Introduction

The abducens nerve, the sixth cranial nerve (CN VI), is responsible for ipsilateral eye abduction. Dysfunction of the abducens nerve can occur at any point of its transit from the pons to the lateral rectus muscle, resulting in sixth nerve palsy.[1] To understand the causes of this palsy, it is essential to understand the nerve's anatomy as it transverses the brain.

The abducens nerve originates in the pons, near the seventh cranial nerve. It then exits the brainstem and enters the subarachnoid space, following a path along the skull called the clivus. Continuing its journey, the nerve reaches the petrous apex of the temporal bone in the basal skull, where it enters the cavernous sinus.[2]

Within the cavernous sinus, the abducens nerve is positioned medially to the internal carotid artery, while the trigeminal nerve is located laterally. After passing through the cavernous sinus, the abducens nerve enters the orbit via the superior orbital fissure. Once in the orbit, it innervates the lateral rectus muscle responsible for eye abduction.[3][4][5]

Sixth cranial nerve palsy is the most common isolated palsy in adults and the second most common cranial nerve palsy in children. When diagnosing a case of sixth nerve palsy, the patient's age plays a critical role in determining the underlying cause and the need for further evaluation, including neurological imaging.[6]

In adults, the risk factors for abducens nerve palsy can be categorized as vasculopathic or non-vasculopathic. Vasculopathic risk factors are more common in older patients and may include conditions such as diabetes. On the other hand, non-vasculopathic causes can be present in adults and children and may involve various factors such as trauma, inflammation, or compression.

The most common risk factors for sixth nerve palsy in children include increased intracranial pressure, vascular anomalies, and neoplastic disorders. It is important to note that in children, after ruling out trauma, idiopathic causes, and postviral etiologies, neurological imaging is necessary to investigate the underlying cause further.[7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

As mentioned previously, understanding the path of the abducens nerve is important in determining the etiology of abducens nerve palsy. Neoplasms and trauma can affect the abducens nerve at any point along its course and cause palsy. However, other causes of abducens nerve palsy can be categorized based on the location of the abducens nerve.[8][9][10]

Abducens nerve palsy can have nuclear and fascicular causes, which involve pathologies that directly affect the pons, where the nucleus and fascicles of the sixth nerve are located. Some examples of nuclear and fascicular causes include ischemic stroke, metabolic diseases such as Wernicke disease, and demyelinating lesions. These nuclear causes may be associated with facial nerve palsies due to the proximity of abducens and facial nerves in the pons.[11]

Additional etiologies may arise as the abducens nerve enters the subarachnoid space, leading to abducens nerve palsy. In these cases, the palsy is primarily caused by increased intracranial pressure. Other accompanying symptoms, such as headache, nausea, vomiting, and papilledema, may be observed. Several causes can contribute to abducens nerve palsy in this context. These include an aneurysm, carcinomatous meningitis, procedure-related injury (eg, spinal anesthesia, postlumbar puncture), inflammatory lesions (eg, sarcoid, lupus), and infection (eg, Lyme disease, syphilis, tuberculosis, Cryptococcus).[12]

Since the abducens nerve courses over the petrous apex, there are specific causes of abducens nerve palsy associated with this region. These causes include complicated otitis media or mastoiditis, sinus thrombosis, and basal skull fracture.[13]

As the abducens nerve traverses the cavernous sinus, the most common cause of palsy in this region is stretching or compression of the abducens nerve. These etiologies include cavernous sinus thrombosis, cavernous sinus fistula, and internal carotid aneurysm or dissection.[14]

Lastly, orbital lesions can also cause an abducens nerve palsy. These conditions include neoplasm, inflammatory disease, infection, or trauma.[15]

Table 1. Etiology of Sixth Nerve Palsy in Children

|

S. No |

Etiology |

Examples |

|

1 |

Idiopathic |

|

|

2 |

Trauma |

Traumatic brain injury Basal skull fracture |

|

3 |

Tumor |

Benign Malignant Metastasis |

|

4 |

Iatrogenic |

Birth injury Vaccine-induced trauma Neurological injury |

|

5 |

Neurological Pathologies |

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension Migraine Multiple sclerosis |

|

6 |

Infections |

Brain abscess Herpes zoster virus Epstein-Barr virus Meningitis Cytomegalo virus Gradenigo syndrome Lyme Disease |

|

7 |

Vaculopathic disorders |

Diabetes Hypertension Atherosclerosis |

|

8 |

Miscellaneous |

Intracranial aneurysms Arteriovenous malformation Arnold-Chiari malformation Hydrocephalus |

Table 2. Etiology of Sixth Nerve Palsy in Adults

|

S. No |

Etiology |

Example |

|

1 |

Vasculopathic |

Diabetes Hypertension Atherosclerosis |

|

2 |

Traumatic |

Basal skull fracture Head trauma Spinal fracture |

|

3 |

Tumur |

Benign Metastatic Malignant |

|

4 |

Infectious |

Fungal infection Bacterial infections Syphilis Herpes zoster Lymes disease |

|

5 |

Hematologic |

Leukaemia Lymphoma Interferon therapy |

|

6 |

Neurological pathologies |

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension Multiple sclerosis Cluster headache Lithium toxicity |

|

7 |

Systemic disorders |

Systemic lupus erythematosus Collagen vascular disorders Sarcoidosis Amyloidosis |

|

8 |

Vascular intracranial pathologies |

Aneurysms Arteriovenous malformations Giant cell arteritis Carotid artery dissection |

|

9 |

Iatrogenic |

Neurosurgical trauma Nerve block Lumbar puncture Myelography Spinal anesthesia |

Syndromes Associated with Sixth Cranial Nerve Palsy

- Brainstem syndromes

- Elevated intracranial pressure

- Petrous apex syndrome

- Cavernous sinus syndrome

- Orbital syndrome [2]

Brainstem Syndromes

- Raymond syndrome is characterized by abducens nerve palsy and contralateral hemiplegia (pyramidal tract involvement).[16]

- Millard-Gubler syndrome: In this syndrome, abducens nerve palsy (CN 6 involvement), ipsilateral facial nerve palsy (CN 7 involvement), and contralateral hemiplegia (pyramidal tract involvement) are observed.[17]

- Foville syndrome: This syndrome presents with abducens nerve palsy (CN 6), horizontal conjugate gaze paresis, ipsilateral Horner's syndrome and ipsilateral involvement of trigeminal (CN5), facial (CN 7), vestibulocochlear (CN 8).[18]

Elevated Intracranial Pressure

The change in intraocular pressure can cause downward herniation of the brainstem, resulting in stretching or compression of the sixth nerve. The abducens nerve is located near the pons and Dorello's canal, making it susceptible to such effects.

In patients with pseudotumor cerebri, abducens nerve palsy can occur along with other symptoms, such as papilledema and visual field defects, resulting in blind spot enlargement.

Other pathologies associated with elevated cranial pressure are subarachnoid hemorrhage, infection of the meninges (viral, bacterial, or fungal), inflammatory conditions (sarcoidosis), or infiltrative causes such as lymphoma, leukemia, and carcinoma.[19]

Petrous Apex Syndrome

- Gradenigo Syndrome: Also known as Gradenigo's Triad, this is a rare condition characterized by a combination of symptoms that include Abducens nerve palsy, Facial nerve (CN 7) involvement causing reduced hearing, ipsilateral facial pain along the trigeminal nerve (CN 5) distribution and ipsilateral facial paresis (due to CN 7). Tumors in the cerebellopontine angle, such as acoustic neuromas and meningiomas, can also affect the sixth cranial nerve and other nearby cranial nerves, resulting in hearing loss and decreased corneal sensitivity. This can sometimes be mistaken for petrous apex syndrome.[20]

- Pseudo-Gradenigo Syndrome: This condition presents with hearing loss, sixth nerve palsy, and trigeminal symptoms. It is typically caused by brainstem lesions such as cerebellopontine angle tumors. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma may also mimic Gradenigo's syndrome as it blocks the Eustachian tube.[21]

Cavernous Sinus Syndrome

- Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: This carcinoma may cause sixth nerve palsy, typically occurring between the fourth and seventh decades. Symptoms may include nasal obstruction, rhinorrhoea, epistaxis, and serous otitis media.[22]

- Intracavernous internal carotid artery aneurysm: Aneurysms in the cavernous sinus can involve the sixth and the third cranial nerves, which are most vulnerable in this location. However, the proportion of aneurysms causing palsy is very small, approximately 3%.[23]

- Carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF): CCF refers to an abnormal connection between the internal carotid artery and the cavernous sinus. This condition can result in arterialization of the sinus and ocular and orbital veins leading to symptoms such as pain, congestion, chemosis, proptosis, ocular pulsation, and double vision.[24]

- Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: This idiopathic sterile inflammation affects the anterior portion of the cavernous sinus and causes sixth nerve palsy.[25]

Meningioma

Meningiomas along the sphenoid ridge, anterior clinoid, or tuberculum sellae can be associated with sixth nerve palsy. In addition to this palsy, these meningiomas may cause exophthalmos, bitemporal hemianopia, monocular blindness, and upper temporal junctional scotoma.[2]

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous causes can lead to an abducens nerve palsy, such as metastatic lesions, neurofibromatosis, syphilis, herpes zoster, multiple myeloma, craniopharyngioma, and lymphoma.

Orbital Syndrome Involving Sixth Nerve Palsy

Patients experiencing orbital syndrome with sixth nerve palsy exhibit various symptoms, including proptosis, conjunctival chemosis, optic atrophy, and papilledema. Horner syndrome may also manifest in these cases, while ptosis might go unnoticed due to the masking effect of proptosis. Other tumors that can present with similar symptoms are orbital tumors, pseudotumors, thyroid eye disease, orbital cellulitis, and myositis.[26]

Isolated Sixth Nerve Palsy Syndrome

Isolated sixth nerve palsy can arise from various factors, including diabetes, hypertension, and recent viral infections. The isolated involvement can also be recurrent. Ophthalmic migraine can also cause abducens nerve palsy, and the involvement can be either central or peripheral. When imaging results reveal mixed findings, determining the specific type of palsy becomes challenging. Immunologic damage to the sixth nerve can occur at any point.[2]

Epidemiology

The sixth cranial nerve is the most commonly affected ocular motor nerve in adults. In children, it is the second most common, following the fourth cranial nerve, with an incidence of 2.5 cases per 100,000. Poorly controlled diabetes is a significant risk factor for developing abducens nerve palsy.[9]

A study of the Korean population revealed an overall incidence rate of 4.66 cases of sixth cranial nerve palsy per 100,000 individuals per year within the patient population. The incidence of this condition demonstrated an upward trend with advancing age. The incidence significantly increased at 60, reaching its peak between 70 and 74.[27]

The incidence rates of sixth cranial nerve palsy vary depending on the underlying cause. The reported incidence ranges are as follows: traumatic causes for 3% to 30%, aneurysms for up to 6%, demyelination or miscellaneous factors for 10% to 30%, idiopathic cases for 8% to 30%, ischemic causes for up to 36%.

A 15-year study in the United States, involving 137 cases, reported an age- and gender-adjusted incidence rate of sixth nerve palsy to be 11.3 per 100,000. The study found that the peak incidence occurred in the seventh decade of life. Among the cases, there were 4 cases of bilateral sixth nerve palsy and 16 cases of multiple cranial nerve palsy.[27]

Pathophysiology

The abducens nerve supplies the ipsilateral lateral rectus, which is responsible for horizontal eye movement. Consequently, when the sixth cranial nerve is affected, deviations occur only in the horizontal plane. In cases where only the isolated peripheral nerve is involved, no vertical or torsional movements are present.[28]

The abducens nerve is primarily responsible for ipsilateral eye abduction. When abducens nerve palsy occurs, the affected nerve cannot transmit signals to the lateral rectus muscle, resulting in an inability to abduct the eye and subsequent horizontal diplopia. In cases involving central nervous system defects, the sixth nerve tract can be localized based on characteristic findings associated with each type of lesion.[29]

Involvement of the sixth nerve nucleus causes ipsilateral gaze palsy. The absence of contralateral adduction helps distinguish a nuclear lesion from a fascicular or nonnuclear lesion. When intracranial pressure is elevated, and the sixth nerve is stretched, a false localizing sign can occur, indicating abducens nerve palsy as the nerve crosses the clivus.

Abducens nerve palsy can also result from post-viral syndrome in the pediatric and adolescent populations, while in adults, it can present as ischemic mononeuropathy.[30]

History and Physical

Patients who develop abducens nerve palsy often present with binocular horizontal diplopia, which refers to double vision when viewing objects side by side. This is due to a notable weakness in the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle, resulting in an inability to abduct the affected side.[31] Some patients may present with a constant head-turning movement to maintain binocular fusion and reduce the degree of diplopia.[32] The diplopia is more pronounced when looking into the distance or during lateral gaze.

Additional clinical history findings may include vision loss, headache, vomiting, trauma, hearing loss, recent lumbar puncture, or recent viral illness. Patients may also present with esotropia, head turn, facial pain, or numbness. Some patients may have underlying conditions such as giant cell arteritis, sharp shooting temporal headache, and facial pain. All patients presenting with these symptoms need a detailed ophthalmological examination.[33]

When assessing a patient with abducens nerve palsy, a comprehensive evaluation should be conducted, including the following:[34]

- Visual acuity evaluation

- Binocular single vision

- Stereopsis

- Ocular movement assessment

- Squint evaluation

- Measurements at near and distance

- Cardinal positions of gaze

- Assessment of fusional amplitude

- Manifest and cycloplegic refraction

- Anterior and posterior segment evaluation

Measuring ocular movements during lateral gaze and assessing duction and ocular versions are valuable for identifying incomitance associated with abducens nerve palsy.

Patients with sixth nerve palsy have slow saccadic velocity in side gaze, which helps diagnose.

In pediatric patients, tumors and trauma are the most common etiologies of sixth nerve palsy. Therefore, a thorough and careful evaluation must be performed to rule out serious etiologies. It is imperative to consider the pseudo-restrictive effects of alternating monocular fixation and vergence, as assessing both eyes simultaneously may lead to misleading results. Thus, independent evaluation of each eye is essential.[35]

Diplopia is the most common symptom in patients with abducens nerve palsy. The characteristic diplopia experienced is horizontal and uncrossed, primarily affecting distant vision rather than near vision. The diplopia is more pronounced in the direction of the affected muscle and improves with a contralateral gaze. In acute onset sixth nerve palsy cases, the deviation is more prominent when the paretic muscle is fixating compared to the nonparetic muscle. This follows Hering’s law of primary and secondary deviations.[31]

The other symptoms accompanying sixth nerve palsy depend on the underlying etiology—patients with raised intracranial pressure present with headache, ocular pain, nausea, vomiting, and tinnitus. Conversely, low intracranial pressure due to CSF leak can also lead to abducent nerve palsy, accompanied by headache, mimicking the symptoms of raised ICP. Patients with a neurological etiology present with neurological signs and symptoms. For example, those with subarachnoid hemorrhage can exhibit leptomeningeal irritation and a feature of cranial nerve palsy.[36]

When the cause of sixth nerve palsy involves the brainstem and affects the sixth nerve fasciculus, it can lead to ipsilateral facial weakness, sensory involvement, and contralateral hemiparesis (Millard-Gubler syndrome). In the event of multiple cranial nerve palsy, the lesion can be localized to various anatomical sites, including the meninges, orbital apex, superior orbital fissure, and cavernous sinus.

Evaluation

The sixth cranial nerve palsy diagnostic workup depends on the suspected underlying cause. A thorough evaluation should be conducted in cases involving children, as there is a significantly higher risk of neoplastic causes. Neuroimaging should be performed promptly at the time of injury in the setting of abducens nerve palsy associated with trauma. A lumbar puncture should be performed if elevated intracranial pressure is suspected as the cause. When an ischemic etiology is suspected palsy is suspected, MRI is recommended as the preferred modality because of its superior capability of imaging the posterior fossa.[37][38]

MRI is indicated in patients younger than 50 without vasculopathy, mainly when there is a history of associated pain or neurological abnormalities, as well as with patients with a history of carcinomas, bilateral abducent nerve involvement, or papilledema. If the palsy doesn't improve within 3 to 4 months or when other cranial nerves are involved, a detailed medical, neurological, and imaging workup should be conducted for microvascular ischemic sixth nerve palsy.[39]

Laboratory Studies

In the workup of sixth cranial nerve palsy, the following laboratory studies may be considered:

- Complete blood cell count: Assessing for any abnormalities

- Diabetes profile: Includes fasting glucose, 2-hour postprandial glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C), and glucose tolerance test.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation: Measuring for inflammation.

- C-reactive protein: Testing to assess for possible giant cell arteritis.

- Platelet count: Evaluation for thrombocytopenia in elderly patients.

- Acetylcholine receptor antibodies: Considered if myasthenia gravis is suspected.

- Rapid plasma reagin test: Screening for syphilis infection.

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test: Used to confirm syphilis diagnosis if there is a suspicion.

- Lyme titer: Testing for suspected Lyme disease.

- Thyroid function tests: Assessing thyroid hormone levels

- Antinuclear antibody test: Detecting autoantibodies associated with various autoimmune conditions.

- Rheumatoid factor test: Checking for possible underlying rheumatoid arthritis.

Other Tests

Several factors should be considered and assessed when evaluating a patient with sixth cranial nerve palsy. It is essential to examine the patient's blood pressure for any abnormalities or signs of hypertension, as specific causes of sixth nerve palsy can be associated with vascular conditions. A thorough history should be obtained, and attention paid to recent trauma, ocular infections, transient loss of vision, and fluctuating symptoms. The other cranial nerve should be examined in detail to identify any additional neurological abnormalities.

Higher mental functions should be assessed along with sensory and motor examination. A detailed otoscopic examination should be mandated in pediatric patients to rule out complicated otitis media.

Treatment / Management

The management of sixth nerve palsy depends on the underlying etiology. The initial focus should be addressing any uncontrolled systemic pathology in the patient. For most patients, sixth nerve palsy resolves spontaneously without requiring systemic treatment. However, in children, treatment approaches may be considered.

Treatment options for children with sixth nerve palsy include alternate patching, prism therapy, strabismus surgery, and botulism toxin injections. Alternate patching involves patching each eye alternatively for a few hours each day.[40] This approach is used to prevent amblyopia in the affected eye. Prism therapy requires placing a temporary press-on prism on the lens of the affected eye to help align the visual axes. Children who do not show improvement with prism therapy would be eligible for strabismus surgery to correct the misalignment. Botulinum toxin injections can sometimes be administered into the medial rectus muscle of the affected eye to prevent contracture and nasal deviation.[41][42][43](A1)

Using Bangerter filters or patches also helps eliminate diplopia and confusion and prevents amblyopia in children. These filters or patches can also reduce the possibility of ipsilateral medial rectus contracture. Additionally, Fresnel prisms can help patients maintain single binocular vision in the primary position when placed in a base-out position.[44](B3)

In most cases of microvascular sixth nerve palsy, no intervention is required, and the condition resolves spontaneously with observation alone. It takes nearly 3 to 6 months for the symptoms to resolve independently. However, the underlying cause of the abducens nerve palsy will dictate the specific treatment approach.

For example, if the cause is temporal arteritis, steroid medications may be prescribed as part of the treatment plan. When the cause is related to intracranial pressure, such as pseudotumor cerebri and cancer, the pressure must be reduced through surgical intervention or by performing a lumbar puncture.

Treatment of persistent sixth nerve palsy that does not resolve spontaneously would be similar to those used in children. However, alternative patching has not proven effective in adults.[45]

Surgical treatment for sixth nerve palsy is reserved for patients with stable orthoptic status for at least 6 months. Before undergoing any surgical intervention, every patient should undergo a forced duction test for meticulous surgery planning.[46] Once the stability of the orthoptic status has been established and the forced duction test has been conducted, the appropriate surgical procedure can be planned.

The surgical technique employed will depend on the underlying cause of the sixth nerve palsy and the patient's condition. Surgical options may include muscle transposition procedures, muscle recessions, or other corrective techniques to address the imbalance of ocular muscle function.

- The Resect and Recess procedure is a surgical approach performed for patients with residual lateral rectus function in cases of sixth nerve palsy. This procedure involves resecting the lateral rectus muscle on the affected side and recessing the same side medial rectus muscle. Alternatively, the procedure can be modified by resecting the lateral rectus muscle and recessing the medial rectus muscle on the affected side.[47]

- If the lateral rectus function is absent, transposition surgeries can be considered an alternative surgical approach. These procedures include tendon transposition, Jensen procedure, Hummelsheim procedure, Augmented Hummelsheim with resection and with or without Foster modifications, and Knapp procedure. Superior rectus transposition, combined with medical rectus recession, has improved esotropia, head positions, and abduction in patients with abducens palsy.[48] (B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for abducens nerve palsy is extensive and includes the following:

- Myasthenia gravis

- Type 1 and 3 Duane retraction syndrome (DRS) in children [49]

- Thyroid eye disease

- Syphilis [50]

- Pseudotumor cerebri

- Spasm of the near reflex

- Orbital medial wall fractures

- Lyme disease

- Trauma [51][52][53][54]

- Neoplasm

- Delayed break in the fusion

- Old blowout fracture

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Aneurysms

- Vasculopathy

- Congenital esotropia [55][56]

- Sphenoiditis

- Lateral rectus myositis

- Chronic suppurative otitis media

- Miller-Fisher syndrome

- Neoplasms

- Neuromyotonia

In DRS, a palpebral fissure narrowing occurs upon adduction of the affected eye. However, there is no narrowing in sixth nerve palsy, differentiating the 2 conditions. Patients with thyroid eye disease may present with bilateral involvement, although unilateral involvement can occur, with symptoms such as proptosis and inflamed conjunctiva. In myasthenia gravis, symptoms include fluctuating diplopia along with fatigue, shortness of breath, and hoarseness.

Prognosis

The prognosis of abducens nerve palsy varies depending on the underlying cause. When caused by a viral illness, complete remission is commonly observed. However, residual symptoms may persist when the palsy is secondary to trauma. The most significant improvement is typically seen in the first 6 months. Most patients who experience idiopathic sixth cranial nerve palsy recover completely, although a few individuals may experience permanent vision changes.[2]

Complications

Complications associated with abducens nerve palsy vary based on the underlying etiology. The most common complication following surgical correction is the potential of over- or under-correction. Such complications can be effectively managed postoperatively using prisms to achieve optimal alignment.

A list of complications following surgical correction are as follows:

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Regular follow-up is essential for all patients who have undergone surgical correction of strabismus. Postoperative medication should be continued in tapering doses as prescribed. Patients should be educated about the importance of regular and timely usage of topical steroids and lubricants. They should also be informed about the potential occurrence of postoperative diplopia and how it can be managed using prisms.[59]

Consultations

All patients displaying signs of sixth nerve palsy should undergo a thorough evaluation by a pediatric ophthalmologist, strabismologist, and neurologist. This comprehensive evaluation aims to accurately diagnose and determine the underlying cause of the sixth nerve palsy.[40]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed about the possibility of the self-limiting nature of the condition and may be advised to undergo an observation period of about 6 months. Surgical correction can be offered if the patient fails to show any improvement during this time. Of course, a known underlying condition must be addressed first, and patient counsel will primarily focus on that issue.[60]

Pearls and Other Issues

Abducens nerve palsy is a condition that requires careful consideration of the underlying pathology responsible for the observed lateral rectus paresis. The process involves employing a systematic differential diagnosis approach that follows the anatomical pathways of the nerve to determine the underlying cause. Once the cause is identified, treatment can be targeted toward addressing the underlying condition.[15]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Abducens nerve palsy is a frequently encountered condition characterized by horizontal diplopia. However, accompanying symptoms may vary depending on the underlying cause. Due to the numerous etiologies associated with this condition, a collaborative approach involving multiple healthcare professionals is essential for effective management. The team typically includes a neurologist, ophthalmologist, neurosurgeon, and radiologist. Additionally, an ophthalmology specialty-trained nurse should assist with surgical interventions and educate patients about the condition and its treatment. When a patient presents with horizontal diplopia, prompt referral to a neurologist should be made by the nurse practitioner or primary care provider. The underlying cause determines the prognosis and outcome of abducens nerve palsy.[61][62]

