Introduction

Genitofemoral neuralgia is a chronic, painful neuropathic condition caused by compression or trauma to the genitofemoral nerve and its branches.[1] This condition usually presents with constant burning pain or discomfort in the inguinal region, along with hyperalgesia or anesthesia in the genitals and inner thighs.[2] Genitofemoral neuralgia is a common cause of groin pain in both female and male patients, particularly after recent or previous surgical interventions that may have inadvertently damaged the genitofemoral nerve.[1][3]

Magee first described this condition in 1942 as causalgia instead of neuralgia, as seen as a complication of appendicular surgery.[4] Lyon renamed it genitofemoral neuralgia 3 years later, given its unique pain characteristics and cutaneous distribution.[1] The genitofemoral nerve originates from the first 2 lumbar roots (L1 and L2).[1] The nerve trunk then pierces the psoas muscle at the level of the third and fourth lumbar spine vertebrae, descending to the inguinal region along the anterior surface of the muscle. This trajectory makes it susceptible to injury from overly aggressive traction. The nerve passes under the ureter and bifurcates into the genital and femoral branches, which cross the inguinal ligament to enter the deep inguinal ring. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Genitofemoral Nerve," for more information.

The 2 branches usually follow separate and distinct anatomical courses after emerging on the surface of the psoas muscle.[1][2]

- In males, the genital branch travels along the spermatic cord through the inguinal canal to innervate the cremaster muscle and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Additionally, the genital nerve provides sensory innervation to the spermatic cord, lateral scrotum, and the adjacent ventromedial aspect of the thigh. The femoral branch provides purely sensory innervation to the skin of the upper anterior thigh.

- In females, the genital branch travels alongside the round ligament to provide sensory innervation to the labia majora and mons pubis.[1] The femoral branch of the nerve does not enter the inguinal canal; it travels under the inguinal ligament and externally to the femoral sheath.

The femoral branch is the most lateral structure within the femoral triangle, which also contains the femoral vessels and the lymph node of Cloquet. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Femoral Triangle," "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Lymphatic Drainage," and "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inguinal Lymph Node," for more information. This nerve provides sensory innervation to the superior proximal anterior aspect of the thigh, lateral and anterior to the area covered by the ilioinguinal nerve.[1] This nerve is susceptible to injury during procedures requiring femoral vein access, particularly if complicated by aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, vessel perforations, or extensive dissection.[1]

Additionally, oncological metastatic diseases such as sarcomas, femoral bone fractures, and orthopedic interventions can damage the nerve, causing sensory impairment.[1][5] In some patients, the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve might have an overlapping sensory innervation with the lateral femoral nerve, which can further hinder and delay correct diagnosis.[1]

The cremasteric reflex is produced through an afferent pathway innervated by the ilioinguinal nerve and the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve and an efferent pathway innervated by the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve.[6] The innervation of the afferent pathway has been contradictory, and no electrophysiological studies have been done to confirm results.

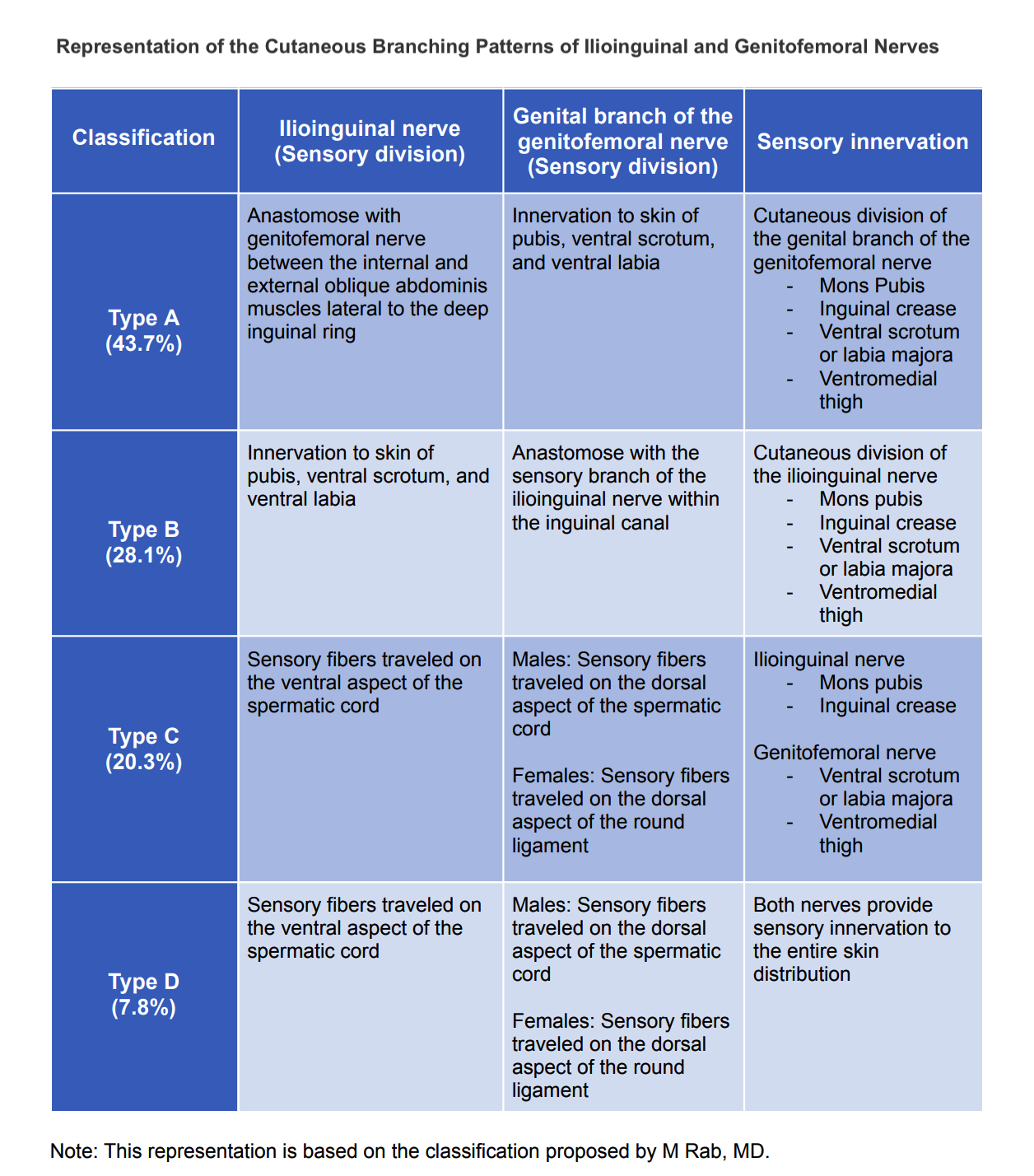

The anatomical distribution of the genitofemoral nerve, as in any other structure, is subjected to different anatomical variants.[1] In 2001, Rab et al described the variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. This anatomical variability has significant implications for surgical planning and interventions.[2] Additionally, awareness of known variants improves accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment of patients suffering from neuralgia.

Rab et al categorized the different anatomical variants of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves using the letters A through D. The most common anatomical distribution described in the literature follows Rab’s type C classification of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves (see Image. Anatomical Variations of Sensory Innervations).[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Genitofemoral neuralgia is most commonly iatrogenic in the setting of recent surgical interventions.[1] The most frequent surgical procedures associated with genitofemoral nerve injury are appendectomy, cesarean section, lymph node biopsy or resection, hysterectomy, vasectomy, inguinal herniorrhaphy, nephrectomy, and urethrectomy.[7][8] Among these, laparoscopic and especially open herniorrhaphies have the highest incidence of genitofemoral neuralgia.

Noopur reported that neuropathic groin pain is the most common postoperative complication in patients undergoing open inguinal hernia repair.[9] Scars from these procedures, especially from an open appendectomy, can lead to nerve entrapment or compression, with a decreased incidence in laparoscopic procedures.[1] However, procedures requiring mesh placement or tension-free repairs, such as herniorrhaphy, are most likely to cause genitofemoral irritation through nerve tethering, entrapment, or direct damage, regardless of the surgical approach.[10][11]

Excessive retraction of the psoas muscle may injure the genitofemoral and femoral cutaneous nerves that lie on the muscle surface. These nerves may also be inadvertently injured during an external lymph node dissection or any procedure involving surgical mobilization or skeletonization of the iliac vessels. Additionally, the formation of a meshoma or infection of the surgical mesh can lead to nerve injury or neuritis.[11] Therefore, the use of mesh requires surgeons to have adequate surgical planning and understand mesh fixation techniques when performing abdominopelvic surgeries to decrease the risk of such neuropathic complications.[7][12]

Posterior mesh placement and avoidance of the deep cremasteric fascia, which serves as a barrier to the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, substantially decrease the risk of periprocedural nerve damage.[12] About 63% of post-herniorrhaphy patients develop chronic neuropathic pain likely from scar-related nerve entrapment or accidental nerve ligation with subsequent neuroma development.[3][11]

Direct retroperitoneal nerve compression can occur in patients with psoas muscle abscess, retroperitoneal hematoma, or Pott disease, potentially presenting as genitofemoral neuralgia.[4] Additionally, direct abdominal trauma, visceral adhesions, third-trimester pregnancy, and malignancy have been documented as causes of genitofemoral nerve entrapment.[13]

Indirect nerve damage has been documented in inflammatory diseases where granulomatous processes compress the genitofemoral nerve or its branches.[14] Although less common, nerve compression can also occur in patients who perform repetitive hip motions, such as bicycling, or who are exposed to prolonged abdominal compression.[1][13][15][16]

Epidemiology

Recent literature does not provide specific data on the incidence of genitofemoral neuralgia.[13] However, in 2009, Bohrer et al reported a 1.8% incidence of nonspecific neuropathic pain after gynecological surgeries, while Honig reported a similar rate, with 73% of patients experiencing full recovery.[17][18] The overall incidence of nerve injury following pelvic surgery has been reported as 2%.[17][19] Genitofemoral neuralgia has been shown to have an equal overall incidence in both genders.[3]

History and Physical

Genitofemoral neuralgia commonly presents with constant or intermittent burning pain or discomfort in the lower lateral abdomen or, more typically, the ipsilateral inguinal region.[1] This pain may extend to the anteromedial upper thigh and the ipsilateral scrotum or labia majora.[1][20] The pain is often aggravated by walking, bicycling, Valsalva maneuvers, or hip and thigh hyperextension.[1][20] Palpation of the pubic tubercle is typically painful.[1][20] The pain can be alleviated by sitting, lying in a recumbent position, flexing the hip, or assuming a bent-over position while standing.[1][20] The onset of discomfort can vary, starting immediately after surgery or being delayed for months or even years.

This condition is usually associated with ipsilateral anesthesia of the superior medial thigh and genitalia, hyperalgesia along the nerve distribution, paresthesias, allodynia, and point tenderness on palpation of the inguinal ligament.[1][20] Female patients typically report a burning sensation on the labia majora and medial thigh, while males usually experience scrotal pain. Tactile sense assessment often reveals hypoesthesia to soft touch and hyperesthesia or allodynia to sharp contact in the affected nerve distribution, compared to the contralateral side.[21] Hip extension, bicycling, and tight clothing tend to worsen the discomfort.

An accurate diagnosis of genitofemoral neuralgia requires a thorough history and physical examination. Symptoms may develop immediately after surgery or not several years later. Healthcare professionals caring for patients with suspected genitofemoral neuralgia should consider the following points during the history-taking process: [1]

- The characteristics and distribution of the pain should be obtained. Patients typically describe neuropathy as a burning or shooting pain, but it may also present as itching, tingling, stabbing, or sharp pain.

- The presence or absence of numbness or hyperalgesia should be explored and documented.

- The inciting event and the progression of symptoms over time must be identified.

- Alleviating and aggravating factors should be recognized.

- Any previous history of surgical procedures or trauma to the area should be identified. If a surgical procedure was reported, details of the operation performed, the surgical approach (open versus laparoscopic), perioperative pain, and postoperative complications should be documented.

- Recent illnesses, surgeries, or travel should be inquired about.

- Recent pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments should be explored.

- A history of diagnosed chronic pain syndrome, malignancies, chemotherapy, radiation therapy exposure, and abdominal trauma should also be inquired about.

Physical examination is a crucial component of assessing neurological conditions such as neuralgias. A thorough understanding of human anatomy and nerve distribution enables physicians to diagnose genitofemoral neuralgia without relying on alternative diagnostic tools. The following recommendations are suggested for clinicians performing the examination:[1]

- The examination should be performed bilaterally.

- A complete skin inspection and palpation should be performed. Areas of skin irritation, rash, tenderness, open wounds, induration, or inflammation should be identified. Point tenderness near the inguinal ligament may be observed.

- A tactile sense assessment, including evaluations of crude touch and pinprick sensation, is essential for recognizing dermatomal distributions. Patients may exhibit tenderness upon palpation of the inguinal region, with neuropathic shooting pain reproduced during the performance of the Tinel sign. The Tinel sign involves tapping on a nerve, which produces a "pins and needles" sensation in the distal distribution of that nerve, indicating peripheral nerve injury. (Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Hoffmann Tinel Sign," for more information.)

- A motor examination should be performed to evaluate all muscle groups. While weakness is not a common feature of genitofemoral neuralgia, patients may present with pain-limited weakness. Testing the spine, hip, and lower limb range of motion must be considered to identify potential aggravating and alleviating positions.

- A straight leg raise test should be conducted to rule out radiculopathy, a Patrick test should be considered to assess for possible hip joint pain, and a Gaenslen test should be performed to evaluate sacroiliac joint integrity.

- Deep tendon reflexes should be evaluated.

- The patient's posture should be evaluated. To minimize abdominal muscle movement, a patient with genitofemoral neuralgia might adopt a hunched position while seated and a flexed position during ambulation.

- The patient's gait should be assessed, and any recent changes should be inquired about. Activities such as fast-paced walking, running, lifting heavy objects, climbing, squatting, or stooping may exacerbate the pain, while lying in the supine position may alleviate the discomfort.[13]

Evaluation

If the clinical history and physical examination cannot differentiate the origin of the neuralgia, selective nerve blocking of the ilioinguinal or genitofemoral nerve is often used to identify the specific source of neuropathic pain.[22][23] The ilioinguinal nerve block is commonly used due to its easy anterior access, whereas the genitofemoral nerve, located in the retroperitoneum and inferior to the inguinal ligament, is less accessible and carries a higher risk of complications.[24]

Imaging alone is generally not helpful in diagnosing genitofemoral neuralgia but can aid in excluding other causes. While blind blocks using anatomical landmarks have been used for years, technological advances now allow for more accurate treatment using ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and x-ray fluoroscopy.[13] Magnetic resonance neurography, in particular, is an emergent tool for diagnosing lumbar neuropathy, providing high-resolution images to reveal any areas of nerve entrapment or damage.[13][25][26]

Ultrasound and 3-Tesla (3-T) magnetic resonance neurography-guided retroperitoneal genitofemoral nerve blocks have been successfully used to diagnose genitofemoral neuralgia, with an overall success rate of approximately 90%.[27]

Electrophysiology is not sensitive enough to diagnose neuralgia. However, somatosensory evoked potentials may offer some benefits in diagnosing genital neuralgia involving the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. The only motor function of the genitofemoral nerve is the efferent limb of the cremasteric reflex, and its absence does not typically affect the patient's quality of life.[13]

Treatment / Management

Healthcare professionals have long struggled to treat patients with neuropathic pain without initially considering a multifaceted, noninvasive approach. Neuropathic symptom management with first-line pharmacological agents is typically necessary for at least 6 to 12 months before any consideration of surgical evaluation. However, clinicians should also explore additional methods of pain control, such as exercises, acupuncture, massage, thermal treatments, physiotherapy, myofascial release, and reflexology.[28] Acupuncture, in particular, has demonstrated effectiveness in improving neuropathic pain, especially following genital surgery.[29][30](A1)

Pharmacological Management

Topical anesthetics, such as lidocaine, menthol, and capsaicin, are commonly used initially for treating neuralgia due to their potential to relieve skin allodynia.[1][31][32][33] However, tricyclic antidepressants are the first line of treatment for any neuropathic pain, including genitofemoral neuralgia.[34][35] Gabapentin, pregabalin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, antiepileptics, N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists, and opioids (especially tramadol) are alternative medications that can improve neuropathic pain.[33][34][35] A 3- to 8-week trial is generally recommended.(A1)

Midway through the treatment period, the effectiveness of the therapy should be reviewed and adjusted or changed as necessary.[33] Combination therapy is encouraged and can be effective, but it increases adverse effects. If initial pharmacological management fails, the next step is usually localized injections.[33]

Nerve block: Injections of local anesthetics and corticosteroids at or proximal to the site of injury are very effective in treating acute neuropathic pain, especially after trauma or surgery, and can provide evidence that a particular nerve is responsible for the discomfort.[36] One commonly used formula is 5 to 10 mL of 0.25% or 0.5% bupivacaine mixed with 20 mg of methylprednisolone or 25 mg of hydrocortisone. A properly performed nerve block provides sustained or permanent relief in some patients. However, the treatment often does not last more than six months and will likely need to be repeated for appropriate pain control.

Nerve ablation (with alcohol, phenol, or other ablative technology) or a neurectomy may then become the best remaining treatment option. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Ablative Nerve Block" and "Phenol Nerve Block," for more information.[37][38] The failure of a properly performed nerve block to control the discomfort, even briefly, strongly suggests some other cause for the pain.(A1)

Ultrasound-guided nerve block injections are available for direct nerve localization after it enters the deep inguinal ring, thus providing better pain control.[8][39] Magnetic resonance neurography–guided retroperitoneal genitofemoral nerve blocks are effective and accurate in diagnosing and treating genitofemoral neuralgia.[27][40][41][42] This technique decreased procedure-related complications and improved therapeutic outcomes in these patients.(B3)

Botulinum toxin type A injected subcutaneously has been reported successful for genitofemoral neuralgia refractory to other measures.[20](B3)

Procedural Interventions

Implantable peripheral nerve stimulation devices have been shown to improve neuropathic pain in up to 70% of patients with genitofemoral neuralgia.[43][44][45] Intraoperative peripheral nerve stimulation is the standard procedure to identify nerve injury by direct stimulation, especially when manipulating a nerve or neural plexus.[46] The absence of the cremasteric reflex in men has been used to identify genitofemoral nerve injury post-stimulation.[46] However, this procedure is often complicated by the formation of hematomas, the need for periodic battery replacement, and device exchanges.[9] A risk of additional trauma during device placement and infection occurs in about 5% of cases, particularly during battery changes. An implanted peripheral nerve stimulator is contraindicated in the presence of a pacemaker.[46](B3)

Radiofrequency ablation is commonly used for long-term neuropathic pain control, leading to thermal damage of the nerve with minimal risk for neuroma formation, as the nerve perineurium and epineurium remain intact. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Radiofrequency Ablation," for more information.[47] Cryoablation is another alternative procedure where the nerve’s axon and myelin sheaths are frozen, resulting in Wallerian degeneration without compromising the perineurium and epineurium layers, thus allowing nerve regeneration with a low risk for neuroma formation. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cryoanalgesia," for more information.[48](B3)

Surgical Management

Neurectomy was reported in the 1940s as an effective treatment for neuropathic symptoms from genitofemoral neuralgia. However, it entails surgical resection of the genitofemoral nerve, an invasive and permanent procedure leading to genital hypoesthesia and loss of the cremasteric reflex. Most patients (about 70%) will experience total relief of their pain, with only some residual cutaneous anesthesia as a permanent adverse effect.[3][49][50](B2)

The retroperitoneal approach is preferred for successful neurectomy because it allows clear visualization of the nerves and accurate identification of the genitofemoral branches. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Genitofemoral Nerve," for more information.[22][51] Triple neurectomy (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) should be considered in post-herniorrhaphy patients who have failed nonsurgical management and had no pain or non-neurogenic pain before herniorrhaphy surgery.[52][53][54][55][56] Retroperitoneal triple neurectomy involves removing the long proximal nerve segments of all three major nerves of the lumbar plexus and inserting nerve endings into the muscles to prevent neuroma formation.[13][52][56] This procedure has shown superiority over other surgical approaches by providing better visualization of neural landmarks and reducing complications from denervation, with an overall success rate of about 70%.[9][57](A1)

If the mesh is identified as the cause of the nerve injury, it should be removed, and a more extensive neurectomy should be performed to prevent the recurrence of symptoms.[58]

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of genitofemoral neuralgia is complicated by the nearby nerves with overlapping cutaneous sensory distributions, particularly the ilioinguinal nerve. Therefore, ilioinguinal neuralgia should always be considered as a potential alternative diagnosis. While most other pelvic neuropathies can be differentiated from genitofemoral neuralgia clinically, the sensory distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve closely resembles and overlaps that of the genitofemoral nerve. Nevertheless, neuropathic pain from genitofemoral neuralgia often presents in the lower abdomen, with characteristic discomfort reproduced upon palpation and hip extension.[32]

Ilioinguinal Neuralgia

This condition is characterized by burning, stabbing pain, and impaired sensation in the lower abdomen and upper thigh. In males, it may affect 11% of post-herniorrhaphy patients, causing a decreased sensation in the anterior scrotal surface and root of the penis. In females, its sensory distribution overlaps with that of the genitofemoral nerve, including the labia majora and mons pubis.[59] Differentiating between ilioinguinal and genitofemoral neuralgia can be challenging, often leading to misdiagnoses and unnecessary surgical interventions.[8] An ilioinguinal nerve block can help distinguish between the 2 conditions, as it is more straightforward to perform than a genitofemoral nerve block. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Ilioinguinal Neuralgia," for more information.[60]

Iliohypogastric Neuralgia

This condition typically presents with burning pain soon after surgery. The pain usually radiates from the abdominal incision site laterally to the suprapubic and inguinal areas. The discomfort may extend into the genitalia, where it can overlap with other neuropathies and complicate accurate diagnosis. While needle electromyography of the lower abdominal muscles may assist in diagnosing iliohypogastric neuralgia, it lacks specificity and sensitivity for a definitive diagnosis.

Pudendal Neuralgia

This condition typically causes chronic pelvic pain that affects the perineal and genital regions. The onset is usually gradual and subtle, with symptoms usually less severe in the morning and worsening throughout the day. Unlike genitofemoral neuralgia, pain from pudendal neuralgia often intensifies with sitting. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Pudendal Neuralgia," for more information.[61] Commonly associated with bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunctions, it is managed with local anesthetic nerve blocks and conservative measures. However, the most effective treatment is often surgical decompression of the nerve.[62][63][64]

Femoral Cutaneous Neuralgia

This condition results in pain and paresthesia affecting the posterolateral and anterior thighs on the affected side.[65] Diagnosis is supported by relief following a local anesthetic block targeting nerve roots L1 and L2.

Obturator Nerve Injury

This condition results in sensory loss in the inner thigh and weakness during thigh adduction, often leading to an abnormal gait.[66] Diagnosis is typically made clinically and can be confirmed with a local anesthetic nerve block.[66] Immediate microscopic surgical repair of a transected obturator nerve provides good recovery of motor function.[67]

Orchalgia or Chronic Testicular Pain

Following hernia surgery, orchalgia is a recognized condition that is frequently misattributed to genitofemoral neuralgia. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Chronic Testicular Pain and Orchalgia," for more information.[68][69][70] Notably, the testes themselves do not have somatic nerve sensations.[58][70][71] The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve affects scrotal sensation, which must be distinguished from orchalgia through a thorough physical examination. If needed, a spermatic cord or other nerve block can help clarify the diagnosis.

Prognosis

The prognosis of genitofemoral neuralgia depends on the duration of symptoms and the extent of nerve damage. Neuropathy is typically caused by nerve compression, leading to neuropraxia. However, neurotmesis, which involves complete nerve transection, can occur as a direct complication of intra-abdominal surgery, significantly impairing the potential for nerve recovery. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Neurotmesis," for more information.[72] The extent and timeline of nerve regeneration vary based on the level of injury, ranging from months to years, with no guarantee of complete nerve recovery or sufficient distal reinnervation.

Patients with neuropathic pain may develop chronic pain syndromes that require a multidisciplinary team approach for effective symptom control. A multifaceted approach to pain management can enhance the improvement of neuropathic symptoms.

Complications

Chronic symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia have detrimental effects on a patient's ability to perform daily life activities. If left untreated, these symptoms may lead to behavioral changes that negatively affect health and social functionality, including medication overuse, excessive calorie consumption, physical inactivity, deconditioning, social isolation, and severe psychological distress.

Surgical management of genitofemoral neuralgia carries inherent risks. Patients must be fully informed about the potential complications of each procedure before giving surgical consent. Peripheral nerve ablation, whether performed through radiofrequency or cryoablation, can result in cell death and tissue damage.

Radiofrequency ablation uses direct high temperatures from radio waves to cause neurolysis of the desired nerve, thus decreasing neuropathic pain. However, this procedure carries risks, including thermal injury to nearby tissues, hematoma formation, infection, and nerve damage. Additionally, the reported complications have been the development of neuritis-related pain and weakness. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Radiofrequency Ablation," for more information.

The most common complication of neurectomy, including triple neurectomy, is hypoesthesia in the areas innervated by the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral nerves, typically without associated muscle weakness. Despite this, triple neurectomy is considered a safe and effective treatment for refractory genitofemoral neuralgia.[73]

Consultations

Consultations for patients with genitofemoral neuropathy are essential for accurate diagnosis, comprehensive treatment planning, and effective management. Multidisciplinary consultations involving primary care physicians, neurologists, pain management specialists, surgeons, and physical therapists offer a holistic approach to patient care. Each specialist contributes their expertise to assess the patient's symptoms, review medical history, and conduct necessary diagnostic tests, such as imaging studies or nerve blocks.

These consultations facilitate the development of tailored treatment plans that may include pharmacological interventions, physical therapy, or surgical options. Regular follow-up consultations are crucial for monitoring the patient's progress, adjusting treatment plans as necessary, and promptly addressing any complications. Collaborative consultations also enhance patient education, ensuring patients understand their condition and actively participate in their care, ultimately improving outcomes and quality of life.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Genitofemoral neuropathy is characterized by injury, compression, or entrapment of the genitofemoral nerve, commonly arising as a complication of abdominal surgery. The extent of nerve injury often correlates with the degree of potential nerve recovery. Untreated neuropathic pain can be significantly life-limiting, adversely affecting a patient’s physical capabilities and lifestyle, and leading to considerable motor and sensory deficits.

Nerve regeneration is often prolonged and cannot be guaranteed, as no current treatments ensure full nerve recovery. However, several patient-specific factors can enhance nerve regrowth and reduce disabilities. Patients should be educated about maintaining strict blood glucose control, as hyperglycemia can further damage peripheral nerves and delay recovery. They should also avoid smoking and alcohol, which can exacerbate neuropathic pain. Weight loss may help reduce the risk of nerve compression, and a diet rich in vitamins and minerals is essential to support adequate nutrition during nerve regeneration and reinnervation.

Patients should maintain a regular exercise routine to prevent muscle loss, reduce disability, and promote peripheral nerve reinnervation. Additionally, they should identify and avoid activities that trigger or worsen their symptoms, such as engaging in sports or wearing tight clothing, to prevent further nerve injury.

Nonpharmacological and noninvasive treatments should be recommended before considering medications. Patients with uncontrolled neuropathy are at a high risk of developing psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Pearls and Other Issues

Understanding and effectively managing genitofemoral neuralgia requires a comprehensive approach. Clinical pearls to aid healthcare professionals in diagnosing and treating this challenging condition, ensuring better patient outcomes and quality of life, include:

- Persistent groin pain after surgery lasting longer than 6 to 8 weeks should be considered as potentially neuropathic.

- Differentiating various neuralgias can be challenging due to overlapping cutaneous areas of distribution, which may complicate precise diagnosis.

- Specific nerve blocks can aid in accurately identifying the particular neuropathy.

- Failure of an adequately performed nerve block to control symptoms suggests that healthcare professionals should consider exploring alternative diagnoses.

- Healthcare professionals should utilize advanced diagnostic technologies, such as magnetic resonance neurography and 3-T magnetic resonance neurography-guided retroperitoneal genitofemoral nerve blocks, when available.

- Newer treatment modalities, including cryoablation, Botox injections, and implantable peripheral nerve stimulation, should be considered as appropriate.

- While surgery can be highly effective, with an overall reported cure rate of about 70%, other treatment options should generally be attempted first.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diagnosing genitofemoral neuralgia can be challenging due to the close anatomical relationship between the genitofemoral nerve and the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. Additionally, the known anatomical variability in cutaneous innervation by the cutaneous branches of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves complicates the diagnosis and relies heavily on a thorough dermatomal examination. Misdiagnosis can extend the disease course, delay appropriate treatment, and negatively affect the patient's lifestyle and potential for permanent disability. Therefore, physicians must become adept at recognizing the clinical signs, utilizing diagnostic tools, and applying available treatment modalities to manage genitofemoral neuralgia, thereby enhancing patient care and rehabilitation. Additionally, education on nerve anatomy, including nerve origin, course, innervation, and anatomical variability, must be thoroughly reinforced for surgeons operating within or around the nerve's path. This is crucial to prevent iatrogenic nerve injury that could lead to chronic neuralgic symptoms in patients.

A multidisciplinary team is essential for effective multimodal pain management, patient and family education, and minimizing both acute and long-term disability. Advanced care practitioners and nurses should excel in pain assessment, monitoring, patient education on pain management strategies, and postoperative care to prevent complications. Pharmacists must be skilled in managing and optimizing pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain, ensuring safe medication use, and minimizing adverse effects. Physical therapists must be well-versed in therapeutic exercises and modalities that alleviate pain and enhance functional mobility.

Regularly scheduled interdisciplinary case conferences enable team members to discuss complex cases, share insights, and update treatment plans. Standardized care pathways are established to treat patients with genitofemoral neuralgia, ensuring consistency in care delivery. By collaborating, interprofessional clinicians can enhance patient-centered care, improve clinical outcomes, ensure patient safety, and boost overall team performance in treating individuals affected by genitofemoral neuralgia.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cesmebasi A, Yadav A, Gielecki J, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Jan:28(1):128-35. doi: 10.1002/ca.22481. Epub 2014 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 25377757]

Rab M, Ebmer And J, Dellon AL. Anatomic variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve: implications for the treatment of groin pain. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2001 Nov:108(6):1618-23 [PubMed PMID: 11711938]

Murovic JA, Kim DH, Tiel RL, Kline DG. Surgical management of 10 genitofemoral neuralgias at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Neurosurgery. 2005 Feb:56(2):298-303; discussion 298-303 [PubMed PMID: 15670378]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMagee RK. Genitofemoral Causalgia : (A New Syndrome). Canadian Medical Association journal. 1942 Apr:46(4):326-9 [PubMed PMID: 20322413]

Thaler M, Manson TT, Holzapfel BM, Moskal J. Proximal femoral replacement using the direct anterior approach to the hip. Operative Orthopadie und Traumatologie. 2022 Jun:34(3):218-230. doi: 10.1007/s00064-022-00770-x. Epub 2022 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 35641789]

Schwarz GM, Hirtler L. The cremasteric reflex and its muscle - a paragon of ongoing scientific discussion: A systematic review. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2017 May:30(4):498-507. doi: 10.1002/ca.22875. Epub 2017 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 28295651]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAcar F, Ozdemir M, Bayrakli F, Cirak B, Coskun E, Burchiel K. Management of medically intractable genitofemoral and ilioingunal neuralgia. Turkish neurosurgery. 2013:23(6):753-7. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.7754-12.0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24310458]

Shanthanna H. Successful treatment of genitofemoral neuralgia using ultrasound guided injection: a case report and short review of literature. Case reports in anesthesiology. 2014:2014():371703. doi: 10.1155/2014/371703. Epub 2014 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 24804105]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGangopadhyay N, Pothula A, Yao A, Geraghty PJ, Mackinnon SE. Retroperitoneal Approach for Ilioinguinal, Iliohypogastric, and Genitofemoral Neurectomies in the Treatment of Refractory Groin Pain After Inguinal Hernia Repair. Annals of plastic surgery. 2020 Apr:84(4):431-435. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002226. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32000253]

Stark E, Oestreich K, Wendl K, Rumstadt B, Hagmüller E. Nerve irritation after laparoscopic hernia repair. Surgical endoscopy. 1999 Sep:13(9):878-81 [PubMed PMID: 10449843]

Chen DC, Hiatt JR, Amid PK. Operative management of refractory neuropathic inguinodynia by a laparoscopic retroperitoneal approach. JAMA surgery. 2013 Oct:148(10):962-7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3189. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23903521]

Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, Izard G, Kehlet H, Wijsmuller AR, Di Miceli D, Doglietto GB. International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2011 Jun:15(3):239-49. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0798-9. Epub 2011 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 21365287]

Elkins N, Hunt J, Scott KM. Neurogenic Pelvic Pain. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2017 Aug:28(3):551-569. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 28676364]

Poobalan AS, Bruce J, Smith WC, King PM, Krukowski ZH, Chambers WA. A review of chronic pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy. The Clinical journal of pain. 2003 Jan-Feb:19(1):48-54 [PubMed PMID: 12514456]

Lyon EK. Genitofemoral Causalgia. Canadian Medical Association journal. 1945 Sep:53(3):213-6 [PubMed PMID: 20323539]

O'Brien MD. Genitofemoral neuropathy. British medical journal. 1979 Apr 21:1(6170):1052 [PubMed PMID: 444919]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBohrer JC, Walters MD, Park A, Polston D, Barber MD. Pelvic nerve injury following gynecologic surgery: a prospective cohort study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Nov:201(5):531.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.023. Epub 2009 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 19761997]

Honig J. Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 Nov:100(5 Pt 1):1041-2; reply 1042 [PubMed PMID: 12423877]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCardosi RJ, Cox CS, Hoffman MS. Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 Aug:100(2):240-4 [PubMed PMID: 12151144]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTereshko Y, Enrico B, Christian L, Dal Bello S, Merlino G, Gigli GL, Valente M. Botulinum toxin type A for genitofemoral neuralgia: A case report. Frontiers in neurology. 2023:14():1228098. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1228098. Epub 2023 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 37465764]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVerstraelen H, De Zutter E, De Muynck M. Genitofemoral neuralgia: adding to the burden of chronic vulvar pain. Journal of pain research. 2015:8():845-9. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S93107. Epub 2015 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 26664155]

Giger U, Wente MN, Büchler MW, Krähenbühl S, Lerut J, Krähenbühl L. Endoscopic retroperitoneal neurectomy for chronic pain after groin surgery. The British journal of surgery. 2009 Sep:96(9):1076-81. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6623. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19672938]

Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet (London, England). 2006 May 13:367(9522):1618-25 [PubMed PMID: 16698416]

Parris D, Fischbein N, Mackey S, Carroll I. A novel CT-guided transpsoas approach to diagnostic genitofemoral nerve block and ablation. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2010 May:11(5):785-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00835.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20546515]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKu V, Cox C, Mikeska A, MacKay B. Magnetic Resonance Neurography for Evaluation of Peripheral Nerves. Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. 2021 Jan:16(1):e17-e23. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1729176. Epub 2021 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 34007307]

De la Fuente Hagopian A, Guadarrama-Sistos Vazquez S, Farhat S, Reddy NK, Trakhtenbroit MA, Echo A. The emerging role of MRI neurography in the diagnosis of chronic inguinal pain. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2023 Aug 18:408(1):319. doi: 10.1007/s00423-023-03050-9. Epub 2023 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 37594580]

Fritz J, Dellon AL, Williams EH, Rosson GD, Belzberg AJ, Eckhauser FE. Diagnostic Accuracy of Selective 3-T MR Neurography-guided Retroperitoneal Genitofemoral Nerve Blocks for the Diagnosis of Genitofemoral Neuralgia. Radiology. 2017 Oct:285(1):176-185. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161415. Epub 2017 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 28453433]

Macone A, Otis JAD. Neuropathic Pain. Seminars in neurology. 2018 Dec:38(6):644-653. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673679. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30522140]

Dimitrova A, Murchison C, Oken B. Acupuncture for the Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Mar:23(3):164-179. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0155. Epub 2017 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 28112552]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBah M, Abdulcadir J, Tataru C, Caillet M, Hatem-Gantzer G, Maraux B. Postoperative pain after clitoral reconstruction in women with female genital mutilation: An evaluation of practices. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction. 2021 Dec:50(10):102230. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102230. Epub 2021 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 34536588]

Kalso E. How strong is the evidence for the efficacies of different drug treatments for neuropathic pain? Nature clinical practice. Neurology. 2006 Apr:2(4):186-7 [PubMed PMID: 16932548]

Starling JR, Harms BA, Schroeder ME, Eichman PL. Diagnosis and treatment of genitofemoral and ilioinguinal entrapment neuralgia. Surgery. 1987 Oct:102(4):581-6 [PubMed PMID: 3660235]

Bates D, Schultheis BC, Hanes MC, Jolly SM, Chakravarthy KV, Deer TR, Levy RM, Hunter CW. A Comprehensive Algorithm for Management of Neuropathic Pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2019 Jun 1:20(Suppl 1):S2-S12. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz075. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31152178]

Fitridge R, Thompson M, Schug SA, Stannard KJD. Treatment of Neuropathic Pain. Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Reference Book for Vascular Specialists. 2011:(): [PubMed PMID: 30485013]

Yao C, Zhou X, Zhao B, Sun C, Poonit K, Yan H. Treatments of traumatic neuropathic pain: a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2017 Aug 22:8(34):57670-57679. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16917. Epub 2017 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 28915703]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRho RH, Lamer TJ, Fulmer JT. Treatment of genitofemoral neuralgia after laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy with fluoroscopically guided tack injection. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2001 Sep:2(3):230-3 [PubMed PMID: 15102257]

Heise CP, Starling JR. Mesh inguinodynia: a new clinical syndrome after inguinal herniorrhaphy? Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1998 Nov:187(5):514-8 [PubMed PMID: 9809568]

Verhagen T, Loos MJA, Scheltinga MRM, Roumen RMH. The GroinPain Trial: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Injection Therapy Versus Neurectomy for Postherniorraphy Inguinal Neuralgia. Annals of surgery. 2018 May:267(5):841-845. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28448383]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMatičič UB, Šumak R, Omejec G, Salapura V, Snoj Ž. Ultrasound-guided injections in pelvic entrapment neuropathies. Journal of ultrasonography. 2021 Jun 7:21(85):e139-e146. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2021.0023. Epub 2021 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 34258039]

Poh F, Xi Y, Rozen SM, Scott KM, Hlis R, Chhabra A. Role of MR Neurography in Groin and Genital Pain: Ilioinguinal, Iliohypogastric, and Genitofemoral Neuralgia. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2019 Mar:212(3):632-643. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.20316. Epub 2019 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 30620677]

Dalili D, Isaac A, Fritz J. Selective MR neurography-guided lumbosacral plexus perineural injections: techniques, targets, and territories. Skeletal radiology. 2023 Oct:52(10):1929-1947. doi: 10.1007/s00256-023-04384-7. Epub 2023 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 37495713]

Fritz J, Dellon AL, Williams EH, Belzberg AJ, Carrino JA. 3-Tesla High-Field Magnetic Resonance Neurography for Guiding Nerve Blocks and Its Role in Pain Management. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2015 Nov:23(4):533-45. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2015.05.010. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26499273]

Walter J, Reichart R, Vonderlind C, Kuhn SA, Kalff R. [Neuralgia of the genitofemoral nerve after hernioplasty. Therapy by peripheral nerve stimulation]. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen. 2009 Aug:80(8):741-4. doi: 10.1007/s00104-008-1624-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18830573]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDana E, Gupta H, Pathak R, Khan JS. Genitofemoral peripheral nerve stimulator implantation for refractory groin pain: a case report. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2023 Jan:70(1):163-168. doi: 10.1007/s12630-022-02348-4. Epub 2022 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 36369637]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOng Sio LC, Hom B, Garg S, Abd-Elsayed A. Mechanism of Action of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for Chronic Pain: A Narrative Review. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023 Feb 25:24(5):. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054540. Epub 2023 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 36901970]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZuckerman DA, Cooper JB, Sekhri NK, Bronstein M, Shnaydman I, Carr L, Siddiqui A, Pisapia JM. Intraoperative Nerve Stimulation as an Approach for the Surgical Treatment of Genitofemoral Neuralgia. The American journal of case reports. 2023 Aug 19:24():e940343. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.940343. Epub 2023 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 37596783]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCampos NA, Chiles JH, Plunkett AR. Ultrasound-guided cryoablation of genitofemoral nerve for chronic inguinal pain. Pain physician. 2009 Nov-Dec:12(6):997-1000 [PubMed PMID: 19935984]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFanelli RD, DiSiena MR, Lui FY, Gersin KS. Cryoanalgesic ablation for the treatment of chronic postherniorrhaphy neuropathic pain. Surgical endoscopy. 2003 Feb:17(2):196-200 [PubMed PMID: 12457217]

Starling JR, Harms BA. Diagnosis and treatment of genitofemoral and ilioinguinal neuralgia. World journal of surgery. 1989 Sep-Oct:13(5):586-91 [PubMed PMID: 2815802]

Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Kline DG. Surgical management of 33 ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Neurosurgery. 2005 May:56(5):1013-20; discussion 1013-20 [PubMed PMID: 15854249]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoseholm VB, Baker JJ, Rosenberg J. Nerve identification during open inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2023 Oct 24:408(1):417. doi: 10.1007/s00423-023-03154-2. Epub 2023 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 37874414]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKwee E, Langeveld M, Duraku LS, Hundepool CA, Zuidam M. Surgical Treatment of Neuropathic Chronic Postherniorrhaphy Inguinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 May 10:13(10):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13102812. Epub 2024 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 38792355]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlfieri S, Rotondi F, Di Giorgio A, Fumagalli U, Salzano A, Di Miceli D, Ridolfini MP, Sgagari A, Doglietto G, Groin Pain Trial Group. Influence of preservation versus division of ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genital nerves during open mesh herniorrhaphy: prospective multicentric study of chronic pain. Annals of surgery. 2006 Apr:243(4):553-8 [PubMed PMID: 16552209]

Jíšová B, Hladík P, East B. Triple neurectomy following Lichtenstein repair of inguinal hernia. Rozhledy v chirurgii : mesicnik Ceskoslovenske chirurgicke spolecnosti. 2023:102(9):363-365. doi: 10.33699/PIS.2023.102.9.363-365. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38286665]

Singh GP, Kuthiala G, Shrivastava A, Gupta D, Mehta R. The efficacy of ultrasound-guided triple nerve block (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) versus unilateral subarachnoid block for inguinal hernia surgery in adults: a randomized controlled trial. Anaesthesiology intensive therapy. 2023:55(5):342-348. doi: 10.5114/ait.2023.134277. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38282501]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFarrell SA, Clermont ME. Surgical treatment of intractable pelvic, groin, and perineal neuropathic pain in a gynaecologic patient: triple neurectomy. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2015 Feb:37(2):145-149. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30336-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25767947]

Beel E, Berrevoet F. Surgical treatment for chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair: a systematic literature review. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2022 Mar:407(2):541-548. doi: 10.1007/s00423-021-02311-9. Epub 2021 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 34471953]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmid PK, Chen DC. Surgical treatment of chronic groin and testicular pain after laparoscopic and open preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011 Oct:213(4):531-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.06.424. Epub 2011 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 21784668]

Nienhuijs S, Staal E, Strobbe L, Rosman C, Groenewoud H, Bleichrodt R. Chronic pain after mesh repair of inguinal hernia: a systematic review. American journal of surgery. 2007 Sep:194(3):394-400 [PubMed PMID: 17693290]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWong AK, Ng AT. Review of Ilioinguinal Nerve Blocks for Ilioinguinal Neuralgia Post Hernia Surgery. Current pain and headache reports. 2020 Dec 17:24(12):80. doi: 10.1007/s11916-020-00913-4. Epub 2020 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 33331965]

Benson JT, Griffis K. Pudendal neuralgia, a severe pain syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2005 May:192(5):1663-8 [PubMed PMID: 15902174]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBohrer JC, Chen CC, Walters MD. Pudendal neuropathy involving the perforating cutaneous nerve after cystocele repair with graft. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Aug:112(2 Pt 2):496-8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817f19b8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18669778]

Alevizon SJ, Finan MA. Sacrospinous colpopexy: management of postoperative pudendal nerve entrapment. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1996 Oct:88(4 Pt 2):713-5 [PubMed PMID: 8841264]

Robert R, Labat JJ, Bensignor M, Glemain P, Deschamps C, Raoul S, Hamel O. Decompression and transposition of the pudendal nerve in pudendal neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial and long-term evaluation. European urology. 2005 Mar:47(3):403-8 [PubMed PMID: 15716208]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchneiderman BI, Bomze E. Paresthesias of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve after pelvic surgery. The American surgeon. 1967 Jan:33(1):84-7 [PubMed PMID: 6016526]

Corona R, De Cicco C, Schonman R, Verguts J, Ussia A, Koninckx PR. Tension-free Vaginal Tapes and Pelvic Nerve Neuropathy. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2008 May-Jun:15(3):262-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.03.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18439494]

Irvin W, Andersen W, Taylor P, Rice L. Minimizing the risk of neurologic injury in gynecologic surgery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004 Feb:103(2):374-82 [PubMed PMID: 14754710]

Masarani M, Cox R. The aetiology, pathophysiology and management of chronic orchialgia. BJU international. 2003 Mar:91(5):435-7 [PubMed PMID: 12603394]

Kumar P, Mehta V, Nargund VH. Clinical management of chronic testicular pain. Urologia internationalis. 2010:84(2):125-31. doi: 10.1159/000277587. Epub 2010 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 20215814]

Chen DC, Amid PK. Persistent orchialgia after inguinal hernia repair: diagnosis, neuroanatomy, and surgical management: Invited comment to: Role of orchiectomy in severe testicular pain and inguinal hernia surgery: audit of Finnish patient insurance centre. Rönka K, Vironen J, Kokki H, Liukkonen T, Paajanen H. DOI 10.1007/s10029-013-1150-3. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2015 Feb:19(1):61-3. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1172-x. Epub 2013 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 24135814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmid PK, Hiatt JR. New understanding of the causes and surgical treatment of postherniorrhaphy inguinodynia and orchalgia. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007 Aug:205(2):381-5 [PubMed PMID: 17660088]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee SK, Wolfe SW. Peripheral nerve injury and repair. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000 Jul-Aug:8(4):243-52 [PubMed PMID: 10951113]

Moore AM, Bjurstrom MF, Hiatt JR, Amid PK, Chen DC. Efficacy of retroperitoneal triple neurectomy for refractory neuropathic inguinodynia. American journal of surgery. 2016 Dec:212(6):1126-1132. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.09.012. Epub 2016 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 27771034]