Introduction

Steatocystoma is a benign cystic condition arising from the pilosebaceous unit. Unlike the misnomer associated with epidermal inclusion cysts, steatocystomas are true sebaceous cysts with sebaceous glands located within the wall of the cyst lining. Steatocystomas can occur as single (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple (steatocystoma multiplex) lesions and typically present as smooth, round nodules located on the chest, axillae, or groin. These cysts are relatively small, ranging from a few millimeters to about a centimeter in diameter, and are located within the skin. If these cysts are punctured, they release an oily, fluid-like substance.[1] Lesions are typically local in these common areas, although more unusual facial, acral, and congenital linear forms have been described.[2] Although most cases are sporadic, familial forms or links to other congenital abnormalities should prompt a detailed family history and possible genetic testing. Diagnosis relies on clinical evaluation, dermoscopy, and histopathological confirmation.

Steatocystomas are typically asymptomatic and cause few complications beyond aesthetic concerns; therefore, treatment is typically unnecessary unless it is for cosmetic purposes or to achieve diagnostic clarity. However, these lesions do not typically resolve spontaneously, and definitive treatment involves complete removal.[3] Newer approaches, such as carbon dioxide laser therapy, have shown promising cosmetic outcomes for multiple lesions.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The primary cause of steatocystoma remains unclear; however, its pathogenesis is thought to involve genetic mutations, specifically in the keratin 17 (KRT17) gene, which plays a crucial role in the structural integrity of epithelial cells. This theory is further supported by the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern observed in many cases of steatocystoma multiplex, in which aberrations in the KRT17 gene have been identified as the key mutation.[4]

Steatocystomas may also be associated with other conditions. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with pachyonychia congenita type 2 (Jackson-Lawler syndrome), onychodystrophy, natal teeth, a painful palmoplantar keratoderma, or eruptive vellus hair cysts.[5][6] Although steatocystoma multiplex is often inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait, isolated lesions are frequently sporadic and can arise without a genetic predisposition, possibly due to environmental factors or skin trauma. An earlier hypothesis, known as the retention cyst theory, suggested that sebaceous duct blockage by a keratinous plug could lead to cyst formation. However, this theory has been largely discredited, as histopathological studies have consistently failed to identify such blockages.[3]

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of steatocystoma in the general population is not well-documented. An overwhelming predilection for any particular gender or ethnic group is not generally noted.[3] Steatocystomas are most commonly observed in the second and third decades of life but can occur at any age, from birth to late adulthood.[7] Rare cases of an acral subcutaneous variant of steatocystoma multiplex have been described, showing a notable female predominance.[8] As previously mentioned, steatocystoma multiplex often occurs in successive generations within the same family, consistent with the proposed autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern.[9]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of steatocystoma is partially attributed to the abnormal development and functioning of sebaceous glands. Some researchers hypothesize that cyst formation arises due to the atypical dilation of the sebaceous duct, which leads to sebum accumulation.[10] On the other hand, evidence suggests that the primary cause is linked to mutations in KRT17, primarily located in the basal cells of epithelial tissues and plays a critical role in cell proliferation, growth, skin inflammation, and hair follicle cycling.[11]

The overexpression of KRT17 is linked to the development of steatocystomas, and genetic mutations in the KRT17 gene are associated with steatocystoma multiplex and pachyonychia congenita type 2. More specifically, pachyonychia congenita type 2 results from mutations in both keratin 6b and KRT17; patients with this disorder present with various cysts derived from the pilosebaceous unit, including steatocystomas.[12] Although the precise mechanism connecting KRT17 mutations to pachyonychia congenita is not fully understood, its compromised function in pilosebaceous and glandular structures contributes to cyst formation.[11]

