Introduction

Human embryogenesis is a complicated process by which a fertilized egg develops into an embryo. During the first eight weeks of development, the conceptus shifts from a single-celled zygote into a multi-layered, multi-dimensional fetus with primitively functioning organs. The continued growth and increased intra-embryonic complexity during the first eight weeks of development are highly dependent upon cell signaling, proliferation, and differentiation. Due to the intricacies involved, the development of the human embryo is divided into developmental events by week. Week 1 is a major part of the germinal stage of development, a period of time that continues from fertilization through uterine implantation. Important events that occur during the first week of human embryonic development include gamete approximation, contact and fusion of gametes, fertilization, mitotic cleavage of the blastomere, morula formation, blastocyst formation, and implantation of the blastocyst.

Development

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Development

Approximately two to five million spermatozoa are deposited into the vagina during sexual intercourse and travel through the fallopian tube for potential fertilization. The lifespan of an individual sperm within the female reproductive tract ranges from three to seven days. Sperms can not repair themselves upon damage in harsh environments as they are terminally differentiated cells that lack transcription and translation machinery. They are subjected to physical stresses due to ejaculation, contractions of the female tract, alteration in the pH environment, mucous secretions, defenses of the female immune system, and must navigate a double tract fallopian tube system. Thus, of the millions of sperms inseminated at coitus, only a few thousand reach the fallopian tubes to fertilize the secondary oocyte. In contrast, the female ovary typically releases only a single matured oocyte that has halted in metaphase of meiosis II into the fallopian fimbriae.

Gamete Approximation: Fertilization requires that the sex cells are close enough in proximity to bind to one another; thus, both a sperm and an oocyte must travel from their original deposition location to approach each other within the fallopian tube. After spermatozoan deposition, uterine contraction is stimulated by prostaglandins in the semen and oxytocin released during the coital reflex. The mixture of sperms with the secretion of uterine glands is passively aspirated into the uterine cavity. It should be noted that the active motility of sperms does not aid this process, but their motility is of utmost importance in transport from the uterine cavity to the oocyte. Most sperms die within 24 hours of their release, as they are gradually reduced in number by barriers provided by abrupt constrictions at the cervix and uterine ostium. Of the hundreds of millions of sperms emitted at a single ejaculation, only 1% enter the uterus, and a trip from the cervix to the oviduct takes between 30 minutes to 6 days. In contrast, the oocyte travels via ciliary beats and rhythmical contractions of the musculature of uterine tubes. Eventually, and typically, the sperms and ova both reach the ampulla of the fallopian tube.

Contact and Fusion of Gametes: Out of the thousand or fewer sperms reaching the ovum, only one fully penetrates the oocyte to produce an embryo. The remaining sperms are engaged in the disintegration of the three barriers around the secondary oocyte by an enzyme, hyaluronidase, which is present in the acrosomal cap of sperms. The three barriers around the secondary oocyte are the corona radiata, zona pellucida, and vitelline membrane. Nevertheless, before the actual fertilization (penetration) occurs, the spermatozoa must undergo a process called capacitation, followed by an acrosomal reaction (discussed in the Cellular Section). These two processes help a sperm acquire the capability to penetrate the ovum.[1]

Once the sperm penetrates the ovum, the cytoplasm of the mature ovum contains two pronuclei: a male pronucleus composed of a sperm head with its nuclear envelope and a female pronucleus composed of the nucleus of a mature ovum. Both pronuclei contain 1N haploid chromosomes (23 chromosomes). The pronuclear envelopes disappear, and the chromosomes of each arrange themselves in the equatorial plane in order to prepare for fusion.

Fertilization: Fertilization is the process of fusing a mature male gamete and a mature female gamete to form a single cell, the zygote. The male gamete, a sperm, and the female gamete, an ovum, are both haploid and contain 23 chromosomes.[2] As the end result of gamete fusion, a zygote is diploid with 23 pairs of chromosomes (46 chromosomes). Fertilization usually occurs in the ampullary part of the fallopian (uterine) tube.

Mitotic Cleavage of the Blastomere: After fertilization, the resulting one-celled zygote will rapidly undergo multiple mitotic cleaves as it travels around four days to reach the uterine cavity. The zygote is much larger than most cells of the body and is actually visible to the naked eye. The process of cleavage or segmentation results in the production of blastomeres, which restores the standard size of cells by a progressive reduction of the cytoplasmic volume of the zygote. Once cleavage begins, the concepts will go through a two-cell stage (approximately day one of cleavage), four-cell stage (approximately day two of cleavage), twelve-cell stage (approximately day three of cleavage), and sixteen-cell stage (approximately day four of cleavage). Despite rapid increases in the number of cells during cleavage, the conceptus remains a similar size and form due to the compaction of its cells.

Morula Formation: The morula appears approximately four days after fertilization and first appears as a 16- to 32-celled mass still surrounded by the zona pellucida. Medically, this is often known as the final stage before the formation of a fluid-filled cavity within the conceptus called the blastocoel cavity, which precedes blastula formation. Recent time-lapse microscopy observations suggest that compaction may represent an important checkpoint for human embryo viability, through which chromosomally abnormal blastomeres are sensed and eliminated by the embryo. Compaction is critical because it sets anatomical differences between cells (inner versus outer), ultimately determining their fate. The group of cells present in the center of the morula will eventually give rise to the inner cell mass and the embryo proper.[3] The cells at the periphery, the outer cell mass cells, are critical in the cavitation of the morula that occurs as it transitions into a blastocyst.

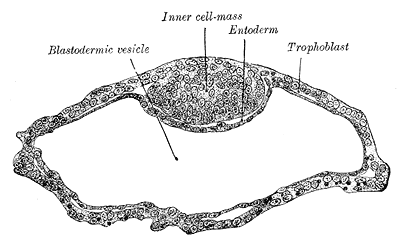

Blastocyst Formation: By the blastocyst stage (approximately day five after fertilization), the embryo has reached 50 to 150 cells and starts to strain at the confines of the zona pellucida. This is due to cell division but also active pumping of fluid by outer cell mass cells into the inner space of the blastocyst, which forms a cavity or blastocoel. The filling of this space with fluid expands the blastocyst; thus, the term expanded blastocyst. Before the creation of this fluid space, the embryo is referred to as non-expanded. Expansion functions to thin and eventually rupture the zona pellucida to permit the blastocyst to hatch from the zona pellucida. Blastocyst expansion also functions to allow a large amount of fluid entering the space to shift a grouping of cells off to one side of the hollowed interior. This cellular mass is a grouping of embryonic stem cells with unrestricted developmental potential termed the inner cell mass (ICM) within the blastocyst. The ICM has the cells that will give rise to actual fetal cells. The other cells that surround and protect the ICM and that line the inner side of the zona pellucida are the trophectoderm cells, which give rise to the fetal part of the placenta. Thus, hallmarks of successful blastocyst formation are the fluid-filled blastocoele, the ICM, and the fully differentiated trophectoderm-derived trophoblast.

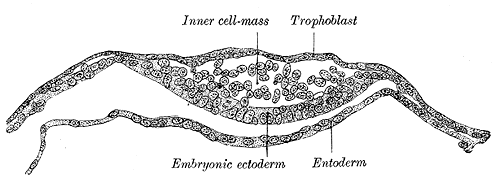

Apposition of the Blastocyst: Implantation is the process of the blastocyst embedding into the endometrial lining of the uterus, which typically occurs in Week 2 of development. For implantation to occur, the blastocyst must completely hatch from the zona pellucida once the conceptus enters the uterine cavity. Early zona pellucida disappearance can lead to tubal pregnancies. Usually, the human blastocyst implants in the endometrium near the fundus along the anterior or posterior wall of the uterus between the openings of the glands.[4][5] If implantation is too low, it can lead to placenta previa.[6] At the time of implantation, the uterus has been primed for implantation through decidualization. The uterus is in the secretory phase, which is defined by high levels of estrogen and progesterone that function to coil glands and arteries, allowing the tissue to become succulent.[7] Early implantation initiates by the apposition, or approaching, of the blastocyst to the uterine wall via cell adhesion factors and polarity signaling. The blastocyst orients with the ICM to enter the uterine lining first. Immediately prior to implantation, the outer trophoblast cells begin to differentiate to allow full implantation to proceed into Week 2 of development.

Cellular

Gamete Approximation: Gamete approximation occurs via anatomical movements of the oocyte and sperm toward the ampulla of the fallopian tube. Additionally, approximation requires chemotactic events where the oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells release chemical attractants into the local environment to which only capacitated sperms can respond. The secondary oocyte, itself, and the cumulus cells release progesterone and other nonpeptide signaling molecules. As mentioned, only spermatozoa that have undergone capacitation events are guided by chemoattractants released by the ovum environment. Capacitation is a set of physiological and biochemical changes (see details in the Biochemical Section) that initiate after moving through the cervical mucus and finalize in the fallopian tube. Capacitation renders the sperm capable of fertilizing an oocyte by modifying the head and tail of the sperm. After capacitation and before the approach to the oocyte, the sperm must also undergo an acrosomal reaction. The acrosomal reaction only occurs in capacitated sperm and is a set of changes to the acrosome, which is a Golgi-derived organelle located between the cell membrane and nuclear envelope. Generally, the acrosomal vesicle fuses with the plasma membrane to exocytose substances, mainly enzymes that facilitate fertilization by degrading the oocyte's corona radiata, zona pellucida, and vitelline membrane.

Oocyte Contact and Fusion of Gametes: The cumulus oophorus is a layer of loosely packed follicle cells connected by hyaluronic acid. As the sperm approaches the oocyte, the cells of the cumulus oophorus and corona radiata surrounding the oocyte are moved by the liberation of hyaluronidase from the acrosomal cap of the sperm to enzymatically dissolve the hyaluronic acid and expose the zona pellucida. As a second barrier, the zona pellucida is a thick striated membrane made up of three glycoproteins, ZP1, ZP2, and ZP3, that are synthesized by the oocyte.[8] The sperm head binds to ZP3 and ZP2 receptors and induces an acrosome reaction to release the acrosin enzyme, which digests zona pellucida. Now the sperm head fuses with a vitelline membrane, which acts as the third barrier. The two disintegrin peptides of the sperm head open a gateway for a single sperm to enter the oocyte cytoplasm.

Upon the entrance of the single sperm, a series of cellular events termed cortical reaction transpires to generate an impermeable zona pellucida and prevents polyspermy. Cortical granules are released and secrete serine proteases, peroxidases, and glycosaminoglycans to cut protein connections to remove receptors, harden the vitelline envelope, and attract water into the perivitelline space. This generates a gap to form the hyaline layer.

A key signaling event resulting from the binding of a sperm to its ZP receptor in the zona pellucida is an increase in the level of cytosolic Ca within the egg. Increased calcium is needed to direct the cortical reaction and also to complete fertilization.

Fertilization: The process of fertilization gives rise to five critical cellular events:

- The completion of meiosis II within the female gamete is directed by calcium-induced activation of the anaphase-promoting complex.

- There will be a restoration of a diploid number of chromosomes in the zygote.

- The determination of chromosomal sex is now complete.

- The sperm entry point may localized polarity to the determination of early axis formation.[9]

- Finally, there is an initiation of the cleavage of the zygote.

Mitotic Cleavage of the Blastomeres: Early cleavage events are synchronous and driven by maternal RNA and protein instruction until the eight-celled stage is complete. Upon the production of eight blastomeres, the cells show increased adherence via tight junctions and are totipotent with functional apparatus, which displays cell autonomy. The rapid rate of blastomeric division initiates via changes in the cell cycle, specifically the upregulation of cyclins. In IVF studies, the length and timing of the cell cycle have been shown to be one of the most important determinants in conceptus survivability.

Morula Formation: Dynamic cellular processes, such as filopodia formation and cytoskeleton-mediated cell-to-cell interactions, intervene to allow cell compaction and blastocoel formation. Compaction is driven by E-cadherins and Ca2+-driven signal transduction to instruct cell boundaries to disappear. Cell boundaries then progressively disappear until the embryo is fully compacted. Finally, at the late compaction stage, the cell boundaries reappear, the number of blastomeres increases, and the cavitation begins. At the same time that cell boundaries are reappearing, the differential orientation of cleavage planes, cell polarity, and physical forces interact and cooperate to position blastomeres either internally or externally, thereby influencing their cellular fate. Cells of the outer cell mass upregulate Na+ transporters, actively pumping Na+ into the interior space of the morula. Via osmosis, water actively follows the increased Na+ gradient, thus creating the sizeable fluid-filled cavity called the blastocoel.

Blastocyst Formation: One of the first key developmental patterning processes in the morula to blastocyst transition is to determine what becomes inner cell mass vs. trophectoderm. Studies in mice indicate that the upregulation of the transcription factors such as Oct 4, FGF, Nanog define pluripotent stem cells of the ICM, with trophectoderm cells upregulating Cdx-2 Eomes and Tead 4.

Apposition of the Blastocyst: Literature indicates that chemokines are involved in the apposition of the blastocyst to the correct location within the uterine lining for implantation. The interleukin family of signaling factors, along with leptin, IGF, and DKK-1, have all been implicated in early implantation events.

Biochemical

Capacitation: The process of fertilization is preceded by significant biochemical and physiological changes in the sperm, termed capacitation. The reactions occur in the female reproductive tract, which further facilitates the acrosome reaction. At the physiological level, capacitation involves two signaling events: fast and slow events. The fast events are the vigorous and incoherent movement of the sperm flagella, while the slow events are the discrete modulations in the sperm mobility patterns, termed hyperactivation. Another essential feature of capacitation is signaling through the protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Capacitation initiates by a series of signaling events involving the phosphorylation of phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase (PI3K) through protein kinase A (PKA) dependent cascades leading to its activation. PI3K is downregulated by protein kinase C-α (PKCα).

PI3K inactivation is necessary at the beginning of capacitation. However, as capacitation proceeds, PI3K is activated by the degradation of PKCα and PP1γ2. The activation of PKCα depends on the concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) produced by the bicarbonate-dependent soluble adenylyl cyclase. Another significant biochemical change is the removal of cholesterol from the plasma membrane of the sperm head as a feature of slow events of capacitation. This removal increases the permeability of the sperm towards calcium and bicarbonate ions, which hyperpolarizes the plasma membrane. Hyperpolarization is central to the modulation of protein phosphorylation and protein kinase activities. This activation of PKA causes PI3K activation and hence leads to an increase in actin polymerization. PI3K activation is essential for the development of hyperactivated motility of sperms necessary for successful fertilization. PKCα is active at the beginning of capacitation, resulting in PI3K inactivation. During capacitation, PKCα and PP1γ2 are degraded by a PKA-dependent mechanism, allowing the activation of PI3K.[10]

Acrosome Reaction: The second prerequisite essential to fertilization of a sperm with an oocyte is the acrosome reaction. The membrane surrounding the acrosome dissolves to fuse with the plasma membrane of the sperm's head, thus releasing the contents of the acrosome. These contents consist of surface antigens necessary for binding to the cell membrane of the egg and lytic enzymes for breaking inside the egg's tough layers for fertilization to occur. The process is facilitated by the influx of calcium and is entirely dependent on increased intracellular calcium.

The acrosome reaction is an exocytotic mechanism that releases soluble lysins of the acrosome. This release helps in developing a path in the egg coat, allowing penetration. The lysins are similar to the enzymatic content that includes acrosin, acrogranin, hyaluronidase, usually present as a part of lysosome and peroxisomes.[11] Acrosin is the major protease present in a mature sperm acrosome. It is stored in its precursor form, proacrosin, and is released onto the zona pellucida upon stimulation. The zymogen, proacrosin, is then processed into its active form, β-acrosin. This causes the lysis of the zona pellucida, thus facilitating the entry of the sperm through the innermost glycoprotein layers of the ovum.[12] Protein C inhibitors are instrumental in the regulation of acrosin. These inhibitors are present in the male reproductive tract at higher concentrations than in the blood plasma and function to inhibit the proteolytic activity of acrosin. This provides a protective role in the case of premature release or degeneration of the spermatozoa within the male reproductive tract.[13]

Many ligands, especially hormones from the female reproductive tract, are demonstrated to modulate the acrosome reaction through receptor binding. These compounds can be either activating or inhibitory to the acrosome reaction. Progesterone, catecholamines, insulin, leptin, prolactin, and angiotensin are among the inducers, while oestradiol and epidermal growth factors can inhibit acrosome reaction. Interestingly, gamma-aminobutyric acid, an inhibitor of the central nervous system, acts as an activator of the acrosome reaction. The female hormone progesterone acts by inhibiting the acrosome reaction, possibly due to the increase in cytoplasmic protein phosphorylation through the modulation of intracellular calcium concentration. However, a decrease in plasma membrane cholesterol probably determines the extent of the response of progesterone to human sperms.[14]

Clinical Significance

A hydatidiform mole is a type of gestational trophoblastic disease resulting from abnormal fertilization of an oocyte. This occurs when a sperm fertilizes an egg lacking the female pronucleus, leading to trophoblastic proliferation without any proliferation of the embryoblast or embryo proper. The cells of the trophoblast continue to function normally by secreting human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which will trigger a positive pregnancy test. A hydatidiform mole is often attributed to maternal gene defects and is more common in women 36 to 44 years of age with a history of gestational viability issues. The clinical presentation is often very vague, including possible uterine enlargement more than expected for the gestational age, vaginal spotting, severe nausea, and vomiting. Hydatidiform moles are detected via ultrasound examination and they present with normal placental development, a mass of tissue with no apparent fetal features, and the absence of heart sounds.[15][16]

Ectopic pregnancies are defined as pregnancies in which implantation occurs outside of the uterus.[17] The leading cause of ectopic pregnancy is the early disappearance of the zona pellucida allowing for opposition and attachment to occur in various anatomical locations. Other causes include pelvic inflammatory diseases (PID), scarring of the female reproductive tract, tubal defects, and so forth. Ectopic pregnancies classify into many types depending on the site of implantation. These include:

- Ampullary region of the fallopian tube: Typically, fertilization occurs in the most dilated part of the uterine tube, the ampulla. Once fertilization takes, the zygote will generally travel to the uterine cavity and implant in the wall of the uterus near the fundus. In some cases, the zygote does not travel to the uterine cavity but stays at the site of fertilization, attaches to the wall of the ampulla, and starts growing within it. Attachment to the fallopian tube is the most common abnormal implantation site, approximating almost 70% to 80% of ectopic implantation sites.[18]

- Tubal implantation: In this condition, the zygote implants in another part of the uterine tube other than the ampulla. The non-ampullary segment of the uterine tube is the second most common abnormal implantation site, approximating 12% of ectopic pregnancies.[19]

- Within the abdominal cavity: In certain rare instances, the zygote travels in the opposite direction within the fallopian tube and ultimately exits the fallopian tube to enter the abdominal cavity. The conceptus may implant at any of a number of sites in the abdomen, including in the pouch of Douglas, on the spleen or liver, in the greater omentum, or retroperitoneally. Approximately 1.3% of ectopic pregnancies implant at a site within the abdominal cavity.[20]

- Interstitial implantation: Approximately 4% of ectopic pregnancies implant in the narrowest part of the uterine tube, the interstitial segment within the muscular wall of the uterus. These ectopic pregnancies typically present with excessive maternal hemorrhage. Thus, mortality and morbidity are 7% higher in interstitial implantation than in all other types of ectopic pregnancies.[20]

- Cervical pregnancy (Internal os): In almost 0.2% of ectopic pregnancies, the zygote travels too far and actually implants at the internal os of the cervix. Embryonic growth induces pain as the cervix has minimal capacity to dilate.[21]

- Ovarian implantation (0.2%): In ovarian ectopic pregnancies, the zygote travels in the opposite direction from the uterus and implants in the ovary. This occurs in almost 0.2% of ectopic pregnancy cases.[22]

Generally, ectopic pregnancies are identified very early but can be life-threatening if detected too late. Treatment depends on the site of implantation and often requires administration of methotrexate to end the pregnancy or surgical intervention to remove the conceptus.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

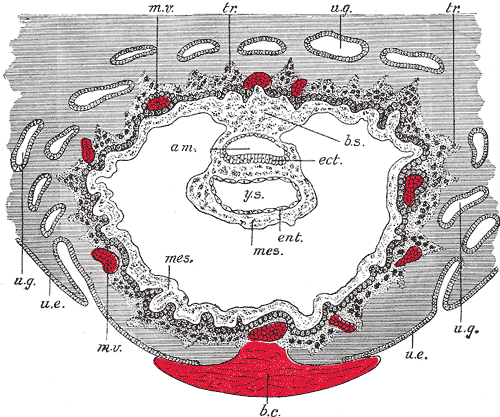

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Development of the Fetal Membranes and Placenta, Section through ovum imbedded in the uterine decidua. Semi Diagrammatic, Amniotic Cavity, Blood clot, Body stalk, Embryonic Ectoderm, Entoderm, Mesoderm, Maternal vessels, Trophoblast, Uterine epithelium, Uterine Glands, Yolk sac

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

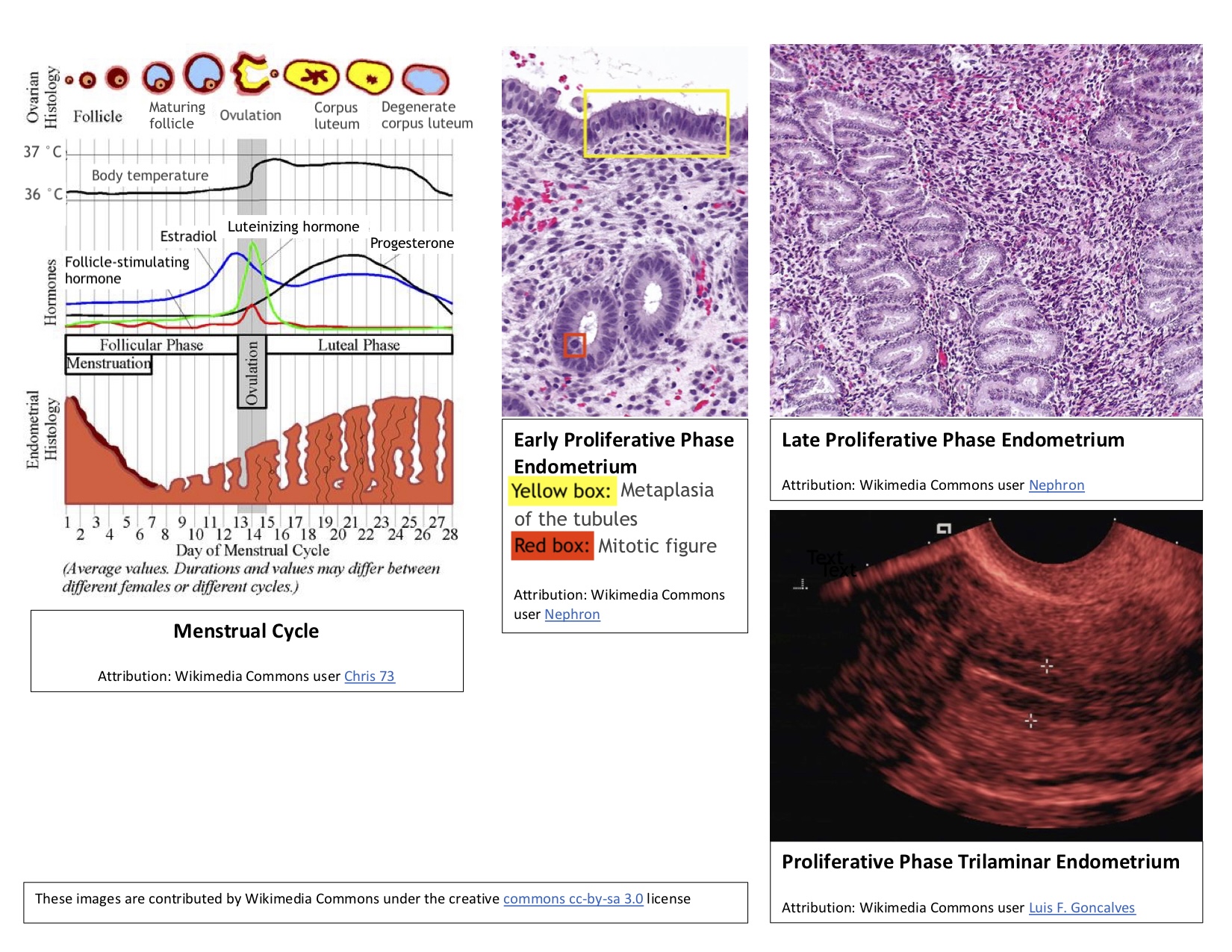

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Proliferative Phase Endometrium During the Menstrual Cycle. The follicular phase of the menstrual cycle involves the maturation of ovarian follicles, preparing one for release during ovulation. Concurrently, changes occur in the endometrium, which is why this phase is also referred to as the proliferative phase.

Nephron, Chris 73, Luis F Goncalves, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

References

Stival C, Puga Molina Ldel C, Paudel B, Buffone MG, Visconti PE, Krapf D. Sperm Capacitation and Acrosome Reaction in Mammalian Sperm. Advances in anatomy, embryology, and cell biology. 2016:220():93-106. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-30567-7_5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27194351]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKawamura N. Fertilization and the first cleavage mitosis in insects. Development, growth & differentiation. 2001 Aug:43(4):343-9 [PubMed PMID: 11473541]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCoticchio G, Lagalla C, Sturmey R, Pennetta F, Borini A. The enigmatic morula: mechanisms of development, cell fate determination, self-correction and implications for ART. Human reproduction update. 2019 Jul 1:25(4):422-438. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30855681]

Kim SM, Kim JS. A Review of Mechanisms of Implantation. Development & reproduction. 2017 Dec:21(4):351-359. doi: 10.12717/DR.2017.21.4.351. Epub 2017 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 29359200]

Zia S. Placental location and pregnancy outcome. Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association. 2013:14(4):190-3. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2013.92609. Epub 2013 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 24592104]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAbduljabbar HS, Bahkali NM, Al-Basri SF, Al Hachim E, Shoudary IH, Dause WR, Mira MY, Khojah M. Placenta previa. A 13 years experience at a tertiary care center in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi medical journal. 2016 Jul:37(7):762-6. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.7.13259. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27381536]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Reed BG, Carr BR. The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25905282]

Wassarman PM. Zona pellucida glycoproteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008 Sep 5:283(36):24285-9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800027200. Epub 2008 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 18539589]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWeber RJ, Pedersen RA, Wianny F, Evans MJ, Zernicka-Goetz M. Polarity of the mouse embryo is anticipated before implantation. Development (Cambridge, England). 1999 Dec:126(24):5591-8 [PubMed PMID: 10572036]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIckowicz D, Finkelstein M, Breitbart H. Mechanism of sperm capacitation and the acrosome reaction: role of protein kinases. Asian journal of andrology. 2012 Nov:14(6):816-21. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.81. Epub 2012 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 23001443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoreno RD, Alvarado CP. The mammalian acrosome as a secretory lysosome: new and old evidence. Molecular reproduction and development. 2006 Nov:73(11):1430-4 [PubMed PMID: 16894549]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiller DJ, Gong X, Shur BD. Sperm require beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase to penetrate through the egg zona pellucida. Development (Cambridge, England). 1993 Aug:118(4):1279-89 [PubMed PMID: 8269854]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLaurell M, Christensson A, Abrahamsson PA, Stenflo J, Lilja H. Protein C inhibitor in human body fluids. Seminal plasma is rich in inhibitor antigen deriving from cells throughout the male reproductive system. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1992 Apr:89(4):1094-101 [PubMed PMID: 1372913]

Cross NL, Razy-Faulkner P. Control of human sperm intracellular pH by cholesterol and its relationship to the response of the acrosome to progesterone. Biology of reproduction. 1997 May:56(5):1169-74 [PubMed PMID: 9160715]

Candelier JJ. The hydatidiform mole. Cell adhesion & migration. 2016 Mar 3:10(1-2):226-35. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1093275. Epub 2015 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 26421650]

Digiulio M, Wiedaseck S, Monchek R. Understanding hydatidiform mole. MCN. The American journal of maternal child nursing. 2012 Jan-Feb:37(1):30-4. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e31823853c4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22157338]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSivalingam VN, Duncan WC, Kirk E, Shephard LA, Horne AW. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. The journal of family planning and reproductive health care. 2011 Oct:37(4):231-40. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2011-0073. Epub 2011 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 21727242]

Condic ML, Harrison D. Treatment of an Ectopic Pregnancy: An Ethical Reanalysis. The Linacre quarterly. 2018 Aug:85(3):241-251. doi: 10.1177/0024363918782417. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 30275609]

Mroueh J, Margono F, Feinkind L. Tubal pregnancy associated with ampullary tubal leiomyoma. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1993 May:81(5 ( Pt 2)):880-2 [PubMed PMID: 8469506]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMummert T, Gnugnoli DM. Ectopic Pregnancy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969682]

Samal SK, Rathod S. Cervical ectopic pregnancy. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine. 2015 Jan-Jun:6(1):257-60. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.149221. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25810679]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBirge O, Erkan MM, Ozbey EG, Arslan D. Medical management of an ovarian ectopic pregnancy: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2015 Dec 20:9():290. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0774-6. Epub 2015 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 26687032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence