Introduction

Lymphangiomas are uncommon, benign malformations of the lymphatic system that can occur anywhere on the skin and mucous membranes. Lymphangiomas can be categorized as deep or superficial based on the depth and size of the abnormal lymphatic vessels or as congenital or acquired.[1]

The deep forms of lymphangioma include two specific well defined congenital entities: cavernous lymphangiomas and cystic hygromas. [2] Superficial forms of lymphangioma include lymphangioma circumscriptum and acquired lymphangioma, which is also referred to in the literature as lymphangiectasia. Although both entities share similar clinical and histologic features, the term lymphangioma circumscriptum infers lymphatic channel dilation due to a congenital malformation of the lymphatic system. Whereas, the term lymphangiectasia, or acquired lymphangioma, denotes dilated lymphatic channels of previously normal lymphatics that have become obstructed by an external cause.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Congenital lymphangiomas form due to blockage of the lymphatic system during fetal development, though the cause remains unknown. Cystic lymphangiomas are associated with genetic disorders, including trisomies 13, 18, and 21, Noonan syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Down syndrome.[3] Acquired lymphangioma circumscriptum occurs in association with chronic lymphedema that leads to disruption of previously normal lymphatic channels.

Epidemiology

Lymphangiomas are rare in the United States. They represent 4% of all vascular tumors and approximately 25% of all benign pediatric vascular tumors. There is no racial or gender predilection. Lymphangiomas typically present at birth or in the first few years of life, while the acquired form of cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum often presents in adulthood.[4]

Pathophysiology

Lymphangiomas result from congenital or acquired abnormalities of the lymphatic system. The congenital form typically occurs before the age of 5 years and is due to improper connection of lymphatic channels to the main lymphatic drainage duct. Acquired lymphangiomas occur as a sequela of any interruption of previously normal lymphatic drainage such as surgery, trauma, malignancy, and radiation therapy.

Histopathology

On histopathologic examination, lesions of superficial lymphangioma consist of a collection of large lymphatic cisterns lying deep in the subcutaneous plane that communicate via dilated dermal lymphatic channels lined with endothelial cells. The overlying epidermis is usually acanthotic or hyperkeratotic and has an irregular elongation of rete pegs. No atypical vascular features, nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, or koilocytic changes typically exist. A mild to the moderate inflammatory infiltrate may be present.[5] Cystic or cavernous lymphangiomas demonstrate large, irregular vascular spaces lined with a single layer of flattened endothelial cells within a fibroblastic or collagenous stroma, which may contain lymphocytes. Penetration of muscle may be seen.

History and Physical

Clinically, lymphangioma circumscriptum appears as multiple, grouped or scattered, translucent or hemorrhagic vesicular papules that resemble frog-spawn. Because the lesions consist of a combination of blood and lymph elements, purple areas can be seen scattered within the vesicle-like papules. In the genital area, the surface can be verrucous, and the lesions may be mistaken for warts. The acquired form is most often found in the axilla, inguinal, and genital areas and there is often coexisting lymphedema. Associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, burning, lymphatic drainage, infection, and aesthetic concerns.

Cavernous lymphangioma typically presents during infancy as a painless, ill-defined subcutaneous swelling with no changes of the overlying skin that can be several centimeters in size. Rarely, an entire extremity may be affected. Patients may report tenderness upon deep palpation of the area. [6]They are commonly mistaken for cysts or lipomas in clinical practice.

Cystic hygromas are lymphatic malformations that are clinically more circumscribed than cavernous lymphangioma and typically occur on the neck, axilla, or groin. On physical examination, they are soft, with varying sizes and shapes, and will typically grow if not surgically excised. When posterior neck lesions are present, there may be an association with Turner syndrome, hydrops fetalis, or other congenital abnormalities. These lesions can be visualized in utero with the use of transabdominal or transvaginal sonography. MRI can be useful in determining the extent of anatomical involvement of cystic or cavernous lymphangiomas.

Evaluation

In most cases, a clinical diagnosis can be made based on the history and examination findings. As needed, dermoscopy and biopsy can be used to confirm the diagnosis and imaging may be warranted to assess the depth and extent of a lesion.

The dermoscopic examination can be helpful in distinguishing superficial lymphangioma from other cutaneous lesions. Two distinct dermoscopic patterns have been described: yellow lacunae surrounded by pale septa without the inclusion of blood and yellow to pink lacunae alternating with dark-red or bluish lacunae, representing the inclusion of blood. A more recently described dermoscopic finding is a “hypopyon-like” feature which consists of a color transition from dark to light in some lacunae. This occurs due to sedimentation of blood that separates cellular components to the bottom and serum to the upper part of the lacunae.[7]

Treatment / Management

Both superficial and deep lymphangiomas can be difficult to treat. When feasible the treatment of choice for any type of lymphangioma, however, remains surgical excision. Wide local excision of the affected lymphatic channels is necessary as recurrence is common. Recurrence rates for surgical excision of lymphangioma circumscriptum have been reported to be as high 23% in follow-up periods up to 81 months. Surgical success rates are higher for small, superficial lymphangiomas.[8](B2)

Destructive treatments with carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser, and electrosurgery have been reported to improve symptoms. Cryotherapy, superficial radiotherapy, and sclerotherapy with 23.4% hypertonic saline are less commonly used modalities. Direct injection of a sclerosing agent, including 1% or 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate, doxycycline or ethanol, can be made into lymphatic malformations. Compression may reduce swelling caused by lymphedema. Infection prevention is crucial.[9]

Differential Diagnosis

- Cutaneous melanoma

- Dabska tumour

- Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Dermatological manifestations of herpes simplex

- Cutaneous lipomas

- Dermatological manifestations of metastatic carcinomas

- Dermatological manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1

- Herpes zoster

- Lymphangiectasia

- Stewart-Treves syndrome

Pearls and Other Issues

The most common complications associated with lymphangioma circumscriptum include cellulitis and lymphatic fluid leakage. Rare cases of squamous cell carcinoma, verruciform xanthoma, and lymphangiosarcoma arising within lymphangioma have been reported. Large cystic hygromas of the neck can cause infection, as well more serious issues including dysphagia and respiratory problems.[10] [11]

Acquired lymphangiomas are not believed to have malignant potential; however, associated chronic lymphedema places the patient at risk for lymphangiosarcoma, which is an aggressive tumor with a dismal prognosis. Cutaneous angiosarcoma has also been reported in massive localized lymphedema in morbidly obese patients.

Acquired lymphangiectasia can be painful, and poor lymphatic drainage may lead to bacterial infection.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lymphangiomas are benign lesions that are difficult to diagnose and manage. These lesions are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a pediatrician, surgeon, dermatologist, and the primary care provider. While the treatment of choice is surgical excision, this is not always possible. Recurrence rates in excess of 30% have been reported. In addition, surgery can be associated with complications like lymphatic leaks, fistula formation and chronic wounds. These patients need a wound care nurse as the healing time is often many weeks or months. Parents should be educated about the treatment options because not all are effective or consistently effective.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

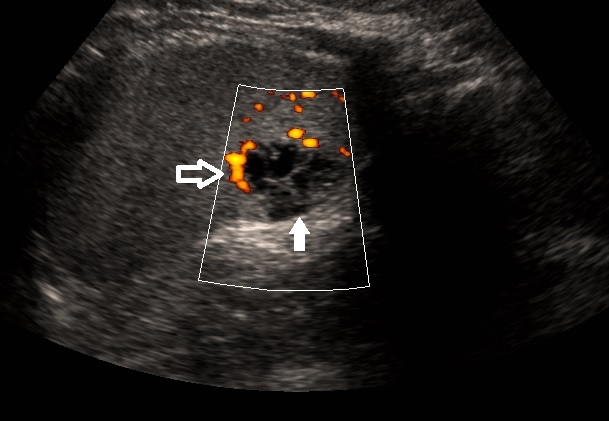

Ultrasound of the Spleen. Ultrasound of the spleen in sagittal plane demonstrates a multilocular cystic structure in the periphery of the spleen (solid white arrow). Power doppler shows flow along the wall of the cystic lesion (open white arrow). Findings are compatible with lymphangioma.

Contributed by W Coffey, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Stewart CJ, Chan T, Platten M. Acquired lymphangiectasia ('lymphangioma circumscriptum') of the vulva: a report of eight cases. Pathology. 2009:41(5):448-53. doi: 10.1080/00313020902885052. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19396719]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoia G, Maltese PE, Zampino G, D'Errico M, Cammalleri V, Convertini P, Marceddu G, Mueller M, Guerri G, Bertelli M. Cystic Hygroma: A Preliminary Genetic Study and a Short Review from the Literature. Lymphatic research and biology. 2019 Feb:17(1):30-39. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2017.0084. Epub 2018 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 30475086]

Sehgal VN, Sharma S, Chatterjee K, Khurana A, Malhotra S. Unilateral, Blaschkoid, Large Lymphangioma Circumscriptum: Micro- and Macrocystic Manifestations. Skinmed. 2018:16(6):411-413 [PubMed PMID: 30575511]

Ersoy AO,Oztas E,Saridogan E,Ozler S,Danisman N, An Unusual Origin of Fetal Lymphangioma Filling Right Axilla. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2016 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 27134953]

Hara H, Mihara M, Anan T, Fukumoto T, Narushima M, Iida T, Koshima I. Pathological Investigation of Acquired Lymphangiectasia Accompanied by Lower Limb Lymphedema: Lymphocyte Infiltration in the Dermis and Epidermis. Lymphatic research and biology. 2016 Sep:14(3):172-80. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2016.0016. Epub 2016 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 27599121]

Jiao-Ling L, Hai-Ying W, Wei Z, Jin-Rong L, Kun-Shan C, Qian F. Treatment and prognosis of fetal lymphangioma. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2018 Dec:231():274-279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.031. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30482553]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZaballos P, Del Pozo LJ, Argenziano G, Karaarslan IK, Landi C, Vera A, Llambrich A, Medina C, Bañuls J. Dermoscopy of lymphangioma circumscriptum: A morphological study of 45 cases. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2018 Aug:59(3):e189-e193. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12668. Epub 2017 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 28752523]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVignes S, Arrault M, Trévidic P. Surgical resection of vulva lymphoedema circumscriptum. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2010 Nov:63(11):1883-5. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.11.019. Epub 2009 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 20004630]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFarnoosh S, Don D, Koempel J, Panossian A, Anselmo D, Stanley P. Efficacy of doxycycline and sodium tetradecyl sulfate sclerotherapy in pediatric head and neck lymphatic malformations. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Jun:79(6):883-887. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.03.024. Epub 2015 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 25887132]

Wilson GR, Cox NH, McLean NR, Scott D. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within congenital lymphangioma circumscriptum. The British journal of dermatology. 1993 Sep:129(3):337-9 [PubMed PMID: 8286237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSims SM,McLean FW,Davis JD,Morgan LS,Wilkinson EJ, Vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a report of 3 cases, 2 associated with vulvar carcinoma and 1 with hidradenitis suppurativa. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2010 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 20592561]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence