Introduction

Elbow injuries are a frequent occurrence in the skeletally immature pediatric population. The metaphysis of the distal humerus is most susceptible to fractures in this population as it is an area of transition from a tubular configuration to a more flattened triangular cross-section. In addition to this anatomical peculiarity, ligamentous laxity in this age group predisposes pediatric patients between the age of 4 and 8 years to supracondylar fractures of the humerus. Typically, malunion of supracondylar fractures often leads to cubitus varus, or "gunstock deformity."

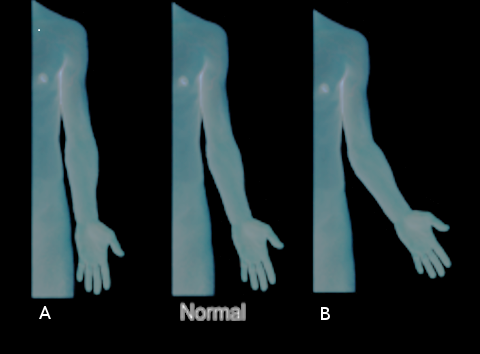

This condition is a triplanar malalignment of the elbow, characterized by varus angulation in the coronal plane, extension in the sagittal plane, and internal rotation in the transverse plane. Although it is frequently regarded as a purely cosmetic problem in children, it occasionally causes late-onset lateral elbow pain, symptomatic elbow posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI), triceps snapping, progressive ulnar and elbow joint varus, ulnar neuropathy, or rarely, predispose to lateral humeral condyle fractures.[1] For this reason, it may be appropriate to offer surgical treatment in the vast majority of patients with this complaint. Various treatment options proposed include observation, hemiepiphysiodesis and growth alteration, and corrective osteotomy.[2] Corrective osteotomy is the preferred method, as it yields the highest probability for success.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Historically, the incidence of this deformity following supracondylar humerus fractures occurred in up to 30% cases. However, the incidence has decreased substantially with the operative treatment of these injuries.[4] Less commonly, this can occur after lateral condyle humeral fractures. Other causes include physeal injuries, osteonecrosis, infection, or rarely, tumorous conditions.[5]

Epidemiology

Congenital cubitus varus is an unlikely cause for the deformity; however, it does occur rarely. The cause is epiphyseal dysplasia of the humerus, whereby the epiphysis angulates towards the midline, which decreases the carrying angle of the elbow joint. The ossification of the elbow joint starts with the distal humeral epiphysis during the 12th week of gestation. It is during this window of time that epiphyseal dysplasia will lead to congenital cubitus varus.[6]

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

The distal humerus and the proximal radius and ulna forms the elbow joint. It is one of the most complex joints in the body, allowing flexion, extension, pronation, and supination. The ligamentous and bony anatomy provides static stability to the elbow joint. In full supination and extension, the elbow joint deviates between 5 and 15 degrees in the coronal plane known as the carrying angle or physiologic valgus of the elbow. In cubitus varus, the carrying angle decreases, and the hands are closer to the midline than expected.[7] The resulting structure and function of the elbow joint with cubitus varus deformity may be compromised.

Pathoanatomy

The medial deviation of the upper extremity mechanical axis, and the medially directed triceps force vector with this deformity, can ultimately lead to attenuation of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament and ulnar supination, causing symptomatic elbow PLRI. Bone remodeling in the axis of the elbow joint in immature children often restores elbow flexion, although the arc of elbow motion is altered with increased hyperextension and decreased flexion. However, there is little remodeling, and therefore correction, in the rotational component of the deformity. Additionally, these patients can have reduced range-of-motion in pronation.[8]

Internal rotation malunion of the distal humerus leads to several pathoanatomic features such as posterior trochlear, capitellar, and radial head overgrowth. These primary abnormalities lead to secondary adaptive changes, including increased anteroposterior trochlear articular arc and lateral shift of trochlear notch convexity. Furthermore, the ulna adjusts to a distal and medial location with increased varus, flexion, and external rotation. Ulnar nerve instability and delayed ulnar nerve palsy can also occur due to internal rotation malunion of the distal humerus or concomitant fibrosis and entrapment in the cubital tunnel. The nerve can sublux or even dislocate anterior to the medial humeral epicondyle and becomes entrapped in the fibrous bands of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle causing symptoms of ulnar nerve neuropathy.

