Introduction

Adrenal metastases are the most common malignant lesions involving the adrenal gland and the second most common tumor of the adrenal gland after benign adenomas. These metastases were primarily found on autopsy. However, with the increasing role of CT, MRI, and PET in diagnosing, staging, and follow-up malignancies, adrenal metastases are increasingly found incidentally.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

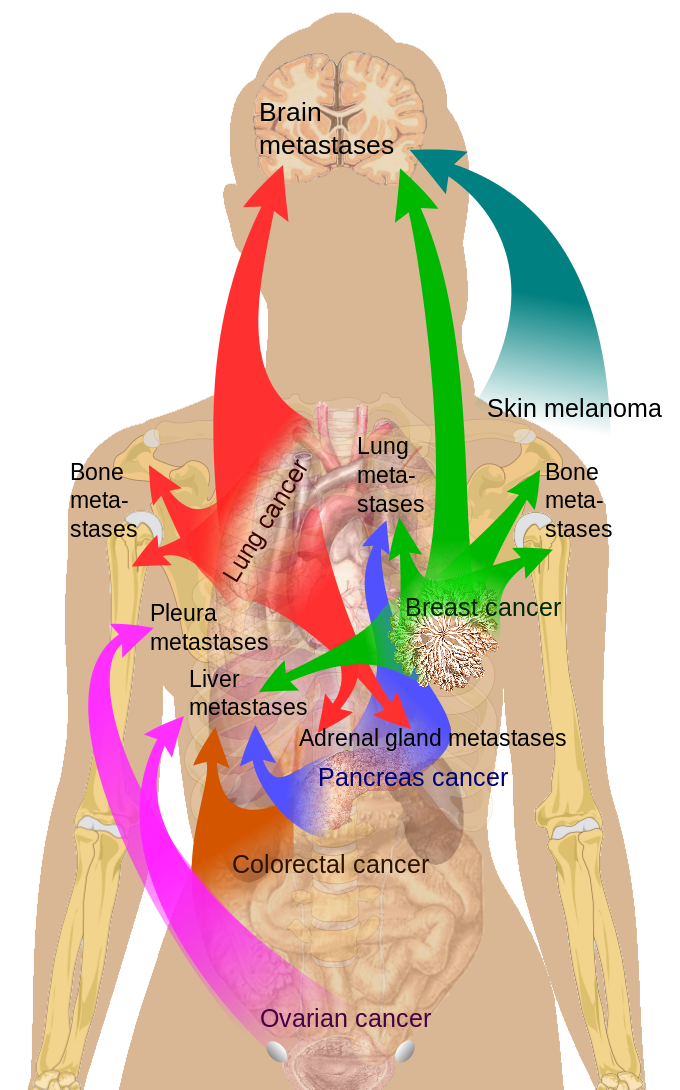

Adrenal glands are the fourth most common site of metastases in malignant disease, which is significant considering the relatively small size of adrenals. Adrenal metastasis can occur from primaries in the lung (39%), breast (35%), melanoma, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and kidney, among other places (see Image. Breast Cancer Metastasis Sites).[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

About 30% to 70% of incidentally discovered adrenal masses in patients with a history of cancer or a recently diagnosed extra-adrenal malignancy are metastases. The incidence of these metastases might be higher in autopsies. For example, in a study, the incidence of adrenal metastases from renal cell carcinoma was 6% to 29% in autopsy series, but from clinical diagnosis, it was less frequent, at 2% to 10%. The median time from cancer diagnosis to the identification of adrenal metastases is about 2.5 years, although adrenal metastases have been reported up to 22 years after initial treatment of primary tumors. It is uncommon for isolated adrenal metastases to occur before identification of the primary malignancy. The increasing incidence of breast and lung cancer, as well as other types of cancer, has also increased in adrenal metastases.

Pathophysiology

Metastatic spread to the adrenals is mainly hematogenous and can be bilateral. Lymphogenous spread to the adrenals is widely debated. It is poorly understood why metastases have a predilection to adrenals, although it is hypothesized that it is due to its rich sinusoidal blood supply. On gross pathology, metastases are gray-white, tan-brown, or black-colored, solitary or multiple, firm heterogeneous masses, with occasional hemorrhage and necrosis. On cytology, metastatic lesions are morphologically similar to the primary tumor. The tumor cells exhibit increased nuclear hyperchromasia, prominent nucleoli, frequent mitotic figures, necrotic debris, and intact cells with increased nuclear and cytoplasmic ratios against adrenal adenomas composed of relatively uniform cells without mitosis or necrosis. Immunohistochemical markers could be helpful to separate metastatic tumors from primary, adrenocortical tumors.[7][8][9]

History and Physical

Most patients with adrenal metastases are asymptomatic. Patients may have localized symptoms like back or abdominal pain due to the tumor mass effect if the tumor is large or rapidly growing. This could indicate local invasion or retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Adrenal metastases do not usually result in adrenal insufficiency unless a significant portion of the bilateral adrenals ( more than 90%) are affected. These patients can present with anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, lethargy, fever, confusion, and electrolyte imbalances secondary to adrenal insufficiency. They can be easily confused with the manifestations of the neoplastic disease. Adrenal crises due to episodes of symptomatic hemorrhage into adrenal glands, which were infiltrated by a metastatic tumor, have rarely been noted.

Evaluation

The presence of metastases influences the management of the primary malignancy, and further evaluation is often needed, especially in patients with cancer with no other sites of metastases besides the adrenal glands.

Imaging

Most adrenal tumors are benign, and many are indeterminate on imaging. Based on current studies, no single imaging modality can be considered the gold standard for the comprehensive evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas or to distinguish malignant from benign adrenal masses. CT and MRI assess lipid content to differentiate benign (high lipid content) from potentially malignant (low lipid content) adrenal masses. They are mainly used to identify benign lesions and exclude adrenal malignancy. FDG-PET/CT is mainly used to detect malignant diseases. The pre-test probability of an indeterminate adrenal mass being malignant is greater in a patient with a history of extra-adrenal malignancy but requires careful exclusion of other causes. Any available previous imaging is extremely useful for comparing and determining the onset and growth timeline.

On CT, adrenal metastases typically have a higher unenhanced density (greater than 10 HU), are heterogeneous, and have a delay in contrast medium washout compared to adenomas (pre-contrast HU less than 10, homogeneous, and rapid contrast washout). Assessment of precontrast density by itself is not as specific because a third of the benign adrenal adenomas are lipid-poor and have HU greater than 10, thereby necessitating CT with contrast enhancement for washout characteristics if the adrenal mass has attenuation higher than 10 HU on non-contrast CT. Although precontrast HU less than 10 is unlikely to be malignant, we must be cautious about a pooled false negative rate of 7% in patients with a history of extra-adrenal malignancy. Measurement of HU needs to be standardized to be accurate. The region of interest during the attenuation measurement should encompass two-thirds of the largest axial diameter of the mass and avoid boundaries. It is inaccurate if areas of necrosis are present. Lesions greater than 4 centimeters have a higher risk of malignancy. The growth of an adrenal lesion over short-term imaging follow-up (ie, 6 months), local invasion, irregular borders, and central necrosis are predictors of primary adrenal malignancy and adrenal metastasis. Calcification is rare in adrenal metastases.

MRI has a limited role in characterizing lipid-poor adrenal masses, especially when pre-contrast HU>20-30 and thus adrenal metastases. On MRI, adrenal metastases are isointense or slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images with heterogeneous enhancement after contrast administration. On chemical-shift MRI, metastases typically do not show signal drop during out-of-phase sequences due to the poor lipid nature of the adrenal metastasis. Rarely, metastases secondary to clear renal cell carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma can mimic adenoma on chemical shift MRI due to intracytoplasmic lipids.

An 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET (18F-FDG PET), although not a specific marker for cancer cells, has 74% to 100% sensitivity and 66% to 100% specificity in differentiating adrenal masses as benign or malignant in patients with known primary cancers. The degree of hypermetabolism on a PET is measured by standardized uptake value. The mean adrenal standardized uptake value max and adrenal-to-liver standardized uptake value ratio are higher for adrenal metastases than for adenomas. An adrenal max standardized uptake value cutoff of 3.1 has been shown to have a sensitivity of 98.5% and specificity of 92% for differentiating benign adenomas from malignant lesions. An SUV adrenal lesion/liver ratio greater than 1.8 with a history of extra-adrenal malignancy has a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 96% to detect malignant disease. PET-CT is subject to both false positive (some benign adrenal adenomas, inflammatory lesions such as sarcoidosis and tuberculosis) and false negative results (less than 1 cm metastatic nodules, metastases with hemorrhage or necrosis, metastases from non-FDG avid malignancies) and cannot differentiate adrenal metastases from adrenocortical carcinoma.

Biopsy

CT-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) may be useful when imaging is equivocal (has not been conclusively characterized as benign), the lesion is hormonally inactive, and most importantly, the management of the patient would be altered with information from histology. Therefore, FNA is not useful in the setting of widespread metastatic disease but may have utility in evaluating the oligometastatic disease of the adrenal gland. It is of utmost importance that pheochromocytoma is excluded with biochemical testing (plasma or urinary metanephrines) before the biopsy to avoid the potential risk of hypertensive crisis and life-threatening complications. FNA should not be done if the mass is likely to be adrenocortical carcinoma because this rarely provides an answer and also because of the risk of dissemination precluding R0 resection. Although FNA cannot differentiate between benign adenoma and adrenocortical carcinoma, FNA is very useful in confirming the presence of metastatic disease in adrenal lesions with a sensitivity of 80% to 90% and a positive predictive value of 100%. FNA can potentially have non-diagnostic results (0% to 28%) and complications (2.5% to 13%). Most complications are self-limiting but can include adrenal hemorrhage, pain, pancreatitis, pneumothorax, and hematuria.

Biochemical Evaluation

With CT, MRI, and PET scans, it is impossible to distinguish pheochromocytoma from metastases reliably. Therefore, it is important to rule out pheochromocytoma in patients with extra-adrenal malignancy with an indeterminate mass, even if the adrenal mass is likely to be metastatic. Additional hormonal workups for hyperfunctioning (Cushing syndrome, primary hyperaldosteronism) should be individualized, and patients with advanced stage and limited life expectancy are unlikely to benefit. As bilateral adrenal metastases can lead to adrenal insufficiency in rare cases, all patients with potentially bilateral metastases should be clinically evaluated for adrenal insufficiency. The initial test is morning adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, and serum electrolytes. If the diagnosis is not cleared by the patient's history and initial testing, an ACTH stimulation test should be done. In unilateral adrenal metastases, adrenal insufficiency is unlikely and typically does not need evaluation. In patients with a history of cancer and the use of glucocorticoids as part of a chemotherapy regimen or otherwise over the last year, the possibility of glucocorticoid-related adrenal suppression should be considered. In this scenario, stress dose glucocorticoids during admission for critical illness, surgery, or procedures requiring conscious sedation or anesthesia should be strongly considered to prevent adrenal crisis.

Treatment / Management

The most effective treatment of adrenal metastases is first to treat the primary cancer, usually with chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Surgical resection is considered in patients with isolated adrenal metastasic disease or with other resectable or potentially curable metastases. A PET scan is useful for detecting oligometastatic disease in the adrenals and excludes extra-adrenal metastatic disease if not already evident by CT or MRI. An absence of local invasion into contiguous structures and a disease-free interval greater than 6 months from the original cancer diagnosis are considered good prognostic factors with adrenalectomy. Results vary depending on the cancer site of origin. There is no evidence supporting an adrenalectomy for tumors with an unknown primary source. Minimally invasive laparoscopic adrenalectomy is as effective as open adrenalectomy for adrenal metastasectomy with proven reduction in postoperative pain, morbidity, and length of stay. Adrenal masses less than 6 cm without local invasion are amenable to laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, arterial ablation, chemoablation, cryoablation, and CT-guided or MR thermotherapy-controlled laser-induced, interstitial thermotherapy have been used with curative and palliative intent and have shown variable results. Imaging-guided thermal ablation of adrenal metastases with radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, and microwave ablation has the potential for local tumor control. Still, risks include hemodynamic complications (hypertensive urgency) and adrenal insufficiency. The pre-ablation alpha blockade has been shown to reduce the severity of hypertensive episodes but increases the need for vasopressors periprocedural. Assessing adrenal function after ablation and providing glucocorticoid replacement as needed is important.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for adrenal metastasis include the following:

- Adrenal amyloidosis

- Adrenal incidentaloma

- Adrenal hamartoma

- Adrenal myelolipoma

- Adrenal teratoma

- Neuroblastoma imaging

- Pancreatic cancer

- Plexiform neurofibromas

- Renal cell carcinoma

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Adrenal metastases are the most common malignant lesions involving the adrenal gland and the second most common tumor of the adrenal gland after benign adenomas. These metastases were primarily found on autopsy. However, with the increasing role of CT, MRI, and PET in diagnosing, staging, and follow-up malignancies, adrenal metastases are increasingly found incidentally. The management of adrenal metastatic lesions is best done with an interprofessional team that includes an oncologist, a surgeon, a radiologist, a primary care provider, an internist, and a pathologist. The key is to find out the primary. In most cases, the biggest difficulty is determining whether the adrenal lesion is benign or metastatic. Sometimes, a biopsy or laparoscopy may be required. If the lesion is metastatic, the prognosis for most patients is poor.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Breast Cancer Metastasis Sites

Medical Gallery of Mikael Häggström, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Lin B, Yang H, Yang H, Shen S. A Rare Case of Bilateral Malignant Paragangliomas. World neurosurgery. 2019 Apr:124():12-16. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.131. Epub 2019 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30611952]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePandey T, Pandey S, Singh V, Sharma A. Bilateral renal cell carcinoma with bilateral adrenal metastasis: a therapeutic challenge. BMJ case reports. 2018 Dec 13:11(1):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-227176. Epub 2018 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 30567248]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHikami K, Ueda M, Shibasaki N, Yasui H, Akao T. [A Case of Renal Cell Carcinoma withIpsilateral Renal Pelvic Metastasis Mimicking Double Cancer]. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2018 Nov:64(11):439-443. doi: 10.14989/ActaUrolJap_64_11_439. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30543743]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlmeida MQ,Bezerra-Neto JE,Mendonça BB,Latronico AC,Fragoso MCBV, Primary malignant tumors of the adrenal glands. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2018 Dec 10; [PubMed PMID: 30540124]

Klikovits T, Lohinai Z, Fábián K, Gyulai M, Szilasi M, Varga J, Baranya E, Pipek O, Csabai I, Szállási Z, Tímár J, Hoda MA, Laszlo V, Hegedűs B, Renyi-Vamos F, Klepetko W, Ostoros G, Döme B, Moldvay J. New insights into the impact of primary lung adenocarcinoma location on metastatic sites and sequence: A multicenter cohort study. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2018 Dec:126():139-148. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.11.004. Epub 2018 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 30527178]

Blažeković I, Jukić T, Granić R, Punda M, Franceschi M. An Unusual Case of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Iodine-131 Avid Metastasis to the Adrenal Gland. Acta clinica Croatica. 2018 Jun:57(2):372-376. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.02.20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30431733]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElsayes KM, Emad-Eldin S, Morani AC, Jensen CT. Practical Approach to Adrenal Imaging. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2018 Aug:45(3):365-387. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2018.03.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30031460]

Hatano K,Horii S,Nakai Y,Nakayama M,Kakimoto KI,Nishimura K, The outcomes of adrenalectomy for solitary adrenal metastasis: A 17-year single-center experience. Asia-Pacific journal of clinical oncology. 2018 Sep 30; [PubMed PMID: 30270570]

Burjakow K, Fietkau R, Putz F, Achterberg N, Lettmaier S, Knippen S. Fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy for adrenal metastases: contributing to local tumor control with low toxicity. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie : Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft ... [et al]. 2019 Mar:195(3):236-245. doi: 10.1007/s00066-018-1390-3. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30374590]