Introduction

The definition of the human abdomen is the anterior region of the trunk between the thoracic diaphragm superiorly and the pelvic brim inferiorly.

Understanding the anatomy of the abdomen will ultimately serve as one's cornerstone to understanding, diagnosing, and treating the pathology within.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The abdomen ultimately serves as a cavity to house vital organs of the digestive, urinary, endocrine, exocrine, circulatory, and parts of the reproductive system.

The anterior wall of the abdomen has nine layers. From outermost to innermost, they are skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, external obliques, internal obliques, transversus abdominis, transversalis fascia, preperitoneal adipose and areolar tissue, and the peritoneum. The peritoneum is one continuous membrane; however, it is classified as either visceral (lining the organs) or parietal (lining the cavity wall). A peritoneal cavity is therefore formed and filled with extracellular fluid used to lubricate the surfaces to reduce friction. The peritoneum is comprised of a layer of simple squamous epithelial cells.

The subcutaneous tissue of the anterior abdominal wall below the umbilicus also separates into two distinct layers: the superficial fatty layer known as Camper's fascia, and the deeper membranous layer known as Scarpa's fascia. This membranous layer is continuous with Colles fascia within the perineal region inferiorly.

The true abdominal cavity consists of the stomach, duodenum (first part), jejunum, ileum, liver, gallbladder, the tail of the pancreas, spleen, and the transverse colon.

The posterior wall of the abdominal cavity is known as the retroperitoneum.[2] The retroperitoneal structures include the suprarenal glands, aorta and inferior vena cava, duodenum (parts 2 to 4), pancreas (head and body), ureters, colon (descending and ascending), kidneys, esophagus (thoracic), and rectum.[3] One can use the mnemonic SAD PUCKER.

Embryology

The abdomen derives from three primary germ layers as an embryo. These are the ectoderm, which forms the epidermis, the somatic and splanchnic mesoderm, which forms the skeletal muscle of the abdominal wall and smooth muscle of the bowel, respectively, and the endoderm which forms the majority of the alimentary canal.

Embryologically, the gastrointestinal system develops as the foregut, midgut, and hindgut.

- Foregut: esophagus to the proximal duodenum where the bile duct enters

- Midgut: distal duodenum to proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon

- Hindgut: the distal third of the transverse colon to anal canal above the pectinate line

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The central abdominal wall is perfused by the superior epigastric artery (branch of the internal thoracic artery) above the umbilicus, and the inferior epigastric artery (branch of the external iliac artery) below the umbilicus. Venous drainage is accomplished via the internal and lateral thoracic veins superiorly, and the superficial epigastric (branch of the femoral vein) and inferior epigastric (branch of external iliac) veins inferiorly. Lymphatic drainage above the umbilicus is accomplished mainly via the axillary lymph nodes but does drain small amounts to the parasternal lymph nodes. Below the umbilicus, lymph drains to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Internally, the abdomen contains two major blood vessels - the aorta and the inferior vena cava. The aorta has three main branches that serve to supply the organs of the gastrointestinal tract, which includes the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries. These arteries branch off of the aorta anteriorly, while arteries that supply non-GI tract structures branch either laterally or posteriorly. Examples of such include the renal or gonadal arteries.

- The blood supply of the gastrointestinal tract follows the embryonic gut regions:

- The celiac artery supplies the foregut.

- The superior mesenteric artery supplies the midgut.

- The inferior mesenteric artery supplies the hindgut.

Note: The splenic flexure is known as a "watershed" area due to dual blood supply from distal artery branches, which can result in colonic ischemia.

Venous drainage from the organs of digestion occurs through the portal system, whereas non-digestion venous drainage occurs through the inferior vena cava and its tributaries.

The portal venous system consists of the superior mesenteric vein, inferior mesenteric vein (along with the superior rectal vein), and splenic vein and its tributaries, which all join to form the portal vein. The ligamentum teres, which contains the remnant of the umbilical vein, is of clinical significance due to its connection of the portal system to the abdominal wall. In the setting of portal hypertension, patients may experience dilation of the periumbilical veins, termed caput-medusae. Additionally, gastrointestinal cancers may metastasize to the anterior abdominal wall through the lymphatics that parallel the venous drainage, termed the Sister Mary Joseph sign/nodule.

Nerves

Important dermatomes include the xiphoid process at T6, the umbilicus at T10, and the umbilical fold at L1.

The skin and muscles of the abdominal wall receive their innervation by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-T11), the subcostal nerve (T12), the iliohypogastric nerve (L1, sensation to the suprapubic region), and the ilioinguinal nerve (L1, sensation to the ipsilateral medial thigh and scrotum).

Viscerally, the vagus nerve serves to parasympathetically innervate the vast majority of the gastrointestinal tract to include the foregut and midgut. The hindgut receives parasympathetic input from the sacral roots S2, S3, and S4.

- The foregut receives sympathetic innervation from the greater thoracic splanchnic nerve.

- The midgut receives sympathetic innervation from the lesser thoracic splanchnic nerve.

- The hindgut receives sympathetic innervation from the lumbar splanchnic nerves.

It is important to note that the visceral peritoneum and the underlying organs are insensitive to touch, temperature, or laceration, but rather perceive pain through stretch and chemical receptors. Due to the innervation of the organs, pain is poorly localized and refers to the dermatomes of the spinal ganglia that provide the sensory fibers. Consequently, foregut pain is usually referred to the epigastrium, midgut to the umbilicus, and hindgut to the pubic region.

Muscles

The abdominal muscles assist in the process of respiration, protect the inner organs, provide postural support, and serve to flex, extend, and rotate the trunk of the body.[4]

The four main abdominal muscle groups, from innermost to outermost, can be remembered by the mnemonic TIRE: Transversus abdominis, internal oblique, rectus abdominis, and external oblique.[5] The external and internal obliques run diagonally and perpendicular to each other. An easy way to remember which way the fibers run is to think of putting your hands in your pockets. The hand position represents the direction of the external obliques, and the internal obliques run perpendicular to this.

A midline raphe, the linea alba, is formed from the interweaving of the aponeuroses of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis.

The aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle splits to encapsulate the rectus abdominis muscles above the arcuate line, however, below the arcuate line, both the aponeurosis of the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis are anterior to the rectus abdominis.

Physiologic Variants

Various birth defects of the abdominal anatomy can occur. Examples include but are not limited to gastroschisis, omphalocele, congenital umbilical hernia, intestinal atresia, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, annular pancreas, Hirschsprung disease, malrotation, agenesis, etc.

Surgical Considerations

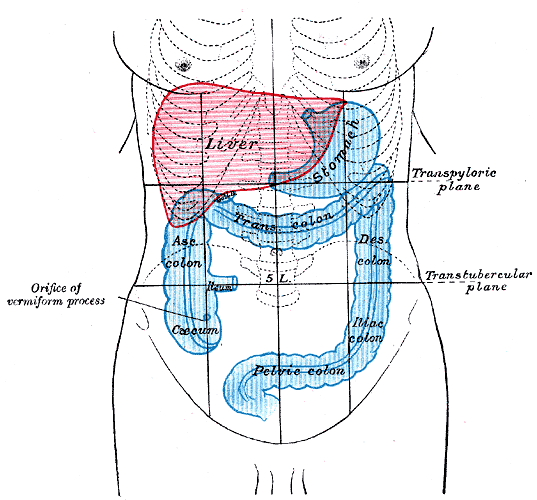

Clinically, the abdomen is roughly divided into nine regions by two sagittal planes from the midclavicular lines to the mid inguinal lines, and two transverse planes, one at the subcostal line and one at the iliac tubercles. The umbilicus serves at the center of the nine regions. Each region and its associated organs are detailed below:

- Right hypochondrium: liver, gallbladder

- Epigastrium: stomach, liver, pancreas, duodenum, adrenal glands

- Left hypochondrium: spleen, colon, pancreas

- Right lumber region: ascending colon, right kidney

- Umbilical region: navel, small intestine

- Left lumbar legion: descending colon, left kidney

- Right iliac fossa: appendix, cecum

- Hypogastric: Urinary bladder, sigmoid colon, female reproductive

- Left iliac fossa: descending colon, sigmoid colon

Surgically, the portal triad within the hepatoduodenal ligament is of considerable significance and includes the proper hepatic artery, common bile duct, and portal vein. The Pringle maneuver is when pressure is applied to this ligament to control hemorrhage.[6]

Clinical Significance

Abdominal signs and symptoms can be from a wide variety of disease processes to include vascular, infectious, trauma, autoimmune, musculoskeletal, idiopathic, neoplastic, congenital, etc. The details below are not meant to serve as an exhaustive list; however, it should serve as a guide for commonly encountered pathology within their respective quadrants and can help guide clinical decision making, especially with regards to imaging and surgery.[7][8][9][10]

Right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain

Commonly due to gastric reflux, gallbladder disease, hepatitis, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, kidney stone, retrocecal appendicitis, or bowel obstructions

Right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain

Commonly due to appendicitis, Crohn disease, cecal diverticulitis, ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, inguinal hernia, ischemic colitis, ovarian cyst, ovarian torsion, pelvic inflammatory disease, psoas abscess, testicular torsion, or kidney stones

Left upper quadrant (LUQ) pain

Commonly due to gastric reflux, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, splenic infarction or rupture, pyelonephritis, bowel obstruction, or aortic dissection

Left lower quadrant (LLQ) pain

Commonly due to diverticulitis, kidney stones, pyelonephritis, ectopic pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, inguinal hernia, ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion, pelvic inflammatory disease, psoas abscess, testicular torsion, abdominal aortic aneurysm, irritable bowel syndrome, or small bowel obstructions

Pectinate Line

The pectinate (dentate) line also serves as clinical significance. Above the pectinate line, one can expect internal hemorrhoids and adenocarcinoma. The internal hemorrhoids are not painful due to their visceral innervation. Below the pectinate line, one can expect external hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and squamous cell carcinoma. The external hemorrhoids are painful due to their somatic innervation.

Inguinal Hernias

A hernia, which is a protrusion of abdominal contents through an opening, can cause extreme pain, incarceration, and potential strangulation. Two types of inguinal hernias exist - direct and indirect. One can remember the anatomical difference through the mnemonic "MDs don't LIe." If the hernia is Medial to the epigastric blood vessels, then it is a Direct inguinal hernia. However, if the hernia is Lateral to the epigastric blood vessels, then it is an Indirect inguinal hernia.

Direct inguinal hernias, usually in older men, are only covered by external spermatic fascia and go through only the external inguinal ring.

Indirect inguinal hernias protrude through the internal and external inguinal rings and into the scrotum. They are covered by all three spermatic fascial layers: internal, cremasteric, and external.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brogi E, Kazan R, Cyr S, Giunta F, Hemmerling TM. Transversus abdominal plane block for postoperative analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2016 Oct:63(10):1184-1196. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0679-x. Epub 2016 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 27307177]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLambert G, Samra NS. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Retroperitoneum. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751047]

Selçuk İ, Ersak B, Tatar İ, Güngör T, Huri E. Basic clinical retroperitoneal anatomy for pelvic surgeons. Turkish journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Dec:15(4):259-269. doi: 10.4274/tjod.88614. Epub 2019 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30693143]

Tesh KM, Dunn JS, Evans JH. The abdominal muscles and vertebral stability. Spine. 1987 Jun:12(5):501-8 [PubMed PMID: 2957802]

Tsai HC, Yoshida T, Chuang TY, Yang SF, Chang CC, Yao HY, Tai YT, Lin JA, Chen KY. Transversus Abdominis Plane Block: An Updated Review of Anatomy and Techniques. BioMed research international. 2017:2017():8284363. doi: 10.1155/2017/8284363. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29226150]

Thomas JM, Van Fossen K. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Foramen of Winslow (Omental Foramen, Epiploic Foramen). StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489171]

Hodler J, Kubik-Huch RA, von Schulthess GK, Heiken JP, Katz DS, Menu Y. Emergency Radiology of the Abdomen and Pelvis: Imaging of the Non-traumatic and Traumatic Acute Abdomen. Diseases of the Abdomen and Pelvis 2018-2021: Diagnostic Imaging - IDKD Book. 2018:(): [PubMed PMID: 31314362]

Patterson JW, Kashyap S, Dominique E. Acute Abdomen. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083722]

Li PH, Tee YS, Fu CY, Liao CH, Wang SY, Hsu YP, Yeh CN, Wu EH. The Role of Noncontrast CT in the Evaluation of Surgical Abdomen Patients. The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):1015-1021 [PubMed PMID: 29981641]

Puylaert JB. Ultrasound of acute GI tract conditions. European radiology. 2001:11(10):1867-77 [PubMed PMID: 11702119]