Introduction

Historically, uveitis is a term used to describe inflammatory processes of the portion of the eye known as the uvea, which is composed of the iris, ciliary body, and the choroid; however, any area of the eye can be inflammed. Uveitis can be further subdivided into anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis based on the primary anatomical location of the inflammation in the eye. Symptoms and consequences can range from pain and conjunctival injection to complete vision loss. Anterior uveitis is epitomized by the anterior segment being the predominate site of inflammation. Intermediate uveitis is defined by inflammation of the vitreous cavity and pars plana, while posterior uveitis involves the retina and choroid. Inflammation in panuveitis includes all layers.[1]

Anatomic locations of uveitis:

- Anterior

- Intermediate

- Posterior

- Panuveitis

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Uveitis is most often idiopathic but has been associated with traumatic, inflammatory, and infectious processes. Patients may present with concurrent systemic symptoms or infectious diseases to suggest an etiology affecting more than just the eye. Idiopathic cases of uveitis account for 48 to 70% of uveitis cases.[2] Systemic inflammatory disorders commonly associated with anterior uveitis include: HLA-B27-associated entities, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, Behcet's disease (BD) or tubulo-interstitial nephritis (TINU). Multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, and TINU are causes of intermediate uveitis with systemic manifestations, while Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, leukemia, lupus, BD, and multiple sclerosis can cause a posterior uveitis with systemic manifestations. BD is a systemic vasculitis that can also present with pan-uveitis.[3] Infectious processes are thought to account for approximately 20% of all uveitis cases but underlying causes can vary geographically [4]. Infectious causes include viruses (HSV, VZV, CMV), bacteria (endophthalmitis, syphilis, tuberculosis, etc), or parasites/worms (toxoplasmosis, Lyme Disease, toxocara, Bartonella sp. or other atypical infections).[5][6]

Epidemiology

Uveitis can affect people of all ages and can vary significantly by geographic location and age of the patient [7]. In a study done from 2006 to 2007, the incidence of uveitis was 24.9 cases per 100,000 persons. Prevalence rates for 2006 and 2007 came in at 57.5 and 58 respectively per 100,000 persons [8]. There was no difference in the incidence rate between men and women, but women had a higher prevalence [8]. Anterior uveitis is the most prevalent form, accounting for approximately 50% of uveitis cases, while posterior uveitis is the least common. Ongoing inflammation seen in untreated uveitis and complications related to this uncontrolled inflammation are estimated to be responsible for approximately 10% of the blindness in the United States.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of uveitis in general is not well understood. Groups have hypothesized that trauma to the eye can cause cell injury or death which leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines leading to a post-traumatic uveitis. Uveitis caused by inflammatory diseases is thought to be due to molecular mimicry, where an infectious agent cross-reacts with ocular-specific antigens. Vision-threatening inflammation is mediated by CD4 Th1 cells. Normally, only activated lymphocytes are allowed past the blood-retina barrier, thus decreasing sensitization of naïve T cells to ocular proteins. Researchers have proposed there is molecular mimicry between retinal S-Ag peptides and a peptide from disease associated HLA-B antigens, which leads to targeting of ocular proteins and inflammatory response.[9]

