Introduction

Inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is a sequence of signs and symptoms that refers to obstruction or compression of the inferior vena cava (IVC). The pathophysiology of IVCS is similar to superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) because of the presence of an underlying process that inhibits venous return to the right atrium. IVCS is not a primary diagnosis because it is often caused by other underlying pathologies.[1]

Symptoms and signs of IVCS result from a reduced venous return to the heart, as well as a pooling of blood in the IVC, which causes hypotension, tachycardia, lower extremity edema, elevated liver enzymes, end-organ failures and, hypoxia, altered mental status, and death.[2] IVCS is less frequently found in comparison with the superior vena cava syndrome.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) depends on the interrupted blood flow location. The pathogenesis of IVCS is divided into two events, including the vena cava obstruction and compression by adjacent structures. The obstruction of the IVC is mostly caused by a primary thrombotic event[1], either congenital or acquired. Congenital thrombosis of the IVC is often asymptomatic which is caused by well-developed collaterals. In contrast, acquired etiologies include spontaneous thrombosis of the vessel either due to external compression or pathological changes of the IVC wall.[1] Thrombosis of the IVC can be due to the propagation of a clot from deep venous thrombosis or from the extension of a thrombus.[1] In addition, conditions that increase the obstruction risk of IVCS are malignancy, pregnancy, infection, obesity, or other intrinsic vein disease.

Malignancies of organs near the IVC, such as renal cell carcinoma[3], gastric adenocarcinoma[4], pancreatic adenocarcinoma[5], primary or metastatic hepatic malignancies or tumor of any organ surrounding the IVC can compress the IVC which leads to obstruction of venous return to the heart. Thus, it causes venous pooling and decreases heart preload. Tumor compression results in thrombosis can sometimes lead to the development of superior vena syndrome in conjunction with IVCS.[6]

In pregnancy, the distended uterus can compress the IVC which leads to obstructing the blood flow to the heart and causes increased venous congestion or pooling.[7] Obesity may also be implicated as an etiology of IVCS. A study showed an association between increased body mass index (BMI), greater than 30 kg/meter square, with increased pressure gradients between the thoracic and abdominal vena cava[8] in patients with signs and symptoms of IVCS.

IVCS can also be due to congenital malformations such as May-Thurner syndrome or Budd-Chiari syndrome. May-Thurner syndrome is a chronic condition in which anatomical variations of vessels in the iliocaval region cause blood flow obstruction.[9] Budd-Chiari syndrome can be classified as primary or secondary. The primary classification refers to any obstruction of the hepatic vein due to a primarily venous process such as thrombosis or phlebitis. In comparison, secondary relates to compression of the hepatic veins due to external lesions such as cancer.[10]

IVCS can also be caused by iatrogenic processes such as IVC filter placement and venous catheters, which promotes thrombosis[1]. In addition, solid organ transplant or surgery, such as hepatic lobe resection can also increase the risk of thrombosis.[2] Evidence from the literature supports that other disease processes, such as cholelithiasis[11] and retroperitoneal hemorrhage.[12], can cause obstruction or compression of the IVC. Hepatic vena cava syndrome, which is associated with poor-hygiene causing bacterial infection leading to thrombophlebitis of the hepatic veins near the IVC outflow tract, is also recognized as an etiology of IVC syndrome.[13]

It has been observed that using Broviac central venous hyperalimentation catheters in pediatric children and teens who need IV therapy usually for an extended period can develop IVC syndrome.[14]

Epidemiology

Because inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is not a primary diagnosis, it is difficult to truly quantify the incidence because of different underlying pathologies. Reported IVCS shows frequencies of 4 to 15% to an association with deep vein thrombosis.[15] Case reports that have been published stated that gastric cancer, renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver pathology caused IVCS.[4][3][5][13] However, the exact incidence has never been reported.