Media

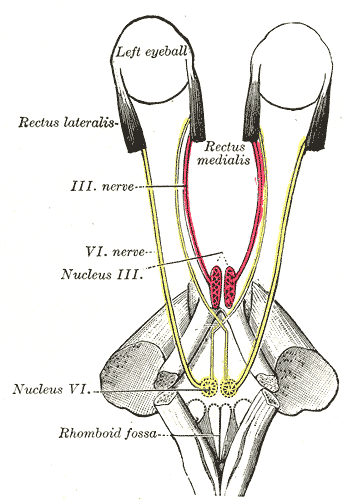

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Abducens Nerve. The mode of innervation of the Recti medialis and lateralis of the eye, rhomboid fossa, and rectus medialis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Nguyen V, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 6 (Abducens). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613463]

Azarmina M, Azarmina H. The six syndromes of the sixth cranial nerve. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2013 Apr:8(2):160-71 [PubMed PMID: 23943691]

Parr M, Carminucci A, Al-Mufti F, Roychowdhury S, Gupta G. Isolated Abducens Nerve Palsy Associated with Ruptured Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Aneurysm: Rare Neurologic Finding. World neurosurgery. 2019 Jan:121():97-99. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.096. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30266698]

Ibekwe E, Horsley NB, Jiang L, Achenjang NS, Anudu A, Akhtar Z, Chornenka KG, Monohan GP, Chornenkyy YG. Abducens Nerve Palsy as Initial Presentation of Multiple Myeloma and Intracranial Plasmacytoma. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Sep 3:7(9):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090253. Epub 2018 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 30177596]

Khan Z, Bollu PC. Horner Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763176]

Nair AG, Ambika S, Noronha VO, Gandhi RA. The diagnostic yield of neuroimaging in sixth nerve palsy--Sankara Nethralaya Abducens Palsy Study (SNAPS): Report 1. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Oct:62(10):1008-12. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.146000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25449936]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSolanki JD, Makwana AH, Mehta HB, Gokhale PA, Shah CJ. A Study of Prevalence and Association of Risk Factors for Diabetic Vasculopathy in an Urban Area of Gujarat. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2013 Oct-Dec:2(4):360-4. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.123906. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26664842]

Kim JH, Hwang JM. Imaging of Cranial Nerves III, IV, VI in Congenital Cranial Dysinnervation Disorders. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2017 Jun:31(3):183-193. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0024. Epub 2017 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 28534340]

Hofer JE, Scavone BM. Cranial nerve VI palsy after dural-arachnoid puncture. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2015 Mar:120(3):644-646. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000587. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25695579]

Lyons CJ, Godoy F, ALQahtani E. Cranial nerve palsies in childhood. Eye (London, England). 2015 Feb:29(2):246-51. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.292. Epub 2015 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 25572578]

Reese V, Das JM, Al Khalili Y. Cranial Nerve Testing. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36251851]

Costa JV, João M, Guimarães S. Bilateral papilledema and abducens nerve palsy following cerebral venous sinus thrombosis due to Gradenigo's syndrome in a pediatric patient. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2020 Sep:19():100824. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100824. Epub 2020 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 32695930]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChoi KY, Park SK. Petrositis With Bilateral Abducens Nerve Palsies complicated by Acute Otitis Media. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology. 2014 Mar:7(1):59-62. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2014.7.1.59. Epub 2014 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 24587883]

Plewa MC, Tadi P, Gupta M. Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846357]

Erdal Y, Gunes T, Emre U. Isolated abducens nerve palsy: Comparison of microvascular and other causes. Northern clinics of Istanbul. 2022:9(4):353-357. doi: 10.14744/nci.2021.15483. Epub 2022 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 36276565]

Silverman IE, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL. The crossed paralyses. The original brain-stem syndromes of Millard-Gubler, Foville, Weber, and Raymond-Cestan. Archives of neurology. 1995 Jun:52(6):635-8 [PubMed PMID: 7763214]

Sakuru R, Elnahry AG, Lui F, Bollu PC. Millard-Gubler Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422502]

Massi DG, Nyassinde J, Ndiaye MM. Superior Foville syndrome due to pontine hemorrhage: a case report. The Pan African medical journal. 2016:25():215. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.25.215.10648. Epub 2016 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 28292169]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePinto VL, Tadi P, Adeyinka A. Increased Intracranial Pressure. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489250]

Tornabene S, Vilke GM. Gradenigo's syndrome. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2010 May:38(4):449-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.08.074. Epub 2008 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 18296009]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDemir B, Abuzaid G, Ergenc Z, Kepenekli E. Delayed diagnosed Gradenigo's syndrome associated with acute otitis media. SAGE open medical case reports. 2020:8():2050313X20966119. doi: 10.1177/2050313X20966119. Epub 2020 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 33194201]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBatawi H, Micieli JA. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma presenting as a sixth nerve palsy and Horner's syndrome. BMJ case reports. 2019 Oct 10:12(10):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-232291. Epub 2019 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 31604725]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlmaghrabi N, Fatani Y, Saab A. Cavernous internal carotid artery aneurysm presenting with ipsilateral oculomotor nerve palsy: A case report. Radiology case reports. 2021 Jun:16(6):1339-1342. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.03.008. Epub 2021 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 33897925]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEllis JA, Goldstein H, Connolly ES Jr, Meyers PM. Carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurgical focus. 2012 May:32(5):E9. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.FOCUS1223. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22537135]

Dutta P, Anand K. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome: A Review of Diagnostic Criteria and Unresolved Issues. Journal of current ophthalmology. 2021 Apr-Jun:33(2):104-111. doi: 10.4103/joco.joco_134_20. Epub 2021 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 34409218]

Fischer M, Kempkes U, Haage P, Isenmann S. Recurrent orbital myositis mimicking sixth nerve palsy: diagnosis with MR imaging. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2010 Feb:31(2):275-6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1751. Epub 2009 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 19778999]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJung EH, Kim SJ, Lee JY, Cho BJ. The incidence and etiology of sixth cranial nerve palsy in Koreans: A 10-year nationwide cohort study. Scientific reports. 2019 Dec 5:9(1):18419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54975-5. Epub 2019 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 31804597]

Clark RA, Demer JL. Lateral rectus superior compartment palsy. American journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Feb:157(2):479-487.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.027. Epub 2013 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 24315033]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWalker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW. Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI: The Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Abducens Nerves. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990:(): [PubMed PMID: 21250247]

Larner AJ. False localising signs. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2003 Apr:74(4):415-8 [PubMed PMID: 12640051]

Iliescu DA, Timaru CM, Alexe N, Gosav E, De Simone A, Batras M, Stefan C. Management of diplopia. Romanian journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Jul-Sep:61(3):166-170 [PubMed PMID: 29450393]

Gowda SN, Munakomi S, De Jesus O. Brainstem Stroke. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809731]

Kumar N, Kaur S, Raj S, Lal V, Sukhija J. Causes and Outcomes of Patients Presenting with Diplopia: A Hospital-based Study. Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press). 2021:45(4):238-245. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2020.1860091. Epub 2021 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 34366511]

Erkan Turan K, Kansu T. Acute Acquired Comitant Esotropia in Adults: Is It Neurologic or Not? Journal of ophthalmology. 2016:2016():2856128. doi: 10.1155/2016/2856128. Epub 2016 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 28018672]

Kekunnaya R, Negalur M. Duane retraction syndrome: causes, effects and management strategies. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2017:11():1917-1930. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S127481. Epub 2017 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 29133973]

Kesserwani H. Isolated Sixth Nerve Palsy: A Case of Pseudotumor Cerebri and an Overview of the Evolutionary Dynamic Geometry of Dorello's Canal. Cureus. 2021 May:13(5):e15340. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15340. Epub 2021 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 34235019]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChi SL, Bhatti MT. The diagnostic dilemma of neuro-imaging in acute isolated sixth nerve palsy. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2009 Nov:20(6):423-9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283313c2f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19696672]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarlow TJ. Paresis of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI: clinical manifestation and differential diagnosis. Bulletin de la Societe belge d'ophtalmologie. 1989:237():285-301 [PubMed PMID: 2486113]

Lekskul A, Thanomteeranant S, Tangtammaruk P, Wuthisiri W. Isolated Sixth Nerve Palsy as a First Presentation of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Case Series. International medical case reports journal. 2021:14():801-808. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S334476. Epub 2021 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 34849037]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMerino P, Gómez de Liaño P, Villalobo JM, Franco G, Gómez de Liaño R. Etiology and treatment of pediatric sixth nerve palsy. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2010 Dec:14(6):502-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.09.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21168073]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceToda M, Kosugi K, Ozawa H, Ogawa K, Yoshida K. Surgical Treatment of Cavernous Sinus Lesion in Patients with Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas via the Endoscopic Endonasal Approach. Journal of neurological surgery. Part B, Skull base. 2018 Oct:79(Suppl 4):S311-S315. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667123. Epub 2018 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 30210983]

Sabermoghadam A, Etezad Razavi M, Sharifi M, Kiarudi MY, Ghafarian S. A modified vertical muscle transposition for the treatment of large-angle esotropia due to sixth nerve palsy. Strabismus. 2018 Sep:26(3):145-149. doi: 10.1080/09273972.2018.1492621. Epub 2018 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 29985743]

Rowe FJ, Hanna K, Evans JR, Noonan CP, Garcia-Finana M, Dodridge CS, Howard C, Jarvis KA, MacDiarmid SL, Maan T, North L, Rodgers H. Interventions for eye movement disorders due to acquired brain injury. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Mar 5:3(3):CD011290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011290.pub2. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29505103]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKeskin ES, Keskin E, Atik B, Koçer A. A case of isolated abducens nerve paralysis in maxillofacial trauma. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Jul-Dec:5(2):258-61. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.175752. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26981484]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGaltrey CM, Schon F, Nitkunan A. Microvascular Non-Arteritic Ocular Motor Nerve Palsies-What We Know and How Should We Treat? Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press). 2015 Feb:39(1):1-11 [PubMed PMID: 27928323]

Bagheri A, Babsharif B, Abrishami M, Salour H, Aletaha M. Outcomes of surgical and non-surgical treatment for sixth nerve palsy. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2010 Jan:5(1):32-7 [PubMed PMID: 22737324]

Saleem QA, Cheema AM, Tahir MA, Dahri AR, Sabir TM, Niazi JH. Outcome of unilateral lateral rectus recession and medial rectus resection in primary exotropia. BMC research notes. 2013 Jul 8:6():257. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-257. Epub 2013 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 23834953]

Couser NL, Lenhart PD, Hutchinson AK. Augmented Hummelsheim procedure to treat complete abducens nerve palsy. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2012 Aug:16(4):331-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.02.015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22929448]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKaur K, Gurnani B. Exotropia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35201713]

Balamurugan S, Gurnani B, Kaur K. Commentry: Ocular coinfections in human immunodeficiency virus infection-What is so different? Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Sep:68(9):1997-1998. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_680_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32823456]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohseni M, Blair K, Gurnani B, Bragg BN. Blunt Eye Trauma. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261988]

Gurnani B, Kaur K, Venugopal A, Srinivasan B, Bagga B, Iyer G, Christy J, Prajna L, Vanathi M, Garg P, Narayana S, Agarwal S, Sahu S. Pythium insidiosum keratitis - A review. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Apr:70(4):1107-1120. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1534_21. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35325996]

Gurnani B, Kaur K, Gireesh P. A rare presentation of anterior dislocation of calcified capsular bag in a spontaneously absorbed cataractous eye. Oman journal of ophthalmology. 2021 May-Aug:14(2):120-121. doi: 10.4103/ojo.OJO_65_2019. Epub 2021 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 34345149]

Balamurugan S, Gurnani B, Kaur K, Gireesh P, Narayana S. Traumatic intralenticular abscess-What is so different? The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2020 Jan-Mar:30(1):92-94. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_369_19. Epub 2020 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 32476758]

Kaur K, Gurnani B. Esotropia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35201735]

Kaur K, Gurnani B, Nayak S, Deori N, Kaur S, Jethani J, Singh D, Agarkar S, Hussaindeen JR, Sukhija J, Mishra D. Digital Eye Strain- A Comprehensive Review. Ophthalmology and therapy. 2022 Oct:11(5):1655-1680. doi: 10.1007/s40123-022-00540-9. Epub 2022 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 35809192]

Gurnani B, Srinivasan K, Venkatesh R, Kaur K. Do motivational cards really benefit sibling screening of primary open-angle glaucoma probands? Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Dec:70(12):4158-4163. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1346_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36453305]

Singh K, Bhushan P, Mishra D, Kaur K, Gurnani B, Singh A, Pandey S. Assessment of optic disk by disk damage likelihood scale staging using slit-lamp biomicroscopy and optical coherence tomography in diagnosing primary open-angle glaucoma. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Dec:70(12):4152-4157. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1113_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36453304]

Nihalani BR, Hunter DG. Adjustable suture strabismus surgery. Eye (London, England). 2011 Oct:25(10):1262-76. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.167. Epub 2011 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 21760626]

Masic I, Miokovic M, Muhamedagic B. Evidence based medicine - new approaches and challenges. Acta informatica medica : AIM : journal of the Society for Medical Informatics of Bosnia & Herzegovina : casopis Drustva za medicinsku informatiku BiH. 2008:16(4):219-25. doi: 10.5455/aim.2008.16.219-225. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24109156]

Kim K, Noh SR, Kang MS, Jin KH. Clinical Course and Prognostic Factors of Acquired Third, Fourth, and Sixth Cranial Nerve Palsy in Korean Patients. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2018 Jun:32(3):221-227. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0051. Epub 2018 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 29770635]

Kumar K, Ahmed R, Bajantri B, Singh A, Abbas H, Dejesus E, Khan RR, Niazi M, Chilimuri S. Tumors Presenting as Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies. Case reports in neurology. 2017 Jan-Apr:9(1):54-61. doi: 10.1159/000456538. Epub 2017 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 28553221]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence