Introduction

A hydatidiform mole, commonly referred to as a molar pregnancy, is a rare abnormality in pregnancy classified under gestational trophoblastic diseases (GTD), which stem from the placenta and may metastasize.[1] Hydatidiform moles are characterized by abnormal fertilization, resulting in villous hydrops and trophoblastic hyperplasia with or without embryonic development.[1] Other forms of GTD include gestational choriocarcinoma—which can be aggressively malignant and invasive—and placental site trophoblastic tumors. Please see StatPearls' companion reference, "Gestational Trophoblastic Disease," for more information. Although described as early as Hippocrates’ era, who explained their formation through the consumption of dirty water by pregnant women, the condition was more accurately characterized in 1752 by William Smelie, who likened its appearance to a “bunch of grapes,” a hallmark feature of molar pregnancies resulting from swollen, hydropic villi.[2][3][4]

Hydatidiform moles are categorized as complete or partial and are usually noninvasive forms of GTD. Overrepresentation of the paternal genome in sporadic hydatidiform moles is a fundamental genetic event leading to overall alteration of imprinting gene expression in the molar trophoblast, being completely androgenetic in complete hydatidiform moles and diandric triploid in partial hydatidiform moles.[5] However, although hydatidiform moles are considered benign, they are premalignant lesions and can potentially become malignant and invasive.[1]

Complete molar pregnancies present with symptoms such as first-trimester vaginal bleeding, severe nausea, and high β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels. Partial moles may present similarly but often resemble a spontaneous abortion and may include detectable fetal heart tones. Both molar types are detectable via ultrasonography, which typically reveals distinct patterns; complete moles demonstrate anechoic cystic clusters (“grape clusters”) and partial moles demonstrate fetal parts.

Histopathological examination postevacuation confirms the diagnosis with visualization of characteristic villous changes. Treatment typically involves dilation and curettage (D&C), and hysterectomy may be considered for patients not desiring future pregnancies. Posttreatment, regular β-hCG monitoring is essential to detect potential progression to gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hydatidiform moles originate from aberrantly proliferated placental tissue.[2] A complete mole results from the fertilization of an empty ovum by 1 or 2 sperms, resulting in paternally-derived haploid genetic material.[5] Therefore, a complete mole comprises solely maternally derived mitochondrial DNA, while all its nuclear DNA originates paternally.[1] The haploid paternal genetic material undergoes duplication, resulting in a diploid 46,XX or 46,XY molar pregnancy; 46,XX is the more common karyotype.[6]

Conversely, a partial mole arises when a viable ovum is fertilized by 2 or more sperms, with resultant karyotype 69,XXY.[5] Partial molar pregnancies, therefore, feature a triploid diandrous monogynic genome, typically resulting from the fertilization of an ovum by 2 or more sperms or rarely from reduplications of a single sperm’s genetic material post-fertilization, resulting in a triploid 69,XXY; 69,XXX; or 69,XYY karyotypes.[1]

Epidemiology

A full epidemiological understanding of hydatidiform moles necessitates further research; data indicate a higher incidence in Southeast Asia.[5] This increased incidence in Asia compared to other geographical regions may be attributed to genetic differences within ethnic groups.[1] Geographical correlation suggests an increased incidence of molar pregnancies at the extremes of maternal age, including patients with advancing maternal age (older than 35 years) and among adolescent pregnancies.[1] The risk significantly escalates with age, increasing 5-fold in women older than 40 and 2.5-fold in those older than 35.[7] Additionally, hydatidiform moles are more likely to occur in patients with a history of this condition.[1]

Pathophysiology

Based on histopathological examination and genetics, hydatidiform moles can be classified as complete or partial hydatidiform moles.[8] The common pathology of these lesions is excessive proliferation of trophoblast and placental villi becoming edematous, forming hydatidiform structures.[9] In complete moles, hydrops is fully developed, and most villi are involved.[10] In partial moles, by contrast, hydrops remains characteristically focal.[11] Fetal parts are absent in complete moles, whereas partial moles show evidence of fetal development, such as amnion vessels with fetal red blood cells.[12][9] Molar pregnancies are genetically characterized with 2 copies of the paternal genome. Complete moles are diploid and androgenetic, with both sets of chromosomes derived from the paternal genome and no maternal contribution to the nuclear genome.[8] The monospermic 46, XX karyotype is most common, resulting from the fertilization of an ovum by a single sperm that then duplicates its DNA.[8][13]

About 10% of complete hydatidiform moles are 46, XY, arising from fertilization of an empty ovum by 2 sperms, known as dispermy. 46,YY embryos are presumed to be nonviable.[8] Partial moles are almost always triploid, having an additional paternal set of chromosomes. Most have a 69,XXX or 69,XXY karyotype usually resulting from fertilization of an ovum by 2 sperms, or less frequently, a diploid sperm.[9] Trisomy with XYY karyotype is rarely seen, and YYY karyotype has not been observed.[9] Most molar pregnancies are sporadic. A small subset of women has an inherited predisposition to recurrent molar pregnancies, referred to as familiar recurrent hydatidiform mole.[8]

Histopathology

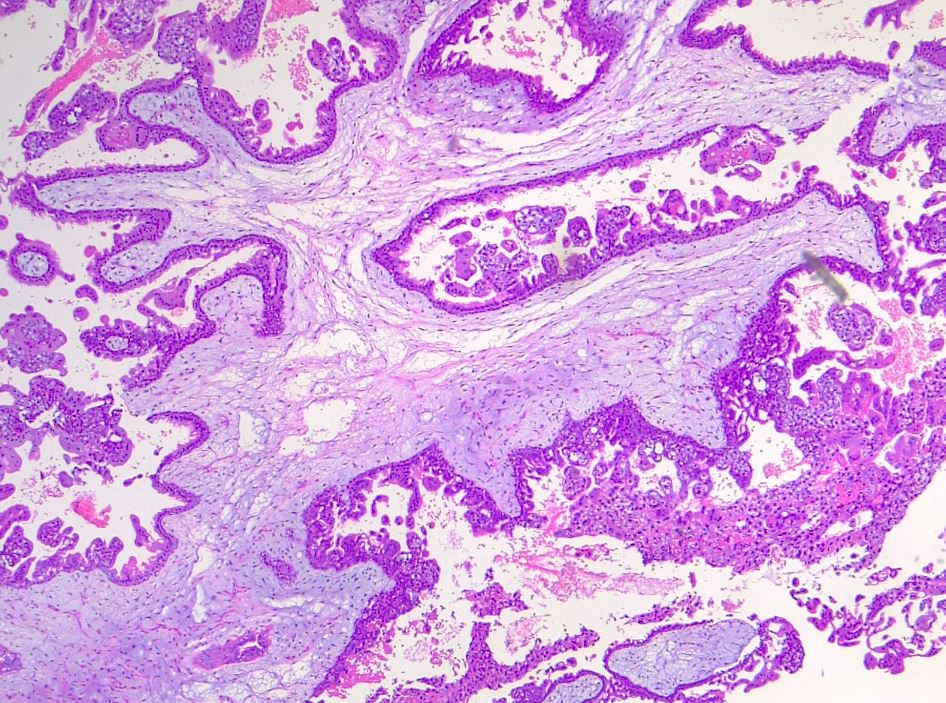

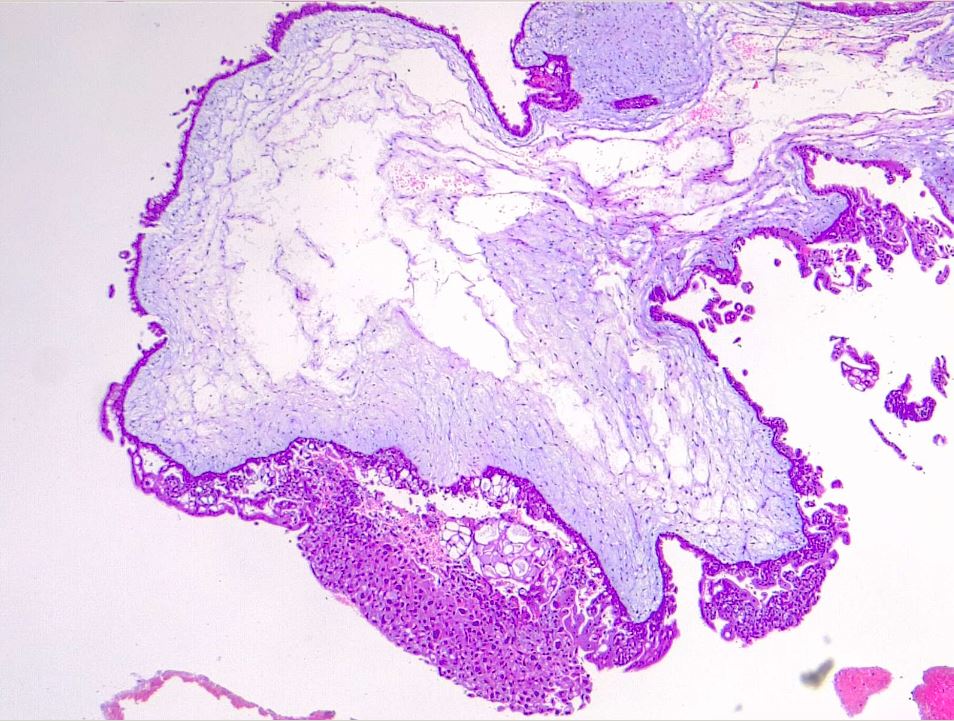

Histologically, both complete and partial hydatidiform moles are characterized by an overgrown villous trophoblast with cystic "swollen" villi.[1] In the second trimester, this can be macroscopically visualized as clusters of vesicles developed from the transformation of chorionic villi.[1] An important distinguishing feature between complete and partial moles is a complete lack of embryonic or fetal tissue in complete moles, in contrast to embryonic tissue in partial moles.[1]

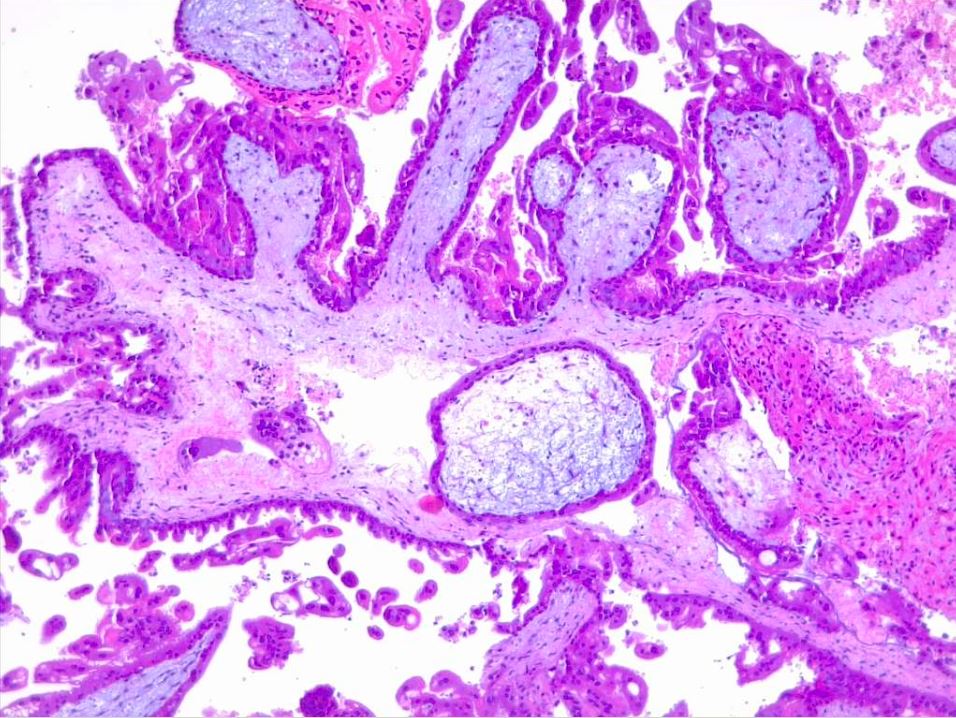

Microscopic examination of complete moles reveals poorly vascularized chorionic villi with hydropic swelling and myxomatous, edematous stroma, creating a florid cistern filled with stromal fluid (see Images. Hydatiform Mole and Dysmorphic Villi in Hydatiform Mole).[1] The absence of embryonic tissue results from early tissue death before a functioning circulation system is established.[14] Increased trophoblastic proliferation is linked to elevated endothelial growth factor receptor expression in trophoblastic cells (see Image. Hydropic Villi and Trophoblastic Proliferation). The absence of p57 expression due to the androgenic origin of complete moles explains the increased trophoblastic and stromal proliferation and invasive potential. Compared to partial moles, complete moles have a higher risk of developing both an invasive mole and choriocarcinoma.[1]

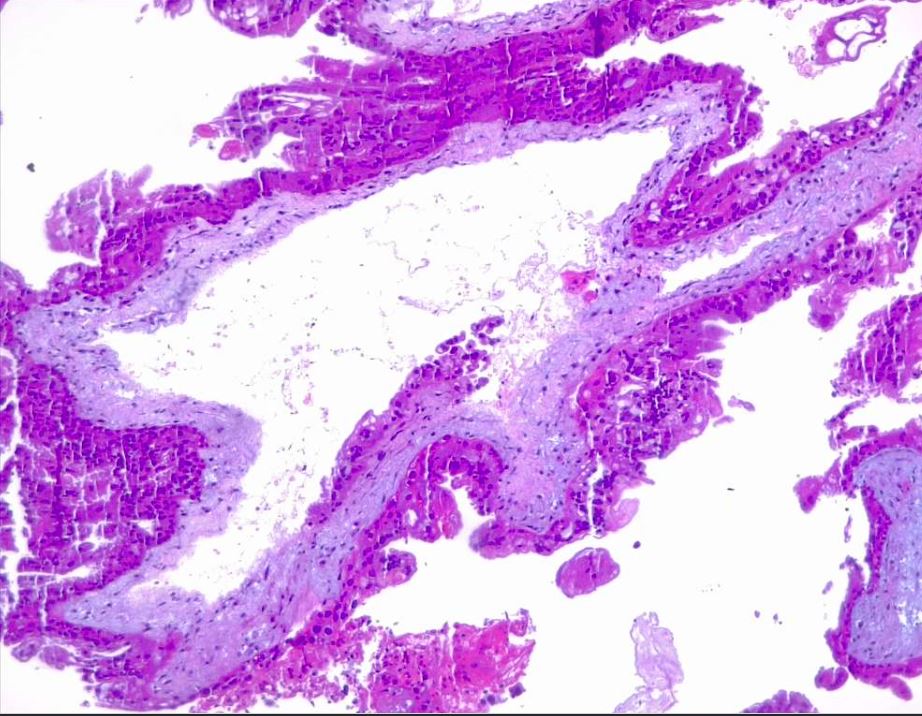

In contrast to complete moles, partial moles are compatible with early embryogenesis and, therefore, may exhibit fetal parts by imaging or gross examination. Less trophoblastic proliferation, more focal distribution of proliferative areas, and edematous villi in only some regions distinguish partial from complete moles. Histologically, villous trophoblastic inclusions may be seen (see Image. Partial Hydatiform Mole).[15] The slower rate of change from normal placental tissue to a hydatidiform morphology explains these characteristics.[15] Due to challenges in differentiation through imaging, ancillary studies and karyotyping may be necessary to supplement histology for definitive diagnosis. Unlike complete moles, partial moles exhibit positive p57 nuclear staining due to the presence of maternal genes.[16] Comprehension of the histological and genetic distinguishing characteristics between complete and partial moles is pivotal to accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

History and Physical

The presentation of the hydatidiform mole is somewhat different in a complete mole versus a partial mole. In fact, most partial moles are incidentally diagnosed from pathologic analyses of products of conception following spontaneous abortions.

Since the incorporation of ultrasonography early in prenatal care, the diagnosis of complete hydatidiform moles early in pregnancy has increased, mainly during the first trimester. The most common symptom of a complete mole, as high as 84% of patients in one study, is first-trimester vaginal bleeding, usually due to the molar tissue separating from the decidua.[17] The blood is often dark in appearance as opposed to bright red due to the accumulated blood products in the uterine cavity and the resultant oxidation and liquefaction of that blood. Another symptom of a complete molar pregnancy is hyperemesis or severe nausea and vomiting, which is due to the high level of β-hCG circulating in the bloodstream. Some patients also endorse passage of vaginal tissue described as grape-like clusters or vesicles.

Late findings of the disease, typically occurring around 14 to 16 weeks of pregnancy, include signs and symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, including tachycardia and tremors, again caused by the high levels of circulating β-hCG.[18] Other late sequelae are preeclampsia, which is pregnancy-induced hypertension and proteinuria or end-organ dysfunction, occurring typically after 34 weeks gestation. When a pregnant patient at less than 20 weeks gestation presents with signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, a complete molar pregnancy should be highly suspected. In very advanced cases, patients present with severe respiratory distress, possibly from embolism of the trophoblastic tissue into the lungs.[15]

The presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole is usually less dramatic than that of a complete mole. These patients typically present with symptoms similar to a threatened or spontaneous abortion, including vaginal bleeding. Since partial hydatidiform moles have fetal tissue, fetal heart tones may be auscultated or noted during fetal Doppler examination.

Over 50% of molar pregnancies are characterized by uterine size and date discrepancies noted during the physical examination. In a complete mole, the uterus is usually larger than the expected gestational date of the pregnancy. In contrast, in partial moles, uterine size can be smaller than the estimated gestational age.

Evaluation

Clinically, patients with a complete molar pregnancy may present with an enlarged uterus mimicking pregnancy, often with fundal height or uterine size greater than expected for gestational age, accompanied by markedly elevated β-hCG levels, frequently >100,000 mIU/mL.[19] Common presenting symptoms include persistent emesis, vaginal bleeding, pelvic pressure, and pain.[1] Although clinical signs, symptoms, and β-hCG levels help diagnose hydatidiform moles, ultrasonography is usually the initial screening method when molar pregnancy is suspected. Distinct images of a complete mole can be depicted in the first trimester of pregnancy.[11]

In a complete molar pregnancy, ultrasonography reveals anechoic cystic spaces resembling “grape clusters” with an echogenic mass and “snowstorm” appearance (see Image. Uterus Ultrasound, Molar Pregnancy). In contrast, partial molar pregnancies typically do not significantly affect uterine size; they exhibit slightly elevated β-hCG levels and contain fetal parts that may be visible on imaging.[11] In both partial and complete hydatidiform moles, symptoms of thyrotoxicosis may also manifest as a result of the increased β-hCG levels due to the molecular resemblance between β-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and hence cross-reactivity with the TSH receptor.[20] Nevertheless, the definitive diagnosis can be only made by histopathological examination of the tissue postoperatively, where complete moles exhibit edematous hydropic villi with circumferential and hyperplastic trophoblastic cells and partial moles exhibit large hydropic villi and small fibrotic villi.[5]

Treatment / Management

The initial treatment of a hydatidiform mole in patients who wish to preserve fertility is dilatation and curettage.[17] A 12- to 14-mm suction cannula is preferred, and an intravenous oxytocin infusion may be initiated at the onset of the procedure and continued for several hours postoperatively to enhance uterine contractility and decrease ongoing blood loss.[18] The risk of hemorrhage increases with uterine size; transfusion products should be available, especially when the uterus is larger than 16 weeks gestational size.[13] RhD factor is expressed on the trophoblast, so Rh immune globulin should be given to Rh-negative patients at the time of molar evacuation.[15]

Hysterectomy is an alternative to uterine evacuation if childbearing is complete.[21] In addition to eradicating the molar pregnancy, hysterectomy decreases the need for subsequent chemotherapy by eliminating the risk of local myometrial invasion as a cause of persistent disease.[22] Medical induction of labor and hysterotomy are not recommended for a molar evacuation since these methods increase maternal morbidity and the chance of developing GTN requiring chemotherapy.[23](A1)

Prophylactic administration of either methotrexate or actinomycin-D at the time of or immediately following molar evacuation is associated with a reduction in the incidence of postmolar GTN to 3% to 8%.[24] However, given the risks associated with these chemotherapeutic agents, they should be limited to clinical situations in which the risk of postmolar GTN is higher than usual or where reliable β-hCG follow-up is difficult.[15](A1)

Follow-up β-hCG monitoring every 1 to 2 weeks is essential for early diagnosis and management of postmolar GTN. After treatment of a gestational neoplastic process, follow-up β-hCG monitoring every month for at least 12 months is critical for surveillance of relapse. Reliable contraception must be used throughout this period.[15]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should be considered during an evaluation for a hydatidiform molar pregnancy include:

- Androgenetic/biparental mosaic conceptions

- Abnormal villous morphology

- Early abortus with trophoblastic hyperplasia [15]

- Hydropic abortus

- Hyperemesis gravidarum

- Hypertension

- Hyperthyroidism or other causes of thyrotoxicosis

- Malignant hypertension

- Placental mesenchymal dysplasia

- Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

Staging

Molar pregnancies are not staged, with staging reserved for patients progressing to GTN. If there is sufficient suspicion for a molar pregnancy that has progressed to GTN on initial diagnosis, usually guided by significant clinical symptoms or objective findings, then staging occurs concurrently with initial diagnosis and treatment.[15]

In brief, staging for GTN follows The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2000 guidelines as follows: [15]

- Stage I: Tumor strictly confined to the uterine corpus

- Stage II: Tumor extends to the adnexae or the vagina but is limited to genital structures

- Stage III: Tumor extends to the lungs, with or without genital tract involvement

- Stage IV: All other metastatic sites

Please see StatPearls' companion reference, "Gestational Trophoblastic Disease," for more information on GTN staging.

Prognosis

Earlier detection of molar pregnancy by ultrasonography has resulted in changes in clinical presentation and decreased morbidity from uterine evacuation.[15] Follow-up with β-hCG is essential for early diagnosis of GTN.[15] Once treated, the risk of recurrence or molar pregnancy in a later pregnancy is low, 0.6% to 2% after 1 molar pregnancy, although much increased after consecutive molar pregnancies.[25] However, of those diagnosed with a complete molar pregnancy, 15% to 20% of patients develop persistent GTN after suction curettage, requiring chemotherapy.[6]

Complications

The leading complication associated with molar pregnancies is the progression to GTN. β-hCG is an excellent biomarker of disease progression, response, and subsequent posttreatment surveillance. Thus, a plateaued or rising β-hCG level enables the early detection of the progression of complete hydatidiform mole and partial hydatidiform mole to GTN that occurs in 15% to 20% and 0.5% to 5% of cases, respectively.[18][13]

Consultations

Specialists who may be involved in the care of patients with hydatidiform moles include:

- Obstetrician-gynecologists

- Gynecologic oncologists

- Pathologist

- Radiologists

Deterrence and Patient Education

Clinical presentation of both complete and partial hydatidiform moles has changed drastically over the years. In the 1960s and 1970s, the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 16 weeks, and classic clinical signs were vaginal bleeding, uterine enlargement greater than expected for gestational age, theca-lutein cysts due to ovarian hyperstimulation by high serum β-hCG values, hyperemesis, preeclampsia, hyperthyroidism or thyrotoxicosis, and sometimes respiratory insufficiency.[26][9]

Currently, many patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis due to the wide use of ultrasonography in early pregnancy.[26] The mean gestational age at diagnosis is 10 to 12 weeks before the onset of classic clinical signs.[11] However, vaginal bleeding continues to be the most common presenting symptom, and it can occasionally present with passage of hydropic villi.[26] Because bleeding may be prolonged and occult, patients may be anemic at presentation.[11] Symptoms can be vague and resemble complaints often present in normal pregnancy. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that patients establish prenatal care, obtain regular ultrasounds, and remain compliant starting at the beginning of their pregnancies.

Vaginal bleeding and passage of tissue should prompt presentation to the emergency department or outpatient clinic. Furthermore, given that hydatidiform mole can be a premalignant lesion, it is pivotal for patients to remain compliant with postprocedure β-hCG surveillance to avoid unexpected progression to gestational trophoblastic disease. The use of reliable contraception is recommended while β-hCG values are being monitored. Frequent pelvic examinations are performed while β-hCG values are elevated to monitor the involution of the uterus and to aid in the early identification of vaginal metastases.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach is critical for managing a molar pregnancy, enhancing patient-centered care, safety, and outcomes through coordinated skills, strategies, and responsibilities. Typically, a molar pregnancy is first identified in the emergency or outpatient setting when a patient presents with first-trimester vaginal bleeding, nausea, and a positive pregnancy test. Physicians, advanced practitioners, and nurses must obtain and promptly assess transvaginal ultrasound results, with radiologists and ordering clinicians maintaining close communication to distinguish molar pregnancy from similar conditions like missed or incomplete abortion, which differ significantly in management. Once diagnosed, timely obstetrics/gynecology consultation is essential, as molar pregnancy requires surgical intervention and expedited care to mitigate hemorrhage risks. For effective surgical preparation and safety, tight communication between all interprofessional members is necessary.

Postevacuation, ongoing weekly β-hCG monitoring requires collaboration from outpatient clinicians, who emphasize follow-up adherence and help patients understand their results, improving compliance and early detection of possible disease recurrence. To avoid interference with β-hCG testing, patients are advised on reliable contraception, highlighting the role of pharmacists and primary care in providing patient education. Mental health support is equally important, as delayed childbearing and weekly monitoring can increase anxiety and depression. Clinicians across specialties should screen for these conditions and coordinate timely referrals to mental health professionals, ensuring comprehensive care and patient well-being.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gonzalez J, Popp M, Ocejo S, Abreu A, Bahmad HF, Poppiti R. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: Complete versus Partial Hydatidiform Moles. Diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Jul 17:12(7):. doi: 10.3390/diseases12070159. Epub 2024 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 39057130]

Candelier JJ. The hydatidiform mole. Cell adhesion & migration. 2016 Mar 3:10(1-2):226-35. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1093275. Epub 2015 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 26421650]

Brews A. A Follow-up Survey of the Cases of Hydatidiform Mole and Chorion-epithelioma treated at the London Hospital since 1912: (Section of Obstetrics and Gynæcology). Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1935 Jul:28(9):1213-28 [PubMed PMID: 19990373]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTantengco OAG, De Jesus FCC 2nd, Gampoy EFS, Ornos EDB, Vidal MS Jr, Cagayan MSFS. Molar pregnancy in the last 50 years: A bibliometric analysis of global research output. Placenta. 2021 Sep 1:112():54-61. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.07.003. Epub 2021 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 34274613]

Hui P, Buza N, Murphy KM, Ronnett BM. Hydatidiform Moles: Genetic Basis and Precision Diagnosis. Annual review of pathology. 2017 Jan 24:12():449-485. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28135560]

Jauniaux E, Memtsa M, Johns J, Ross JA, Jurkovic D. New insights in the pathophysiology of complete hydatidiform mole. Placenta. 2018 Feb:62():28-33. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.12.008. Epub 2017 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 29405964]

La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Parazzini F, Fasoli M, Decarli A, Gallus G, Tognoni G. Risk factors for gestational trophoblastic disease in Italy. American journal of epidemiology. 1985 Mar:121(3):457-64 [PubMed PMID: 2990199]

Fisher RA, Maher GJ. Genetics of gestational trophoblastic disease. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2021 Jul:74():29-41. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.01.004. Epub 2021 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 33685819]

Soper JT. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: Current Evaluation and Management. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021 Feb 1:137(2):355-370. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004240. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33416290]

Poaty H, Coullin P, Leguern E, Dessen P, Valent A, Afoutou JM, Peko JF, Candelier JJ, Gombé-Mbalawa C, Picard JY, Bernheim A. [Cytogenomic studies of hydatiform moles and gestational choriocarcinoma]. Bulletin du cancer. 2012 Sep:99(9):827-43. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2012.1621. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22877883]

Lukinovic N, Malovrh EP, Takac I, Sobocan M, Knez J. Advances in diagnostics and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Radiology and oncology. 2022 Dec 1:56(4):430-439. doi: 10.2478/raon-2022-0038. Epub 2022 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 36286620]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaur B. Pathology of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2021 Jul:74():3-28. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.02.005. Epub 2021 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 34219021]

Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS. Gestational trophoblastic disease. Lancet (London, England). 2010 Aug 28:376(9742):717-29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60280-2. Epub 2010 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 20673583]

Szulman AE, Surti U. The syndromes of hydatidiform mole. II. Morphologic evolution of the complete and partial mole. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1978 Sep 1:132(1):20-7 [PubMed PMID: 696779]

Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, Berkowitz RS, Xiang Y, Golfier F, Sekharan PK, Lurain JR, Massuger L. Diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease: 2021 update. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2021 Oct:155 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):86-93. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13877. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34669197]

Zhao Y, Cai L, Huang B, Yin X, Pan D, Dong J, Zheng L, Chen H, Lin J, Shou H, Zhao Z, Jin L, Zhu X, Cai L, Zhang X, Qian J. Reappraisal and refined diagnosis of ultrasonography and histological findings for hydatidiform moles: a multicentre retrospective study of 821 patients. Journal of clinical pathology. 2024 Jul 24:():. pii: jcp-2024-209638. doi: 10.1136/jcp-2024-209638. Epub 2024 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 39048306]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSato A, Usui H, Shozu M. Comparison between vacuum aspiration and forceps plus blunt curettage for the evacuation of complete hydatidiform moles. Taiwanese journal of obstetrics & gynecology. 2019 Sep:58(5):650-655. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2019.07.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31542087]

Lurain JR. Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Dec:203(6):531-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.073. Epub 2010 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 20728069]

Coyle C, Short D, Jackson L, Sebire NJ, Kaur B, Harvey R, Savage PM, Seckl MJ. What is the optimal duration of human chorionic gonadotrophin surveillance following evacuation of a molar pregnancy? A retrospective analysis on over 20,000 consecutive patients. Gynecologic oncology. 2018 Feb:148(2):254-257. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.008. Epub 2017 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 29229282]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWalkington L, Webster J, Hancock BW, Everard J, Coleman RE. Hyperthyroidism and human chorionic gonadotrophin production in gestational trophoblastic disease. British journal of cancer. 2011 May 24:104(11):1665-9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.139. Epub 2011 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 21522146]

Capozzi VA, Butera D, Armano G, Monfardini L, Gaiano M, Gambino G, Sozzi G, Merisio C, Berretta R. Obstetrics outcomes after complete and partial molar pregnancy: Review of the literature and meta-analysis. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2021 Apr:259():18-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.01.051. Epub 2021 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 33550107]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTidy JA, Gillespie AM, Bright N, Radstone CR, Coleman RE, Hancock BW. Gestational trophoblastic disease: a study of mode of evacuation and subsequent need for treatment with chemotherapy. Gynecologic oncology. 2000 Sep:78(3 Pt 1):309-12 [PubMed PMID: 10985885]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhao P, Lu Y, Huang W, Tong B, Lu W. Total hysterectomy versus uterine evacuation for preventing post-molar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia in patients who are at least 40 years old: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC cancer. 2019 Jan 7:19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5168-x. Epub 2019 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 30612545]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWang Q, Fu J, Hu L, Fang F, Xie L, Chen H, He F, Wu T, Lawrie TA. Prophylactic chemotherapy for hydatidiform mole to prevent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Sep 11:9(9):CD007289. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007289.pub3. Epub 2017 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 28892119]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSebire NJ, Fisher RA, Foskett M, Rees H, Seckl MJ, Newlands ES. Risk of recurrent hydatidiform mole and subsequent pregnancy outcome following complete or partial hydatidiform molar pregnancy. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2003 Jan:110(1):22-6 [PubMed PMID: 12504931]

Lok C, Frijstein M, van Trommel N. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2021 Jul:74():42-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.12.001. Epub 2020 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 33422446]