Introduction

Low back pain is among the most prevalent musculoskeletal complaints in clinical practice. Low back pain ranks as one of the primary causes of disability in individuals aged 45 and younger in the developed world, trailing closely behind the common cold as the second most common reason for work absenteeism.[1] Furthermore, low back pain imposes significant annual healthcare costs on society. Although epidemiological studies may vary, the incidence of low back pain is estimated to exceed 5%, with a lifetime prevalence ranging from 60% to 90%.[2] Fortunately, many instances of low back pain are self-limited and are resolved without medical intervention. Roughly half of cases resolve within 1 to 2 weeks, with 90% resolving within 6 to 12 weeks. Given the wide array of potential causes, the broad spectrum of differential diagnoses for low back pain should include consideration of lumbosacral radiculopathy.

Lumbosacral radiculopathy refers to a pain syndrome characterized by the compression or irritation of nerve roots in the lumbosacral region of the spine. This compression often stems from degenerative changes such as disc herniation, ligamentum flavum alterations, facet hypertrophy, and spondylolisthesis, culminating in the compression of one or more lumbosacral nerve roots. Symptoms typically include low back pain radiating into the lower extremities in a dermatomal pattern corresponding to the affected nerve root. Additional symptoms may include numbness, weakness, and loss of reflexes, although the absence of these symptoms does not exclude the diagnosis of lumbosacral radiculopathy.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The noxious stimulus of a spinal nerve root creates ectopic nerve signals that are perceived as pain, numbness, and tingling along the nerve distribution, as well as weakness in the nerve root's myotome distribution when severe enough. Lesions of the intervertebral discs and degenerative disease of the spine are the most common causes of lumbosacral radiculopathy. In the degenerative setting, the intervertebral disc undergoes desiccation and fibrosis, then fissuring or tearing, which results in an increased risk of herniation of disc material outside of the normal confines of the disc space. Disc herniations may compress one or more nerve roots, producing lumbosacral radiculopathy. In severe cases with a large disc herniation that compresses multiple nerve roots, patients may present with cauda equina syndrome.[4] In addition to degenerative etiology, any process irritating spinal nerve roots can result in lumbosacral radiculopathy.

Epidemiology

The lifetime prevalence rates of low back pain within the general population range from 60% to 90%, of which 5% to 10% will suffer from radiculopathy.[2][5] The condition constitutes a significant reason for patient referral to neurologists, neurosurgeons, or orthopedic spine surgeons. Low back pain is the second greatest cause of workplace absenteeism after upper respiratory tract infections. About 25 million people miss work due to low back pain, and more than 5 million are disabled from it. Patients with chronic back pain account for a significant proportion of healthcare expenditures.[3] Known risk factors for progressive lumbar degenerative changes include smoking, genetics, and repetitive trauma.[6]

Pathophysiology

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is the clinical term that describes a predictable constellation of symptoms occurring secondary to mechanical or inflammatory cycles compromising at least one of the lumbosacral nerve roots. Patients can present with radiating pain, numbness or tingling, weakness, and gait abnormalities across a spectrum of severity. Depending on the nerve root affected, patients can present with these symptoms in predictable patterns affecting the corresponding dermatome or myotome.[7]

The intervertebral disc experiences desiccation and fibrosis in the degenerative setting, leading to fissuring or tearing. This increases the risk of herniation of disc material beyond the normal confines of the disc space. The posterior longitudinal ligament is the strongest in the midline, and the posterolateral annulus fibrosus may bear a disproportionate portion of the load exerted from the weight above. This may explain why most lumbosacral disc herniations occur posterolaterally within the central canal or lateral recess. Herniated discs may compress one or more nerve roots, producing lumbosacral radiculopathy. In the lumbosacral region, herniated discs characteristically compress the traversing nerve root as they enter the lateral recess before exiting through the neural foramen of the level below. For instance, in the case of an L5-S1 disc herniation, this compression would typically affect the S1 nerve root.

History and Physical

As with any disease process, a comprehensive history and physical examination are essential for diagnosing lumbosacral radiculopathy. Pain is the most commonly reported symptom. However, patients may also experience numbness or weakness along the dermatome/myotome distribution supplied by the affected nerve root. Radicular pain is often described as "electrical shocks" or "shooting pains" that radiate along the course of the nerve root's dermatome. During history-taking, screening for any red-flag symptoms that could indicate an urgent or emergent clinical condition is essential.

Before evaluating a patient, clinicians must first rule out any associated "red-flag" symptoms, as these symptoms could indicate a more severe underlying condition that requires immediate attention. The symptoms include thoracic pain, fever/unexplained weight loss, intravenous drug use, immunosuppression, prolonged use of steroids, night sweats, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and malignancy. In addition, any previous surgeries, chemo/radiation, recent imaging, bloodwork, or history of metastatic disease should be documented. This can be seen in association with pain at night, pain at rest, unexplained weight loss, or night sweats. Significant medical comorbidities, neurologic deficit or serial exam deterioration, gait ataxia, saddle anesthesia, acute onset of urinary retention or overflow incontinence, progressive lower extremity weakness, and age of onset (bimodal; younger than 20 or older than 55) should be considered.

A full neurological examination should be performed, including assessing upper motor neuron findings (eg, Babinski sign, clonus, and spasticity). During physical examination, various maneuvers can aid clinicians in diagnosing lumbosacral radiculopathy. The Lasègue test, or straight leg test, involves passively raising one leg into the air, creating increased tension on the sciatic nerve between 30° to 60° from the exam table. While the crossed straight leg test is less sensitive, it offers greater specificity. A positive sign is noted if the patient's symptoms are reproduced during passive movement between 30° and 60°, suggesting lower lumbar nerve root involvement (L4 to S1). Similarly, the reverse straight leg (Ely) test stretches the femoral nerve and the L2 to L4 nerve roots by extending the hip and flexing the knee with the patient in a prone position. Additionally, radicular symptoms can be provoked by seating the patient with the neck in full flexion and knees in full extension (slump test).[8][9]

In the setting of lumbosacral radiculopathy, diminished deep tendon reflexes can be expected. Specifically, the knee-jerk reflex may be affected for the L4 nerve root, the medial hamstring reflex for the L5 nerve root, and the Achilles reflex for the S1 nerve root. Motor weakness associated with lumbosacral radiculopathy typically affects specific muscle groups—the quadriceps femoris (knee extension) for the L4 nerve root, the tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus (dorsiflexion) for the L5 nerve root, and the gastrocnemius (plantarflexion) for the S1 nerve root. Additionally, decreased sensation is often noted along specific dermatomes: the medial malleolus and medial foot for the L4 nerve root, the dorsum of the foot for the L5 nerve root, and the lateral malleolus and lateral foot for the S1 nerve root.

Evaluation

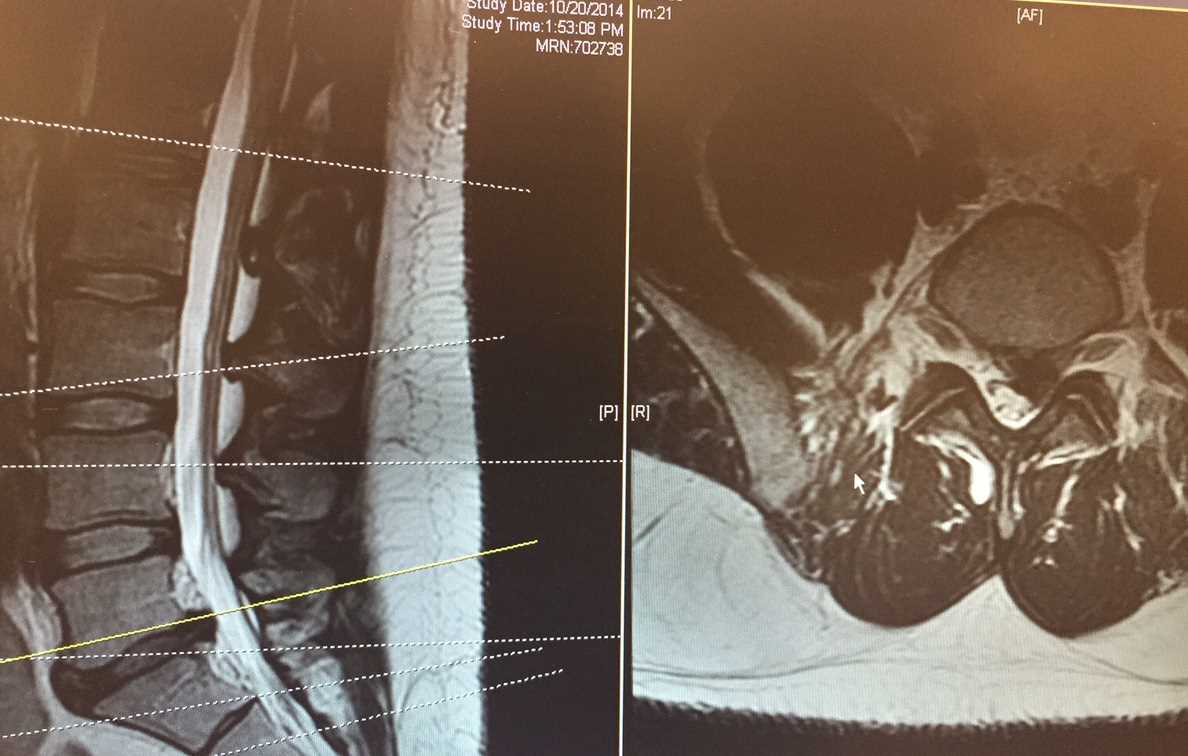

Given the favorable outcome and often spontaneous resolution of the vast majority of low back pain symptoms and lumbosacral radiculopathy, extensive imaging is usually not necessary in patients with symptoms of less than 4 to 6 weeks duration. The diagnostic process should be initiated with a comprehensive physical examination. Neurological deficits, particularly focal weakness, detected during examination warrant further investigation. If symptoms persist beyond 1 to 2 months despite conservative management, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast is considered the gold standard for evaluating lumbosacral radiculopathy. In cases where infection needs to be ruled out, MRI with contrast is recommended, especially for patients with a history of previous spinal surgeries (see Image. Lumbar MRI).

A computed tomography (CT) myelogram is an alternative option for patients who cannot undergo MRI. However, CT is not as sensitive in visualizing soft tissue or tumors and is not recommended for routine use. On the other hand, x-rays are simple and readily available in most developed countries. They can reveal gross bony abnormalities such as fractures, spondylolisthesis, disc space narrowing, and other degenerative changes. In cases where radiographic findings do not align with the patient's clinical presentation, electromyography and nerve conduction studies can help localize a lesion with relatively high diagnostic specificity.[10]

Treatment / Management

Treatment varies depending on the etiology and severity of symptoms. Conservative management of symptoms is generally considered the first-line treatment. Medications are used to manage pain symptoms, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, anti-epileptic medications that can be used to treat nerve-related pain (eg, gabapentin), and in severe cases, low-dose opiates. Systemic steroids are an option for lumbosacral radiculopathy, which can result in modest benefits.[11] (A1)

Nonpharmacological interventions are often utilized as well. Physical therapy, acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and traction are all commonly used to treat lumbosacral radiculopathy. Notably, the data supporting the use of these treatment modalities are equivocal. Interventional techniques are also commonly used and include epidural steroid injections and percutaneous disc decompression. In refractory cases, surgical decompression can be performed, in addition to instrumented fusion, if there is concern for instability.[12][13][14](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The broad spectrum of differential diagnoses for lumbosacral radiculopathy includes, but is not limited to, the following conditions:

- Degenerative conditions of the spine (most common causes):

- Spondylolisthesis: In the degenerative setting, this arises from a pathologic cascade involving intervertebral disc degeneration, subsequent intersegmental instability, and facet joint arthropathy.

- Spinal stenosis

- Adult isthmic spondylolisthesis: Typically caused by an acquired defect in the pars interarticularis. However, the degenerative subtype is more common in adults.

- Pars defects (spondylolysis) in adults are often secondary to repetitive microtrauma.

- Trauma (burst fractures with bony fragment retropulsion):

- Clinicians should recognize that spinal fractures can occur in younger, healthy patient populations secondary to high-velocity injuries, such as motor vehicle accidents and falls from height, as well as in older individuals, particularly those with osteoporosis, where low-velocity injuries or spontaneous fractures may occur.

- Associated bleeding from the injury can result in a deteriorating neurological examination.

- Benign or malignant tumors: They include metastatic tumors, which are most common, and primary tumors, including ependymoma, schwannoma, neurofibroma, lymphoma, lipomas, paraganglioma, ganglioneuroma, osteoblastoma, and multiple myeloma.

- Infections: Infections may manifest as osteodiscitis, osteomyelitis, epidural abscess, fungal infections, or additional conditions such as Lyme disease, HIV/AIDS-defining illnesses, and herpes zoster.[15]

- Vascular conditions: Vascular conditions include hemangioblastoma, vascular claudication, and arteriovenous malformations.[16]

- Inflammatory conditions: Inflammatory conditions may include trochanteric bursitis of the hip.[17]

- Peripheral conditions: Peripheral conditions may encompass neuropathy and piriformis syndrome.[18]

- Congenital conditions: Congenital conditions may involve conjoined nerve roots.

Prognosis

The majority of cases of lumbosacral radiculopathy tend to resolve with conservative management. However, for those necessitating surgical intervention, a study indicated that among 100 patients undergoing discectomy, 73% experienced complete relief of leg pain and 63% had complete relief of back pain at the 1-year follow-up.[21] These numbers remained stable at the 5- to 10-year follow-up, with 62% reporting complete relief in both categories. Notably, only 5% qualified as having failed back syndrome at the 5- to 10-year follow-up.[22]

Complications

Common complications resulting from surgical intervention for lumbosacral radiculopathy include, but are not limited to, superficial wound infection (1% to 5%),[23] increased motor deficit, unintended incidental durotomy, recurrent herniated lumbosacral disc (4% with 10-year follow-up),[24] and postoperative urinary retention.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Lumbosacral radiculopathy refers to a pain syndrome resulting from compression or irritation of nerve roots in the lumbosacral region, commonly characterized by symptoms such as low back pain, leg pain, lower extremity numbness or tingling, and weakness. Typically attributed to degenerative changes, this condition can often be managed conservatively with approaches including medications, non-pharmacological interventions such as physical therapy, and localized pain treatments such as targeted injections.

If symptoms remain refractory to conservative management, further evaluation through radiographic imaging and surgical intervention may be warranted in some instances. If an individual is experiencing symptoms suggestive of lumbosacral radiculopathy, seeking evaluation from a healthcare provider to rule out red-flag symptoms is advisable. Prompt assessment and treatment are essential for conditions associated with these symptoms.

Pearls and Other Issues

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is a prevalent complaint in clinical practice, accounting for numerous annual doctor visits. Although most cases are benign and resolve spontaneously, conservative management is the initial approach for patients lacking clinical red-flag symptoms. However, if symptoms persist despite conservative measures or if weakness or red-flag symptoms are evident, diagnostic tools such as radiographic studies, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can aid in establishing a diagnosis.[16][7][14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is a prevalent issue, and it is crucial for advanced practice providers and physicians working collaboratively to be vigilant about recognizing red-flag symptoms, which necessitates emergent interventions. Timely reporting to the physician and coordinated team management are essential for optimizing patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cunningham LS, Kelsey JL. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. American journal of public health. 1984 Jun:74(6):574-9 [PubMed PMID: 6232862]

Frymoyer JW. Back pain and sciatica. The New England journal of medicine. 1988 Feb 4:318(5):291-300 [PubMed PMID: 2961994]

Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R. The Epidemiology of low back pain. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology. 2010 Dec:24(6):769-81. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21665125]

Rider LS, Marra EM. Cauda Equina and Conus Medullaris Syndromes. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725885]

Huysmans E, Goudman L, Van Belleghem G, De Jaeger M, Moens M, Nijs J, Ickmans K, Buyl R, Vanroelen C, Putman K. Return to work following surgery for lumbar radiculopathy: a systematic review. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2018 Sep:18(9):1694-1714. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.05.030. Epub 2018 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 29800705]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShedid D, Benzel EC. Cervical spondylosis anatomy: pathophysiology and biomechanics. Neurosurgery. 2007 Jan:60(1 Supp1 1):S7-13 [PubMed PMID: 17204889]

Tarulli AW, Raynor EM. Lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurologic clinics. 2007 May:25(2):387-405 [PubMed PMID: 17445735]

van der Windt DA, Simons E, Riphagen II, Ammendolia C, Verhagen AP, Laslett M, Devillé W, Deyo RA, Bouter LM, de Vet HC, Aertgeerts B. Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010 Feb 17:(2):CD007431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007431.pub2. Epub 2010 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 20166095]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAl Nezari NH, Schneiders AG, Hendrick PA. Neurological examination of the peripheral nervous system to diagnose lumbar spinal disc herniation with suspected radiculopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013 Jun:13(6):657-74. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.02.007. Epub 2013 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 23499340]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNguyen HS, Doan N, Shabani S, Baisden J, Wolfla C, Paskoff G, Shender B, Stemper B. Upright magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine: Back pain and radiculopathy. Journal of craniovertebral junction & spine. 2016 Jan-Mar:7(1):31-7. doi: 10.4103/0974-8237.176619. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27041883]

Goldberg H, Firtch W, Tyburski M, Pressman A, Ackerson L, Hamilton L, Smith W, Carver R, Maratukulam A, Won LA, Carragee E, Avins AL. Oral steroids for acute radiculopathy due to a herniated lumbar disk: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015 May 19:313(19):1915-23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4468. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25988461]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKennedy DJ, Noh MY. The role of core stabilization in lumbosacral radiculopathy. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2011 Feb:22(1):91-103. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2010.12.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21292147]

Tang S, Mo Z, Zhang R. Acupuncture for lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupuncture in medicine : journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society. 2018 Apr:36(2):62-70. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2016-011332. Epub 2018 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 29496679]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWenger HC, Cifu AS. Treatment of Low Back Pain. JAMA. 2017 Aug 22:318(8):743-744. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9386. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28829855]

Changa AR, Jain R. Herpes zoster lumbar radiculitis. Neurology. 2020 Sep 22:95(12):552-553. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010586. Epub 2020 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 32759189]

Urits I, Burshtein A, Sharma M, Testa L, Gold PA, Orhurhu V, Viswanath O, Jones MR, Sidransky MA, Spektor B, Kaye AD. Low Back Pain, a Comprehensive Review: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Current pain and headache reports. 2019 Mar 11:23(3):23. doi: 10.1007/s11916-019-0757-1. Epub 2019 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 30854609]

Seidman AJ, Taqi M, Varacallo MA. Trochanteric Bursitis (Archived). StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860738]

Hicks BL, Lam JC, Varacallo MA. Piriformis Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846222]

Mavrogenis AF, Papagelopoulos PJ, Sapkas GS, Korres DS, Pneumaticos SG. Lumbar synovial cysts. Journal of surgical orthopaedic advances. 2012 Winter:21(4):232-6 [PubMed PMID: 23327848]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePeng H, Conermann T. Arachnoiditis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310433]

Lewis PJ, Weir BK, Broad RW, Grace MG. Long-term prospective study of lumbosacral discectomy. Journal of neurosurgery. 1987 Jul:67(1):49-53 [PubMed PMID: 3598671]

Orhurhu VJ, Chu R, Gill J. Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969599]

Shektman A, Granick MS, Solomon MP, Black P, Nair S. Management of infected laminectomy wounds. Neurosurgery. 1994 Aug:35(2):307-9; discussion 309 [PubMed PMID: 7969840]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavis RA. A long-term outcome analysis of 984 surgically treated herniated lumbar discs. Journal of neurosurgery. 1994 Mar:80(3):415-21 [PubMed PMID: 8113853]