Pathophysiology

The inferior vena cava (IVC) returns blood to the heart, along with superior vena cava (SVC). Obstruction or compression to the IVC reduces the venous return to the heart, causing an imbalance in the hemodynamic equilibrium. Decreased venous return causes hemodynamic instability in several ways. When there is a decrease in venous return, it will decrease the oxygenation of the blood, which results in hypoxia and subsequent tachycardia. Besides, decreased venous return causes a decrease in heart preload, which leads to decreased cardiac output, and the heart compensates by beating rapidly to maintain adequate perfusion to end organs.[16]

Thrombosis of the IVC can be caused by either compression or physical obstruction, which leads to venous stasis. Venous stasis is one of the three criteria of Virchow's triad of thrombus formation; the other two: hypercoagulable state and endothelial damage. The impedance in blood flow causes stasis, which promotes thrombus formation.[17]

The decreased venous return in inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) mimics the presentation of hypovolemic shock and causes tachycardia, diaphoresis, hypotension, shortness of breath on exertion, dizziness, and cold extremities. IVC congestion causes pallor, ascites, lower extremity peripheral edema, and hypoxia. IVCS also presents with generalized symptoms such as nausea, headache, malaise, and fatigue. In extreme cases, the decreased blood, either through thrombotic or non-thrombotic mechanisms, can lead to altered mental status and even death.[16]

History and Physical

Inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is not a primary diagnosis but is a consequence of any underlying pathology. As described in the pathophysiology section, the presentation of IVCS is dependent on the patient’s comorbidities and underlying diseases. Accurate diagnosis is based on a thorough history taking and physical examination.

The symptoms which a patient shows are in accordance with the pathophysiology of IVCS. It is important to inquire about other signs and symptoms, such as fatigue, dizziness, weight loss, abdominal pain, night sweats, anorexia, palpitations, diaphoresis, dizziness, shortness of breath on exertion. In addition, the history taking also has to get deep into previous illness history, including the history of abdominal surgeries, organ transplantation, lower extremity swelling and pain, family and past medical history of coagulopathy, prior deep venous thrombosis (DVT), as well as occupation and lifestyle.

A thorough physical examination will assist in the accurate diagnosis of IVCS. The vital signs will usually reveal hypotension, tachycardia, and possibly tachypnea with hypoxia. Signs of anemia, such as pallor or pale conjunctiva, might be the earlier sign of malignant disease, and with additional constitutional symptoms of malignancy can lead to the diagnosis of IVCS.

While there are no specific tests with pathognomonic findings of IVCS, certain findings such as lower extremity edema, signs of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE), cold and clammy extremities, abnormal neurological exam, hepatomegaly, and abdominal distention, lead to the decrease of venous return which then impair the perfusion of end organs.

Evaluation

Duplex ultrasound is the first line of modality can be used in a hemodynamically unstable patient. It is a rapid, accurate, and non-invasive modality to investigate the etiology of IVC obstruction. However, interference, i.e. obesity, limits the use of ultrasound in identifying the cause of obstruction. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy can also be used to reveal esophageal, gastric, or duodenal pathologies, especially tumor which compresses the IVC.[4]

CT abdomen and pelvis can then be used as an alternate non-invasive modality. Contrast venography, the standard for diagnosis, is used to assess the thrombotic obstructions of the abdomen in hemodynamically stable patients. Although it is an invasive procedure, it gives the most accurate finding of IVC obstruction and compression. Magnetic resonance (MR), a non-invasive but expensive instrument, can also be used to access obstruction of the IVC in hemodynamically stable patients and is replacing CT scans. Etiologies should be urgently obtained in hypotensive patients in order to prevent complications.[1]

Treatment / Management

The guideline treatment of inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) has not been clearly described. Therefore, treatment and management are determined by the etiology of the causative lesion and tailored to a patient’s condition. If the lesion is thrombotic, immediate treatment is focused on the prevention of propagation of the clot, causing a pulmonary embolism, and management of pain, edema, and the resulting hypotension. Either medical or surgical intervention can accomplish this. Medical treatments include anticoagulation using either low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), fondaparinux, or direct thrombin inhibitors. These medications reduce the buildup and propagation of the thrombosis but do not eliminate the primary thrombosis.

Endovascular procedures can subsequently be utilized to facilitate the introduction of thrombolytics to lyse the clot. These can include catheter-directed thrombolysis, pulse-spray pharmaco-mechanical thrombolysis, and then angioplasty with or without inserting stents, which increases patency of the IVC. Performing such procedures is required within a short period (within 14 days) of the onset of symptoms to minimize complications and decrease mortality rates. Surgical modalities such as thrombectomy, bypass, reconstruction/replacement, and ligation are used as a last resort due to the high invasive and significant intervention nature.[1]

If the stent placing is not advisable, placing IVC filters can alleviate symptoms for some time.[6] Recently, the use of IVC filters has increased, especially in advanced-stage cancer patients, in order to prevent the pulmonary embolus, although there is no explicit evidence of improved survival rate.[18] Temporary IVC filters are usually used in cancer patients during systemic chemotherapy.[19](B2)

If lesions are due to non-thrombotic etiologies such as malignancy, then the treatment is directed to manage the underlying cause of the compression. This may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or combination. Resection is a surgical option to remove tumor compression. However, resection is not possible to be done in unstable patients, thus, palliative care is provided. Another option is to place an intravascular stent or surgical bypass grafting, which increases the patency of the IVC to alleviate symptoms.[1][20] Recanalization of the occluded veins is usually done by implanting the metallic stents into the IVC from the superior vena cava via the right atrium.[21](B3)

IVCS patients of intrahepatic obstruction due to malignant hepatic enlargement are usually treated using strip radiotherapy to the intrahepatic IVC, with or without a hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy.[22] The IVC obstruction is generally managed by crossing the tumorous lesion with either a guidewire or Brockenbrough needle along with a Mullins sheath assembly, and then a balloon dilatation was done with the help of Inoue or Mansfield balloon.[23]

In some mild compression etiologies like pregnancy, physical maneuvers to move the uterus away from the IVC can be applied.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

Inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is characterized by tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnea, hypoxemia, and shortness of breath. The differential diagnosis of IVCS is broad, mainly because it is rarely ever diagnosed as a primary disease process. The differential diagnosis of IVCS are:

Prognosis

Prognosis of inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) depends on the underlying patient condition, including the hemodynamic status of the patient, the severity of compression or vein obstruction, the grading of the malignancy, and previous comorbidities. The outcome of patients who have inferior vena cava thrombosis overall relates to the embolic risk associated with DVT. If the IVC is occluded, pulmonary embolism does not present a significant risk. However, if the IVC lumen remains, embolization may occur.

Complications

Complications of inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) depend on the underlying comorbidity and patient's risk factors for the following but include:

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should be focused on modifiable risk factors and finding the etiology of the syndrome. Patients with an increased risk of thrombosis such as pregnancy, obesity, oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), smoking, venous insufficiency, immunocompromised, diabetes, or hypertension are at risk for developing obstruction of the IVC and an increased risk of malignant neoplasm development. Education needs to be tailored more towards mobility, weight loss, dietary modification, smoking cessation, stop alcohol consumption, and a healthier lifestyle.[15]

Pearls and Other Issues

Inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is not a primary diagnosis, but rather a diagnosis of exclusion. It mimics a variety of etiologies, and the signs and symptoms can overlap with other lethal conditions. So a prompt diagnosis can prevent significant morbidity and mortality. In addition to imaging, a thorough history and physical examination are vital to the diagnosis of IVCS. Although IVCS can predispose to thrombus formation, it protects against pulmonary embolism coming from the lower limbs deep vein thrombosis.[26]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Because of inferior vena cava syndrome (IVCS) is not a primary diagnosis; it is often missed and leads to adverse outcomes for the patients. Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is a better-recognized entity because of its specific presentation: right upper extremity swelling with skin discoloration and signs of decreased blood return to the right heart. In contrast, IVCS causes bilaterally lower extremity swelling, which can be misdiagnosed as congestive heart failure exacerbation, nephrotic syndrome, lymphangitis, or varicose veins.

IVCS can also be accompanied by symptoms consistent with hemodynamic instability, which can mimic several conditions such as circulatory shock, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary embolism, acute heart failure, acute pulmonary edema, etc. As a result, the responsibility of the entire interprofessional team, which includes both primary care providers, specialists such as trauma surgeons, transplant surgeons, hematologists, oncologists, and general surgeons, to name a few, nurses, social workers, pharmacists to counsel regarding medications that can cause prothrombotic states to advise the patients on how to reduce the risk of thrombosis, counsel on the importance of medications compliance if the patient is on anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy, and to promote lifestyle modifications to reduce the risk of thrombosis as well as obstruction of the IVC, which can cause severe morbidity and increased risk of mortality.

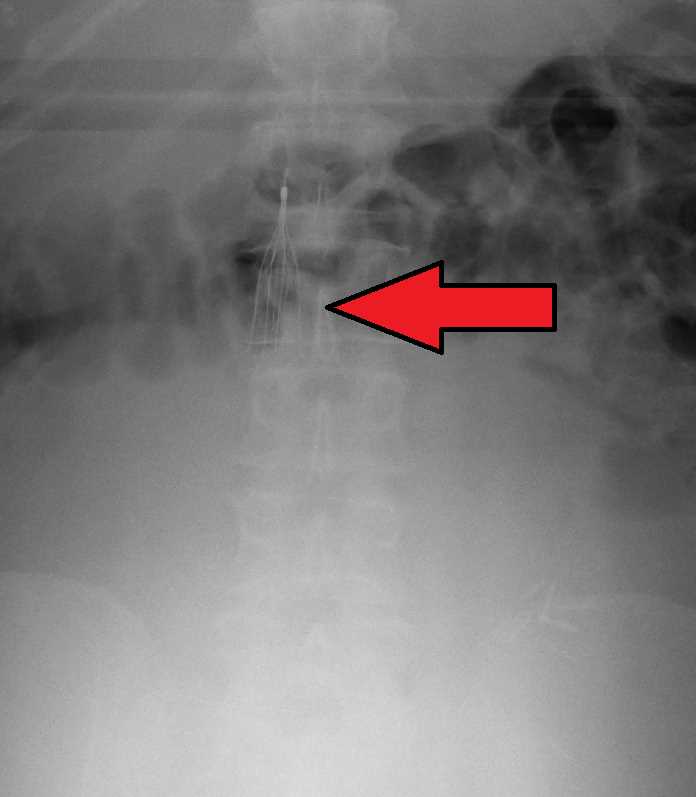

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

McAree BJ, O'Donnell ME, Fitzmaurice GJ, Reid JA, Spence RA, Lee B. Inferior vena cava thrombosis: a review of current practice. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2013 Feb:18(1):32-43. doi: 10.1177/1358863X12471967. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23439778]

Van Ha TG, Tullius TG Jr, Navuluri R, Millis JM, Leef JA. Percutaneous treatment of IVC obstruction due to post-resection hepatic torsion associated with IVC thrombosis. CVIR endovascular. 2019 Apr 25:2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s42155-019-0056-2. Epub 2019 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 32026991]

Beck AD. Renal cell carcinoma involving the inferior vena cava: radiologic evaluation and surgical management. The Journal of urology. 1977 Oct:118(4):533-7 [PubMed PMID: 916043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePatel SA. The inferior vena cava (IVC) syndrome as the initial manifestation of newly diagnosed gastric adenocarcinoma: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2015 Sep 28:9():204. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0696-3. Epub 2015 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 26411979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoto T, Yamasaki T, Kawashima R, Koide T, Yasuda T, Sendo H, Muramatsu S, Miyashita M, Ku Y. [A Case of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma with Inferior Vena Cava Invasion]. Gan to kagaku ryoho. Cancer & chemotherapy. 2020 Apr:47(4):634-636 [PubMed PMID: 32389967]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSauter A, Triller J, Schmidt F, Kickuth R. Treatment of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome and inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis in a patient with colorectal cancer: combination of SVC stenting and IVC filter placement to palliate symptoms and pave the way for port implantation. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2008 Jul:31 Suppl 2():S144-8 [PubMed PMID: 17605068]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKrywko DM, King KC. Aortocaval Compression Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613510]

Linicus Y, Kindermann I, Cremers B, Maack C, Schirmer S, Böhm M. Vena cava compression syndrome in patients with obesity presenting with edema and thrombosis. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2016 Aug:24(8):1648-52. doi: 10.1002/oby.21506. Epub 2016 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 27312050]

Liddell RP, Evans NS. May-Thurner syndrome. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2018 Oct:23(5):493-496. doi: 10.1177/1358863X18794276. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30187833]

DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G, American Association for the Study Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2009 May:49(5):1729-64. doi: 10.1002/hep.22772. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19399912]

Ishikura Y, Shimazu A, Odagiri S, Yoshimatsu H, Kadoya C, Okuma R. [A case of inferior vena cava thrombosis associated with cholelithiasis demonstrated by ultrasonic examination]. Nihon Geka Gakkai zasshi. 1986 Jul:87(7):813-7 [PubMed PMID: 3528816]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFontaine E, Garneau G, Lemieux S. Management of retroperitoneal hemorrhage compressing the inferior vena cava in a patient with a renal transplant: A case report. Radiology case reports. 2020 Mar:15(3):241-245. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.12.003. Epub 2020 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 31938078]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShrestha SM, Kage M, Lee BB. Hepatic vena cava syndrome: New concept of pathogenesis. Hepatology research : the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2017 Jun:47(7):603-615. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12869. Epub 2017 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 28169486]

Mulvihill SJ, Fonkalsrud EW. Complications of superior versus inferior vena cava occlusion in infants receiving central total parenteral nutrition. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1984 Dec:19(6):752-7 [PubMed PMID: 6440968]

Hollingsworth CM, Mead T. Inferior Vena Caval Thrombosis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725860]

Lier H, Bernhard M, Hossfeld B. [Hypovolemic and hemorrhagic shock]. Der Anaesthesist. 2018 Mar:67(3):225-244. doi: 10.1007/s00101-018-0411-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29404656]

Kushner A, West WP, Khan Suheb MZ, Pillarisetty LS. Virchow Triad. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969519]

Schunn C, Schunn GB, Hobbs G, Vona-Davis LC, Waheed U. Inferior vena cava filter placement in late-stage cancer. Vascular and endovascular surgery. 2006 Aug-Sep:40(4):287-94 [PubMed PMID: 16959722]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMasui S, Onishi T, Arima K, Sugimura Y. Successful management of inferior vena cava thrombus complicating advanced germ cell testicular tumor with temporary inferior vena cava filter. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2005 May:12(5):513-5 [PubMed PMID: 15948757]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGong ZH, Yan LJ, Sun JG. Postoperative radiotherapy to stabilize a tumor embolus in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A case report. Oncology letters. 2014 Oct:8(4):1856-1858 [PubMed PMID: 25202425]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSato Y, Inaba Y, Yamaura H, Takaki H, Arai Y. Malignant inferior vena cava syndrome and congestive hepatic failure treated by venous stent placement. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2012 Oct:23(10):1377-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.06.035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22999758]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHartley JW, Awrich AE, Wong J, Stevens K, Fletcher WS. Diagnosis and treatment of the inferior vena cava syndrome in advanced malignant disease. American journal of surgery. 1986 Jul:152(1):70-4 [PubMed PMID: 3728821]

Srinivas BC, Dattatreya PV, Srinivasa KH, Prabhavathi, Manjunath CN. Inferior vena cava obstruction: long-term results of endovascular management. Indian heart journal. 2012 Mar-Apr:64(2):162-9. doi: 10.1016/S0019-4832(12)60054-6. Epub 2012 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 22572493]

Sharma V, McGuire BB, Nadler RB. Implications of a 5-liter urinary bladder: inferior vena cava syndrome leading to bilateral pulmonary artery emboli. Urology. 2014 Jun:83(6):e11-2. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.02.025. Epub 2014 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 24746663]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMehta AJ, Kate AH, Gupta N, Chhajed PN. Interrupted inferior vena cava syndrome. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2012 Aug:60():48-50 [PubMed PMID: 23405525]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHagans I, Markelov A, Makadia M. Unique venocaval anomalies: case of duplicate superior vena cava and interrupted inferior vena cava. Journal of radiology case reports. 2014 Jan:8(1):20-6. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v8i1.1354. Epub 2014 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 24967010]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence