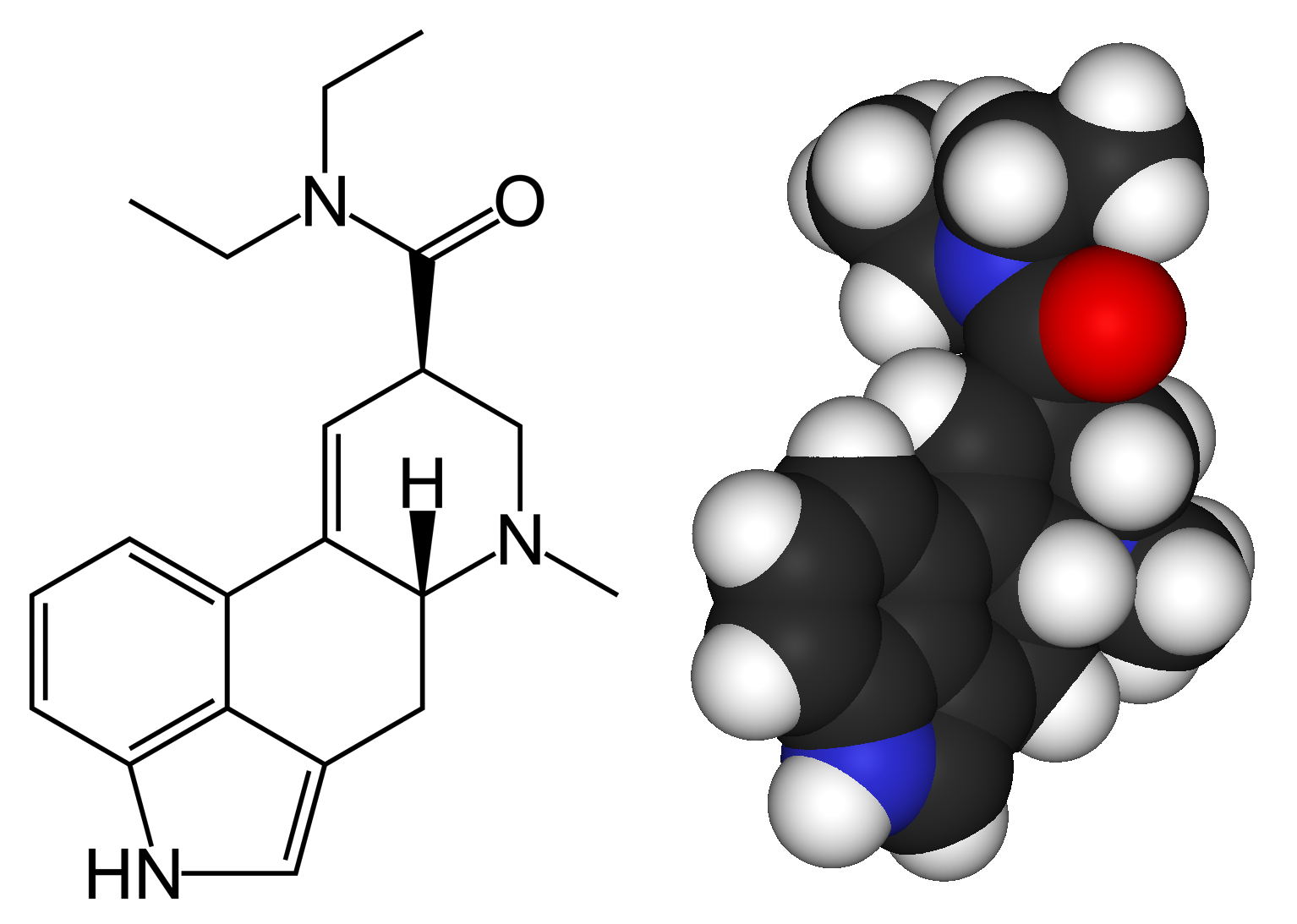

LSD is most commonly ingested orally in blotter, perforated sheets of paper decorated with abstract artwork that can be subdivided into smaller pieces with the substance uniformly laid across the sheet. LSD is also distributed as small pills (microdot) and a solution. LSD has a bioavailability of 71%, a threshold dose of 15 μg, and a duration of action of 8 to 12 hours, with residual effects sometimes lasting anywhere from 12 to 48 hours.[7] It is known as a “club drug.” However, many users prefer to ingest it in a highly controlled, comfortable home setting. See Image. Chemical Structure of LSD.

Epidemiology

A 2013 study conducted by Krebs and Johansen sought to estimate the lifetime prevalence of psychedelic use. They defined psychedelics as either LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, or peyote and described prevalence by age category from a retrospective US population survey. The 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) cited the study. This survey takes place annually to estimate general substance use and potential correlations with mental health indicators from a randomly selected group of individuals 12 years and up. In the 2010 survey, 23 million US residents reported using LSD at least once (23 million, 95% CI: 22 to 25 million). Use among residents in the 50 to 64-year age group was similar to those in the 21 to 49-year age group. Interestingly, the rate of lifetime psychedelic use was most prominent among those 30 to 34 years; recreational LSD use first became prevalent during the 1960s and 1970s.[8]

Rickert et al looked at the prevalence and risk factors for LSD use among young women in a study first published in 2003; 904 sexually active adolescent and young adult women 14 to 26 years of age took the survey at university-based outpatient reproductive health clinics between April and November 1997. Out of 904 participants, 119 (13%) reported using LSD at least once, and 536 (58%) reported using marijuana at least once. Further analyses showed that the typical female LSD or marijuana user presented with a distinct profile: women who reported alcohol intoxication at least 10 times in the past year, smoked at least half a pack of cigarettes within the same timeframe, and those who identified themselves as being relatively “high-sexual-risk takers” were more likely to have used LSD or marijuana in the past. LSD users, in contrast to nonusers, however, were more likely to be of white ethnicity, present under the age of 17, and were more likely to report a history of physical abuse and severe depressive symptoms.[9]

Toxicokinetics

Dolder et al analyzed the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of LSD in a study published in 2017.[6] The analysis occurred in 2 studies: in one newly performed study, 100 μg of LSD was dosed orally to 24 healthy subjects; in the other study, which was a retrospective analysis, 16 subjects received 200 μg orally. Blood sampling was performed, and analysis of plasma LSD concentrations, subjective moods of the subjects, and vital signs was also recorded. Results from the study showed that the plasma half-life of LSD was 2.9 hours, comparable to the result after IV administration of 2 μg/kg found in a separate study. In the 100 μg dose group, the researchers found the time of onset to be 0.8 ± 0.4 hours (range 0.1 to 1.7 hours) and 9.0 ± 2.0 hours (range 6.1 to 14.5 hours); the mean effect duration was measured as 8.2 ± 2.1 h (range 5 to 14 hours); time to peak drug effect was 2.8 ± 0.8 hours (range 1.2 to 4.6 hours). For the 200-μg dose group, the following values were obtained: for the time of onset and offset, 0.4 ± 0.3 h (range 0.04 to 1.2 hours) and 11.6 ± 4.2 hours (range 7.0 to 19.5 hours), mean effect duration was 11.2 ± 4.2 hours (range 6.4 to 19.3 hours), and time to peak effects was 2.5 ± 1.2 hours (range 0.8 to 4.4 hours). The researchers found systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and core body temperature elevated after LSD administration in both groups.

| Dose | Time of onset (h) | Time to peak effect (tmax, h) | Half-life (t1/2, h) | Mean effect duration (h) | Time of offset |

| 100 μg | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 2.6 | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 9.0 ± 2.0 |

| 200 μg |

0.4 ± 0.3 |

2.5 ± 1.2 hours | 2.6 | 11.2 ± 4.2 | 11.6 ± 4.2 |

History and Physical

Patients under the influence of LSD will most likely present to a clinical setting after experiencing what is colloquially referred to as a “bad trip.” Others may present unknowingly or in exceedingly large doses after ingesting the substance.

Obtaining a quality history and physical depends on the alertness and orientation of the presenting patient, which will vary based on how altered the patient’s perception appears. Clinical staff should contact any friends or family to assist if the patient cannot provide a thorough history. Clinicians should focus history taking on the following: chief complaint(s), the dosage of substance, timing, and place of dosage, patient’s knowledge of the substance, prior experience with substance, associated symptoms or concomitant substance use, and standard review of systems.

The following may appear on the physical exam:

- Vitals: normal to high temperature, hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnea, increased or decreased oxygen saturation

- General: altered mental status, diaphoresis, disheveled appearance, loss of appetite

- HEENT: mydriasis, xerostomia, nystagmus

- Respiratory: tachypnea

- Cardiovascular: tachycardia, hypertension

- Skin: hyperhidrosis

- Neurologic: impaired coordination

- Psychiatric: auditory and visual hallucinations, panic, psychosis, paranoia, synesthesia (a “blending of the senses”), distortion of time, emotional lability, aggression, depersonalization, suicidal ideation, religiosity, depression

Evaluation

The diagnosis of LSD intoxication is clinical. A thorough history and physical require emphasis; this is not to say other testing modalities are unnecessary. Coagulation studies and serum electrolytes should be obtained in complicated cases, especially when seizures or neuroleptic malignant syndrome are suspected. Imaging studies are warranted to rule out other diagnoses. Electrocardiography is appropriate to evaluate tachycardias, bradycardias, and other arrhythmias; these conditions are not necessarily caused by LSD itself but possibly from co-ingestion with other potent stimulants, such as MDMA.

A routine drug test does not detect the substance. However, a recent study in 2015 by Dolder et al. sought to quantify LSD and its main metabolite, 2-oxo-3-hydroxy LSD (abbreviated as O-H-LSD), in the serum and urine samples, primarily in the emergency setting. Their methods were accurate and precise in quantifying the expected concentrations in subjects intoxicated by LSD, but their approach has not found wide adoption in clinical settings.[10]

Berg et al used ultra-performance liquid chromatography to determine concentrations of LSD in serum in a 2013 study. Concentrations of 1.5 to 5.5 ng/mL were present 24 hours after patients ingested 300-μg doses. Due to the complexity surrounding the methods, they are not adopted universally.[11]

Treatment / Management

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) published protocols for improving treatment for patients under the influence of or withdrawing from specific substances in a 2006 update. For hallucinogenic toxicity, the recommendation is to provide a quiet environment for the patient, preferably free from external stimuli, and to provide 1:1 supervision to ensure the patient does not cause any harm to themselves or others. The guidelines also state that a low dose of benzodiazepine may sometimes be indicated to control anxiety. Individuals who have taken large doses of LSD are at risk for residual psychotic symptoms and are therefore managed with antipsychotic drugs if symptoms manifest and persist.[12] Treatment of LSD toxicity is mainly supportive. Autonomic symptoms may require symptomatic treatment (see Table 2).

Table 2. Key steps in Managing LSD intoxication

| Key Steps | Management |

| 1. Assessment and Stabilization | - Address immediate life-threatening conditions- Treat airway obstruction or cardiovascular instability- Check for hypoglycemia with point-of-care testing |

| 2. Supportive Care | - Provide a calm and supportive environment- Reassure and use effective communication techniques |

| 3. Symptom Management | - Administer benzodiazepines (eg, lorazepam, diazepam) for severe agitation or anxiety- Consider antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol) for severe hallucinations |

| 4. Fluid and Electrolyte Management | - Monitor fluid status and provide appropriate hydration- Correct electrolyte imbalances |

| 5. Psychological Support | - Engage in non-judgmental and supportive communication- Consider involving mental health professionals |

| 6. Observation and Monitoring | - Continuously monitor vital signs and mental status- Watch for potential complications (eg, hyperthermia; consider testing creatine kinase for rhabdomyolysis) |

| 7. Collaborative Care | - Consult toxicology specialists or medical toxicologists- Involve psychiatry or mental health services |

| 8. Discharge Planning | - Provide appropriate discharge instructions - Educate the patient about LSD risks and refer them for support |

Differential Diagnosis

Other drugs of abuse require consideration in the differential diagnosis of LSD intoxication, such as the following:

- 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

- 3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetmine (MDA)

- N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)

- Psilocybin

- Phencyclidine (PCP)

- Cocaine and other amphetamines

- Ethanol

- Benzodiazepines

- Barbiturates

- Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)

Psychiatric conditions, such as psychosis and schizophrenia, should be considered in the differential. Depending on the patient’s presentation, infections and tumors within the central nervous system should also be in the differential. Differentiate the altered mental status from LSD intoxication from other causes, such as electrolyte abnormalities.

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally favorable in patients presenting under the influence of LSD, provided the exclusion of other diagnoses, and no complications arise. Since treatment is primarily supportive, the expectation is for quality outcomes as long as the clinical staff follows the treatment recommendations provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Complications

Complications from LSD intoxication can arise in a few places. One is the environment in which the patient ingested the substance. If the scene is not safe, and the patient causes accidental harm to themselves or others, this can lead to a myriad of complications, such as trauma.

Persistent psychotic symptoms can manifest in those who ingest large doses of LSD. Patients often refer to their “trips” as life-altering experiences, and those who experience particularly profound departures from reality may have a difficult time adjusting long after the drug’s effects have worn off.

Hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder is a potential complication of hallucinogen intoxication. DSM-5 defines this condition as a disorder where patients not currently under the influence of a hallucinogenic agent experience perceptual symptoms initially manifested during prior hallucinogenic experiences. These symptoms must result in clinically significant distress and impair normal social and occupational functions. Reports have shown these symptoms to include mainly visual disturbances, such as geometric hallucinations, halos surrounding objects, alterations in motion perception, floaters, and flashbacks to images seen during the previous drug experience.[13] Autonomic complications arise when there is a failure to treat symptoms of hypertension, hypotension, arrhythmias, and hyperthermia.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education about the risks of LSD must be emphasized to reduce accidental ingestion and overdose. Patients often experiment without knowledge of the substances they ingest, and this understandably leads to many negative experiences and potentially unnecessary hospitalizations. Since LSD is a Schedule I substance, education about the ramifications of possessing and distributing such substances should also be emphasized, along with the substance’s mechanism of action and subjective effects.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients arriving at the emergency department with drug intoxication present unique challenges to the healthcare team. Since the differential diagnosis of LSD intoxication, let alone any drug intoxication, is an exhaustive list, an emphasis on obtaining a thorough history and physical exam is important. This process starts with EMTs and paramedics, physicians and nurses, and pharmacists preparing medications if applicable. The interprofessional team works together, providing optimal care to prevent fatal drug interactions.

Although LSD is one of the most well-known illegal drugs, numerous drug analogs have been designed to offer many of the same effects as the substances currently outlawed by the government, and healthcare workers may have insufficient knowledge. Education about current and past designer drugs may be of great benefit to those working in healthcare when the source of intoxication is under question or perceived to be unknown.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chemical Structure of LSD

This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Benjah-bmm27, Wikimedia Commons.

References

AGHAJANIAN GK, BING OH. PERSISTENCE OF LYSERGIC ACID DIETHYLAMIDE IN THE PLASMA OF HUMAN SUBJECTS. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 1964 Sep-Oct:5():611-4 [PubMed PMID: 14209776]

Nichols DE, Grob CS. Is LSD toxic? Forensic science international. 2018 Mar:284():141-145. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.01.006. Epub 2018 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 29408722]

Ortiz NR, Preuss CV. Controlled Substance Act. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34662058]

Sessa B. Can psychedelics have a role in psychiatry once again? The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2005 Jun:186():457-8 [PubMed PMID: 15928353]

Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, Cosimano MP, Klinedinst MA. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2016 Dec:30(12):1181-1197 [PubMed PMID: 27909165]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDe Gregorio D, Comai S, Posa L, Gobbi G. d-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) as a Model of Psychosis: Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016 Nov 23:17(11): [PubMed PMID: 27886063]

Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Steuer AE, Kraemer T, Rentsch KM, Hammann F, Liechti ME. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Subjects. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2017 Oct:56(10):1219-1230. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0513-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28197931]

Krebs TS, Johansen PØ. Over 30 million psychedelic users in the United States. F1000Research. 2013:2():98. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-98.v1. Epub 2013 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 24627778]

Rickert VI, Siqueira LM, Dale T, Wiemann CM. Prevalence and risk factors for LSD use among young women. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2003 Apr:16(2):67-75 [PubMed PMID: 12742139]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDolder PC, Liechti ME, Rentsch KM. Development and validation of a rapid turboflow LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of LSD and 2-oxo-3-hydroxy LSD in serum and urine samples of emergency toxicological cases. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2015 Feb:407(6):1577-84. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8388-1. Epub 2014 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 25542574]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerg T, Jørgenrud B, Strand DH. Determination of buprenorphine, fentanyl and LSD in whole blood by UPLC-MS-MS. Journal of analytical toxicology. 2013 Apr:37(3):159-65. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkt005. Epub 2013 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 23423312]

Williams JF, Lundahl LH. Focus on Adolescent Use of Club Drugs and "Other" Substances. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2019 Dec:66(6):1121-1134. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.08.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31679602]

Orsolini L, Papanti GD, De Berardis D, Guirguis A, Corkery JM, Schifano F. The "Endless Trip" among the NPS Users: Psychopathology and Psychopharmacology in the Hallucinogen-Persisting Perception Disorder. A Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2017:8():240. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00240. Epub 2017 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 29209235]