History and Physical

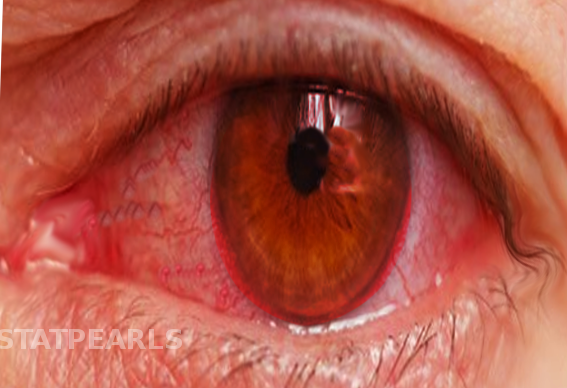

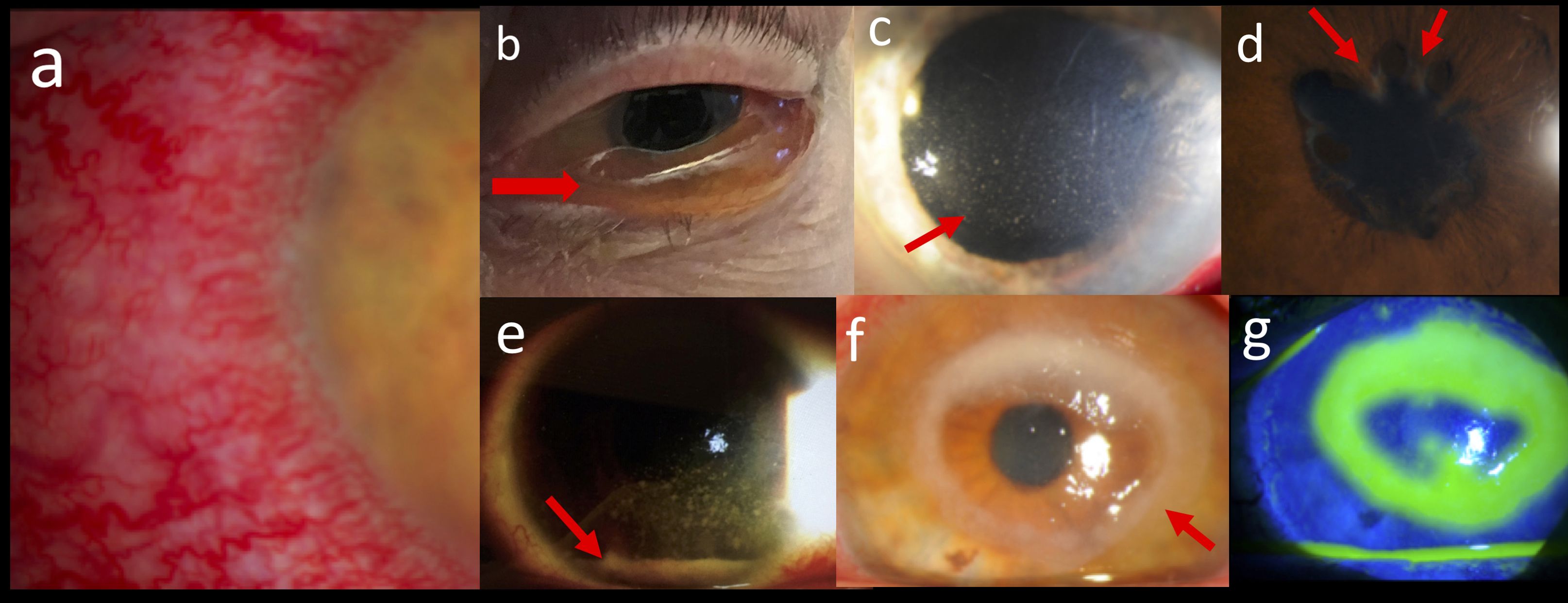

A complete past medical, family, and ophthalmic history (specifically surgical) is necessary for diagnosis. A full review of systems may also help identify a systemic disease with ocular manifestations. Symptoms will vary depending on the structure that is inflamed. Acute anterior uveitis can be unilateral or bilateral (an autoimmune disease) with symptoms including pain, blurred vision, photophobia, and circumlimbal injection (ciliary flush, Figure 1a). In anterior uveitis, the affected pupil maybe constricted or irregular in shape when compared to the unaffected eye due to posterior synechia (iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule, red arrows in Figure 1d) formation. Intermediate uveitis is not usually associated with pain but can cause blurred vision and floaters, while posterior uveitis more often presents with vision loss and/or dysphotopsias. Panuveitis is usually a combination of all of these symptoms due to multiple areas of the eye being affected simultaneously.

Physical exams should include visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Pinhole visual acuity is also a good tool to use when the patient may have left their glasses at home or the patient is thought to have an untreated refractive error. This can be accomplished quite easily by poking a small hole through a styrofoam cup and having the patient look through that single hole to read the visual acuity chart. Noting an afferent pupillary defect may also help guide the differential diagnosis due to optic nerve involvement.

