Introduction

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death for both sexes in the United States, with 702,880 fatalities recorded in 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly half of these deaths occur outside of a hospital, with three-quarters taking place in the home and half of those being unwitnessed. Among adult patients, ventricular fibrillation (VF) is the most common cause of sudden cardiac arrest.

Cardiac defibrillation is the process of delivering a transthoracic electrical current to a patient experiencing one of 2 life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias: VF or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT). Both conditions are treated identically under Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) guidelines. The definitive treatment for VF is electrical defibrillation, which is most effective when performed immediately after VF onset. The success rate of defibrillation declines by nearly 10% for each minute of delay.

The first recorded case of open-chest defibrillation in a human was performed in 1947 by American cardiac surgeon Claude Beck on a 14-year-old patient undergoing surgery for a congenital chest defect. In 1957, William Kouwenhoven developed the first external defibrillator, weighing over 250 pounds (120 kg). By 1961, advancements led to a portable defibrillator weighing approximately 45 pounds.[1] Survival rates for adult patients who experience nontraumatic cardiac arrest and receive emergency medical services resuscitation are low, with only 10.8% surviving to be discharged from the hospital. In contrast, in-hospital cardiac arrest patients have a survival rate of up to 25.5%, largely due to defibrillation being performed closer to the onset of VF.[2][3][4] According to the American Heart Association, approximately 350,000 people experience out-of-hospital cardiac arrest annually.[5]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

VF occurs when the normal transmission of the cardiac impulse through the heart’s electrical conduction system is interrupted. This can occur in the setting of coronary ischemia or acute myocardial infarction. VF can also occur due to sudden interruptions to the cardiac impulse by events such as an electrical shock; a blow to the chest (commotio cordis); premature ventricular contractions, especially the “R on T” type; abnormal tachycardic rhythms such as ventricular tachycardia; and syndromes such as QT prolongation.

The chaotic, dysrhythmic firing of multiple irritable myocardial foci in the ventricles causes fibrillation of the ventricles. This produces a loss of normal ventricular contraction with the resultant cessation of cardiac output. The clinical result is a sudden cardiac arrest. While defibrillation is highly effective in treating VF and pulseless VT, its effectiveness is time-dependent. Untreated VF will rapidly deteriorate into asystole, from which resuscitation rates are dismal. For untreated VF or VT, the likelihood of resuscitation decreases by up to 10% per minute. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can provide temporary oxygenation and circulation until defibrillation becomes available. Conventional manual CPR, combining chest compressions with rescue breathing, when done correctly, can provide up to 33% of normal cardiac output and oxygenation. The provision of early CPR can triple the rate of survival from witnessed sudden cardiac arrest.

The definitive treatment for VF or its equivalent, pulseless VT, is electrical defibrillation. Contrary to popular belief, defibrillation does not “jump-start” the heart. Rather, it produces nearly simultaneous depolarization of a critical mass of the myocardium, causing momentary cessation of all cardiac activity. Under ideal circumstances, a viable site within the heart’s intrinsic electrical conduction system will then spontaneously initiate an electrical impulse that can restore normal propagation of the heart’s cardiac cycle, with a resultant restoration of ventricular contraction and, hence, a pulse.

Traditional “manual” defibrillation is provided by medical or paramedical personnel trained in electrocardiogram (EKG), dysrhythmia recognition, and emergency cardiac care. Today, the widespread availability of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) allows trained first responders and, in some instances, the lay public to provide early defibrillation to victims of sudden cardiac arrest. AEDs interpret the EKG rhythm automatically, determine if a “shockable” rhythm is present, self-charge to the required energy level, and provide the responder with verbal prompts to successfully perform the defibrillation process.[6][7]

Indications

Early electrical defibrillation is the treatment of choice for VF and pulseless VT without a pulse.

Contraindications

Defibrillation has no contraindications. A pacemaker or implanted cardiac defibrillator does not change the indication or performance of the procedure when a shockable rhythm is present.

Equipment

Defibrillators are broadly categorized into these categories:

- AEDs

- These are found in public spaces.

- Wearable cardioverter defibrillators

- This is a vest that has a defibrillator built into it.

- Implanted cardioverter defibrillators

- These small devices require surgical placement in the chest.

In this topic, we will discuss defibrillation by trained medical personnel requiring a cardiac monitor with defibrillation capability or an AED.

Personnel

Most persons who perform defibrillation are medical personnel who have received additional training in cardiac resuscitation through courses such as the ACLS or Pediatric Advanced Life Support programs.

Preparation

While the defibrillator is prepared, resuscitation, including CPR, continues. Once a defibrillator is available, it should be used as soon as possible and take precedence over other resuscitative measures in a patient with VT or VF. Defibrillation delivers an electrical shock across the chest, either by placing a pair of manual paddles on the chest or applying adhesive “hands-free” pads. Current defibrillators typically use a biphasic waveform with lower energy levels to achieve effective defibrillation. This increased ability to terminate ventricular dysrhythmias makes defibrillators utilizing biphasic waveforms preferred to the older, monophasic waveform.

Technique or Treatment

Adult Defibrillation

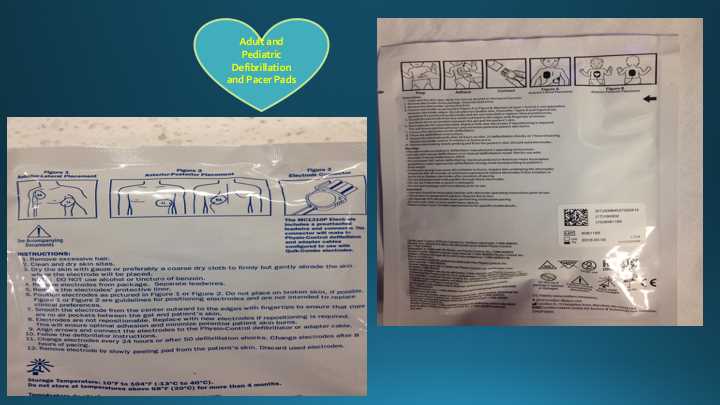

The defibrillator paddles are placed on the chest, with 1 paddle placed along the upper right sternal border and the other placed at the cardiac apex. Alternatively, "hands-free" defibrillator pads may be used. The hands-free pads are placed in the same location as the paddles; alternatively, they may be placed in an anteroposterior configuration (see Images. Packaged Defibrillation Pads and Defibrillation Pad Positioning).

The cardiac monitor/defibrillator is then placed in the defibrillation mode, and the defibrillator’s capacitor is charged. The manufacturer presets the initial energy level for biphasic manual defibrillators. The 2015 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for defibrillation state that using the manufacturer’s recommended dose of the first defibrillation shock is reasonable. On a biphasic defibrillator, this is usually between 120 to 200 joules. On a monophasic defibrillator, this is usually 360 joules. If the manufacturer's recommended dose is unavailable, the AHA recommends giving the maximum available dose.

Once fully charged, the scene is checked to ensure that no one is touching the patient or in contact with anything touching the patient. The "shock" button is pressed, allowing the stored charge to be delivered across the chest from paddle to paddle or hands-free pad to pad. After the shock is delivered, CPR is immediately resumed for 2 minutes. After 2 minutes of high-quality CPR following the initial defibrillation, the patient's pulse is palpated, and the electrical rhythm is checked on the monitor to determine if VF or pulseless VT has been terminated and if a pulse has been restored.

If VF or pulseless VT persists, CPR is immediately resumed, and the patient may be shocked again. The manufacturer recommended dose (120-200 joules) for a biphasic defibrillator, and 360 joules is recommended for a monophasic defibrillator. Importantly, every successive electrical defibrillation dose should be of equal or greater value until the maximum available dose is reached. A step-wise increase in defibrillation dose is recommended according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

According to the ACLS VF/pulseless VT algorithm outlined by AHA, 1 mg of epinephrine should be administered intravenously every 3 to 5 minutes during the resuscitation after the first unsuccessful defibrillation. High-quality CPR is immediately resumed after the second shock for 2 minutes. Suppose VF or pulseless VT persists at the next pulse and rhythm check. In that case, the ACLS algorithm allows 300 mg of amiodarone to be administered intravenously as a bolus during the resuscitation. Suppose additional doses of antiarrhythmic drugs are needed. In that case, 150 mg of amiodarone may be given, or 1 mg/kg to 1.5 mg/kg of lidocaine as a first dose, and 0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg as a second dose may be administered. According to the current AHA guidelines, epinephrine and amiodarone are preferred over lidocaine.[8]

The 30-day survival rate was not higher with an intraosseous-first vascular access approach than with an intravenous-first strategy among patients who had out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and required drug therapy.[9] Among patients who had out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, there was not a significant difference in sustained return of spontaneous circulation between initial intravenous and intraosseous vascular access.[10]

Pediatric Defibrillation

For pediatric patients, the initial energy dose delivered for defibrillation is recommended to be 2 joules/kg. Subsequent defibrillations in pediatric patients can be dosed at 4 joules/kg or higher with a maximum dose of 10 joules/kg. Infant pads are needed if the patient is under 10 kg or less than 1 year. Adult pads are used if the patient is over 10 kg or 1 year old. If small pads are unavailable, adult pads can be used in the anterior-posterior position. The user must ensure that the pads do not touch. The pads cannot be cut to fit the patient either. A delay in defibrillation due to a lack of infant pads or a low-voltage defibrillator is not recommended. A shock with adult pads/defibrillator at an adult dose is better than not delivering a shock. Ideally, patients younger than 1 year old should be defibrillated using a manual defibrillator. If this is not available, a pediatric attenuator can be used. In children aged 8 years or younger or under 25 kg, an AED with a pediatric dose attenuator is used. Standard adult AED pads and cable systems are used in children 8 years and older or 25 kg and heavier.[11][12]

Internal Defibrillation

In the case of VF or pulseless VT during thoracotomy procedures such as emergency department thoracotomy or cardiac surgery, internal defibrillation is performed. This follows the same algorithm as external defibrillation except for a change in the defibrillation energy dose. In internal defibrillation, an initial dose of 20 joules is recommended to avoid burn-like injury to the myocardium. Care should be taken to avoid coronary vessels and prevent vessel damage. Subsequent doses can be increased to a maximum of 40 joules. Sterile internal pads must be used for internal defibrillation and should be readily available during any thoracotomy procedures.[13]

Refractory VF

Even with advancements in defibrillation technology, almost half of the patients with VF may remain in refractory VF despite using multiple defibrillation attempts. Double sequential external defibrillation is a technique in which 2 defibrillators provide rapid sequential shocks by placing defibrillation pads in 2 different planes. Vector change (VC) defibrillation is switching anterior-lateral pads to the anterior-posterior position (see Image. Double Defibrillation Pad Placement). The survival to hospital discharge in patients with refractory VF occurred more frequently in those receiving VC or DSED defibrillation as compared to the patients who received standard defibrillation.[14]

Transthoracic impedance (TTI) measures the thoracic resistance to the current flow and is used to verify that the defibrillation electrodes are adequately attached to the patient's thorax. According to the reviewed literature, the range of TTI in humans is between 12 to 212 ohms. The coupling device, electrode pressure, and electrode size greatly affected TTI.[15]

Complications

When a patient is defibrillated, the stored energy is immediately released. The shock is delivered at whatever point the cardiac cycle happens to be in. Suppose an electrical shock was to be administered to someone who is not in VF or pulseless VT. In that case, the energy can be applied during the relative refractory period, corresponding to the latter part of the T wave of the cardiac cycle. Suppose an electrical charge were to be administered at this vulnerable point.

In that case, it is possible to induce VF by the “R-on-T phenomenon," which would result in a patient who initially had a pulse being put into cardiac arrest. For this reason, defibrillation is only performed for VF or pulseless VT. For a patient who is not in cardiac arrest but needs electrical cardioversion for an unstable tachycardic rhythm, synchronized cardioversion is performed instead of defibrillation to avoid this complication. For a patient with VT and a palpable pulse who presents with signs of hypoperfusion and hemodynamic instability, synchronized cardioversion with 100 joules of energy dose is recommended.[16]

Clinical Significance

Cardiac defibrillation is the process of delivering a transthoracic electrical current to a patient experiencing 1 of 2 life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias: VF or pulseless VT. Under ACLS guidelines, both conditions are treated identically. Heart disease remains the leading cause of death for any sex in the United States, with 702,880 fatalities recorded in 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly half of these deaths occur outside of a hospital, with three-quarters taking place in the home and half of those being unwitnessed. Among adult patients, VF is the most common cause of sudden cardiac arrest.

The definitive treatment for VF is electrical defibrillation, which is most effective when performed immediately after VF onset. The success rate of defibrillation declines by nearly 10% for each minute of delay, and after 10 minutes of VF, the chances of successful resuscitation drop to near 0. For this reason, many communities have implemented early defibrillation programs that train public members to use automated external defibrillators (AEDs), which can dramatically improve survival outcomes by reducing the time to first shock.[17][18]

AEDs play a critical role in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by providing early defibrillation before emergency medical services arrive. Designed for trained professionals and bystanders, AEDs automatically analyze cardiac rhythms and deliver shocks only when indicated. Public access defibrillation programs have significantly improved survival rates, particularly when defibrillation occurs within the first 3 to 5 minutes of arrest. Study results indicate that early defibrillation with AEDs can improve survival to hospital discharge rates to over 50%, compared to less than 11% when defibrillation is delayed. Additionally, drones have been used to deliver AEDs to the site of suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest before ambulance arrival in two-thirds of cases, with a clinically significant median time benefit of more than 3 minutes, potentially decreasing the time to AED attachment and improving outcomes.[19]

AEDs are integral to emergency response systems in clinical practice, including emergency medical services, hospitals, and public spaces such as airports, malls, and schools. Their role extends to in-hospital use for rapid response teams and in situations requiring immediate defibrillation before ACLS interventions. AEDs also improve neurological outcomes by reducing ischemic injury associated with prolonged cardiac arrest. Despite their effectiveness, AED accessibility and public awareness remain challenges. Expanding AED deployment, integrating them into emergency protocols, and promoting public education on their use are essential strategies for maximizing their clinical impact and improving survival rates in sudden cardiac arrest cases.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective defibrillation in cardiac arrest requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach to optimize patient-centered care, enhance outcomes, and ensure patient safety. Clinicians must work seamlessly as a team, each fulfilling distinct yet complementary roles. Advanced clinicians provide rapid decision-making, ensuring appropriate rhythm recognition and defibrillation timing while guiding Advanced Cardiac Life Support protocols. Nurses are crucial in preparing and delivering defibrillation, maintaining chest compressions, and administering medications. Paramedics and emergency medical technicians are often the first responders in out-of-hospital settings, applying AEDs or manual defibrillators to initiate early treatment. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring the availability and correct administration of emergency medications such as epinephrine and amiodarone, which are critical in ACLS protocols.

Interprofessional communication and care coordination are essential to streamline the defibrillation process and minimize delays that could compromise survival. Clear, closed-loop communication is critical to ensure all team members understand their roles and responsibilities, particularly during high-stress situations like cardiac arrest. Standardized protocols, including mock resuscitation drills and debriefings, improve team performance and patient outcomes. Integrating technology such as real-time audiovisual feedback on chest compressions and defibrillation, electronic health record alerts, and drone-delivered AEDs in out-of-hospital settings further enhances efficiency. By fostering collaboration, continuous education, and adherence to best practices, healthcare teams can improve survival rates, reduce post-resuscitation complications, and provide safer, more effective patient-centered care. There is no question that defibrillation is an interprofessional event, but the team must be organized and functional to achieve success rates.[20][21]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Defibrillation Pad Positioning. The image depicts the correct placement of the pads during defibrillation and cardioversion. This image also illustrates the heart's position and intrathoracic energy flow during shock.

PhilippN, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Naser N. On Occasion of Seventy-five Years of Cardiac Defibrillation in Humans. Acta informatica medica : AIM : journal of the Society for Medical Informatics of Bosnia & Herzegovina : casopis Drustva za medicinsku informatiku BiH. 2023 Mar:31(1):68-72. doi: 10.5455/aim.2023.31.68-72. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37038491]

Wang PL, Brooks SC. Mechanical versus manual chest compressions for cardiac arrest. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Aug 20:8(8):CD007260. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007260.pub4. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30125048]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSrinivasan NT, Schilling RJ. Sudden Cardiac Death and Arrhythmias. Arrhythmia & electrophysiology review. 2018 Jun:7(2):111-117. doi: 10.15420/aer.2018:15:2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29967683]

Pacheco RL, Trevizo J, Souza CA, Alves G, Sakaya B, Thiago L, Góis AFT, Riera R. What do Cochrane systematic reviews say about cardiac arrest management? Sao Paulo medical journal = Revista paulista de medicina. 2018 Mar:136(2):170-176. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2018.0083230318. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29791610]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKrychtiuk KA, Starks MA, Al-Khalidi HR, Mark DB, Monk L, Yow E, Kaltenbach L, Jollis JG, Al-Khatib SM, Bosworth HB, Ward K, Brady S, Tyson C, Vandeventer S, Baloch K, Oakes M, Blewer AL, Lewinski AA, Hansen CM, Sharpe E, Rea TD, Nelson RD, Sasson C, McNally B, Granger CB, RACE-CARS NC Counties. RAndomized Cluster Evaluation of Cardiac ARrest Systems (RACE-CARS) trial: Study rationale and design. American heart journal. 2024 Nov:277():125-137. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2024.07.013. Epub 2024 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 39084483]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEl-Battrawy I, Borggrefe M, Akin I. Letter by El-Battrawy et al Regarding Article, "The Effects of Public Access Defibrillation on Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies". Circulation. 2018 Apr 10:137(15):1646-1647. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030567. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29632161]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoyal A, Sciammarella JC, Chhabra L, Singhal M. Synchronized Electrical Cardioversion. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489237]

Oechslin E. [Treatment strategies in mechanical and electrical cardiovascular failure]. Therapeutische Umschau. Revue therapeutique. 1996 Aug:53(8):646-57 [PubMed PMID: 8830422]

Couper K, Ji C, Deakin CD, Fothergill RT, Nolan JP, Long JB, Mason JM, Michelet F, Norman C, Nwankwo H, Quinn T, Slowther AM, Smyth MA, Starr KR, Walker A, Wood S, Bell S, Bradley G, Brown M, Brown S, Burrow E, Charlton K, Claxton Dip A, Dra'gon V, Evans C, Falloon J, Foster T, Kearney J, Lang N, Limmer M, Mellett-Smith A, Miller J, Mills C, Osborne R, Rees N, Spaight RES, Squires GL, Tibbetts B, Waddington M, Whitley GA, Wiles JV, Williams J, Wiltshire S, Wright A, Lall R, Perkins GD, PARAMEDIC-3 Collaborators. A Randomized Trial of Drug Route in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. The New England journal of medicine. 2025 Jan 23:392(4):336-348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407780. Epub 2024 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 39480216]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVallentin MF, Granfeldt A, Klitgaard TL, Mikkelsen S, Folke F, Christensen HC, Povlsen AL, Petersen AH, Winther S, Frilund LW, Meilandt C, Holmberg MJ, Winther KB, Bach A, Dissing TH, Terkelsen CJ, Christensen S, Kirkegaard Rasmussen L, Mortensen LR, Loldrup ML, Elkmann T, Nielsen AG, Runge C, Klæstrup E, Holm JH, Bak M, Nielsen LR, Pedersen M, Kjærgaard-Andersen G, Hansen PM, Brøchner AC, Christensen EF, Nielsen FM, Nissen CG, Bjørn JW, Burholt P, Obling LER, Holle SLD, Russell L, Alstrøm H, Hestad S, Fogtmann TH, Buciek JUH, Jakobsen K, Krag M, Sandgaard M, Sindberg B, Andersen LW. Intraosseous or Intravenous Vascular Access for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. The New England journal of medicine. 2025 Jan 23:392(4):349-360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407616. Epub 2024 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 39480221]

Wolfe HA, Morgan RW, Zhang B, Topjian AA, Fink EL, Berg RA, Nadkarni VM, Nishisaki A, Mensinger J, Sutton RM, American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigator. Deviations from AHA guidelines during pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation are associated with decreased event survival. Resuscitation. 2020 Apr:149():89-99. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.01.035. Epub 2020 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 32057946]

Egan J, Atkins DL. Defibrillation in children: why a range in energy dosing? Current pediatric reviews. 2013:9(2):134-8 [PubMed PMID: 25417034]

Pugsley WB, Baldwin T, Treasure T, Sturridge MF. Low energy level internal defibrillation during cardiopulmonary bypass. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1989:3(3):273-5 [PubMed PMID: 2624794]

Cheskes S, Verbeek PR, Drennan IR, McLeod SL, Turner L, Pinto R, Feldman M, Davis M, Vaillancourt C, Morrison LJ, Dorian P, Scales DC. Defibrillation Strategies for Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine. 2022 Nov 24:387(21):1947-1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207304. Epub 2022 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 36342151]

Heyer Y, Baumgartner D, Baumgartner C. A Systematic Review of the Transthoracic Impedance during Cardiac Defibrillation. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Apr 6:22(7):. doi: 10.3390/s22072808. Epub 2022 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 35408422]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcDonough M. Treating ventricular tachycardia. Journal of continuing education in nursing. 2009 Aug:40(8):342-3. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20090723-09. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19681568]

Kiyohara K, Nitta M, Sato Y, Kojimahara N, Yamaguchi N, Iwami T, Kitamura T. Ten-Year Trends of Public-Access Defibrillation in Japanese School-Aged Patients Having Neurologically Favorable Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. The American journal of cardiology. 2018 Sep 1:122(5):890-897. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.05.021. Epub 2018 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 30057229]

Zijlstra JA, Koster RW, Blom MT, Lippert FK, Svensson L, Herlitz J, Kramer-Johansen J, Ringh M, Rosenqvist M, Palsgaard Møller T, Tan HL, Beesems SG, Hulleman M, Claesson A, Folke F, Olasveengen TM, Wissenberg M, Hansen CM, Viereck S, Hollenberg J, COSTA study group. Different defibrillation strategies in survivors after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2018 Dec:104(23):1929-1936. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312622. Epub 2018 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 29903805]

Schierbeck S, Nord A, Svensson L, Ringh M, Nordberg P, Hollenberg J, Lundgren P, Folke F, Jonsson M, Forsberg S, Claesson A. Drone delivery of automated external defibrillators compared with ambulance arrival in real-life suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a prospective observational study in Sweden. The Lancet. Digital health. 2023 Dec:5(12):e862-e871. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00161-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38000871]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSociety of Thoracic Surgeons Task Force on Resuscitation After Cardiac Surgery. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Expert Consensus for the Resuscitation of Patients Who Arrest After Cardiac Surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2017 Mar:103(3):1005-1020. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.10.033. Epub 2017 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 28122680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFigueroa MI, Sepanski R, Goldberg SP, Shah S. Improving teamwork, confidence, and collaboration among members of a pediatric cardiovascular intensive care unit multidisciplinary team using simulation-based team training. Pediatric cardiology. 2013 Mar:34(3):612-9. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0506-2. Epub 2012 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 22972517]