Introduction

Diarrhea is a common term used to describe loose/watery stools which occur three or more times within 24 hours.[1] For diarrhea to be considered chronic, symptoms must be ongoing for four or more weeks.[2] Virtually all patients will experience diarrhea at some point in time, and the definition of diarrhea will vary from patient to patient. It is essential for the physician to obtain specific information as to the precise nature of the patient’s symptoms to establish a definite diagnosis of diarrhea. Most patients will use the term diarrhea to describe loose or watery stools, regardless of the frequency.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact etiology of chronic diarrhea is quite broad as there are many different causes. Any process which causes increased water into the stool can produce diarrhea. These typically categorize into inflammatory and secretory diarrhea. The prevalence of the different causes will vary depending on the socioeconomic status of the individual. Individuals in a lower socioeconomic status will be more likely to have chronic bacterial, mycobacterial, and parasitic infections causing, whereas mid to high socioeconomic status individuals with chronic diarrhea are more likely to be afflicted with irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and malabsorption syndromes.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

This is defined as chronically abnormal bowel habits (diarrhea and/or constipation) associated with abdominal pain in the absence of any pathology. Females are more likely to be diagnosed with IBS than males. Symptoms of IBS are usually worsened by stress. The symptoms are generally described as crampy lower abdominal pain with associated diarrhea, constipation, or alternating diarrhea and constipation. Symptoms are often alleviated by defecation, although this is not necessary for diagnosis. For patients with diarrhea, they usually describe their bowel movements as being small or moderate amounts of loose stool. Usually, the bowel movements are associated with urgency.[3]

Medications

Certain medications are known to induce diarrhea in patients. Currently, there are greater than 700 drugs which are associated with diarrhea. Medical practitioners must look to the addition of new medications which may be associated with diarrhea. When the offending agent is discontinued, diarrhea may stop within as little as a day but may take longer if there is an injury to the intestinal mucosa. Patients who are receiving chemotherapy can have diffuse or segmental colitis. [4] Olmesartan producing a sprue-like enteropathy was first described in 2012. In this disease state, the intestinal mucosa will mimic the findings of celiac sprue, but the patients are not actually insensitive to gluten.[5]

Crohn Disease

Crohn disease is one of the inflammatory bowel diseases which is an autoimmune disease.[6] Typical symptoms include diarrhea (often associated with blood and/or mucus), abdominal pain, and signs of bowel obstructions. Perirectal fistulas may be present on the exam which may help to clue the physician into the diagnosis. Although this disease can present anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, it most commonly affects the terminal ileum.[7]

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is the other major component of inflammatory bowel disease. This disease has an unknown etiology. Patients often present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia. Other signs that may aid diagnosis are weight loss and pallor secondary to anemia.[8]

Microscopic Colitis

This is a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea. There are two subtypes of microscopic colitis: collagenous and lymphocytic colitis. It is diagnosed based on an endoscopic biopsy.[8]

Celiac Disease

This disease process occurs in individuals who develop an immune-mediated reaction triggered by the ingestion of gluten. Celiac disease occurs in only about 1% of the population, but the incidence is rising. Symptoms include abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and weight loss. Diagnosis requires a biopsy of the intestine showing villous atrophy. Most patients will produce the antibody against tissue transglutaminase.[9]

Chronic Pancreatitis

Pancreatic enzymes are essential for proper digestion of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. Patients with chronic pancreatitis will develop recurrent bouts of acute pancreatitis and chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pancreatitis will eventually lead to scarring and fibrosis of the pancreas, which will decrease the number of pancreatic enzymes, and malabsorption. This will lead to steatorrhea and weight loss.[10]

Lactose Intolerance

The ability to digest lactose comes from an enzyme present in the intestine called lactase. This allows the lactose to be broken down into simple sugar and be absorbed. When this enzyme is absent, the lactose is not able to be absorbed by the intestine. This will increase the osmolality within the lumen of the intestine producing watery diarrhea shortly after the ingestion of lactose-containing foods.[11]

Malabsorption Syndromes

This term is very nonspecific and encompasses any disorder where the intestine has a decreased ability to absorb nutrients while not requiring intravenous supplementation for health and/or growth.[12]

Post-cholecystectomy Diarrhea

Diarrhea after a cholecystectomy occurs in up to 12% of patients. Over time, symptoms generally resolve on their own without intervention.[13] Since the gallbladder is removed, the bile produced by the liver directly enters the colon instead of being stored. The increased amount of bile acids in the colon produces diarrhea.[14]

Chronic Infections

Certain long-lasting infections of the gastrointestinal tract can be linked to chronic diarrhea. A few of these infections include C. difficile, Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella, Shigella, Entamoeba histolytica, E. Coli, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Whipple Disease, and Cyclospora.[15] A clinician should always have a suspicion for an infectious cause of diarrhea. Risk factors include travel and immunosuppression.

Epidemiology

Chronic diarrhea is a condition that affects approximately 5% of the population at any given point in time, although the exact prevalence is unknown. Women are more likely than men to experience abdominal pain, bloating, discomfort, and bloating. The prevalence of diarrhea, however, is approximately equal in males and females alike. Diarrhea was less common among those above the age of 60.[16]

History and Physical

History and physical exam vary widely from patient to patient depending on the severity and etiology of the disease. The physical exam is often normal in patients with chronic diarrhea; however, signs of unintentional weight loss points towards a more severe disease. Although history and physical exam will rarely lead to a specific cause of chronic diarrhea, it is an integral part of any patient encounter. It is important to have the patient describe their diarrhea. Specific descriptions such as hematochezia, mucus in the stool, or steatorrhea help narrow the differential diagnosis greatly. Some specific physical exam signs may clue the examiner towards a diagnosis.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

These patients will often present with bouts of bloating and abdominal pain. The pain may be relieved by defecation. Symptoms will also typically be associated with stress.[3]

Medications

These patients may have a history of being recently started on a new medication, so it is important to do a thorough medication reconciliation in all patients presenting with chronic diarrhea.[4]

Crohn Disease

The physical exam is often unrevealing, but the presence of perirectal fistulas is associated with more advanced disease. These patients may also describe mucus or blood in the stool.[7]

Ulcerative Colitis

This is another disease where the physical exam often does not help diagnosis in early disease but may aid in advanced disease. Patients will complain of hematochezia. Due to blood loss, patients may have signs and symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue and pallor.[8]

Microscopic Colitis

The physical exam is typically normal on these patients as well. The description of very watery diarrhea may help with this diagnosis.[8]

Celiac Disease

This disease process is one that the examiner needs to suspect for any patient with chronic diarrhea and abdominal cramping. Patients may present with a history of other autoimmune conditions. A blood test for an antibody against tissue transglutaminase is highly suggestive of this disease.[9]

Chronic Pancreatitis

This disease is slightly easier to suspect based on history and physical examination. Patients will have recurrent bouts of abdominal pain and often require admission to the hospital for pancreatitis. Patients may describe their diarrhea as fatty.[10]

Lactose Intolerance

Patients will generally have a benign physical examination. These patients will typically have symptoms of bloating, gas, cramps, and diarrhea shortly after ingesting lactose.[11] Patients may complain of these symptoms around the same time each day if they have a normal routine of ingesting lactose-based foods each day, such as cereal for breakfast.

Post-cholecystectomy Diarrhea

The physical exam will be relatively nonspecific, but these patients have a history of recent cholecystectomy. Examining the abdomen will reveal a surgical incision site.[13]

Chronic Infections

Patients will have non-specific symptoms. They may have a history of recent travel, HIV infection, or chronic steroid use.[15]

Evaluation

For all patients complaining of chronic diarrhea, a thorough history and physical exam are necessary. The following laboratory testing should also take place for every patient with chronic diarrhea:

- Complete blood count with differential to examine for infection and anemia

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein to look for infections

- Thyroid function tests to screen for hyperthyroidism

- Complete metabolic profile to search for electrolyte abnormalities, renal function

- Total protein and albumin to look for signs of protein malnutrition

- Stool occult blood to look for a gastrointestinal bleed

If the patient has any alarming symptoms, referral for endoscopy is necessary. Alarm symptoms include:

- Symptom onset after age 50

- Rectal bleeding/melena

- Nocturnal pain or diarrhea

- Progressive abdominal pain

- Unexplained weight loss, fever, or other systemic symptoms

- Laboratory abnormalities such as iron deficiency anemia, elevated ESR/CRP, elevated fecal calprotectin, or fecal occult blood

- First degree relative with inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer

If patients do not have alarming symptoms, stool laboratory assessment is a recommendation. If the patient has recent antibiotic use, checking the stool for C. difficile toxin is warranted; C. difficile toxin should be reviewed on all patients with chronic diarrhea, regardless of antibiotic use, if their diarrhea classically fits the description of C. difficile: watery diarrhea occurring 3 or more times per day.

When categorizing the stool, it is essential to check for the following labs:

- Stool electrolytes

- Fecal leukocytes (fecal lactoferrin or fecal calprotectin are a substitute in place of fecal leukocytes)

- Fecal chymotrypsin and elastase

- Occult blood

- Stool fat (48 to 72 hour timed collection is ideal)

While chronic diarrhea has a very broad differential diagnosis, categorizing the stool can help narrow down the list.

Fecal leukocytes/calprotectin/lactoferrin are markers of inflammation. The presence of these markers will point towards inflammatory diarrhea, such as Crohn disease, or ulcerative colitis.

Fecal chymotrypsin and elastase are pancreatic enzymes that can present in the stool in the setting of pancreatic insufficiency. These two tests do not definitively diagnose pancreatic insufficiency. If these are positive on stool testing, the physician should check blood tests for pancreatic enzymes, and potentially refer to a gastroenterologist for further studies.

Steatorrhea shows that there is a problem with the absorption of fats. While many will attribute this to pancreatic insufficiency, it can also result from bile acid deficiency and SIBO.

For patients with watery diarrhea, stool electrolytes will further categorize their diarrhea into either osmotic diarrhea or secretory diarrhea based on the calculation of the stool osmotic gap. The calculation is as follows:

- 290 mOsm/kg - 2(Na[feces]+K[feces])

If the result of the above formula is less than 50 mOsm/kg, then the diarrhea is secretory. If the result is greater than 75 mOsm/kg, then the diarrhea is osmotic.[2]

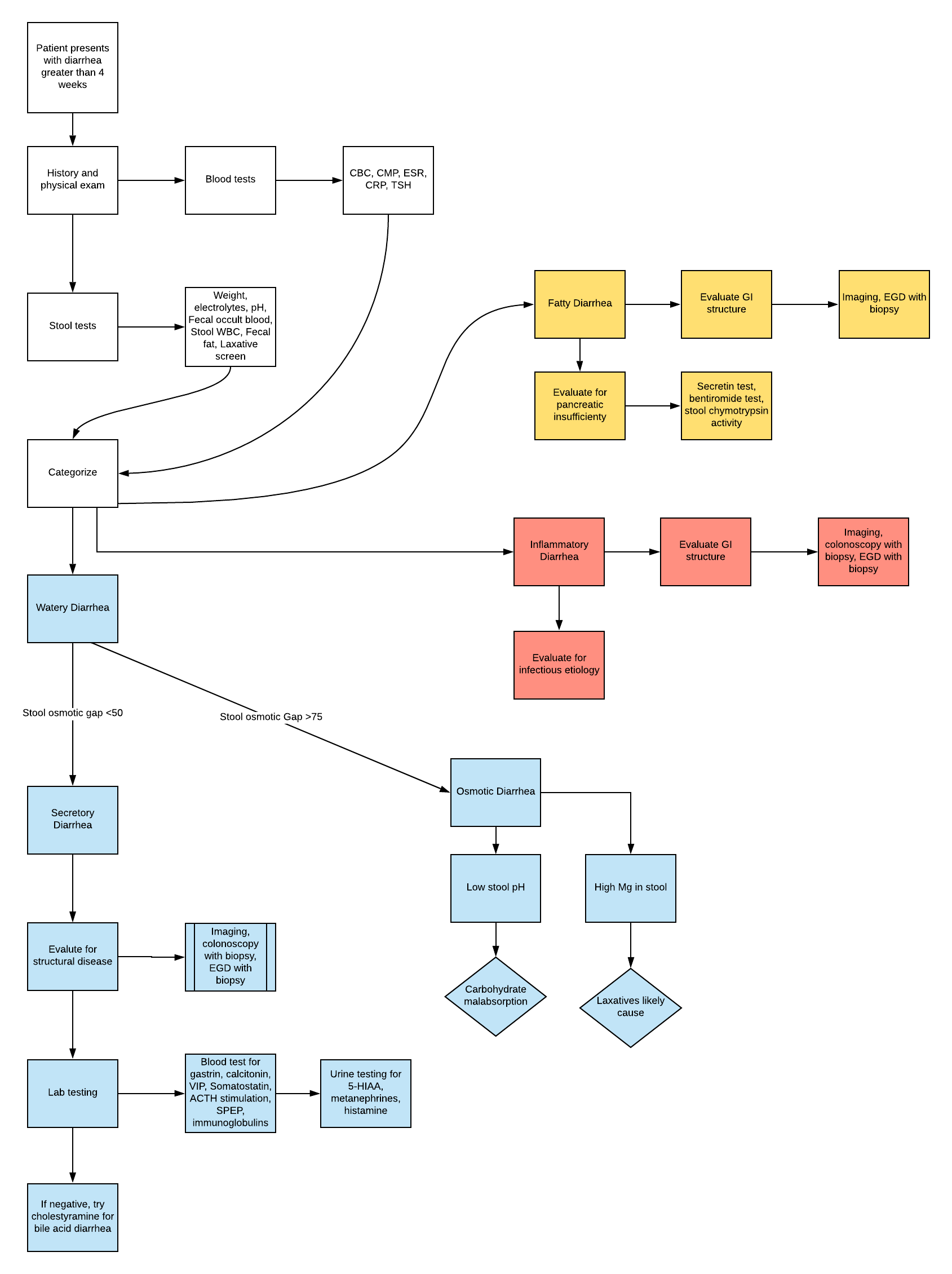

For a diagnostic algorithm, see the attached figure.

Treatment / Management

Treatment will vary, dependant on the specific diagnosis made after initial testing. If there is no diagnosis after testing, or if the diagnosis has no specific treatment, empiric treatment may be warranted. The typical first-line empiric therapy is opiate receptor agonists that act primarily in the gastrointestinal tract. Loperamide is a safe mu-receptor agonist used to decrease gut peristalsis.

Other medications used for chronic diarrhea include bile acid-binding resins such as cholestyramine. Clonidine is an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that also slows the intestinal tract, and is an option for diarrhea secondary to opioid withdrawal as well as diarrhea secondary to loss of noradrenergic innervation in patients with diabetes. The use of this medication has limitations due to the antihypertensive effect. However, this medication may be useful for patients with hypertension and chronic diarrhea.

Anticholinergic medications can be used to treat diarrhea as well. Tricyclic antidepressants which are used to treat depression or pain can also treat diarrhea.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea is extremely broad. Categorizing the type of diarrhea will help to narrow down the underlying cause.[17]

Watery Diarrhea

- Osmotic diarrhea

- Osmotic laxative use (magnesium, phosphate, or sulfate ingestion)

- Carbohydrate malabsorption (lactose, fructose)

- Celiac disease

- Sugar alcohols (mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol)

- Secretory

- Alcoholism

- Bacterial enterotoxins such as cholera

- Bile acid malabsorption

- Crohn disease in early ileocolitis

- Hyperthyroidism

- Medications (quinine, antibiotics, antineoplastics, biguanides, calcitonin, digitalis, colchicine, prostaglandins, ticlopidine)

- Microscopic colitis

- Neuroendocrine tumors (gastrinoma, vipoma, carcinoid tumors, mastocytosis)

- Nonosmotic laxatives (senna, docusate sodium)

- Functional

- Irritable bowel syndrome

Fatty Diarrhea

- Malabsorption syndromes

- Medications (orlistat, acarbose)

- Gastric bypass

- Celiac sprue

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Parasites (Giardia)

- Short bowel syndrome

- Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Tropical sprue

- Whipple disease

- Maldigestion

- Hepatobiliary disorders

- Inadequate luminal bile acid

- Pancreatic insufficiency

Inflammatory Diarrhea

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Crohn disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Diverticulitis

- Ulcerative jejunoileitis

- Invasive infections

- Clostridium difficile colitis

- Bacterial infections (tuberculosis, yersiniosis)

- Parasites (Entamoeba)

- Ulcerating viral infections (cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus)

- Neoplasms

- Colon cancer

- Lymphoma

- Villous adenocarcinoma

- Radiation colitis

Prognosis

The prognosis for chronic diarrhea varies widely based on the cause of chronic diarrhea. For patients with a non-specific diagnosis, the prognosis is generally very good. The standard therapy used to treat nonspecific diarrhea such as opioid agonists are very effective.[2]

Complications

Complications of chronic diarrhea will vary based on the specific cause. In general, the main complication present for all patients with chronic diarrhea is malabsorption. If the transit time is low in the intestines, the proper amount of nutrients and fluids cannot be absorbed. The physician should look for signs of malnutrition such as anemia and unintentional weight loss. Another complication can be dehydration and acute kidney injury from dehydration. If the gastrointestinal tract cannot absorb enough fluids, the dehydration will start to affect the renal function. Electrolyte abnormalities can also be concerning and require monitoring for replacement need.[2]

Consultations

Consultation to a gastroenterologist is often necessary for severe diarrhea and to further investigate the cause of diarrhea. In settings of inflammatory diarrhea, endoscopy may be necessary to obtain a specific diagnosis.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is crucial for patients to talk to their primary care physician if they are experiencing loose, watery stools, which occurs three or more times per day for over four weeks. This state of affairs is likely a symptom of an underlying disease process which requires diagnosis and treatment.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients who experience chronic diarrhea are those who have loose or watery stools occurring three or more times per day lasting for 4 weeks or longer. Although an integral component of diagnosis, history, and physical exam typically nonspecific. History should focus on the timing of diarrhea relative to ingestion. All patients with chronic diarrhea need screening for malabsorption, electrolyte abnormalities, and acute kidney injury. Radiographic imaging should look for bowel obstruction, strictures, or fistulae.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The most important part of dealing with chronic diarrhea that the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, and internist face is finding a specific diagnosis.[level I] All patients should have blood tests to check for anemia, kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and celiac disease in addition to stool tests for inflammation. [Level I] Pharmacists can review medication records for potential drug-drug interactions or drug adverse events, and alert other professionals if they find any. The diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is after blood and stool testing. [Level II] All patients should have screening for fecal blood loss. [Level II] Specialty-trained nursing will often have the most frequent and earliest contact with patients and can be among the first to be aware of the presence of chronic diarrhea. If symptoms do not resolve after using first-line agents, the situation warrants referral to a specialist.[18] [Level V] All health professions on the healthcare team need to collaborate and communicate across interprofessional lines so that diagnosis and treatment are well coordinated.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Shane AL, Mody RK, Crump JA, Tarr PI, Steiner TS, Kotloff K, Langley JM, Wanke C, Warren CA, Cheng AC, Cantey J, Pickering LK. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 Nov 29:65(12):e45-e80. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix669. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29053792]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchiller LR, Pardi DS, Sellin JH. Chronic Diarrhea: Diagnosis and Management. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2017 Feb:15(2):182-193.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.07.028. Epub 2016 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 27496381]

Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Van Dyke C, Melton LJ 3rd. Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991 Oct:101(4):927-34 [PubMed PMID: 1889716]

Philip NA, Ahmed N, Pitchumoni CS. Spectrum of Drug-induced Chronic Diarrhea. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2017 Feb:51(2):111-117. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000752. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28027072]

Burbure N, Lebwohl B, Arguelles-Grande C, Green PH, Bhagat G, Lagana S. Olmesartan-associated sprue-like enteropathy: a systematic review with emphasis on histopathology. Human pathology. 2016 Apr:50():127-34. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.12.001. Epub 2015 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 26997446]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMazal J. Crohn disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Radiologic technology. 2014 Jan-Feb:85(3):297-316; quiz 317-20 [PubMed PMID: 24395894]

Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's disease. Lancet (London, England). 2012 Nov 3:380(9853):1590-605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. Epub 2012 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 22914295]

Adams SM, Bornemann PH. Ulcerative colitis. American family physician. 2013 May 15:87(10):699-705 [PubMed PMID: 23939448]

Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet (London, England). 2018 Jan 6:391(10115):70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8. Epub 2017 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 28760445]

Anaizi A, Hart PA, Conwell DL. Diagnosing Chronic Pancreatitis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2017 Jul:62(7):1713-1720. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4493-2. Epub 2017 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 28315036]

Rosado JL. [Lactose intolerance]. Gaceta medica de Mexico. 2016 Sep:152 Suppl 1():67-73 [PubMed PMID: 27603891]

Clark R, Johnson R. Malabsorption Syndromes. The Nursing clinics of North America. 2018 Sep:53(3):361-374. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2018.05.001. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30100002]

Sauter GH, Moussavian AC, Meyer G, Steitz HO, Parhofer KG, Jüngst D. Bowel habits and bile acid malabsorption in the months after cholecystectomy. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2002 Jul:97(7):1732-5 [PubMed PMID: 12135027]

Arlow FL, Dekovich AA, Priest RJ, Beher WT. Bile acid-mediated postcholecystectomy diarrhea. Archives of internal medicine. 1987 Jul:147(7):1327-9 [PubMed PMID: 3606289]

Navaneethan U, Giannella RA. Mechanisms of infectious diarrhea. Nature clinical practice. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2008 Nov:5(11):637-47. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1264. Epub 2008 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 18813221]

Sandler RS, Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Ricci JA, Zorich NL. Abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea in the United States: prevalence and impact. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2000 Jun:45(6):1166-71 [PubMed PMID: 10877233]

Juckett G, Trivedi R. Evaluation of chronic diarrhea. American family physician. 2011 Nov 15:84(10):1119-26 [PubMed PMID: 22085666]

Arasaradnam RP, Brown S, Forbes A, Fox MR, Hungin P, Kelman L, Major G, O'Connor M, Sanders DS, Sinha R, Smith SC, Thomas P, Walters JRF. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology, 3rd edition. Gut. 2018 Aug:67(8):1380-1399. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315909. Epub 2018 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 29653941]

Dutra B, Siddiqui S, Everett J. A Clinical Approach to Chronic Diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar:162(3):707-709. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.038. Epub 2021 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 34331913]

Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Jensen ET, Kim HP, Egberg MD, Lund JL, Moon AM, Pate V, Barnes EL, Schlusser CL, Baron TH, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2021. Gastroenterology. 2022 Feb:162(2):621-644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.017. Epub 2021 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 34678215]