Introduction

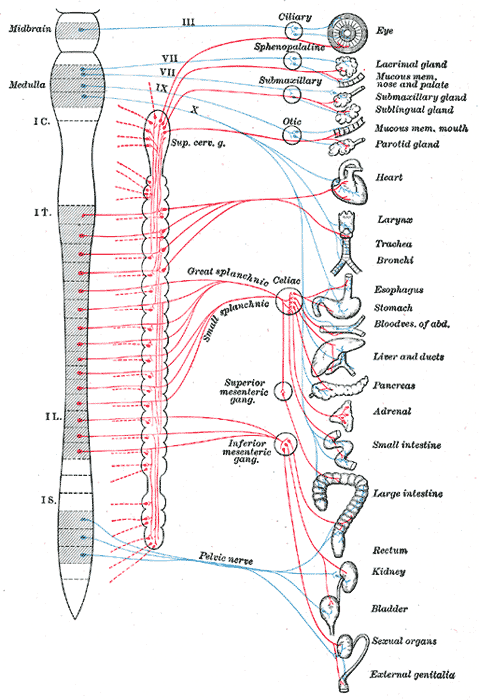

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is made up of pathways of neurons that control various organ systems inside the body, using many diverse chemicals and signals to maintain homeostasis. It divides into the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic component is better known as “fight or flight” and the parasympathetic component as “rest and digest.” It functions without conscious control throughout the lifespan of an organism to control cardiac muscle, smooth muscle, and exocrine and endocrine glands, which in turn regulate blood pressure, urination, bowel movements, and thermoregulation.[1]

Cellular Level

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Cellular Level

The autonomic nervous system is composed of many cells that perform a diverse set of functions. The sympathetic nervous system contains cell bodies that lie within the lateral gray column of the spinal cord running from T1 to L2. These neurons are known as preganglionic neurons and travel to ganglia, where they synapse and activate nicotinic receptors on postganglionic neurons using acetylcholine. The postganglionic neurons then travel to the target site and release norepinephrine to activate adrenergic receptors.

The parasympathetic nervous system is comprised of a cranial portion, consisting of cranial nerves III, VII, IX, and X and pelvic splanchnic nerves that exit from S2 to S4. The organization of the parasympathetic nerves is similar to the sympathetic nervous system, as preganglionic fibers synapse on postganglionic fibers, which then innervate target sites. A notable difference is that the preganglionic nerve fibers synapse on ganglia that are close to or embedded within their respective target sites, resulting in short postganglionic neurons.[2]

Development

Like many other areas of the nervous system, the autonomic nervous system forms through the migration of neural crest cells. Migration occurs primarily in dorsolateral and ventromedial directions. The ventromedial migration forms the cells that will become the ANS. Growth factors are involved in this process to orchestrate the migration and growth of axons, and current belief is that these factors stimulate the release of neurotransmitters, which then stimulates the release of more growth factors.[3]

Organ Systems Involved

The autonomic nervous system exerts influence over the organ systems of the body to upregulate and downregulate various functions. The two aspects of the ANS operate as opposing functions that act to achieve homeostasis. This next section will discuss this in terms of its divisions, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

The sympathetic nervous system, also known as the “fight or flight” system, increases energy expenditure and inhibits digestion. The following changes take place on activation of the sympathetic nervous system:

- Heart rate and cardiac muscle contractility increase

- The ciliary muscle relaxes, and the pupil becomes dilated for the betterment of far vision.

- Bronchodilation of the lungs

- Decreased GI motility

- Decreased urine output

- Relaxation of the detrusor muscle of the bladder and contraction of urethral sphincters

- Increased secretions from sweat glands

- Increased blood flow to muscles because of relaxation of arterioles

- Dilation of coronary arteries

- Constriction of large arteries and large veins

- Increased metabolism

- Increased glucose production and mobilization by the liver

- Increased lipolysis within fat tissue, ejaculation

- Suppression of the immune system

These changes function to increase movement and strength. Stressful situations that threaten survival, exercise, or the moments just before wakening are just a few examples of increases in sympathetic nervous system activity.[4]

The parasympathetic nervous system, also known as “rest and digest,” can be thought of as functioning in opposition to the sympathetic nervous system. Its functions include:

- A decrease in heart rate and contractility of cardiac muscle

- Constriction of the ciliary muscle and the pupil for near vision

- Increased secretion by lacrimal glands and salivary glands

- Increased gut motility, bronchoconstriction of the lungs

- Contraction of the detrusor muscle with the relaxation of urethral sphincters

- Glycogen synthesis by the liver

- Swelling of the clitoris and erection of the penis

- Activation of the immune system

The parasympathetic nervous system does not appear to exert much control over vascular tone as the sympathetic nervous system does.[2]

Mechanism

The ANS exerts its control through chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters. The neurotransmitters involved in the ANS are acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Preganglionic neurons of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions and postganglionic neurons of the parasympathetic nervous system utilize acetylcholine (ACh). Postganglionic neurons of the sympathetic nervous system use norepinephrine and epinephrine. Although, there are exceptions to this as described below.

ACh is released by all preganglionic neurons, regardless of their involvement in the parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system. ACh binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, a ligand-gated ion channel, on postganglionic neurons. Once ACh binds, the ion channel is open to allow the flow of ions, specifically sodium and calcium, which induces an excitatory postsynaptic potential, and results in the propagation of a neuronal signal down the axon.[5] ACh also gets released by postganglionic neurons of the parasympathetic nervous system. Here, ACh binds to muscarinic acetylcholine receptors on the target site, which are G-protein-coupled receptors. These act to perform the functions of the parasympathetic nervous system listed above. It is important to note that ACh also gets released by postganglionic neurons of sweat glands, and binds to and activates muscarinic receptors. This activity is an exception to the sympathetic nervous system, which normally involves norepinephrine as its chemical messenger released from postganglionic neurons.[6]

Norepinephrine gets released by postganglionic neurons of the sympathetic nervous system, which binds to and activates adrenergic receptors. These receptors further divide into alpha11 (G coupled receptor), alpha-2 (G coupled receptor), beta-1 (G coupled receptor), and beta-2 and beta-3 (G and G coupled receptor).

Epinephrine is released into systemic circulation by chromaffin cells within the adrenal gland, specifically the adrenal medulla. The sympathetic nervous system splanchnic nerves synapse on chromaffin cells and stimulate them to release epinephrine using the signal messenger acetylcholine. This feature of the adrenal gland is an important component of the sympathetic nervous system as it allows systemic effects to occur on major organ systems.[7]

Pathophysiology

The ANS is involved in several processes to maintain homeostasis. The symptoms and signs that are present due to a pathologic process involving the ANS depend on the area afflicted. For example, a tumor within the apex of the lung, known as a Pancoast tumor, can compress the sympathetic ganglia and cause Horner syndrome, resulting in ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis of the ipsilateral eye. Impairment of nerve fibers relaying autonomic signals, such as seen in diabetic autonomic neuropathy, can result in bowel dysmotility, resting tachycardia, orthostatic intolerance, constipation, fecal incontinence, and erectile dysfunction.

Clinical Significance

Of the diseases that afflict the ANS, orthostatic intolerance, neurogenic bowel, and erectile dysfunction are the important topics of the discussion below.

Orthostatic intolerance (OI) is a condition characterized by the onset of symptoms on standing that improve by lying down. An upright position is a stressor on the circulatory system that requires a healthy functioning heart, adequate blood volume, and functioning vascular tone to maintain appropriate blood pressures and cerebral blood flow. Without any one of these factors, symptoms of dizziness and loss of consciousness can occur on standing. The sympathetic nervous system exerts its influence to increase heart rate and cause vasoconstriction and venoconstriction. Without this feature of the sympathetic nervous system, OI will occur.[8]

Neurogenic bowel results from destruction or disease processes that damage nerves controlling bowel function and results in fecal incontinence or constipation. Parkinson disease, stroke, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injury are all causes of neurogenic bowel due to autonomic dysfunction.[9]

Erectile dysfunction (ED) can result from dysfunction in the parasympathetic nervous system. Parkinson disease, encephalitis, and stroke are known to be neurogenic causes of ED.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

McCorry LK. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. American journal of pharmaceutical education. 2007 Aug 15:71(4):78 [PubMed PMID: 17786266]

Gibbins I. Functional organization of autonomic neural pathways. Organogenesis. 2013 Jul-Sep:9(3):169-75. doi: 10.4161/org.25126. Epub 2013 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 23872517]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceErnsberger U, Rohrer H. Sympathetic tales: subdivisons of the autonomic nervous system and the impact of developmental studies. Neural development. 2018 Sep 13:13(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13064-018-0117-6. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30213267]

Biaggioni I. The Pharmacology of Autonomic Failure: From Hypotension to Hypertension. Pharmacological reviews. 2017 Jan:69(1):53-62. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.012161. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28011746]

Hamilton SL. The structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Progress in clinical and biological research. 1982:79():73-85 [PubMed PMID: 7045887]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeilbronn E, Bartfai T. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Progress in neurobiology. 1978:11(3-4):171-88 [PubMed PMID: 218252]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchmidt KT, Weinshenker D. Adrenaline rush: the role of adrenergic receptors in stimulant-induced behaviors. Molecular pharmacology. 2014 Apr:85(4):640-50. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.090118. Epub 2014 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 24499709]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStewart JM. Common syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. Pediatrics. 2013 May:131(5):968-80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2610. Epub 2013 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 23569093]

McClurg D, Norton C. What is the best way to manage neurogenic bowel dysfunction? BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2016 Jul 27:354():i3931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3931. Epub 2016 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 27815246]

Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2005 Nov:32(4):379-95, v [PubMed PMID: 16291031]