On slit lamp exam, local or diffuse ciliary flush may be seen. One would also expect to see cell and flare in the anterior chamber. "Cell" refers to a collection of white blood cells in the anterior chamber; the cells may be so dense that it has settled to form a white, dependent, hypopyon (layered white blood cells within the anterior chamber, Figure 1e), signifying severe inflammation that should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist promptly. The differential diagnosis of a hypopyn is significant as HLA-B27-associated anterior uveitis, Behcet's Disease, endophthalmitis, and masqueraders define the most significant causes. Flare is an increased protein concentration within the aqueous humor from vascular changes resulting in a "foggy" appearance within the anterior chamber. Using the black background of the pupil, a foggy appearance for flare and/or small, floating white cells can be appreciated with an angled beam of light with maximum slit lamp magnification [2]. Counting these cells within a 1mm x 1mm beam helps quantify and standardize the amount of inflammation within the anterior chamber as defined by the SUN classification [1]. Keratic precipitates (Figure 1c) may also be found attached to the inside lining of the corneal endothelium. In severe cases, there maybe some spill-over inflammation into the anterior vitreous but the major inflammatory focus should be the anterior chamber in anterior uveitis.

Other ocular pathology such as posterior synechiae, cataract formation, rubeosis (blood vessels on the iris surface), and band keratopathy may suggest a longstanding inflammatory process or prior event if found in the unaffected eye. These findings can help aide in clarifying the differential diagnosis as a unilateral anterior uveitis versus a non-simulutaneous, bilateral anterior uveitis as they can have a different differential diagnosis.

In intermediate uveitis, inflammatory cells can be seen suspended within the vitreous. These cells are appreciated similar to that of anterior chamber cells but with the slit lamp focused behind the lens. Larger inflammatory collections known as "snowballs" may also be identified within the vitreous. An indirect examination with special attention to the pars plana is crucial in making the diagnosis as pars plana exudates known as a "snowbank" may be found. A fluorescein angiogram (ocular dye-based imaging modality) may find vascular ferning (vascular leakage). In some cases, there can be some spill-over of inflammation into the anterior chamber blurring the lines of differentiation of an anterior versus intermediate uveitis.

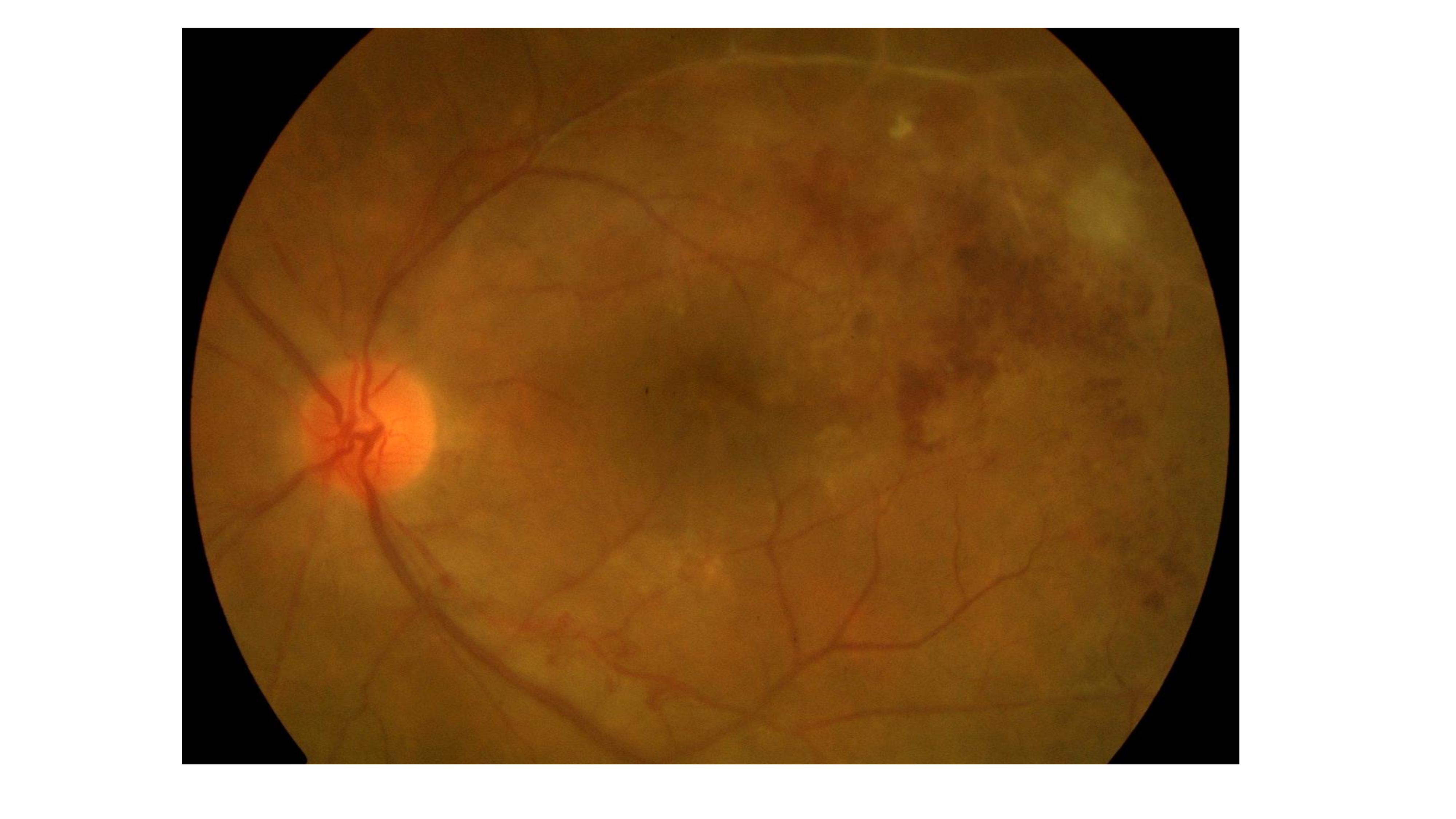

Posterior uveitis is defined by lesions of the retina and choroid and may include focal chorioretinal spots, retinal whitening, retinal detachments, retinal vasculitis, and optic nerve edema. Ocular history, such as a recent intraocular procedure, make retinal hemorrhages and vasculitis much more concerning for an infectious etiology [10].

Most Common Key Signs/Symptoms:

A. Anterior uveitis:

Symptoms: red, painful eye

Signs: anterior chamber cell and flare, posterior synechiae, keratic precipitates

B. Intermediate uveitis:

Symptoms: worsening floaters, decreased vision

Signs: vitreous cell and haze, snowballs, pars plana snowbank, cystoid macular edema

C. Posterior Uveitis:

Symptoms: worsening vision, visual field changes

Signs: chorioretinal lesions, retinal whitening, vascular sheathing

D. Panuveitis:

Symptoms: red, painful eye; severely depressed visual acuity; floaters

Signs: anterior chamber cell and flare, vitreous cell and haze, chorioretinal lesions, retinal whitening

Evaluation

The first episode of anterior uveitis usually may not require a laboratory workup but recurrence should prompt further evaluation. Intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis warrant further evaluation with differential diagnosis-guided laboratory evaluation due to the association with systemic diseases and the more profound risk of permanent vision loss. If the patient experiences recurrent anterior uveitis, further workup may be indicated to rule out an underlying autoimmune or infectious process.

For anterior uveitis, consider testing for HLA-B27 typing, FTA/RPR, serum ACE/lysozyme, chest x-ray, and quantiferon gold. Intermediate uveitis should be guided by other systemic symptoms and risk factors but should include FTA/RPR, chest X-ray, ACE/lysozyme, and quant gold. Neuroimaging for multiple sclerosis should be considered in the proper demographic population. Findings and other associated systemic manifestations should guide laboratory selection. As anywhere else in the body, syphilis is the "great masquerader" and should be considered in all cases of uveitis. A detailed differential diagnosis can be found in Diagnosis and Treatment of Uveitis (ed. Foster and Vitale), or for children, Pediatric Retina (ed. ME Hartnett).

Although rare (<0.5% of cases at tertiary referral centers), a patient's current medications may cause uveitis [11]. The antiviral, cidofovir, for example, can cause anterior uveitis with or without hypotony in a significant number of patients.[12] Checkpoint inhibitors (newer cancer drugs) are also becoming a well-known cause of mild to severe anterior, posterior, or panuveitis [13].

Key diagnoses to rule out in every case of uveitis: syphilis, sarcoid, and tuberculosis

Use the following laboratory tests: FTA AND RPR, ACE/lysozyme, chest x-ray, and quantiferon gold or PPD

Treatment / Management

Treatment aims at eliminating inflammation and pain with steroids and topical cycloplegics. Any additional therapies depend on associated processes. For example, anti-viral medications are necessary in herpetic uveitis, while bactrim can be used in toxoplasmic chorioretinitis. Antimetabolite, biologics, and other immunosuppressive medications (e.g., methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, adalimumab, and infliximab) are often necessary for chronic, non-infectious cases, especially in cases associated with systemic inflammatory diseases. However, these agents should only be prescribed by providers specifically trained in their use and attuned to their side effect profile.

For anterior uveitis, the most common, therapy consists of topical corticosteroids and cycloplegics. Steroids should be tapered according to clinical response to minimize rebound inflammation. Subsequent follow up should be established to monitor for resolution of inflammation and monitor IOP due to the potential of a precipitous rise in IOP with prolonged topical steroid use.

Cycloplegics, typically atropine or cyclogyl, are used to minimize pain by reducing spasm of the ciliary body and prevent and/or lyse posterior synechiae (adhesions of the iris to the lens capsule). These medications are typically applied twice daily until inflammation has resolved or has significantly decreased before cessation.[2]

Intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis treatment is much more complex and should be guided by ophthalmologists, specifically uveitis specialists, when possible.

Differential Diagnosis

There are several other causes for a painful, red eye with vision changes/loss that are frequently encountered in the primary care and ER setting. It is important to keep a broad differential when evaluating an eye complaint as there can be significant overlap with patient's symptoms. The following causes of a red, painful eye require special skills that must be used in each case to differentiate them. These special skills include visual acuity testing, IOP measurements, slit lamp biomicroscopy, and fluoroscein staining.

Conjunctivitis can present as a painful red eye with photophobia. Bacterial conjunctivitis can present with purulent discharge which is not present in uveitis. Patients with viral or allergic conjunctivitis will usually have serous discharge; however, they can also be without discharge. Follicles of the palpebral conjunctiva and the lack of anterior chamber inflammation help make the diagnosis of conjunctivitis. Chemosis (swelling of the conjunctiva, Figure 1b) is also a finding found in conjunctivitis but not in uveitis.

Keratitis is significant inflammation of the cornea. It frequently presents with pain, photophobia, and perilimbic injection (Figure 1a) and is most commonly seen in patients with a history of contact lens use. In keratitis, the cornea is often clouded if not frankly opaque (i.e. corneal ulcer, Figure 1f with ring infiltrate), which is not seen in uveitis. Also, the pupil is usually normal in shape in keratitis but maybe constricted in anterior uveitis due to posterior synechiea formation (Figure 1d). Fluoroscein dye will identify a brightly staining epithelial defect when viewed under a cobalt light (Figure 1g, same patient as in 1f with epithelial defect identified by fluorescein dye). The presence of stromal whitening (corneal infiltrate, Figure 1f) that is seen with keratitis is not seen with corneal abrasions.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can present as a painful red eye with a change in vision. The patient may complain of a unilateral headache and maybe nauseous even to the point of vomiting. The affected pupil is often mid-dilated and poorly reactive to light. The IOP will be significantly increased in acute angle closure glaucoma and is typically seen in most causes of uveitis [14]. However, an elevated IOP in the setting of a unilateral anterior uveitis is seen with herpes infections, so a slit lamp examination specifically looking for anterior chamber cell and keratic precipitates (punctate spots on corneal endothelium, Figure 1c) should be performed in each case to properly evaluate and treat the patient. The cornea may also be cloudy due to the acute rise in IOP in angle closure glaucoma.

A corneal abrasion will often cause severe eye pain, photophobia, and tearing. Patients will usually endorse a history of trauma to the affected eye. A drop of proparacaine at time of evaluation will nearly, if not completely, treat the pain. This sensitivity to topical anesthesia is not a feature of a uveitis of any type. Examination with fluorescein will identify the abrasion as a brightly staining lesion of the cornea and unless infected, will not likely have a stromal infiltrate/whitening.

A panuveitis such as seen in acute retinal necrosis from herpes infections and endophthalmitis causes severe inflammation resulting in a red, painful eye. A hypopyn may be found in the anterior chamber (Figure 1e). As discussed elsewhere, this finding should raise alarm. A dilated eye exam is required to identify retinal whitening seen in acute retinal necrosis and significant vitritis in endophthalmitis, and as such, likely require an ophthalmology consultation. If these diagnoses are suspected, an emergent ophthalmology consult should be placed as both are ophthalmic emergencies with earlier treatment resulting in better outcomes.

Most common causes of a red, painful eye:

- Anterior uveitis

- Keratitis

- Corneal abrasion

- Acute angle closure glaucoma

- Conjunctivitis

- Scleritis

Prognosis

In most cases, the prognosis of uveitis is good assuming early detection and proper treatment. While a majority of patients will develop an ocular complication, appropriate treatment and surgery, if needed, make permanent vision loss much less likely.[15]. Identifying the underlying cause of uveitis is also important due to significant morbidity and mortality associated with some specific systemic diseases that can cause uveitis.

Complications

It is crucial to solidify an accurate diagnosis before starting treatment and establish a follow-up plan. Topical corticosteroids are the standard treatment for anterior uveitis; however, they can increase intraocular pressure (IOP). Consequently, the patient must have ophthalmology follow up to monitor for resolution and to monitor IOP. Prolonged or undertreated intraocular inflammation can lead to pathological changes in the eye resulting in permanent vision loss. These complications include cataracts, posterior synechiae, epiretinal membrane (ERM), cystoid macular edema (CME), band keratopathy, hypotony, glaucoma, and optic nerve edema.[15] While anterior chamber inflammation can be treated with topical steroids, other forms of inflammation should never be treated with intraocular, periocular, or oral steroids unless infectious etiologies have been ruled out by detailed examination and laboratory evaluation due to the risk of worsening disease and visual prognosis. Intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis should be referred to ophthalmologists, preferably uveitis specialists when possible, for further evaluation and treatment.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is essential to give the patient education regarding the disease process and emphasize the importance of being compliant with treatment and follow up. The patient should receive counsel on possible complications, which could include complete vision loss. The patient should receive strict return precautions with signs and symptoms that are cause for alarm such as worsening pain, vision, floaters, and/or photophobia.

Pearls and Other Issues

Uveitis can be a vision-threatening disease. A detailed history, exam, and likely laboratory evaluation are required to make an accurate diagnosis. If there is any suspicion for uveitis, urgent ophthalmology referral/consultation is imperative. Immediate treatment should include corticosteroids and cycloplegics for anterior uveitis. Other types of steroids (i.e. oral, periocular, or intraocular) should never be administered until infectious etiologies have been effectively ruled out. The patient will need to be followed for repeat ocular examinations and measurement of IOP.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Uveitis is a condition that can present in emergency departments or primary care settings. It is important to recognize symptoms and make an accurate diagnosis. It is vital for primary care providers to refer the patient to an ophthalmologist if uveitis is suspected. If a patient presents to a facility with symptoms that are consistent with uveitis, and the facility does not have the capabilities to evaluate the complaint properly (i.e., slit lamp expertise and tonometer); the patient should be transferred to a facility that is capable of such exams.

Initiating treatment with topical corticosteroids and cycloplegics is important once the diagnosis of uveitis is made. Because this can be a vision-threatening disease, providers should ensure that patients can afford the prescribed treatments before discharge. If the patient is unable to afford medications, social services can provide patient assistance. Uveitis accounts for approximately 10% of blindness in the United States, thus appropriate treatment and follow up is essential.

Treatment for uveitis should be handled by an interprofessional team approach that includes ophthalmologists, retina and uveitis specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating to support the patient's treatment regimen and bring about the best possible outcome. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Important findings in differentiating a red, painful eye: (a) Ciliary flush, (b) chemosis (red arrow), (c) keratic precipitates (red arrow), (d) posterior synechiae (red arrows), (e) hypopyn (red arrow), (f) ring infiltrate (red arrow), and (g) fluorescein staining of ulcer found in (f). Contributed by Prof. Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS & Dr. Christopher Conrady MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. American journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Sep:140(3):509-16 [PubMed PMID: 16196117]

Harthan JS, Opitz DL, Fromstein SR, Morettin CE. Diagnosis and treatment of anterior uveitis: optometric management. Clinical optometry. 2016:8():23-35. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S72079. Epub 2016 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 30214346]

Yeh S, Forooghian F, Suhler EB. Implications of the Pacific Ocular Inflammation uveitis epidemiology study. JAMA. 2014 May 14:311(18):1912-3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2294. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24825646]

Jakob E, Reuland MS, Mackensen F, Harsch N, Fleckenstein M, Lorenz HM, Max R, Becker MD. Uveitis subtypes in a german interdisciplinary uveitis center--analysis of 1916 patients. The Journal of rheumatology. 2009 Jan:36(1):127-36. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080102. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19132784]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Groot-Mijnes JD, de Visser L, Zuurveen S, Martinus RA, Völker R, ten Dam-van Loon NH, de Boer JH, Postma G, de Groot RJ, van Loon AM, Rothova A. Identification of new pathogens in the intraocular fluid of patients with uveitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Nov:150(5):628-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.015. Epub 2010 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 20691420]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceConrady CD, Hanson KE, Mehra S, Carey A, Larochelle M, Shakoor A. The First Case of Trypanosoma cruzi-Associated Retinitis in an Immunocompromised Host Diagnosed With Pan-Organism Polymerase Chain Reaction. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018 Jun 18:67(1):141-143. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy058. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29385482]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChan AY, Conrady CD, Ding K, Dvorak JD, Stone DU. Factors associated with age of onset of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Cornea. 2015 May:34(5):535-40. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000362. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25710509]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAcharya NR, Tham VM, Esterberg E, Borkar DS, Parker JV, Vinoya AC, Uchida A. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis: results from the Pacific Ocular Inflammation Study. JAMA ophthalmology. 2013 Nov:131(11):1405-12. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24008391]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWildner G, Diedrichs-Möhring M. Autoimmune uveitis induced by molecular mimicry of peptides from rotavirus, bovine casein and retinal S-antigen. European journal of immunology. 2003 Sep:33(9):2577-87 [PubMed PMID: 12938234]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceConrady CD, Feistmann JA, Roller AB, Boldt HC, Shakoor A. HEMORRHAGIC VASCULITIS AND RETINOPATHY HERALDING AS AN EARLY SIGN OF BACTERIAL ENDOPHTHALMITIS AFTER INTRAVITREAL INJECTION. Retinal cases & brief reports. 2019 Fall:13(4):329-332. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000601. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28594738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFraunfelder FW, Rosenbaum JT. Drug-induced uveitis. Incidence, prevention and treatment. Drug safety. 1997 Sep:17(3):197-207 [PubMed PMID: 9306054]

Harman LE, Margo CE, Roetzheim RG. Uveitis: the collaborative diagnostic evaluation. American family physician. 2014 Nov 15:90(10):711-6 [PubMed PMID: 25403035]

Conrady CD, Larochelle M, Pecen P, Palestine A, Shakoor A, Singh A. Checkpoint inhibitor-induced uveitis: a case series. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2018 Jan:256(1):187-191. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3835-2. Epub 2017 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 29080102]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLeibowitz HM. The red eye. The New England journal of medicine. 2000 Aug 3:343(5):345-51 [PubMed PMID: 10922425]

Groen F, Ramdas W, de Hoog J, Vingerling JR, Rothova A. Visual outcomes and ocular morbidity of patients with uveitis referred to a tertiary center during first year of follow-up. Eye (London, England). 2016 Mar:30(3):473-80. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.269. Epub 2016 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 26742865]