Introduction

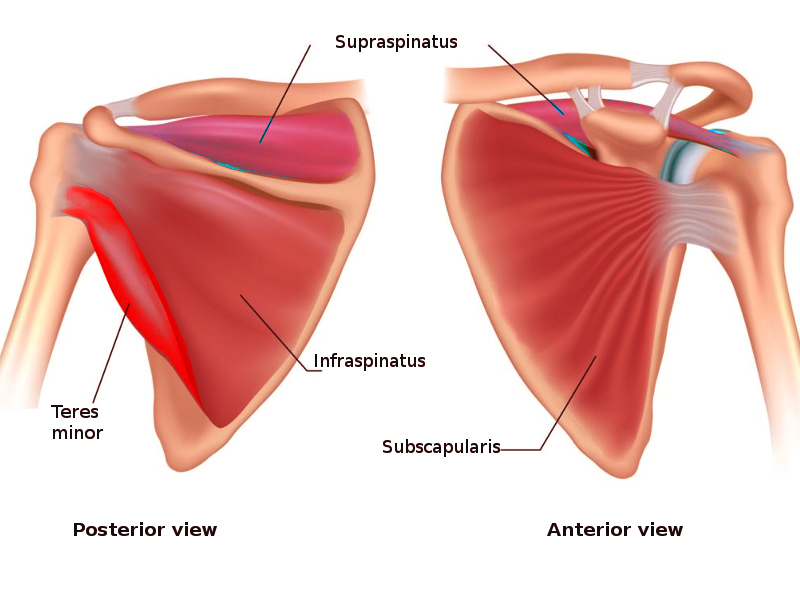

The shoulder joint classifies as a ball and socket joint; however, the joint sacrifices stability for mobility. The glenoid is a shallow rim, and one description is as looking like a golf ball on a tee or a basketball on a dinner plate. The rotator cuff consists of four muscles originating on the scapula and inserting on the superior humeral head to improve stability. The subscapularis inserts on the lesser tubercle of the humerus, and it functions as an internal rotator. The supraspinatus muscles insert onto the greater tubercle of the humerus with its function as an abductor for the initial 30 degrees of abduction. The infraspinatus also inserts onto the greater tubercle, but a little inferior to the supraspinatus, and it functions as an external rotator. The teres minor inserts inferior to the infraspinatus on the greater tuberosity, and it functions as an external rotator as well. Additionally, they all work as stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint.

Rotator cuff injury runs the full spectrum from injury to tendinopathy to partial tears, and finally complete tears. Age plays a significant role. Injuries ranged from 9.7% in those 20 years and younger increasing to 62% in patients 80 years and older (whether or not symptoms were present).[1] Increasing age and those with unilateral pain are also at risk for a tear in the rotator cuff of the opposite shoulder. In a study comparing patients with unilateral shoulder pain, the average age for a patient having no cuff tear was 48.7 years. After age 66, there is a 50% likelihood of bilateral tears. Additionally, age was linked to the presence and type of tear but did not correlate with tear size.[1]

Unfortunately, there is a lack of good evidence on the optimal treatment of tears in patients younger than 40.[2] The tears tend to be more traumatic and likely respond to surgery better, but the role of non-surgical management needs to be better defined.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Age is the most common factor for rotator cuff disease. It is a degenerative process that is progressive.[3] Smoking is a known risk factor. A systematic review demonstrated increased rates and sizes of degenerative tears along with symptomatic tears seen in smokers; this has the potential to increase the number of surgeries.[4] Another risk factor is family history. In a study of rotator cuff disease in those under 40 years of age, there was a significant correlation between individuals with RC disease up to third cousins. [4] Interestingly, poor posture has also been shown to be a predictor of rotator cuff disease. Tears were present in 65.8% of patients with kyphotic-lordotic postures, 54.3% with flat-back postures, and 48.9% with sway-back postures; tears were present in only 2.9% of patients with ideal alignment.[4] Other risk factors include trauma, hypercholesterolemia, and occupations or activities requiring significant overhead activity.[4][5]

