Introduction

Renal artery stenosis is narrowing of the one or both of renal arteries. It is the major cause of hypertension and according to some reports is the cause of hypertension in 1% to 10% of the 50 million people in the United States.[1] Atherosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia most often cause it. [2]Other associated complications of renal artery stenosis are chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are two major causes of unilateral renal artery stenosis (RAS):

- Atherosclerosis (60% to 90%): Atherosclerosis primarily affects patients (men over the age of 45 years) and usually involves the aortic orifice or the proximal 2 cm of the main renal artery. This disorder is particularly common in patients who have atherosclerosis, however, can also occur as a relatively isolated renal lesion. Any of the multiple renal arteries (occurring in 14% to 28%) may be affected. Risk factors for atherosclerosis include dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, viral infection, immune injury, and increased homocysteine levels.

- Fibromuscular dysplasia (10% to 30%): In contrast to atherosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia most often affects women younger than the age of 50 years and typically involves the middle and distal main renal artery or the intrarenal branches.

- Other less common causes (less than 10%) include thromboembolic disease, arterial dissection, infrarenal aortic aneurysm, vasculitis (Takayasu arteritis, Buerger disease, polyarteritis nodosa, post radiation), neurofibromatosis type 1, retroperitoneal fibrosis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of renal artery stenosis is probably less than 1% of patients with mild hypertension but can increase to as high as 10 % to 40% in patients with acute (even if superimposed on a preexisting elevation in blood pressure), severe, or refractory hypertension. Several studies report the prevalence of unilateral stenosis (compared with bilateral stenosis) approximately from 53 % to 80%.

Studies suggest that ischemic nephropathy may be the cause of 5% to 22% of advanced renal disease in all patients older than 50 years. Patients with fibromuscular dysplasia have involvement of the renal arteries in proximately 75% to 80% of cases. Roughly two-thirds of patients have involvement of multiple renal arteries. Fibromuscular dysplasia is more common in females than in males.[4]

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis of Hypertension

In atherosclerosis, the initiator of endothelial injury although not well understood can be, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, viral infection, immune injury, or increased homocysteine levels. [5]At the lesion site, permeability to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and macrophage migration increases with subsequent proliferation of endothelial and smooth muscle cells and ultimate formation of atherosclerotic plaque. Renal blood flow, which is significantly greater than the perfusion to other organs, along with glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure is an important determinant of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). In patients with renal artery stenosis, the chronic ischemia produced by the obstruction of renal blood flow leads to adaptive changes in the kidney which include the formation of collateral blood vessels and secretion of renin by juxtaglomerular apparatus. The renin enzyme has an important role in maintaining homeostasis in that it converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin I. Angiotensin I has then converted to angiotensin II with the help of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in the lungs. Angiotensin II is responsible for vasoconstriction and release of aldosterone which causes sodium and water retention, thus resulting in secondary hypertension or renovascular hypertension.[1][6][1]

Pathogenesis of Chronic Renal Insufficiency

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is autoregulated by angiotensin II and other modulators between the afferent and efferent arteries. The maintenance of GFR fails when renal perfusion pressure falls below 70 mmHg to -85 mmHg. Therefore significant functional impairment of autoregulation, leading to a decrease in the GFR, is only likely to be observed until arterial luminal narrowing exceeds 50%. Studies demonstrate that a moderate reduction in renal perfusion pressure (up to 40%) and renal blood flow (mean 30%) cause reduction in glomerular filtration, however, tissue oxygenation within the kidney cortex and medulla can adapt without the development of severe hypoxia. As an inference patients at an early stage can be treated with medical therapy without progressive loss of function or irreversible fibrosis in many cases, sometimes for many years.

It is reported that more advanced stenosis corresponding to a 70% to 80% of vascular occlusion leads to demonstrable cortical hypoxia, and it is proposed that this hypoxia produce rarefaction of microvessels, as well as activation of inflammatory and oxidative pathways that cause interstitial fibrosis. [7]Therefore loss of renal function in renovascular disease in addition to being a usually reversible consequence of antihypertensive therapy can reflect a progressive narrowing of the renal arteries and/or progressive intrinsic renal disease. Eventually, long-standing parenchymal injury becomes an irreversible process. At this point, restoring renal blood flow provides no recovery of renal function or clinical benefit.

History and Physical

Clinical manifestations that suggest the likelihood of renovascular disease as a cause of hypertension include:

- Severe hypertension that may be treatment resistant, refractory to therapy with three or more drugs. A few patients with ischemic nephropathy may be normotensive, which may be due in part to a reduced cardiac output[8]

- Young-onset hypertension with a negative family history

- Abrupt onset before age 50, likely fibromuscular dysplasia as the underlying cause while abrupt onset after age 50, more likely atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis as the cause[9]

- An acute and sustained rise in serum creatinine of more than 30% following the administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Significant variability of serum creatinine concentration that may be due to changes in volume status

- Recurrent episodes of flash pulmonary edema and/or refractory heart failure

- Renal asymmetry, unilateral small kidney

- Unexplained hypokalemia

- Deterioration of renal function after placement of an endovascular aortic stent graft

- Patients with ischemic nephropathy may also manifest a persistent and progressive reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

- Unexplained rise in BUN

- Lack of evidence supporting an alternative cause of renal disease, for instance, an abnormal urinalysis, proteinuria, a paraprotein, or use of a nephrotoxic drug.

Other findings include abdominal bruit and flank bruit. Patients with renovascular disease frequently have severe retinopathy, peripheral or coronary vascular disease. [10][1]RAS can complicate pre-existing hypertension. In this presentation, the concern is for patients for whom RAS is complicating the management of their hypertension.

Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

Conducted in renovascular disease patient comprise following:

- Serum creatinine levels to assess the degree of renal dysfunction

- A 24-hour urine collection, or a protein-creatinine ratio on a random void urine specimen, to more accurately assess the level of renal dysfunction and for measuring the degree of proteinuria. The renal vascular disease is more often associated with minimal-to-moderate degrees of proteinuria, which are usually not in the nephrotic range

- Urinalysis for seeing red blood cells or red blood cell casts (a hallmark feature of glomerulonephritis) is absent

- Serologic tests for systemic lupus erythematosus or vasculitis if these conditions are suggested (e.g., antinuclear antibodies, C3, C4, antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies).

Imaging Studies

Testing for the renovascular disease is warranted who fulfill following criteria:

- The clinical findings suggest a cause of secondary hypertension rather than primary hypertension. There are a variety of clinical and laboratory findings that suggest renovascular disease as a cause of secondary hypertension as mentioned earlier

- Other causes of secondary hypertension such as primary kidney disease, primary aldosteronism, or pheochromocytoma have been excluded before investigating for renal artery stenosis

- A corrective intervention is planned if a clinically significant stenotic lesion is found.

The gold standard for diagnosing renal artery stenosis is renal arteriography. However, a variety of less invasive tests are being employed for evaluation for testing purposes. The choice of test should be based upon institutional expertise and patient factors. If the noninvasive test is inconclusive and the clinical suspicion remains high, conventional renal arteriography is recommended.

- Duplex Doppler ultrasonography

- Computed tomographic angiography (CTA)

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)[11]

Duplex Doppler Ultrasonography

Duplex ultrasonographic scanning is a noninvasive, relatively inexpensive technique that can be used in patients with any level of renal function. However, it is operator dependent and has variable sensitivity. Two approaches are used to detect RAS with Doppler Ultrasound.

- Direct Visualization of the Renal Arteries: The first approach involves direct scanning of the main renal arteries with color or power Doppler US followed by spectral analysis of renal artery flow using an anterior or anterolateral approach. Owing to various factors essentially as gas interposition and the anatomy of the left renal artery, a complete examination of both renal arteries can be achieved in only 50%–90% of cases. Signal enhancement can be achieved by administering contrast agents that facilitate visualization of the renal arteries. Four criteria are currently used to diagnose significant proximal stenosis:

- An increase in peak systolic velocity in the renal artery (the post-stenotic threshold for significant RAS is 100 cm/sec to 200 cm/sec is reported)

- A renal-to-aortic peak systolic velocity ratio of greater than 3.5

- Turbulent post-stenotic site

- Visualization of the renal artery without any detectable Doppler signal, an observation that signals occlusion.

- Analysis of Intra-renal Doppler Waveforms: The different segments of kidneys are scanned via trans lumbar approach systematically to detect a stenosis of a segmental or accessory renal artery. Quantitative criteria proposed for detection of significant RAS:

- Acceleration of less than 370 cm/sec to 470 cm/sec. The early systolic acceleration seems to be the best predictor of renal artery narrowing

- Acceleration time greater than 0.05 sec to 0.08 sec

- Change in the resistive index (RI) of greater than 5% between the right and left kidneys. This value should be measured along the initial portion of the systolic rise and avoid including the late compliance peak

- A dampened presentation (pulsus tardus) of an intrarenal Doppler waveform indicates stenosis

- The presence of an early systolic peak can be interpreted as a sign of normality; however, the absence of an early systolic peak is not necessarily indicative of stenosis.[12]

ACE Inhibitor Scintigraphy

A kidney with renovascular hypertension particularly RAS exhibits impaired function during Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibition. This phenomenon is believed to be a manifestation of disruption of the autoregulation system of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which becomes dependent on angiotensin II under circumstances of low perfusion. Although a decline in the GFR can be induced by ACE inhibition in the affected kidney of patients with unilateral RAS, the contralateral kidney preserves the overall renal function. This change in renal function in unilateral RAS-induced by ACE inhibition can be revealed with scintigraphy. In these patients, ACE inhibitor scintigraphy induces significant changes in the time-activity curves of the affected kidney in contrast to the baseline curves. ACE inhibitor scintigraphy is performed 1 hour after an oral dose of 25 mg of captopril or 15 minutes after an intravenous dose of 0.04 mg/kg of enalapril maleate. Any pre-existing ACE inhibitor therapy should be ceased 2 to 5 days before the study according to the half-life of the drug, and adequate hydration must be ensured. Blood pressure should be monitored during the procedure. Baseline and ACE inhibitor scintigraphy is performed after intravenous injection of technetium-99m mercaptoacetyltriglycine (MAG), iodine-131 ortho iodohippurate (OIH), or Tc-99m diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA). Sequential images and scintigraphic curves are acquired for 30 minutes after injection of the radiotracer. Time-activity curves are generated from the renal cortex and pelvis. Renal uptake is measured every 1-min to 2-min intervals after injection.

Tc-99m MAG and I-131 OIH are excreted through tubular secretion while Tc-99m DTPA is excreted through glomerular filtration. In patients with RAS, ACE inhibitors prompt renal retention of the radiotracer due to decreased urinary output secondary to reduced GFR.

The general interpretive criteria are mentioned under:

- A normal ACE inhibitor scintigram is indicative of low probability (less than 10%) of renovascular hypertension

- A small, poorly functioning kidney (less than 30% uptake with a time of maximum activity [T] 2 minutes or less) that shows no change on the ACE inhibitor scintigram and bilateral symmetric abnormalities such as cortical retention of tubular agents signal an intermediate probability of RVH

- Criteria associated with a high probability of renal artery stenosis include worsening of the scintigraphic curve, decrease in the relative uptake, prolongation of the renal and parenchymal transit time, increase in the 20-minute/peak uptake ratio of 0.15 or greater, and prolongation of T.

Specific interpretive criteria for Tc-99m MAG and I-131 OIH scintigrams are following:

Unilateral parenchymal retention after ACE inhibition (demonstrated as a change in the 20-minute/peak uptake ratio of 0.15 or greater, a significantly prolonged transit time, delay in excretion of the tracer into the renal pelvis) is the most important criterion for Tc-99m MAG and I-131 OIH scintigraphy and represents a high probability (greater than 90%) of renovascular hypertension.

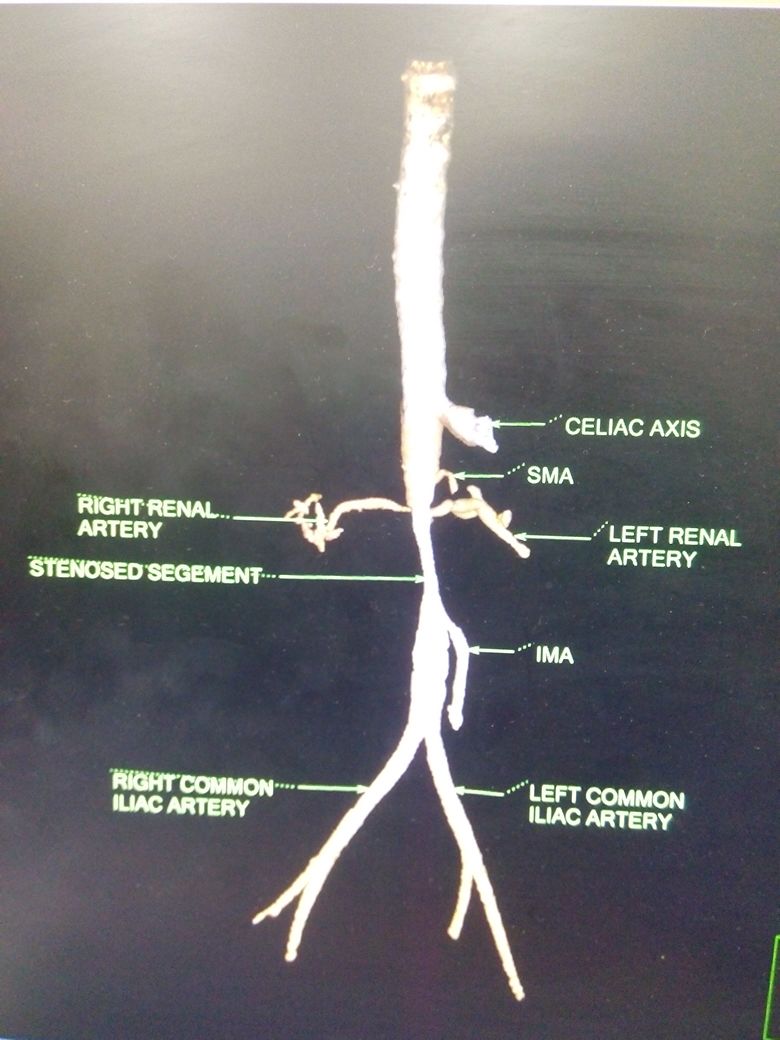

CT Angiography

Raw data and three-dimensional reconstruction of the renal vascular tree are a sensitive and specific method of visualizing the whole vasculature including the presence of accessory renal arteries. Images are acquired with thin collimation and bolus tracking at the abdominal aorta. It is a useful technique as it avoids arterial catheterization and puncture and thus the risk of atheroembolism, but it has associated risk of contrast associated nephropathy, particularly in patients with pre-existing chronic kidney disease.

MR Angiography

Different imaging methods can be used:

- Time of flight (TOF) in which the high velocity of the blood jet at the level of stenosis appears as signal void or simply black

- Phase contrast technique

- Gadolinium-enhanced MR angiography: capable of performing breath-hold three-dimensional spoiled gradient-echo imaging with short repetition times and echo times. The angiographic contrast is the result of the T1-shortening effect of the intravenously administered paramagnetic contrast agent. Blood is rendered bright, whereas stationary tissues remain dark. Subtraction of nonenhanced images removes all background signals and improves the vessel-to-background signal. Usually, a double dose of gadolinium contrast material (0.2 mmol/kg) is injected at a rate of 1.5 mL/sec to –2 mL/sec.

According to several case studies, MRA has been justified only for diagnosing stenosis situated in the proximal 3 cm to 3.5 cm of renal arteries with the limitation to reveal distal renal artery stenosis, segmental renal artery stenosis and the presence of the metallic stent. [11]In some cases, renal impairment does not permit the use of contrast, in which case TOF imaging is beneficial.

Conventional Arteriography

As mentioned initially conventional angiography remains the standard for the confirmation and identification of renal artery occlusion. There are several methods to perform renal arteriography including conventional aortography, intravenous subtraction angiography, intra-arterial subtraction angiography, or carbon dioxide angiography. Conventional aortography produces excellent radiographic images of the renal artery, but it requires an arterial puncture, carries the risk of thromboembolism, and uses a moderate amount of contrast with the risk of contrast-induced acute tubular necrosis. Low-osmolar contrast material can reduce this risk. Intravenous subtraction angiography is sensitive for identifying stenosis of the main renal artery and avoids the use of a high volume of contrast, the risk of arterial puncture and arterial atherosclerotic emboli, but does not demonstrate accessory or branch renal arteries sufficiently. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiographic technique had a high diagnostic accuracy compared to conventional angiography and associated fewer complications due to the lower dose of contrast, and smaller catheter size used. Carbon dioxide angiography is an alternative angiographic contrast agent to avoid the risk of conventional nephrotoxic contrast agents in patients with the severe renal disease.

Treatment / Management

Initial treatment for renal artery stenosis is observation instead of revascularization when either stenosis is 50% to 80%, and scintigraphy findings are negative, or the degree of stenosis is less than 50%. The management which involves serial control every 6 months with duplex scanning, accurate correction of dyslipidemia, use of drugs that block platelet aggregation, may require three or more different drugs to control hypertension.[13] Preferably angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are used for the purpose. Unfortunately, these two classes of drugs can also lead to increased serum creatinine levels and hyperkalemia, limiting their utility. In such a case, calcium channel blockers are a potential replacement. Strict control of serum cholesterol, with the use of statins in the regimen.[9]

The degree of renal artery stenosis that would justify any intervention attempt is greater than 80% in patients with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney regardless of whether they have renal insufficiency or not.

When renal function is normal or nearly normal, revascularization is recommended for prevention of renal insufficiency if the patient fulfills the mentioned criteria:

- The degree of renal artery stenosis is greater than 80% to 85%

- The degree of RAS is 50% to 80%, and captopril-enhanced scintigraphy demonstrates the presence of intrarenal renal artery stenosis.

When renal function abnormality is present, the criteria for revascularization are as follows:

- The serum creatinine level is less than 4 mg/dL

- The serum creatinine level is greater than 4 mg/dL but with a possible recent renal artery thrombosis

- The degree of stenosis is higher than 80%

- The serum creatinine level increases after administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- The degree of stenosis is 50% to 80%, and the scintigraphy results are positive for RAS.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute kidney injury

- Azotemia

- Chronic Glomerulonephritis

- Hypersensitivity Nephropathy

- Hypertension

- Malignant Hypertension

- Nephrosclerosis

- Renovascular hypertension

- Uremia

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The team must be aware of expected exam findings and abnormalities in testing. Clinicians and nurses should work together to educate the patient and family and provide coordinated care. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ma N, Wang SY, Sun YJ, Ren JH, Guo FJ. [Diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for accessory renal artery among patients suspected of renal artery stenosis]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2019 Mar 19:99(11):838-840. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.11.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30893727]

van Twist DJ, Houben AJ, de Haan MW, de Leeuw PW, Kroon AA. Pathophysiological differences between multifocal fibromuscular dysplasia and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Journal of hypertension. 2017 Apr:35(4):845-852. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001243. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28060190]

Eusébio CP, Correia S, Silva F, Almeida M, Pedroso S, Martins S, Diais L, Queirós J, Pessegueiro H, Vizcaíno R, Henriques AC. Refractory ascites and graft dysfunction in early renal transplantation. Jornal brasileiro de nefrologia. 2019 Oct-Dec:41(4):570-574. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2018-0175. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30897191]

Al-Katib S, Shetty M, Jafri SM, Jafri SZ. Radiologic Assessment of Native Renal Vasculature: A Multimodality Review. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2017 Jan-Feb:37(1):136-156. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28076021]

Park KH, Park WJ. Endothelial Dysfunction: Clinical Implications in Cardiovascular Disease and Therapeutic Approaches. Journal of Korean medical science. 2015 Sep:30(9):1213-25. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.9.1213. Epub 2015 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 26339159]

Tetteh PW, Antwi-Boasiako C, Gyan B, Antwi D, Adzaku F, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Obed S. Impaired renal function and increased urinary isoprostane excretion in Ghanaian women with pre-eclampsia. Research and reports in tropical medicine. 2013:4():7-13. doi: 10.2147/RRTM.S40450. Epub 2013 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 30890871]

Gloviczki ML, Glockner JF, Crane JA, McKusick MA, Misra S, Grande JP, Lerman LO, Textor SC. Blood oxygen level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging identifies cortical hypoxia in severe renovascular disease. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2011 Dec:58(6):1066-72. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171405. Epub 2011 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 22042812]

Textor SC. Renal Arterial Disease and Hypertension. The Medical clinics of North America. 2017 Jan:101(1):65-79. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.08.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27884236]

Ricco JB, Belmonte R, Illuminati G, Barral X, Schneider F, Chavent B. How to manage hypertension with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis? The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2017 Apr:58(2):329-338. doi: 10.23736/S0021-9509.16.09827-X. Epub 2016 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 27998047]

Aboyans V, Desormais I, Magne J, Morange G, Mohty D, Lacroix P. Renal Artery Stenosis in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Long-term Prognosis. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2017 Mar:53(3):380-385. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.10.029. Epub 2016 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 27919610]

Liang KW, Chen JW, Huang HH, Su CH, Tyan YS, Tsao TF. The Performance of Noncontrast Magnetic Resonance Angiography in Detecting Renal Artery Stenosis as Compared With Contrast Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Angiography Using Conventional Angiography as a Reference. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2017 Jul/Aug:41(4):619-627. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000574. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28099225]

Boddi M. Renal Ultrasound (and Doppler Sonography) in Hypertension: An Update. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:956():191-208. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_170. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27966109]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFournier T, Sens F, Rouvière O, Millon A, Juillard L. [Management of atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis in 2016]. Nephrologie & therapeutique. 2017 Feb:13(1):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2016.07.450. Epub 2016 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 27887845]