Introduction

Vulvodynia is a complex and often debilitating condition. According to the current definition by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), vulvodynia is characterized by vulvar pain lasting at least 3 months without a clearly identifiable cause, although potential associated factors may exist. Vulvodynia is considered an idiopathic pain disorder and is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Symptoms can vary in intensity and location, presenting as burning, irritation, or hypersensitivity, which can disrupt daily activities and intimate relationships. Although the exact origins of vulvodynia remain unclear, research suggests a multifactorial etiology, including nerve dysfunction, inflammation, and hormonal imbalances. A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach is essential for timely diagnosis and effective management, improving both physical and emotional well-being.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact cause of vulvodynia remains unknown, and ongoing research aims to identify potential contributing factors. Possible contributing causes include nerve injury or irritation affecting the transmission of pain from the vulva to the spinal cord, an increase in the number and sensitivity of nerve fibers in the vulva, elevated levels of inflammatory substances such as cytokines, abnormal responses to environmental factors, genetic susceptibility, and pelvic floor muscle weakness, spasms, or instability.[1]

Vulvodynia can be classified as either generalized or localized, depending on the location of the pain. Symptoms may arise spontaneously or be triggered by touch or pressure. The condition can be primary, occurring throughout a patient's life, or secondary, developing later, such as with a new partner. Additionally, vulvodynia can vary in timing, presenting as intermittent, persistent, constant, immediate, or delayed pain.[2][3]

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of vulvodynia was reported as 3.1% in 2012 by Reed.[4] In 2014, the incidence was 4.2 cases per 100 woman-years, varying by age, ethnicity, and marital status. An independent population-based study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reported a point prevalence of 3% to 7% among reproductive-aged women.[5][6] Three of the studies included clinical confirmation. By age 40, 7% of American women will experience symptoms consistent with vulvodynia. Notably, only 1.4% of women who sought medical care received a correct diagnosis.[5]

Pathophysiology

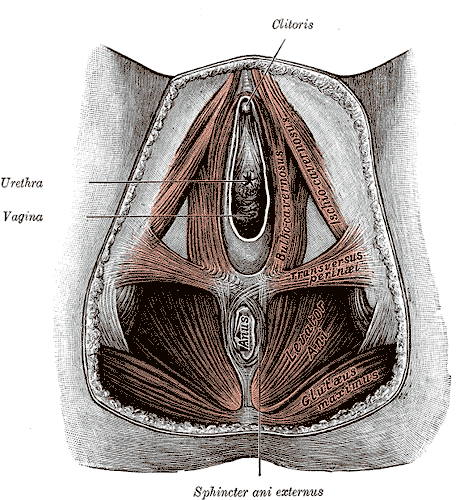

A comprehensive understanding of the vulva and vulvar vestibule anatomy is crucial for accurately diagnosing and managing vulvodynia. The vulva includes external genital structures such as the labia, clitoris, and vestibule, which houses sensitive nerve endings and glandular openings (see Image. Anatomy of the Female Perineum).

The vulva is the external female genitalia, consisting of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoral hood, clitoris, and vestibule. The anterior labial branches of the ilioinguinal nerve, the genitofemoral nerve, and branches of the pudendal nerve innervate the vulva. The pudendal nerve divides into 3 branches near the medial aspect of the ischial tuberosity, as mentioned below.

- The dorsal nerve of the clitoris.

- The perineal nerve, which innervates the labia majora and perineum.

- The inferior rectal nerve, which innervates the perianal area.

Additionally, the pudendal nerve also innervates the external anal sphincter and the deep muscles of the urogenital triangle.

The pelvic floor muscles are classified into 3 categories, as mentioned below.

- Superficial pelvic floor muscles: These muscles include the bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial transverse perineal muscles, which are collectively known as the urogenital diaphragm. These muscles control sexual function, such as clitoral engorgement, vaginal closure, and reflexive response that enhance sexual pleasure. They also facilitate the closure of the urethra and anus for continence.

- Middle layer: This layer consists of the sphincter urethra and the deep, transverse perineal muscle.

- Deep pelvic floor muscles: These muscles are sometimes referred to as the anal triangle. These include the levator ani (composed of the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis) and the coccygeus. Associated pelvic and hip muscles include the piriformis, obturator internus, and gluteus maximus. The perineal body serves as the central tendon and attachment site for the pelvic floor muscles. These muscles support the abdominal viscera, provide pelvic and spinal stability, assist in respiration, facilitate sphincteric closure for the bowel and bladder, and contribute to sexual function.

The internal pudendal artery, vein, and nerve pass through the Alcock canal, where they provide neurovascular support to the pelvic floor musculature.

History and Physical

A detailed medical history is essential for diagnosing vulvodynia, as it helps differentiate the condition from other potential causes of vulvar pain. Clinicians should inquire about the onset, duration, and nature of the pain, including whether it is constant or intermittent, localized or generalized. Identifying triggers, such as sexual activity, sitting, or tight clothing, can provide valuable insight into potential exacerbating factors.

A comprehensive history should also include information on previous treatments, their effectiveness, and any underlying conditions, such as infections, hormonal imbalances, or pelvic floor dysfunction. Psychological factors, such as anxiety, depression, or stress, should be assessed as they can contribute to or exacerbate symptoms. Additionally, a review of medications and allergies is essential. Gathering this information helps establish a more accurate diagnosis and guides the development of an appropriate treatment plan.

The patient should undergo a thorough gynecological examination. After investigating and treating all potential infectious, inflammatory, hormonal, neoplastic, and neurological causes, a visual inspection of the vulva and vulvar vestibule should be conducted.[1]

- Cotton swab evaluation: The clinician should ask the patient, "Where does it hurt?" and "Does it hurt before touch?" Starting from the outside and moving inward toward the vestibule, the clinician should mark the areas to identify the location of the pain. The evaluation should begin with the inner thigh, followed by the labia majora, inner labial sulcus, clitoris, clitoral hood, perineum, and various sites within the vestibule. The patient should be asked to rate their pain on a scale of 1 to 10.

- Neurosensory assessment: A pinprick examination should be performed in the same locations as the cotton swab assessment. The clinician should note whether the response is normal, hypersensitive, or involves sharp, burning, or shooting pain.

- Pelvic muscle examination: The clinician should begin with the puborectalis and progress toward the other pelvic muscles.

- Evaluation of pain comorbidities: Conditions such as interstitial cystitis, endometriosis, temporomandibular joint syndrome, and chronic headaches should be assessed.

- Assessment of factors contributing to pain: The clinician should evaluate sleep disturbances and relationship issues, as well as physical, emotional, and sexual functioning.[7]

Evaluation

Laboratory tests specific to vulvodynia do not exist, as it is a diagnosis of exclusion. If vulvodynia is suspected, additional diagnostic tests, such as cultures or biopsies, may be conducted to rule out other conditions, such as infections, dermatological disorders, or neoplastic changes. These tests help confirm that the symptoms are not due to underlying conditions and support the diagnosis of vulvodynia as a pain disorder of exclusion.

Treatment / Management

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach. Validating the individual's pain complaints is crucial, as many women have struggled in silence for a long time or have seen multiple practitioners without finding effective treatment.[8] Different clinicians may be involved in the care of the patient. An appropriate interprofessional healthcare team may include a gynecologist with a special interest in vulvovaginal health, often involved in societies such as the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the ISSVD, as well as a dermatologist, neurologist, pain management specialist, urologist, and a physical therapist specializing in women's health.[9][10][11] (B3)

Treatment Modalities

- Vulvar self-care includes avoiding irritants, either directly or through dietary modifications.

- Oral "pain-blocking" medications can effectively alleviate vulvodynia pain. These medications include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and anticonvulsants.

- TCAs are the most commonly used, with amitriptyline and nortriptyline being the most frequently prescribed.

- Nortriptyline is often the preferred choice due to its fewer adverse effects. The prescribed dosage is lower than that used for treating depression. Treatment should start with very low doses and gradually increase to minimize adverse effects.

- Commonly used SNRIs include duloxetine and venlafaxine.

- Anticonvulsants typically prescribed are gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate.

- Topical medications applied directly to the vulva can help alleviate pain, provided they do not contain allergens. These medications are typically compounded and may include lidocaine, estrogen, testosterone, or gabapentin, either alone or in combination.

- Women's health physical therapy has become an effective component of vulvodynia treatment. Most patients should be referred for evaluation and management of pelvic floor muscle weakness and spasms. Treatment approaches may include targeted exercises, massage, soft tissue mobilization, and joint mobilization.[12][13][14]

- Nerve blocks, psychotherapy, mindfulness, yoga, and neurostimulation may also be beneficial in treatment.[15]

- Surgery is generally reserved for cases of provoked vestibular vulvodynia and specific patients. Vaginal advancement involves removing the vestibule and the affected area of the vagina. Following the surgery, physical therapy and the use of dilators are recommended to support recovery. (A1)

Differential Diagnosis

A thorough differential diagnosis of vulvodynia is essential to rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms of vulvar pain. A careful assessment of clinical features, patient history, and diagnostic tests helps distinguish vulvodynia from infections, dermatological conditions, and other gynecological or urological conditions.

- Infections: Vulvovaginal candidiasis, atypical candidiasis, bacterial vaginitis, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes.

- Inflammation: Lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, contact dermatitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.

- Neoplastic disorders: Squamous cell carcinoma.

- Neurological disorders: Pudendal, genitofemoral or ilioinguinal nerve injury, nerve entrapment, neuropathy, and Tarlov cysts.

- Trauma-related causes: Straddle injuries, female genital cutting, and motor vehicle accidents.

- Hormonal deficiencies: Estrogen deficiency.

- Nonspecific symptoms: Vaginal burning and irritation.

- Iatrogenic causes: Vulvar and vaginal pain.[11]

Prognosis

The prognosis of vulvodynia varies, with some individuals experiencing symptom relief over time while others may face persistent pain. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary treatment approach can significantly improve outcomes. Although a universal cure does not exist, many patients achieve effective symptom management through a combination of medical, physical, and psychological therapies. Addressing contributing factors such as nerve dysfunction or musculoskeletal issues can lead to long-term relief. Emotional and social support also play a vital role in enhancing quality of life. With appropriate care, many individuals experience reduced pain intensity and improved daily functioning.

Complications

Vulvodynia can lead to significant physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. Chronic pain may disrupt daily activities, exercise, and sexual function, leading to distress and strained intimate relationships. Many patients experience anxiety, depression, and a diminished quality of life due to persistent discomfort and frustration with delayed diagnosis. Without proper management, vulvodynia can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction, exacerbating pain over time. Social isolation and feelings of hopelessness are also common, underscoring the need for comprehensive, multidisciplinary care. Early intervention and patient education are crucial in preventing long-term complications and improving overall well-being.

Consultations

Consultations for vulvodynia may require referrals to specialists such as gynecologists, pain management experts, dermatologists, or pelvic floor therapists, depending on the complexity of the case. Interdisciplinary collaboration is often essential to provide a comprehensive approach, addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of the condition. Psychologists or counselors may be consulted to help manage the emotional impact of chronic pain, while physical therapists can support pelvic floor rehabilitation. Early referrals to the appropriate specialists can improve diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment plans, and enhance patient outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education and awareness are essential for improving awareness, early diagnosis, and effective management of vulvodynia. Clinicians should receive training to recognize vulvodynia as a diagnosis of exclusion and understand its multifactorial nature. By educating patients about potential triggers, lifestyle modifications, and treatment options, clinicians can empower them to manage symptoms proactively. Open communication between healthcare providers and patients is key to reducing stigma and ensuring timely intervention.

Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration among healthcare providers, including physical therapy and psychological support, enhances treatment outcomes. Public health initiatives and professional education programs can further raise awareness, ultimately improving patient quality of life and reducing the burden of undiagnosed or mismanaged vulvodynia.

Pearls and Other Issues

Research on vulvodynia is ongoing, as 25% of adult Americans suffer from a chronic pain condition. Unfortunately, patients with chronic pain are often neglected and undertreated. Vulvodynia can be severe and debilitating, yet the scientific evidence supporting treatment regimens is limited, with few randomized controlled trials available. Treatment outcomes vary across studies, but most women experience improvement with appropriate care. Clinicians should be encouraged to take their patients' concerns seriously and recognize that vulvodynia is a real condition. If a practitioner is unsure how to treat it or lacks the necessary education and experience, they should refer to the National Vulvodynia Association for guidance on finding a qualified healthcare professional.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The cause of vulvodynia remains unknown, and its treatment continues to be challenging. Management requires an interprofessional treatment approach, with the patient's report of pain and its severity taken seriously. Many women have struggled in silence for a long time or have consulted numerous clinicians without achieving pain relief. The care of these patients often involves multiple practitioners. An interprofessional healthcare team may include a gynecologist with a special interest in vulvovaginal health (often affiliated with societies such as ISSWSH and ISSVD), a dermatologist, a nurse practitioner, a neurologist, a pain management specialist, a urologist, and a physical therapist specializing in women's health.[9]

Effective treatment strategies must be individualized. Unfortunately, despite a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach, some patients may experience recurrent pain that significantly impacts their lifestyle and interpersonal relationships.[16][17] Ongoing research is essential to advancing the treatment of vulvodynia. Continued investigation into its pathophysiology, potential biomarkers, and innovative therapies will aid in developing more targeted, evidence-based approaches to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anatomy of the Female Perineum. The female perineum comprises key anatomical structures, including the clitoris, urethra, vagina, sphincter ani externus, anus, gluteus maximus, levator ani, and transversus perinei.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Vieira-Baptista P, Lima-Silva J, Pérez-López FR, Preti M, Bornstein J. Vulvodynia: A disease commonly hidden in plain sight. Case reports in women's health. 2018 Oct:20():e00079. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2018.e00079. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30245974]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDias-Amaral A, Marques-Pinto A. Female Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder: Review of the Related Factors and Overall Approach. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2018 Dec:40(12):787-793. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675805. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30428492]

Schlaeger JM, Glayzer JE, Villegas-Downs M, Li H, Glayzer EJ, He Y, Takayama M, Yajima H, Takakura N, Kobak WH, McFarlin BL. Evaluation and Treatment of Vulvodynia: State of the Science. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2023 Jan:68(1):9-34. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13456. Epub 2022 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 36533637]

Reed BD. Vulvodynia: diagnosis and management. American family physician. 2006 Apr 1:73(7):1231-8 [PubMed PMID: 16623211]

Reed BD, Haefner HK, Harlow SD, Gorenflo DW, Sen A. Reliability and validity of self-reported symptoms for predicting vulvodynia. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2006 Oct:108(4):906-13 [PubMed PMID: 17012453]

Torres-Cueco R, Nohales-Alfonso F. Vulvodynia-It Is Time to Accept a New Understanding from a Neurobiological Perspective. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021 Jun 21:18(12):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126639. Epub 2021 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 34205495]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, Feranec J. Evaluation and Treatment of Female Sexual Pain: A Clinical Review. Cureus. 2018 Mar 27:10(3):e2379. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2379. Epub 2018 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 29805948]

Webber V, Bajzak K, Gustafson DL. Regarding Webber, V., Bajzak, K. and Gustafson, D. L. (2023). The impact of rurality on vulvodynia diagnosis and management: Primary care provider and patient perspectives. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 28 (3), 107-115. Canadian journal of rural medicine : the official journal of the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada = Journal canadien de la medecine rurale : le journal officiel de la Societe de medecine rurale du Canada. 2025 Jan 1:30(1):48-49. doi: 10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_62_24. Epub 2025 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 40052781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, Bergeron S, Pukall C, Zolnoun D, Coady D, consensus vulvar pain terminology committee of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS). 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016 Apr:13(4):607-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167. Epub 2016 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 27045260]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, Bergeron S, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S. Vulvodynia: Assessment and Treatment. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016 Apr:13(4):572-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.020. Epub 2016 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 27045258]

Vasileva P, Strashilov SA, Yordanov AD. Aetiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of vulvodynia. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. 2020 Mar:19(1):44-48. doi: 10.5114/pm.2020.95337. Epub 2020 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 32699543]

Newman DK, Lowder JL, Meister M, Low LK, Fitzgerald CM, Fok CS, Geynisman-Tan J, Lukacz ES, Markland A, Putnam S, Rudser K, Smith AL, Miller JM, Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium. Comprehensive pelvic muscle assessment: Developing and testing a dual e-Learning and simulation-based training program. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2023 Jun:42(5):1036-1054. doi: 10.1002/nau.25125. Epub 2023 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 36626146]

Falsetta ML, Foster DC, Bonham AD, Phipps RP. A review of the available clinical therapies for vulvodynia management and new data implicating proinflammatory mediators in pain elicitation. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017 Jan:124(2):210-218. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14157. Epub 2016 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 27312009]

Loflin BJ, Westmoreland K, Williams NT. Vulvodynia: A Review of the Literature. The Journal of pharmacy technology : jPT : official publication of the Association of Pharmacy Technicians. 2019 Feb:35(1):11-24. doi: 10.1177/8755122518793256. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 34861006]

Queiroz JF, Sarmento ACA, Aquino ACQ, de Souza ATB, de Medeiros KS, Falsetta ML, Gonçalves AK. Psychotherapy and Psychotherapeutic Techniques for the Treatment of Vulvodynia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2025 Feb 24:():. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000881. Epub 2025 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 39993259]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRosen NO, Dawson SJ, Brooks M, Kellogg-Spadt S. Treatment of Vulvodynia: Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Approaches. Drugs. 2019 Apr:79(5):483-493. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01085-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30847806]

Coady D, Kennedy V. Sexual Health in Women Affected by Cancer: Focus on Sexual Pain. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Oct:128(4):775-91. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001621. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27607852]