Partial tears are at risk for further propagation. These risk factors include: tear size, symptoms, location, and age. Tear size: A small tear may remain dormant, while larger tears are more likely to undergo structural deterioration. The critical size for sending a small tear towards a larger or complete tear has yet to be defined.[6] Tear propagation correlates with symptom development. Actively enlarging tears have a five times higher likelihood of developing symptoms than those tears that remain the same size.[6] The location of the tear also influences progression. Anterior tears are more likely to progress to cuff degeneration.[6] Finally, age is a risk factor. Patients over age 60 are more likely to develop tears that progress. Younger patients with full-thickness tears appear more capable of adapting to stress and tear propagation than those 60 years of age and older.[6]

Epidemiology

In adults, rotator cuff injury is the most common tendon injury seen and treated. Statistically, approximately 30% of adults age over 60 have a tear, and 62% of adults over 80 have tears.[3] In Germany, a prospective study on 411 asymptomatic shoulders demonstrated a 23% overall prevalence of RC tears with 31% in those of age 70 and 51% in those 80 years of age. [7] Other studies from Europe gave slightly lower results. One study from Austria on 212 asymptomatic shoulders demonstrated only a 6% prevalence of full-thickness tears.[8] A Norwegian study on 420 asymptomatic volunteers ages 50 to 79 revealed FTT in 32 subjects (7.6%).[9]

Pathophysiology

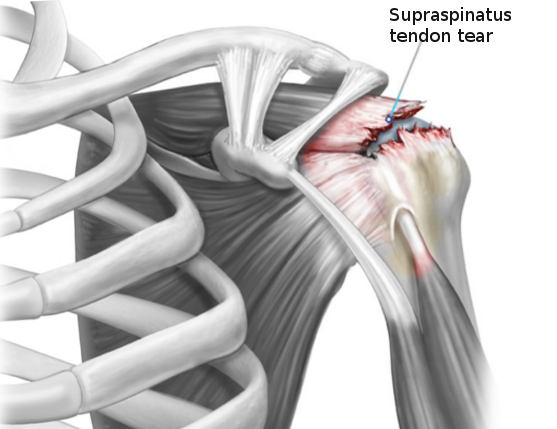

Rotator cuff injury starts from trauma. Macro-trauma causes an acute tear, which is seen generally in a younger patient resulting in a complete tear. Micro-trauma causes tendon degeneration and with insufficient healing, leads to degenerative tears. Typically, acute tears happen in younger patients, and degenerative tears occur in older patients. However, a smaller amount of force is needed to cause a complete tear if there is sufficient tendon degeneration.

History and Physical

The history of rotator cuff disease all starts with pain. The pain can be acute and arise from a traumatic event, or it can be gradual and mild, but steadily increasing. Generally, active individuals will present when they can no longer do their sport, activity, or job without causing pain. Often they will try to adapt or alter their biomechanics to remain active. Only when they can no longer adapt will they present. For instance, a baseball pitcher will begin to move their motion from an overhead movement to more of a sidearm throw to try and maintain velocity. Once the pain continues or the velocity drops sufficiently, will they seek care. Depending on when the patient presents, the tendon will be anywhere from tendinopathy to partial tear to complete tear.

Additionally, patients will report increasing pain and difficulty with overhead activity, activities of daily living. They may also report pain when lifting or carrying heavy objects. The pain can occasionally radiate down into the area of the deltoid muscle. Quite often, they will report pain when lying on their side to sleep. In younger patients, overuse tendinopathy is the cause, and older patients often have osteoarthritis as a contributing factor.

On physical exam, tenderness along at the insertion of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles in the greater/lesser tuberosity can be present. Upon inspection, muscle atrophy may be visible in the supraspinatus or infraspinatus fossa of the scapula.[10] Additionally, checking the cervical range of motion and performing a Spurling test can help look for cervical disc disease as a source of the pain. The next step is to have the patient demonstrate the range of motion in both abduction and flexion. Rotator cuff pathology will cause pain in the range of motion; this is commonly called a painful arc. It is also helpful to observe the scapulothoracic motion. The longer the pain has been present, the more likely patients will develop scapular dyskinesis. Normally, the scapula does not begin to abduct until the arm abducts to 90 degrees. When dyskinesis is present, scapular motion initiates well before the arm reaches 90 degrees of abduction.

There is limited evidence for any of the tests commonly used in diagnosing rotator cuff disease as being very sensitive or specific.[11] The Jobe or empty can test used to evaluate for supraspinatus tendinopathy. The patient elevates the arm to about 90 degrees, and with the thumb down (having an empty can in the patient's hand), isometric force is applied downward. The full can test is a variation where the thumb is up (having a full can in the patient's hand). These tests have high sensitivity but are unfortunately not specific.[4] Next, resisted external rotation is used to evaluate for infraspinatus/teres minor muscle pathology. The patient adducts their arms to their side, and the patient isometrically resists an internal rotation force. For the subscapularis, the belly press is useful for evaluation. The patient places their hand on their abdomen and then resists the examiner's attempt to push the elbow forward off the abdominal wall. Pain or weakness with any of these motions is considered positive tests. If pain limits the exam, a diagnostic subacromial injection can be done to see if reducing the patient's pain improves the exam. Placing an anesthetic agent (lidocaine is the most common choice) in the subacromial space can improve the specificities of these tests.[4]

When considering a rotator cuff tear, there are variations in the tests noted above. If the patient cannot hold the empty can test position, it is called a drop arm test. Next is the external rotation lag sign. With the patient in external rotation, the arm is fully externally rotated. If the patient cannot maintain this position, there is a good chance they have a ruptured supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus muscle.[12] Finally, the inability to keep the hand on the abdominal wall with the belly press test suggests there is a chance the patient has ruptured their subscapularis muscle.

Evaluation

When it comes to shoulder imaging, there are three options: plain radiography, ultrasound, and MRI/MR arthrography. For rotator cuff disease, MR arthrography does not add any additional benefits over an MRI. It is more expensive and requires an intra-articular injection of gadolinium.

Imaging begins with X-rays, and the standard is four views AP, true AP (Grashey view), scapular Y (lateral), and axillary views. The Grashey view activates the deltoid muscle, thus allowing proximal humeral migration. In patients with a chronic, large tear, the proximal humerus will migrate superior. The scapular Y view evaluates for acromial spurs often associated with cuff tears. Finally, the axillary view will show joint space narrowing along with anterior or posterior humeral subluxation.[10]

Ultrasound has become an excellent tool for evaluating the rotator cuff. It is less expensive and has the capability of assessing dynamic movements of the shoulder. A 2013 review article compared MRI, MR arthrography, and ultrasound to diagnose rotator cuff tears. The gold standard was open or arthroscopic surgery gold standard. With partial-thickness tears, both MRI and ultrasound performed well. All three imaging modalities were able to rule in or rule out a full-thickness. For both partial- and full-thickness tears, no significant differences were shown in the imaging modalities' abilities to demonstrate a tear.[12] Ultrasound has limitations due to the skill required to obtain appropriate images, and it can be difficult to distinguish between chronic tears and tendinopathies.

MRI remains the gold standard in the US. The images are utilized in pre-procedure planning and can show tear size, location, retraction, muscle atrophy, chronic changes in the tendon and muscle associated with degenerative changes, and other associated pathology.[10][4] All these factors will go into planning a potential surgical procedure.

Treatment / Management

The treatment depends on the age of the patient, their functional demands, and the acuteness vs. chronicity of the tear. For complete tears in patients under 40, surgical treatment is the generally recommended treatment followed by appropriate rehabilitation. These are usually traumatic injuries and respond well to surgery. However, the data is limited and based mostly on studies in older patients.[2]

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons developed some recommendations. They determined high-level evidence of surgical treatment for full-thickness tears was weak.[13] In the same article, the group determined there were appropriate use criteria based on available data and expert opinion. The authors reviewed five classes of treatment. First, non-surgical management is always appropriate, providing they are responding with improved function and decreased pain. Second, repairs can be appropriate even if the patient responds to non-surgical care. Third, for those healthy patients who remain symptomatic, then repair is the appropriate treatment. Fourth, for cases of chronic, massive tears, debridement/partial repair and/or reconstruction may be indicated. Finally, for those with painful pseudoparalysis with an irreparable tear, arthroplasty may be appropriate.[13]

For patients who do respond to non-surgical care, will do so in 6 to 12 weeks.[13]

Any patient with asymptomatic tears should have nonoperative management. Newly diagnosed, symptomatic rotator cuff tears may start with physical therapy addressing both core and scapular muscle strengthening. This approach is associated with similar clinical outcomes when compared to surgical repair for both small and medium-sized tears. Additionally, therapy was is an effective primary treatment modality in most patients, even with full-thickness rotator cuff tears followed over two years. Oddly enough, in this study group, low expectations regarding the efficacy of rehabilitation are the strongest predictor of patients who would eventually go to surgery.[3]Quite often subacromial injections with corticosteroids are frequently employed setting of rotator cuff tears. However, there is little reproducible evidence to support their effectiveness and improve long-term clinical outcomes when used alone.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

- SLAP or other labral tears

- Subacromial impingement from bursitis, os acromiale, bone spurs

- Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis

- Biceps tendinitis

- Calcific tendinitis

- Cervical radiculopathy

Prognosis

A recent meta-analysis published in 2019 out of the United Kingdom evaluating the treatment outcomes (patient-reported outcomes) demonstrated both surgical and non-surgical treatment groups had the largest improvement at 12 months. Then improvements leveled out. There was no clear advantage of surgery over non-surgical treatments.[14]

An algorithm was developed to help guide patient selection where tears categorize into three groups. [10] Group 1: early operative repair. One indication would be patients with an acute event and imaging corroborating the history. Especially with a subscapularis tear with or without biceps tendon instability. In those patients with pain and weakness before the injury would likely be an acute on chronic tear scenario and early intervention can be considered when imaging shows minimal muscle atrophy or degenerative changes should undergo early surgical interventions. Patients younger than 62 to 65 with small and medium-sized tears with minimal to no atrophy on imaging would be another group to consider early operative management. Group 2: In patients with painful partial or full-thickness tears who do not have an acute onset of pain, even if tendons are potentially repairable, they should undergo non-surgical treatment initially. In these cases, rehabilitation has shown consistent benefit in improving function and outcomes. Group 3: should undergo maximal non-surgical treatment. This group would be those who are tendons are unlikely to heal. Included in this group are those over 70 years old, those with chronic full-thickness tears with significant tendon retraction, advanced degenerative changes in the muscles, any signs of proximal humeral migration.

Complications

The most likely complication would be retearing of the cuff repair — this is minimizable with proper patient selection. Postoperative complications, in addition to those generally seen, would be adhesive capsulitis, inability to regain motion, or cuff strength.

Deterrence and Patient Education

No studies examine prevention strategies. Theoretically, proper cuff function can help decrease the risk of degenerative tears. In an observational study, rotator cuff tears were seen more predominately in those with specific postures. Also, another study looking at radiographically measured subacromial space found reduced acromiohumeral space correlated with hyperkyphotic posture.[4]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Rotator cuff disease is among the most common tendon injuries seen and generally affects the older population. These patients tend to have more chronic conditions and take more medications. Most patients will do well with conservative measures, but open communication with their primary care physician, physical therapist, and sports medicine physician will optimize outcomes.

When the decision is made to proceed to surgery, patients may need clearance to undergo anesthesia; this occasionally requires permission from their primary care doctor or other specialists like cardiology, pulmonary, nephrology if they have renal failure or are undergoing dialysis. The team will need to address any chronic metabolic conditions and should look to optimize blood glucose levels, A1C, as well as optimizing any blood coagulation.

After the surgical procedure, clear communication between the operative and post-operative teams of physicians and nurses (including nurses with specialty training in orthopedics) to ensure the continued safety of the patient as they recover is critical. Discussions about medications and medical conditions should be open and frank, so the entire team ensures an appropriate handoff. The nursing staff should perform post-operative monitoring, assist with patient and family education, and coordinate appropriate follow-up.

As the patient proceeds with recovery and goes through the (typically long) rehabilitation process, open communication between the surgeon and physical therapist will optimize the patient's recovery. Physical therapists also often have involvement in conservatively managed cases or instances attempting conservative management in an attempt to preclude surgery. The therapist must report back to the treating clinician with their findings regarding progress or lack thereof.

Managing rotator cuff tears requires an interprofessional team approach, including the clinicians, specialists, orthopedic and surgical nurses, and physical therapists.

Media

References

Codding JL, Keener JD. Natural History of Degenerative Rotator Cuff Tears. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2018 Mar:11(1):77-85. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9461-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29411321]

Lazarides AL, Alentorn-Geli E, Choi JH, Stuart JJ, Lo IK, Garrigues GE, Taylor DC. Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a different disease than rotator cuff tears in elderly patients. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2015 Nov:24(11):1834-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.031. Epub 2015 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 26209913]

Dang A, Davies M. Rotator Cuff Disease: Treatment Options and Considerations. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2018 Sep:26(3):129-133. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000207. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30059447]

Sambandam SN, Khanna V, Gul A, Mounasamy V. Rotator cuff tears: An evidence based approach. World journal of orthopedics. 2015 Dec 18:6(11):902-18. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i11.902. Epub 2015 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 26716086]

Moulton SG, Greenspoon JA, Millett PJ, Petri M. Risk Factors, Pathobiomechanics and Physical Examination of Rotator Cuff Tears. The open orthopaedics journal. 2016:10():277-285 [PubMed PMID: 27708731]

Schmidt CC, Morrey BF. Management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: appropriate use criteria. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2015 Dec:24(12):1860-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.042. Epub 2015 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 26208976]

Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil R. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 1999 Jul-Aug:8(4):296-9 [PubMed PMID: 10471998]

Fehringer EV, Sun J, VanOeveren LS, Keller BK, Matsen FA 3rd. Full-thickness rotator cuff tear prevalence and correlation with function and co-morbidities in patients sixty-five years and older. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2008 Nov-Dec:17(6):881-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.05.039. Epub 2008 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 18774738]

Schibany N, Zehetgruber H, Kainberger F, Wurnig C, Ba-Ssalamah A, Herneth AM, Lang T, Gruber D, Breitenseher MJ. Rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic individuals: a clinical and ultrasonographic screening study. European journal of radiology. 2004 Sep:51(3):263-8 [PubMed PMID: 15294335]

Hsu J, Keener JD. Natural History of Rotator Cuff Disease and Implications on Management. Operative techniques in orthopaedics. 2015 Mar 1:25(1):2-9 [PubMed PMID: 26726288]

Hegedus EJ,Goode AP,Cook CE,Michener L,Myer CA,Myer DM,Wright AA, Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. British journal of sports medicine. 2012 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 22773322]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceO'Kane JW, Toresdahl BG. The evidenced-based shoulder evaluation. Current sports medicine reports. 2014 Sep-Oct:13(5):307-13. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000090. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25211618]

Schmidt CC, Jarrett CD, Brown BT. Management of rotator cuff tears. The Journal of hand surgery. 2015 Feb:40(2):399-408. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.06.122. Epub 2015 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 25557775]

Khatri C, Ahmed I, Parsons H, Smith NA, Lawrence TM, Modi CS, Drew SJ, Bhabra G, Parsons NR, Underwood M, Metcalfe AJ. The Natural History of Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears in Randomized Controlled Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2019 Jun:47(7):1734-1743. doi: 10.1177/0363546518780694. Epub 2018 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 29963905]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence