Introduction

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the second most common retinal vascular disease and is a common loss of vision in older patients.[1] There are two types of RVO: Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). Central retinal vein occlusion is an occlusion of the main retinal vein posterior to the lamina cribrosa of the optic nerve and is typically caused by thrombosis. Central retinal vein occlusion is further divided into two categories: non-ischemic (perfused) and ischemic (nonperfused). Branch retinal vein occlusion is a blockage of one of the tributaries of the central retinal vein.

Non-ischemic CRVO is the most common, accounting for about 70% of cases. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) is often better than 20/200. The characteristics of non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion include good visual acuity, a mild or no pupillary defect, and mild visual changes. Non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion can also be referred to as partial, perfused, or venous stasis retinopathy.[2]

Ischemic CRVO can be the primary or progression of a non-ischemic CRVO, although progression is not common. Approximately half resolve without treatment or intervention. Ischemic central retinal vein occlusion has a much lower visual prognosis and accounts for about 30% of cases. Around 90% of patients with visual acuities worse than 20/200 have ischemic central retinal vein occlusion. Ischemic central retinal vein occlusion carries a poorer prognosis and is defined as having at least 10 areas of retinal capillary nonperfusion. Other names for ischemic central retinal vein occlusion include complete, nonperfused, or hemorrhagic retinopathy.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A primary risk factor for the development of central retinal vein occlusion is age, with 90% of patients older than 50 years old. Systemic arterial hypertension, open-angle glaucoma, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia have all been implicated as other primary risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Other associated risk factors include smoking, optic disc drusen, optic disc edema, hypercoagulable state (polycythemia, multiple myeloma, cryoglobulinemia, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, Leiden factor V, activated protein C resistance, hyperhomocysteinemia, Protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III mutation, prothrombin mutation), syphilis, sarcoidosis, African American race, sickle cell, HIV, vasculitis, drugs such as oral contraceptives or diuretics, abnormal platelet function, orbital disease, and rarely migraines.[4]

Any cause of reduced venous outflow, damage to the venous vasculature, or hypercoagulable states places the patient at an increased risk for central retinal vein occlusion. Vasculopathic risk factors can cause compression of the central retinal vein by the central retinal artery. The increased intraocular pressure in glaucoma can compromise retinal vein outflow and produces stasis. However, the exact etiology can be elusive in some cases.

Epidemiology

Central retinal vein occlusion is one of the main causes of sudden, painless vision loss in adults. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusions in the developed world has been found to be 5.20 per 1000, and the prevalence of central retinal vein occlusion is 0.8 per 1000.[5]

Pathophysiology

Three main factors contribute to thrombosis: venous stasis, endothelial damage, and hypercoagulability. Any condition that causes an increase in these factors can precipitate a central retinal vein occlusion.[6] Anatomically, the central retinal artery shares a common sheath of adventitia with the central retinal vein, located posterior to the lamina cribrosa at the arteriovenous crossing. Through the process of atherosclerosis, there may be compression of the vein by the artery. This can induce a central retinal vein occlusion.

History and Physical

Patients with CRVO will often describe the blurry or distorted vision in one eye that began suddenly. This vision loss will be painless. Neurological signs such as paresthesias, decreased extraocular movements, muscle weakness, slurred speech, ptosis, and increased deep tendon reflexes suggest a diagnosis other than central retinal vein occlusion.

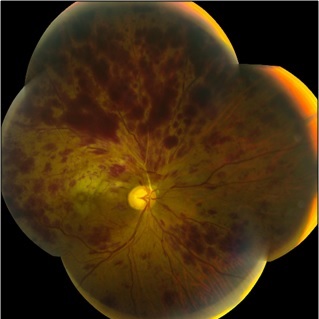

Depending on the type of CRVO, the patient may have vague complaints of visual disturbance or significantly reduced vision. Similarly, they may have a relatively normal exam or exhibit an afferent pupillary defect in the affected eye, color vision reduction, and/or a reduction in visual acuity. On examination of the ocular fundus, central retinal vein occlusions are described as a “blood and thunder” appearance, which comes from the extensive hemorrhages seen throughout the retina. Other fundus findings include cotton wool spots, damage to the retinal nerve fiber layer, and swelling of the optic disc. In non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion, an ophthalmoscopy exam typically shows tortuosity and mild dilation of the retinal veins, along with hemorrhages in all quadrants. Findings in ischemic central retinal vein occlusion typically show marked retinal edema, venous dilation, and extensive 4-quadrant hemorrhage.[7]

Evaluation

A central retinal vein occlusion requires an extensive laboratory workup to determine the cause. All patients diagnosed with a central retinal vein occlusion should get the following tests and labs:

- Blood pressure

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Complete blood count

- Random blood glucose

- Random total and HDL cholesterol

- Plasma protein electrophoresis (dysproteinemias in association with multiple myeloma)

- Urea, electrolytes, and creatinine (a renal disease in association with hypertension)

- Thyroid function tests (associated with dyslipidemia)

- EKG (left ventricular hypertrophy secondary to hypertension)

The following tests are indicated in patients either under the age of 50, with bilateral retinal vein occlusion and a history of previous thrombosis or a family history of thrombosis:[7]

- Chest x-ray (sarcoidosis, tuberculosis)

- C-reactive protein

- Thrombophilia screen (thrombin time, prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time, antithrombin functional assay, protein C, protein S, activated protein C resistance, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin G20210A mutation; anticardiolipin antibody, lupus anticoagulant)

- Autoantibodies (rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-DNA antibody)

- Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme

- Fasting plasma homocysteine level

- Treponemal serology

- Carotid duplex imaging (exclude ocular ischemic syndrome)

Treatment / Management

No totally effective medical treatment is available for either the prevention or treatment of central retinal vein occlusion. In patients with central retinal vein occlusion, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is elevated; this leads to swelling as well as new vessels (neovascularization) that are prone to bleeding. Often treatment involves intravitreal injections of an anti-VEGF drug to reduce the new blood vessel growth and swelling. The following medical treatments have been advocated with varying success:

- Aspirin

- Anti-inflammatory agents

- Isovolemic hemodilution

- Plasmapheresis

- Systemic anticoagulation

- Fibrinolytic agents

- Systemic corticosteroids

- Intravitreal injection of alteplase

- Intravitreal injection of ranibizumab[8]

- Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone

- Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab[9]

- Intravitreal injection of aflibercept[10]

- Dexamethasone intravitreal implant (A1)

Surgical interventions include laser photocoagulation, chorioretinal venous anastomosis, radial optic neurotomy, and vitrectomy.

There are specific surgical and laser approaches have been found to potentially improve visual acuity in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) can be done when central retinal vein occlusions have an associated vitreous hemorrhage. PPV may be used to clear the hemorrhage from the visual axis and allows for better visualization of the retina. A PPV may also ablate neovascularization that can cause neovascular glaucoma in the anterior segment. Laser pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) can be done to treat neovascularization, with the goal of devitalizing some of the retinal tissue to prevent further neovascularization and treat iris neovascularization. There is no evidence at this time supporting prophylactic PRP without neovascularization.[11](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of a central retinal vein occlusion include the following:[12]

- Ocular ischemic syndrome

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- Hyperviscosity retinopathy

- Branch retinal vein occlusion

Prognosis

Central retinal vein occlusion has a better prognosis in younger patients. One-third of older patients improve without treatment, one-third stay the same, and one-third get worse. If the central retinal vein occlusion does not become ischemic, return to baseline or near baseline vision occurs in about 50% of patients. Chronic macular edema is the main cause of poor vision. In most cases, the prognosis correlates with initial visual acuity.

- If visual acuity is 20/60 or better, the visual acuity is likely to remain the same.

- If the patient has 20/80-20/200 vision, the clinical course varies. Visual acuity may improve, stay the same, or worsen.

- In visual acuity worse than 20/200, improvement is unlikely.

Ischemic central retinal vein occlusion has a more variable prognosis due to macular ischemia. Patients have a high risk of neovascular glaucoma due to the development of rubeosis iris (neovascularization of the iris) in 50% of eyes, usually between 2 to 4 months. Retinal neovascularization occurs in 5% of the eyes.[3]

Complications

Central retinal vein occlusion leads to hypoxia in the retinal tissues and the subsequent release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inflammatory mediators. Complications of this include macular edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and neovascular glaucoma.[13]

Macular edema can lead to significant vision loss in patients with central retinal vein occlusion. Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections have been used to decrease edema and improve visual acuity.[14]

Iris neovascularization develops in two-thirds of cases of ischemic central retinal vein occlusion. When iris neovascularization develops, one-third of these develop neovascular glaucoma. A total of 10% of these cases occur in combination with branched retinal artery occlusion. The most important risk factors for iris neovascularization are poor visual acuity, large areas of retinal capillary nonperfusion, and intraretinal blood.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

In non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion, initial follow-up should at 3 months, although the patient should return sooner if the vision deteriorates. Patients with ischemic central retinal vein occlusion should be monitored on a monthly basis for 6 months for the development of anterior segment neovascularization or neovascular glaucoma, with gonioscopy performed at each visit prior to dilation. Patients treated with anti-VEGF agents should be observed for a similar duration after discontinuation of the drugs. Patients should be monitored for up to 2 years to assess for significant ischemia and macular edema.[15]

Consultations

The most important next step in the care of a patient with a central retinal vein occlusion is a referral to an ophthalmologist, preferably a retina specialist. Retina specialists are the only physicians qualified to perform a pars plana vitrectomy. Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections and/or PRP may also be indicated and can be performed by a retina specialist or by many general ophthalmologists.

Deterrence and Patient Education

If a patient has sudden vision loss, an immediate referral to an ophthalmologist or visit to the emergency department is warranted. It is important to educate patients that any sudden vision loss is not normal and they should consult a medical professional immediately.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Medical practitioners should take a careful history when evaluating for a central retinal vein occlusion. Any mention of the risk factors noted earlier should raise suspicion for a vein occlusion. As with any sudden loss of vision, ophthalmology should be consulted as soon as possible. CRVO is an ocular emergency and primary care clinicians should make the consult with the ophthalmologist immediately. The medical practitioner should assess visual acuity, pupil constriction, and intraocular pressure of both eyes. Treatment should be directed by ophthalmology.

After a diagnosis of a CRVO, a multitude of medical disciplines may need to be involved in the care of the patient. If the decreased vision disables the patient, physical and occupational therapy may need to get involved. Depending on the underlying cause of the CRVO, specialists including but not limited to hematology/oncology, endocrinology, obstetrics, cardiology, neurology, rheumatology, or infectious disease may need to evaluate the patient. Regardless of the etiology, the patient should regularly follow up with their ophthalmologist and primary care provider to help control risk factors and prevent future complications.[1]

The interprofessional team is composed of physicians, nurse practitioners, specialty care nurses, and pharmacists. Nurses monitor patients, provide education to patients and their families, and provide status updates to the team. Effective communication between members of the team can lower the morbidity of CRVO. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Woo SC, Lip GY, Lip PL. Associations of retinal artery occlusion and retinal vein occlusion to mortality, stroke, and myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eye (London, England). 2016 Aug:30(8):1031-8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.111. Epub 2016 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 27256303]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHayreh SS, Klugman MR, Beri M, Kimura AE, Podhajsky P. Differentiation of ischemic from non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion during the early acute phase. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 1990:228(3):201-17 [PubMed PMID: 2361592]

. Baseline and early natural history report. The Central Vein Occlusion Study. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1993 Aug:111(8):1087-95 [PubMed PMID: 7688950]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLim LL, Cheung N, Wang JJ, Islam FM, Mitchell P, Saw SM, Aung T, Wong TY. Prevalence and risk factors of retinal vein occlusion in an Asian population. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Oct:92(10):1316-9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140640. Epub 2008 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 18684751]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKlein R, Moss SE, Meuer SM, Klein BE. The 15-year cumulative incidence of retinal vein occlusion: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2008 Apr:126(4):513-8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.513. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18413521]

Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, Lim L, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Kowalski JW, Nguyen H, Wong TY, International Eye Disease Consortium. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology. 2010 Feb:117(2):313-9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20022117]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceParodi MB, Bandello F. Branch retinal vein occlusion: classification and treatment. Ophthalmologica. Journal international d'ophtalmologie. International journal of ophthalmology. Zeitschrift fur Augenheilkunde. 2009:223(5):298-305. doi: 10.1159/000213640. Epub 2009 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 19372724]

Campochiaro PA, Brown DM, Awh CC, Lee SY, Gray S, Saroj N, Murahashi WY, Rubio RG. Sustained benefits from ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: twelve-month outcomes of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2011 Oct:118(10):2041-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.02.038. Epub 2011 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 21715011]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTsai MJ, Hsieh YT, Peng YJ. Comparison between intravitreal bevacizumab and posterior sub-tenon injection of triamcinolone acetonide in macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusion. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2018:12():1229-1235. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S170562. Epub 2018 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 30013316]

Kaya F, Kocak I, Aydin A, Baybora H, Koc H, Karabela Y. Effect of aflibercept on persistent macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2018 Nov:41(9):809-813. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2018.01.024. Epub 2018 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 30361176]

. A randomized clinical trial of early panretinal photocoagulation for ischemic central vein occlusion. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group N report. Ophthalmology. 1995 Oct:102(10):1434-44 [PubMed PMID: 9097789]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMendrinos E, Machinis TG, Pournaras CJ. Ocular ischemic syndrome. Survey of ophthalmology. 2010 Jan-Feb:55(1):2-34. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.02.024. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19833366]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNicholson L, Vazquez-Alfageme C, Patrao NV, Triantafyllopolou I, Bainbridge JW, Hykin PG, Sivaprasad S. Retinal Nonperfusion in the Posterior Pole Is Associated With Increased Risk of Neovascularization in Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. American journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Oct:182():118-125. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.07.015. Epub 2017 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 28739419]

Mir TA, Kherani S, Hafiz G, Scott AW, Zimmer-Galler I, Wenick AS, Solomon S, Han I, Poon D, He L, Shah SM, Brady CJ, Meyerle C, Sodhi A, Linz MO, Sophie R, Campochiaro PA. Changes in Retinal Nonperfusion Associated with Suppression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Retinal Vein Occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2016 Mar:123(3):625-34.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.030. Epub 2015 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 26712560]

Stem MS, Talwar N, Comer GM, Stein JD. A longitudinal analysis of risk factors associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2013 Feb:120(2):362-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.080. Epub 2012 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 23177364]