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical examination are necessary for the evaluation of a patient with cubitus varus deformity. The presence of open wounds, stiffness, range-of-motion, scarring, and a complete neurovascular examination should take place in the initial visit. Rotational malalignment is determined by evaluating the differences in shoulder passive internal rotation in extension between the involved and uninvolved extremity during physical examination. Progression of deformity in a growing child requires a critical evaluation of radiographs and warrants further axial imaging for assessment of asymmetrical physeal growth abnormalities.

Cubitus varus deformity is commonly recognized 6 to 10 weeks after healing of the fracture and return of complete elbow motion. Varus angulation is mostly responsible for the unsightly appearance of the elbow, while any amount of flexion contracture or posterior angulation reduces the apparent deformity. Torsional malrotation exaggerates the appearance of the deformity. Untreated varus angulation typically remains stable, and rarely if ever, progresses with time. Progression can occur with asymmetric growth disturbance in the distal humeral physis. If left untreated, or if severe enough, cubitus varus may result in ulnar nerve entrapment and posterolateral rotatory instability from attenuation of the LUCL. Occasionally, PLRI is unmasked after surgical correction.

Evaluation

Full-length anterior-posterior radiographs (AP) of the injured and contralateral upper extremity are essential for defining the extent of deformity and estimating the humeral-elbow-wrist angles (HEW). The HEW angle provides the most accurate method for determining the correct carrying angle. A HEW angulation is represented with a (+) sign if the extremity alignment is valgus, while a varus angle is denoted with a (-) sign. This approach is used in favor of the Baumann’s angle due to its applicability in both the skeletally immature and adult population.

In the absence of long radiographs, the angle subtended between the center of the shaft to the center of the elbow and the center of the transverse diameter of the radius and ulna provides a reasonable approximation of the HEW angle. The goal of the osteotomies should be the restoration of the HEW angle as close as possible to the contralateral uninjured extremity with the desired correction defined by the difference in the angles between the two extremities. The lateral condylar prominence index is also calculated from the pre-operative AP radiographs of the affected extremity.[9]

The difference between the lateral and the medial width of the distal humerus from the mid humeral axis and is expressed as a percentage of the total width of the distal humerus. True lateral elbow radiographs allow evaluation of the degree of extension deformity that exists. The affected and unaffected extremity radiographs are traced on paper to determine the width of the wedges necessary for surgical correction. A similar technique is employed to determine the required amount of rotation when using the dome osteotomy corrective technique.

The severity of a cubitus varus deformity is graded as follows:

- Grade I - loss of physiologic valgus

- Grade II - varus of 0 to 10 degrees

- Grade III - varus of 11 to 20 degrees

- Grade IV - varus >20 degrees

Treatment / Management

Corrective osteotomy of the distal humerus is the procedure of choice, as it is most successful in reducing symptoms and recurrence of cubitus varus deformity. The goal of the osteotomy is to correct the alignment of the elbow joint to a normal range of 5 to 15 degrees, as well as create a stable joint. Numerous osteotomy techniques for surgical correction have been described, including straight and oblique lateral closing wedge, reverse V, triangle, dome, double dome, step cut, multiplanar, and external fixation with distraction osteogenesis.[10] However, no one technique is safer or more successful over others. Besides, it is uncertain whether the correction of axial rotational malunion is necessary to achieve better outcomes, as the carrying angle was not influenced by the degree of uncorrected torsional deformity in one study. This observation is important since attempts at correction through axial derotation often render the osteotomy site unstable from reduced cortical contact. However, the long-term consequences of uncorrected rotational malunion after corrective osteotomy are unknown. Pins, screws, staple, and tension band constructs with wires are typically used for internal fixation of the osteotomy in the pediatric population, as hardware prominence is not uncommon in this age group.(B2)

A recent study in children found that external fixation compared to internal fixation devices was cost-efficient, led to easier preoperative planning, and more straightforward removal in the post-operative period. However, medial and lateral column plates are often deemed necessary in adults, and occasionally in adolescents, to allow stable fixation and early motion to minimize stiffness. Unstable internal fixation, especially in adults, may permit the osteotomy to drift into a varus position, leading to recurrence and poor cosmetic outcome. Recently, some authors have used 3-D printed cutting guides to simplify the procedure and streamline correction of the three-dimensional deformity, although costs for producing these templates remain a concern. In patients with longstanding deformity, lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction may be necessary as an adjunct procedure to treat PLRI. However, this is rarely necessary for children or adolescents.

No recommendation exists for choosing the type of osteotomy, although the more complex three-dimensional corrections may be technically challenging in pediatric patients compared to adults. In a meta-analysis evaluating four different corrective osteotomies, the authors reported that no technique was safer or more effective. Medial open wedge osteotomy lengthens the medial side of the humeral metaphysis and can cause stretching of the ulnar nerve with potentially increased risks of tardy ulnar nerve palsy and chronic pain.

The lateral closing wedge osteotomy (LCWO) is the most commonly performed technique. It is a less technically demanding procedure, and some published series have reported lower complication rates than the more difficult triplanar corrective osteotomies. However, lateral condylar prominence causing a ‘pseudocubitus varus’ deformity is not an uncommon problem with this procedure and is related to the severity of the preoperative deformity. Unsightly scarring on the lateral side of the elbow can sometimes be a problem as well. Some authors have found that an oblique lateral closing wedge may minimize the incidence of lateral condylar prominence. Other authors believe that remodeling of the lateral prominence and hyperextension occurs when the osteotomy is performed on patients younger than 12 years. Additionally, maintaining the osteoperiosteal hinge joint on the medial side is critical in this technique, as loss of this hinge during healing, may lead to under-correction and recurrence of the deformity.

The step-cut and reverse step-cut techniques are also popular techniques and have advantages of increased surface area and inherent stability of step-cut.[11][12][13]

Multiplanar osteotomy can correct the rotational component of cubitus varus deformity. However, this is a technically challenging procedure. Preoperative planning is more intensive and may require a CT scan to generate a 3-dimensional model of both the affected and unaffected arms.

The dome osteotomy is considered a technically challenging procedure.[14] However, this method avoids lateral condylar prominence. It can also be performed through a muscle-sparing paratricipital approach, thereby minimizing post-operative stiffness. The osteotomy is performed with convexity towards the proximal shaft. The distal segment is then rotated to achieve the desired correction.

Uneventful healing is common due to the large surface area of the osteotomy. However, rotating the distal fragment is challenging. Additionally, this can lead to stretching of the ulnar nerve. A recent modification double-dome osteotomy’ was proposed for easier rotation correction from the center of the deformity, without stretching of the neural structures.[15] Like the multiplanar osteotomy, this procedure has the benefit of addressing the rotational component of cubitus varus. Complications with this technique include transient radial nerve palsy and overcorrection.(B2)

Distraction osteogenesis is a technique that forms bone through controlled stretching of the osteotomy site slowly over time using traction. This method was performed on the ulna for the treatment of cubitus varus. Compared to other osteotomy techniques, distraction osteogenesis has consistently low rates of loss of correction.[4][16](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The cubitus varus usually occurs as a consequence of malunited supracondylar fractures. The differential includes varus deformity occurring as a result of previous fractures involving lateral condyle, trochlear osteonecrosis, distal humerus physis injury.

Treatment Planning

The planning of corrective osteotomy includes full-length radiographs of bilateral upper limbs, recording of clinical and radiological parameters, and calculation of the correction angle. The paper tracing is required to prepare a template for the osteotomy.

Prognosis

The cubitus varus, if left untreated, doesn't cause functional loss. The prime indication for corrective osteotomy is cosmesis. However, surgery is necessary in the cases having longstanding deformity with additional clinical symptoms of instability and ulnar neuropathy.

Complications

Complication rates for these procedures are reportedly as high as 15%, including radial and ulnar nerve injures, lateral condylar prominence, infection, stiffness, scarring, and under- or overcorrection. The vast majority (approximately 75%) of nerve inures are reported to be transient and were associated with the posterior approach.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The postoperative care varies depending upon the corrective procedure undertaken. The posterior above-elbow splint is given for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by an active range of motion exercises. The K wires are removed after 4 to 6 weeks depending upon the healing status.

Consultations

The follow-up also varies according to the type of osteotomy procedure and type of fixation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The prime indication for osteotomy in cubitus varus is cosmesis. The function of the limb is either minimally or not affected. The surgery is advisable in patients having symptoms of instability and ulnar nerve paresis.

Pearls and Other Issues

- The cubitus varus is a complication of malunited supracondylar fracture.

- The deformity is triplanar consisting of varus, hyperextension, and internal rotation component.

- The prime indication for surgery is a cosmetic concern, while other indications include symptoms of instability and ulnar nerve involvement.

- The corrective osteotomy techniques include lateral closing wedge, dome, double dome step cut, and reverse step cut.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The treatment of cubitus varus is teamwork involving a pediatric orthopedist, radiologist, and physiotherapist. The orthopedic surgeons are the primary care providers, and they should be aware of the commonly done corrective osteotomy procedures. The radiologist helps in better evaluation of deformity parameters. The nursing staff of orthopedics specialty also plays an important role. The physiotherapists help in regaining range of motion postoperatively.

Media

References

Ho CA. Cubitus Varus-It's More Than Just a Crooked Arm! Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2017 Sep:37 Suppl 2():S37-S41. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001025. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28799993]

Verka PS, Kejariwal U, Singh B. Management of Cubitus Varus Deformity in Children by Closed Dome Osteotomy. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017 Mar:11(3):RC08-RC12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24345.9551. Epub 2017 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28511466]

Orbach H, Rozen N, Rubin G, Dujovny E, Bor N. Outcomes of French's Corrective Osteotomy of the Humerus for Cubitus Varus Deformity in Children. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2018 Jul:20(7):442-445 [PubMed PMID: 30109795]

Solfelt DA, Hill BW, Anderson CP, Cole PA. Supracondylar osteotomy for the treatment of cubitus varus in children: a systematic review. The bone & joint journal. 2014 May:96-B(5):691-700. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B5.32296. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24788507]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNoonan KJ, Jones JW. Recurrent supracondylar humerus fracture following prior malunion. The Iowa orthopaedic journal. 2001:21():8-12 [PubMed PMID: 11813957]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Qattan MM, Yang Y, Kozin SH. Embryology of the upper limb. The Journal of hand surgery. 2009 Sep:34(7):1340-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.06.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19700076]

Card RK, Lowe JB. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Elbow Joint. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422543]

Marashi Nejad SA, Mehdi Nasab SA, Baianfar M. Effect of supination versus pronation in the non-operative treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. Archives of trauma research. 2013 Spring:2(1):26-9. doi: 10.5812/atr.10570. Epub 2013 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 24396786]

Wong HK, Lee EH, Balasubramaniam P. The lateral condylar prominence. A complication of supracondylar osteotomy for cubitus varus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1990 Sep:72(5):859-61 [PubMed PMID: 2211772]

Raney EM, Thielen Z, Gregory S, Sobralske M. Complications of supracondylar osteotomies for cubitus varus. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2012 Apr-May:32(3):232-40. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3182471d3f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22411326]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeRosa GP, Graziano GP. A new osteotomy for cubitus varus. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1988 Nov:(236):160-5 [PubMed PMID: 3052975]

Yun YH, Shin SJ, Moon JG. Reverse V osteotomy of the distal humerus for the correction of cubitus varus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2007 Apr:89(4):527-31 [PubMed PMID: 17463124]

Vashisht S, Sudesh P, Gopinathan NR, Kumar D, Karthick SR, Goni V. Results of the modified reverse step-cut osteotomy in paediatric cubitus varus. International orthopaedics. 2020 Jul:44(7):1417-1426. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04648-0. Epub 2020 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 32458036]

Banerjee S, Sabui KK, Mondal J, Raj SJ, Pal DK. Corrective dome osteotomy using the paratricipital (triceps-sparing) approach for cubitus varus deformity in children. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2012 Jun:32(4):385-93. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318255e309. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22584840]

Eamsobhana P, Kaewpornsawan K. Double dome osteotomy for the treatment of cubitus varus in children. International orthopaedics. 2013 Apr:37(4):641-6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1815-7. Epub 2013 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 23404412]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSrivastava AK, Srivastava D, Gaur S. Lateral closed wedge osteotomy for cubitus varus deformity. Indian journal of orthopaedics. 2008 Oct:42(4):466-70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.43397. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19753237]