Histopathology

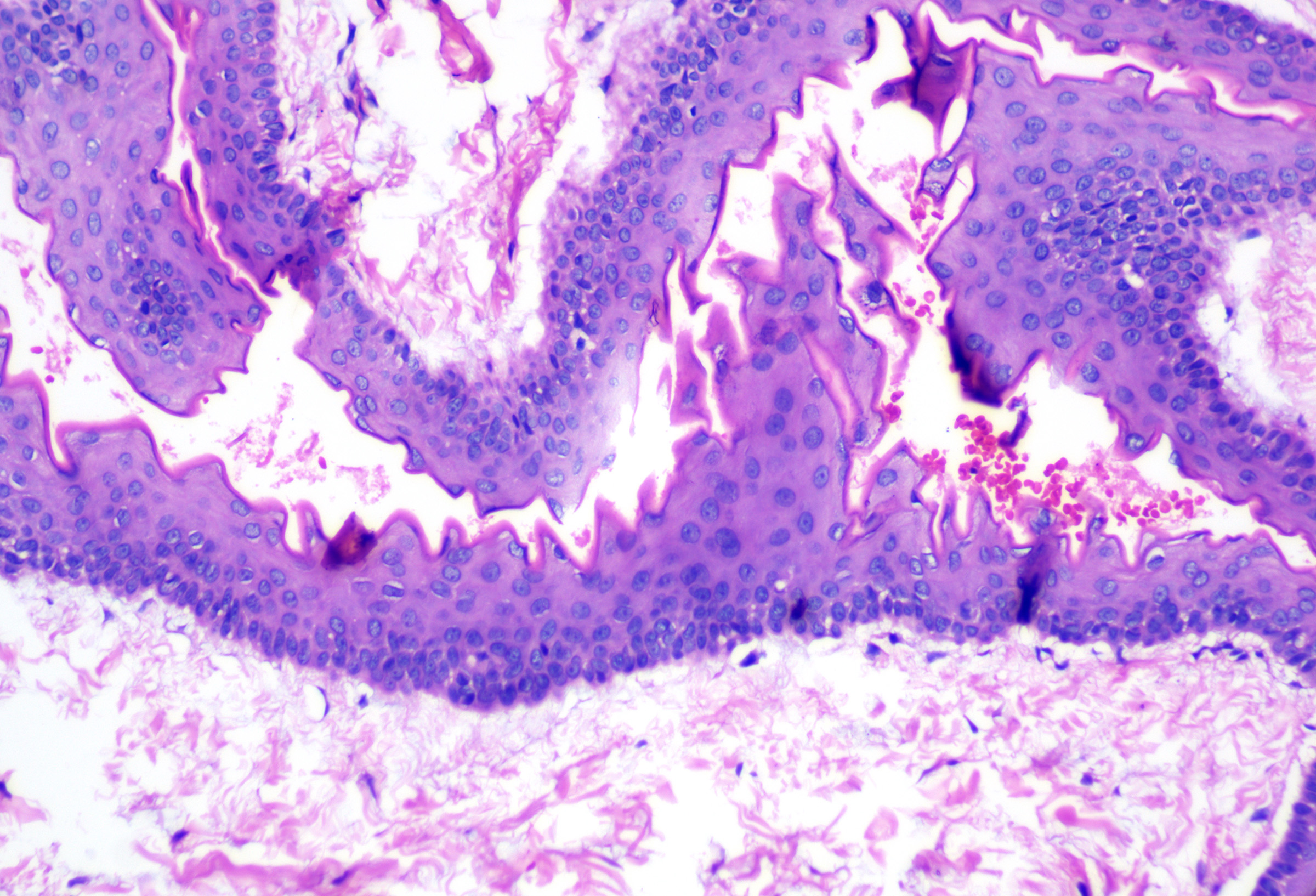

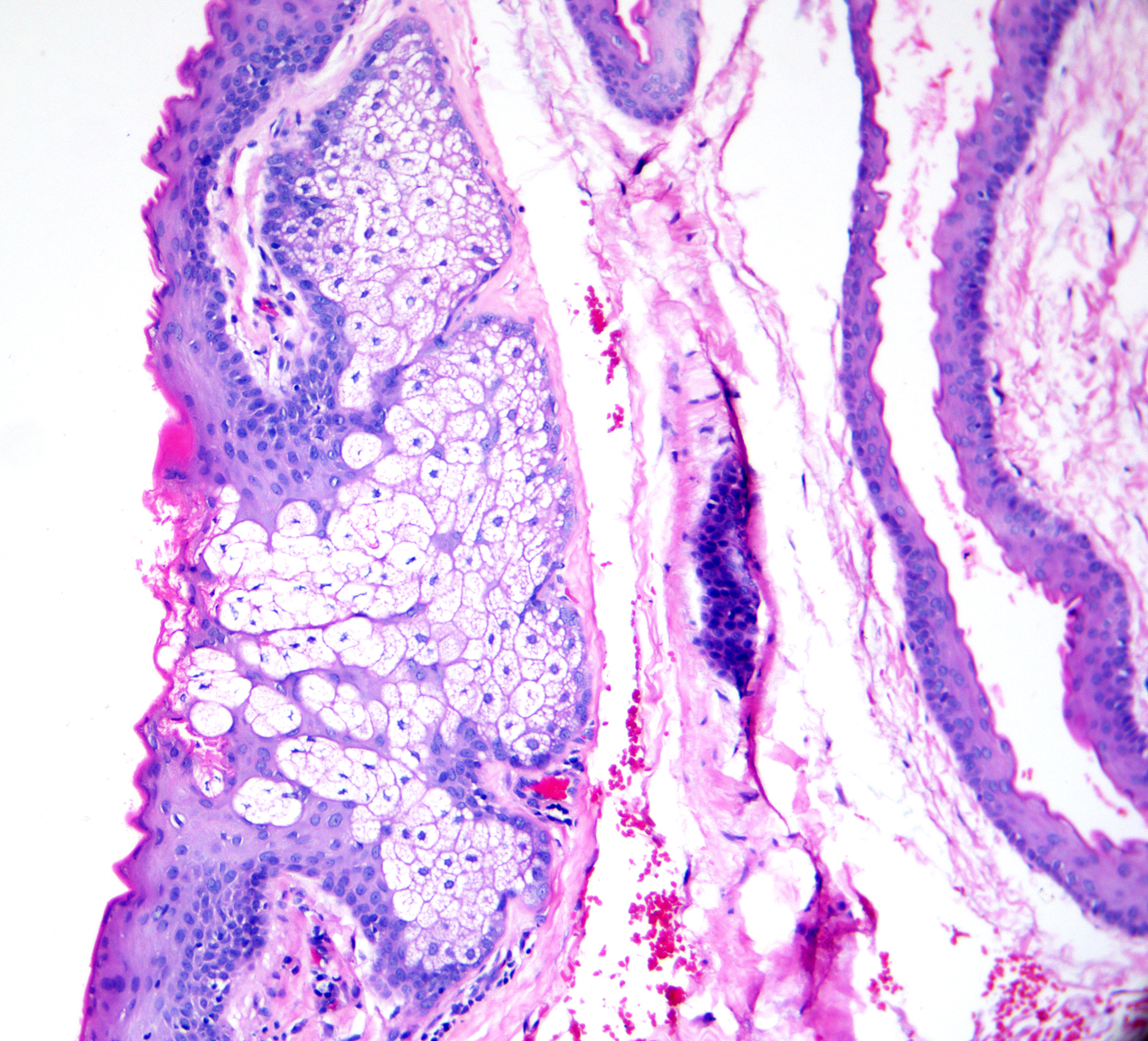

Unlike the commonly incorrect label applied to epidermal inclusion cysts, steatocystomas are true sebaceous cysts as they contain sebaceous glands within the cyst wall. On microscopic examination, the cyst's lining comprises thin stratified squamous epithelium, often with a reduced or completely absent granular layer. This configuration generally results in a collapsed, empty cystic cavity; however, sebum and keratin may also be observed within the lumen.[13]

Classically, the cyst wall has a glassy, eosinophilic cuticle with an undulating and wavy shark-tooth appearance (see Image. Steatocystoma). This unique lining and sebaceous glands within the cyst wall are the hallmark features of steatocystoma that differentiate this entity from other cystic formations (see Image. Steatocystoma Cuticle).[14] In many cases, vellus hairs or smooth muscle bundles are found within the cyst or the surrounding tissue.[15]

Immunohistochemical staining, although not mandatory for diagnosis, can also offer valuable supporting evidence. Studies on the staining patterns of steatocystomas have shown the expression of both keratin 10 and keratin 17.[16] Furthermore, lipid-specific stains such as adipophilin can aid in confirming the presence of sebocytes and sebaceous glands within the cyst lining.[17]

History and Physical

Most steatocystomas emerge sporadically and present as a singular lesion known as steatocystoma simplex. Less commonly, patients may develop multiple steatocystomas, particularly those with a familial predisposition following an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, termed steatocystoma multiplex.[18]

Individuals with steatocystoma often notice the gradual appearance of smooth, round, and mobile nodules that vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters.[19] These lesions frequently develop during adolescence and early adulthood, coinciding with the increased growth and activity of sebaceous glands. Steatocystomas can occur across various anatomical sites, with a distinct predilection for areas rich in sebaceous glands, such as the chest, axillae, and groin.[1]

These cysts are typically confined to the dermal layer of the skin; however, more superficial lesions tend to have a yellowish hue, whereas deeper ones are typically skin-colored. Although typically asymptomatic, these cysts can release an odorless, oily fluid if punctured.[3] When multiple steatocystomas are observed on physical examination or the patient is found to have coexisting congenital abnormalities, these could be signs of familial steatocystoma multiplex or a broader genetic disorder, such as pachyonychia congenita. Consequently, this should prompt an investigation into the family history for similar lesions or consideration of genetic testing.[18]

Evaluation

Dermoscopic Evaluation

The evaluation of steatocystoma begins with a comprehensive medical history and a thorough physical examination; however, the exam findings are generally nonspecific, manifesting as painless, smooth, skin-colored nodules.[19] Consequently, many other entities can potentially serve as mimickers, and steatocystomas are frequently mistaken for more common cystic lesions, such as epidermal inclusion cysts, during clinical evaluation.[20]

Dermoscopic examination of suspected steatocystomas may offer valuable insights and help to increase diagnostic accuracy. However, its effectiveness is currently limited due to the scarcity of reported descriptions in the literature. Nonetheless, it may still help distinguish steatocystomas from other cystic lesions. Several case reports have described the dermoscopy findings in steatocystomas as having yellow, creamy, structureless areas and diffuse margins, which are believed to correspond to the sebum within the cyst cavity.[21]

Ultimately, diagnostic confirmation relies on biopsy and histopathological analysis. If the pathognomonic features are observed and microscopic examination reveals a cystic structure with a thick, eosinophilic cuticle devoid of a granular layer and the presence of sebaceous glands within the cyst wall lining, then a definitive diagnosis of steatocystoma can be made.[3]

Additional Diagnostic Studies

Standard diagnostic evaluations, such as laboratory tests or radiographic imaging, are rarely used besides histopathological examination. However, steatocystomas are often identified incidentally on imaging, and imaging studies have previously been used as a noninvasive tool to help differentiate steatocystoma multiplex from other conditions.[22] Numerous case reports have described the detection of steatocystomas on routine mammography, presenting as multiple cystic structures with a central fat density.[23] In contrast, ultrasound imaging classically demonstrates anechoic cysts with posterior acoustic enhancement.[24] In addition, patients with steatocystoma multiplex have also undergone magnetic resonance imaging, revealing unilocular, hyperintense cystic lesions.[25]

Treatment / Management

Medical Management

Steatocystomas are benign cysts without any potential for malignancy. These cysts generally do not require intervention after diagnosis. Although typically unnecessary, treatment may be considered when the diagnosis is unclear despite histopathological examination or the patient seeks removal for cosmetic concerns. When considering treatment options for steatocystoma multiplex, the approach to management can be broadly subdivided into medical and procedural. Surgical interventions may be reasonable for isolated or singular lesions. However, less invasive methods may be warranted for patients with numerous lesions to avoid scarring and procedural complications.[3]

The most commonly prescribed medical treatment is oral isotretinoin, which effectively reduces the size of existing cysts and prevents new ones. Despite its benefits, it has demonstrated high recurrence rates, limited success in treating inflamed lesions, and initial exacerbations of the disease.[26] Alternative medical therapies include oral tetracyclines or topical clindamycin, which can be effective for the suppurative variant, although their effectiveness is limited.[27]

Procedural Therapies

Procedural management options include cryotherapy, needle aspiration, and surgical excision. Cryotherapy has shown some benefit when treating multiple lesions in a single session and is potentially suitable for larger lesions. However, it has relatively low cure rates, and repeated treatments can result in cosmetic disfigurement, blister formation, scarring, and hypopigmentation.[28] Needle aspiration is another procedural option that is cost-effective and well-tolerated but has been associated with a high recurrence rate.[29][30] Lastly, surgical excision, which entails the complete removal of the cyst wall, has a very low risk of recurrence and was once the most widely practiced method. However, due to its time-intensive nature and high potential for scarring, this method has become less favored for widespread lesions in recent years, prompting the use of alternative methods.[31](B3)

Recently, carbon dioxide laser therapy has emerged as a treatment option that effectively manages multiple lesions in a single session, resulting in excellent cosmetic outcomes.[32] This approach may not be appropriate for larger cysts and is not widely available to all patients. Notably, the recurrence rates with this laser method are comparable to those of excision but without cosmetic drawbacks.[33][34]

Differential Diagnosis

Various cystic conditions or subcutaneous tumors can present similarly to steatocystoma, as they often manifest as painless, skin-colored to yellow nodules. Although not comprehensive, the clinical differential diagnosis includes lipomas, epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and eruptive vellus hair cysts.[20]

Acneiform cysts, especially those linked to severe acne, can also mimic steatocystomas. However, acne cysts typically appear in clusters and are often accompanied by other acne characteristics, such as comedones and pustules. These cysts also fluctuate in size and are prone to inflammation, whereas steatocystomas tend to remain stable and exhibit less inflammatory activity. Further biopsy and histological examination are required to achieve a definitive diagnosis and distinguish between these conditions.[7]

Many entities may resemble steatocystomas under microscopic examination. The histological differential diagnoses include:

- Epidermoid cysts: These cysts often exhibit similar histological features; however, they are distinguishable by the presence of more substantial keratin debris within the central cavity and the absence of a pink cuticle or sebaceous glands in the cyst wall.[20]

- Vellus hair cysts: These lesions contain small vellus hairs within the cyst cavity, forming large epidermoid cysts with multiple vellus hairs. In contrast, steatocystomas generally appear as empty cysts.[35]

- Dermoid cysts: These cysts may also resemble steatocystoma and commonly contain pink-colored cuticles and sebaceous glands. However, they are defined by a complete spectrum of adnexal structures in the cyst wall, including follicles, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands.[36]

- Cutaneous keratocysts: Cutaneous keratocysts typically have a similar corrugated, eosinophilic lining with a stratified squamous epithelium and an absent granular layer. However, unlike steatocystomas, keratocysts typically lack adnexal structures.[37]

- Hidrocystomas: These lesions may be mistaken for steatocystomas, but hidrocystomas generally present with a 2-cell-layer thick cuboidal lining and contain amorphous sweat-gland material within the central cavity.[38]

Prognosis

The prognosis for steatocystoma is excellent, as the condition is benign. To date, there have been no documented cases of malignant transformation.[39] No treatment is required, and the prognosis for steatocystoma is favorable. Steatocystomas generally persist over time, and spontaneous resolution is not expected. If patients elect to treat for symptomatic relief or cosmetic concerns, recurrence rates are relatively high. New cysts can continue to develop throughout the patient's life.[40]

Complications

Most complications associated with steatocystoma are cosmetic and psychological rather than physical. In patients with widespread cysts, the condition can cause significant disfigurement.[41] Complications of steatocystoma can include cyst rupture, inflammation, secondary infection, and calcification.[42] In rare instances, an infected steatocystoma may lead to pain, scarring, and sinus tract formation. In addition, rare cases of patients with steatocystoma multiplex experiencing simultaneous inflammation of multiple lesions have been documented. This inflammation can rarely lead to extensive sinus tract formation and scarring, considerably impacting the patient's quality of life. A cohort of researchers has posited that these severe manifestations should be considered a separate variant, introducing the term steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa to describe this subset of patients.[43]

As previously discussed, various treatments for steatocystomas are available, each with different recurrence rates and associated risks. Systemic therapies, such as isotretinoin, and minimally invasive techniques, such as needle aspiration, help minimize scarring but tend to have high recurrence rates.[14] In contrast, methods that involve destruction or complete cyst wall removals, such as elliptical excision or punch excision, show significantly lower recurrence but require more time and can result in complications such as scarring, infection, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation.[40]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should emphasize the benign nature of the condition and the potential for recurrence. Patients should be advised to avoid manipulating or attempting to drain the cysts themselves to prevent infection and scarring. Evaluation or intervention is generally not required for patients with sporadic and isolated lesions. With isolated lesions, no associated symptoms or systemic findings are expected.[28]

For patients with multiple steatocystomas or those presenting with congenital abnormalities on physical examination, further medical evaluation is warranted. These findings may point to familial steatocystoma multiplex or a more extensive genetic disorder, such as pachyonychia congenita. Further family historical information, including similar findings in family members or genetic testing, should be explored in such cases. Genetic counseling may be beneficial for individuals with a family history of steatocystoma multiplex. Regular follow-ups with a dermatologist can help manage new cysts and address any complications promptly.[18] Any patient presenting with new, unexplained skin growths should be referred for dermatologic evaluation. Following the histological confirmation of steatocystoma, patients can be reassured that the condition is benign. Subsequently, various treatment options can be offered if the patient expresses the desire for removal, bearing in mind that more lesions may appear over time.[44]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of steatocystomas involves a collaborative interprofessional approach to improve patient-centered care, enhance outcomes, ensure safety, and optimize team performance. Clinicians and advanced practitioners play a critical role in diagnosing and differentiating steatocystomas through clinical examinations, dermoscopy, biopsies, and histopathological analysis. Nurses are integral in delivering patient education, providing wound care, monitoring recovery, and ensuring patients feel supported throughout their care journey. Pharmacists and dermatology clinicians guide medication management, particularly for treatments such as oral isotretinoin or antibiotics, optimizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Personalized treatment strategies are essential, with surgical excision prioritized for isolated lesions and less invasive methods used for multiple lesions to reduce complications such as scarring.

Ethical considerations are paramount, emphasizing informed consent and patient autonomy. Providing comprehensive information about the condition, available treatments, and recurrence risks fosters trust, enhances patient satisfaction, and encourages adherence to management plans. Interprofessional communication and care coordination are vital for seamless care delivery. Regular team meetings and case discussions allow for the exchange of critical information, resolution of concerns, and collaborative decision-making, ensuring patients receive timely follow-up care and monitoring for recurrence or complications.

Healthcare teams can effectively manage steatocystomas by leveraging each team member's unique skills, promoting open communication, and focusing on patient-centered care. This collaborative effort enhances patient safety and satisfaction and strengthens team performance, ensuring high-quality, comprehensive care for individuals with this condition. Robust care coordination further minimizes errors, reduces delays, and ensures continuity from diagnosis to follow-up, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kamra HT, Gadgil PA, Ovhal AG, Narkhede RR. Steatocystoma multiplex-a rare genetic disorder: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2013 Jan:7(1):166-8. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4691.2698. Epub 2013 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 23449619]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim SJ, Park HJ, Oh ST, Lee JY, Cho BK. A case of steatocystoma multiplex limited to the scalp. Annals of dermatology. 2009 Feb:21(1):106-9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.1.106. Epub 2009 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 20548872]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePalaniappan V, Karthikeyan K. Steatocystoma Multiplex. Indian dermatology online journal. 2024 Jan-Feb:15(1):105-112. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_490_23. Epub 2023 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 38283021]

Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, Paller AS, Munro CS, Jonkman MF, Uitto J, McLean WH. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. The British journal of dermatology. 1998 Sep:139(3):475-80 [PubMed PMID: 9767294]

Sharma VM, Stein SL. A novel mutation in K6b in pachyonychia congenita type 2. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2007 Aug:127(8):2060-2 [PubMed PMID: 17429440]

McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, Morley SM, Lane EB, Swensson O, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, Griffiths WA, Eady RA, Higgins C. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nature genetics. 1995 Mar:9(3):273-8 [PubMed PMID: 7539673]

Varshney M, Aziz M, Maheshwari V, Alam K, Jain A, Arif SH, Gaur K. Steatocystoma multiplex. BMJ case reports. 2011 Sep 26:2011():. doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4165. Epub 2011 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 22679266]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJain M, Puri V, Katiyar Y, Sehgal S. Acral steatocystoma multiplex. Indian dermatology online journal. 2013 Apr:4(2):156-7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.110644. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23741681]

Marasca C, Megna M, Donnarumma M, Fontanella G, Cinelli E, Fabbrocini G. A Case of Steatocystoma Multiplex in a Psoriatic Patient during Treatment with Anti-IL-12/23. Skin appendage disorders. 2020 Sep:6(5):309-311. doi: 10.1159/000507657. Epub 2020 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 33088817]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKohsa K, Yamada H, Sugihara H. Influence of air exposure treatment on alveolar type II epithelial cells cultured on extracellular matrix. Cell structure and function. 1996 Feb:21(1):81-9 [PubMed PMID: 8726477]

Yang L, Zhang S, Wang G. Keratin 17 in disease pathogenesis: from cancer to dermatoses. The Journal of pathology. 2019 Feb:247(2):158-165. doi: 10.1002/path.5178. Epub 2018 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 30306595]

Morais P, Peralta L, Loureiro M, Coelho S. Pachyonychia congenita type 2 (Jackson-Lawler syndrome) or PC-17: case report. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2013:21(1):48-51 [PubMed PMID: 23683487]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShin NY, Kang JH, Kim JE, Symkhampa K, Huh KH, Yi WJ, Heo MS, Lee SS, Choi SC. Steatocystoma multiplex: A case report of a rare entity. Imaging science in dentistry. 2019 Dec:49(4):317-321. doi: 10.5624/isd.2019.49.4.317. Epub 2019 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 31915618]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGordon Spratt EA, Kaplan J, Patel RR, Kamino H, Ramachandran SM. Steatocystoma. Dermatology online journal. 2013 Dec 16:19(12):20721 [PubMed PMID: 24365012]

Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. The Journal of dermatology. 2002 Mar:29(3):152-6 [PubMed PMID: 11990250]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTomková H, Fujimoto W, Arata J. Expression of keratins (K10 and K17) in steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive vellus hair cysts, and epidermoid and trichilemmal cysts. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 1997 Jun:19(3):250-3 [PubMed PMID: 9185910]

Ostler DA, Prieto VG, Reed JA, Deavers MT, Lazar AJ, Ivan D. Adipophilin expression in sebaceous tumors and other cutaneous lesions with clear cell histology: an immunohistochemical study of 117 cases. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2010 Apr:23(4):567-73. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.1. Epub 2010 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 20118912]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHurley HJ, LoPresti PJ. Steatocystoma Multiplex. Archives of dermatology. 1965 Jul:92(1):110-1 [PubMed PMID: 11850944]

Ogawa Y, Nogita T, Kawashima M. The coexistence of eruptive vellus hair cysts and steatocystoma multiplex. The Journal of dermatology. 1992 Sep:19(9):570-1 [PubMed PMID: 1479117]

Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008 Dec:59(6):1050-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.034. Epub 2008 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 18819726]

Sharma A, Agrawal S, Dhurat R, Shukla D, Vishwanath T. An Unusual Case of Facial Steatocystoma Multiplex: A Clinicopathologic and Dermoscopic Report. Dermatopathology (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Apr-Jun:5(2):58-63. doi: 10.1159/000488584. Epub 2018 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 29998099]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChotai N, Lim SK. Imaging features of steatocystoma multiplex- back to basics. The breast journal. 2021 Apr:27(4):389-390. doi: 10.1111/tbj.14179. Epub 2021 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 33527591]

Pollack AH, Kuerer HM. Steatocystoma multiplex: appearance at mammography. Radiology. 1991 Sep:180(3):836-8 [PubMed PMID: 1871303]

Arceu M, Martinez G, Alfaro D, Wortsman X. Ultrasound Morphologic Features of Steatocystoma Multiplex With Clinical Correlation. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2020 Nov:39(11):2255-2260. doi: 10.1002/jum.15320. Epub 2020 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 32356597]

Shamloul G, Khachemoune A. An updated review of the sebaceous gland and its role in health and diseases Part 1: Embryology, evolution, structure, and function of sebaceous glands. Dermatologic therapy. 2021 Jan:34(1):e14695. doi: 10.1111/dth.14695. Epub 2021 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 33354858]

Rosen BL, Brodkin RH. Isotretinoin in the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a possible adverse reaction. Cutis. 1986 Feb:37(2):115, 120 [PubMed PMID: 3456886]

Adams B, Shwayder T. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum. International journal of dermatology. 2008 Nov:47(11):1155-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03698.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18986448]

Georgakopoulos JR, Ighani A, Yeung J. Numerous asymptomatic dermal cysts: Diagnosis and treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2018 Dec:64(12):892-899 [PubMed PMID: 30541803]

Oertel YC, Scott DM. Cytologic-pathologic correlations: fine needle aspiration of three cases of steatocystoma multiplex. Annals of diagnostic pathology. 1998 Oct:2(5):318-20 [PubMed PMID: 9845756]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, Friedman PM. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2012 Jul:38(7 Pt 1):1104-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02391.x. Epub 2012 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 22487444]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePamoukian VN, Westreich M. Five generations with steatocystoma multiplex congenita: a treatment regimen. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1997 Apr:99(4):1142-6 [PubMed PMID: 9091916]

Krähenbühl A, Eichmann A, Pfaltz M. CO2 laser therapy for steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatologica. 1991:183(4):294-6 [PubMed PMID: 1809593]

Kassira S, Korta DZ, de Feraudy S, Zachary CB. Fractionated ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of steatocystoma multiplex. Journal of cosmetic and laser therapy : official publication of the European Society for Laser Dermatology. 2016 Nov:18(7):364-366 [PubMed PMID: 27183246]

Bakkour W, Madan V. Carbon dioxide laser perforation and extirpation of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2014 Jun:40(6):658-62. doi: 10.1111/dsu.0000000000000013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24852470]

Anand P, Sarin N, Misri R, Khurana VK. Eruptive Vellus Hair Cyst: An Uncommon and Underdiagnosed Entity. International journal of trichology. 2018 Jan-Feb:10(1):31-33. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_61_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29440857]

Dillon JR, Avillo AJ, Nelson BL. Dermoid Cyst of the Floor of the Mouth. Head and neck pathology. 2015 Sep:9(3):376-8. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0576-y. Epub 2014 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 25351706]

Cassarino DS, Linden KG, Barr RJ. Cutaneous keratocyst arising independently of the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2005 Apr:27(2):177-8 [PubMed PMID: 15798450]

Charles NC, Kim ET. Eccrine Cyst (Hidrocystoma) of the Inner Canthus: A Rare Entity With Immunohistologic Confirmation. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2023 May-Jun 01:39(3):e96-e97. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002349. Epub 2023 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 36806128]

Gargya V, Lucas HD, Wendel Spiczka AJ, Mahabir RC. Is Routine Pathologic Evaluation of Sebaceous Cysts Necessary?: A 15-Year Retrospective Review of a Single Institution. Annals of plastic surgery. 2017 Feb:78(2):e1-e3. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000826. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27070686]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoudhary S, Koley S, Salodkar A. A modified surgical technique for steatocystoma multiplex. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2010 Jan:3(1):25-8. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.63284. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20606990]

Keefe M, Leppard BJ, Royle G. Successful treatment of steatocystoma multiplex by simple surgery. The British journal of dermatology. 1992 Jul:127(1):41-4 [PubMed PMID: 1637693]

Rahman MH, Islam MS, Ansari NP. Atypical steatocystoma multiplex with calcification. ISRN dermatology. 2011:2011():381901. doi: 10.5402/2011/381901. Epub 2011 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 22363850]

Atzori L, Zanniello R, Pilloni L, Rongioletti F. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativa associated with hidradenitis suppurativa successfully treated with adalimumab. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2019 Oct:33 Suppl 6():42-44. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15848. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31535759]

Varde MA, Heindl LM, Kakkassery V. [Diagnosis and treatment of benign eyelid tumors]. Die Ophthalmologie. 2023 Mar:120(3):240-251. doi: 10.1007/s00347-022-01798-x. Epub 2023 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 36763162]