Introduction

Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe gastroenteritis in children younger than 5 years of age. In 1973, rotavirus was discovered from duodenal biopsies and fecal samples taken from humans with acute diarrhea. Despite the availability of a vaccine against rotavirus, it continues to result in more than 200,000 deaths worldwide per year. In developed countries with routine vaccination programs, rotavirus infection is less prevalent than in non-developed countries, where it continues to be a major cause of life-threatening diarrhea in infants and children younger than 5. Rotavirus symptoms include profuse diarrhea, vomiting, fever, malaise, and rarely neurologic features such as convulsions, encephalitis, or encephalopathy. The most common symptoms are diarrhea and vomiting, leading to significant dehydration and reduced oral intake, which can necessitate hospitalization and lead to death if not treated.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

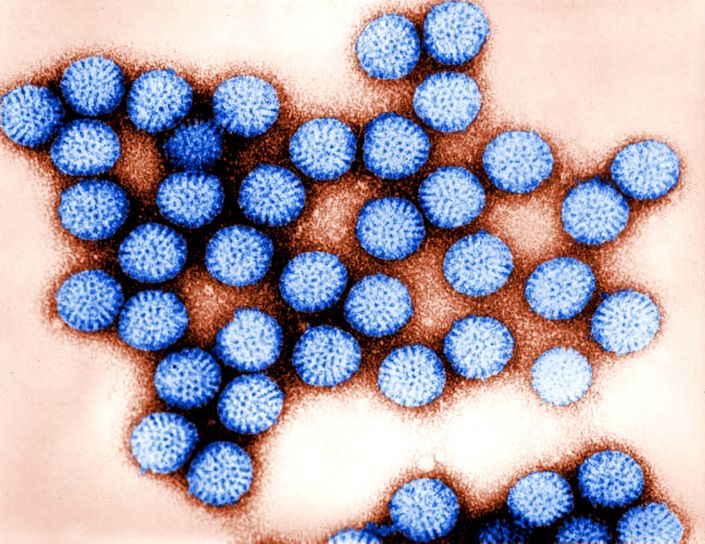

Rotavirus is a double-stranded ribonucleic acid virus, named for its classic “wheel-shaped” appearance on electron microscopy (see Image. Rotavirus).[1] Transmission of rotavirus primarily occurs through the fecal-oral route. Additionally, the viral spread can occur through contaminated hands, fomites, and, rarely, food and water.[3] Prior to the routine use of the rotavirus vaccines, the rates of rotavirus illness among children in low-income countries were similar to those of high-income countries.[2] Since the advent of rotavirus vaccines, norovirus has exceeded rotavirus as the leading cause of acute viral gastroenteritis in high-income countries. In low-income countries and globally, rotavirus infections are the number one cause of acute viral gastroenteritis in children.

Epidemiology

Rotaviruses are found throughout the world, and most children are infected by 5 years of age. The frequency of infection is similar throughout the world; however, fatal infection is more likely in low-income regions throughout the globe. This is likely secondary to the lack of adequate healthcare facilities, increased rates of malnutrition, and lack of access to clean, sanitary hydration therapies.[1] Rotavirus is traditionally thought of as a winter disease, especially in more temperate areas of the globe.[4] In tropical climates, the seasonal trend is less evident, and infections tend to occur year-round. Some research has shown that the frequency of rotavirus infection in temperate climates may also be related to precipitation levels. One study out of Washington, DC revealed that there was a 45% increase in rotavirus hospitalizations following months with low precipitation compared to months with higher levels of precipitation. This indicates that rotavirus transmission is more common in conditions of low humidity, as seen in winter and dry months throughout the year.[5]

Ten different species of rotavirus are currently classified (A-J). Species A rotaviruses are the most common cause of childhood infections, with species B and C also causing a smaller but significant percentage of infections across the world.[2][3] Geographical variances in the strains of species A rotaviruses have been seen circulating globally.[1] Rotavirus disease epidemiology has drastically changed since the development of vaccines against the virus. Prior to vaccine development, rotavirus infection was most common in children younger than 5. Following widespread vaccination programs, rotavirus appears to be more prevalent in older, unvaccinated children. In low-income countries where rotavirus vaccines are not widespread, the prevalence of rotavirus infections appears to be stable. Malnutrition in these regions tends to increase the severity of disease.[6]

Pathophysiology

Rotaviruses replicate in mature enterocytes throughout the small intestinal lumen. This alteration in the epithelial cells of the small intestine leads to an osmotically active food bolus being moved into the large intestine, which subsequently leads to impaired water reabsorption in the large intestine. Impaired water reabsorption, in turn, causes the typical watery diarrhea seen in rotavirus infections. Another possible cause of rotavirus induced diarrhea includes increased intestinal motility, although the cause of this is unclear.[7]

History and Physical

Rotavirus has an incubation period varying from 1 to 3 days, after which symptoms appear abruptly with varying presentations. Symptoms congruent with infection are almost identical to other gastrointestinal infections; however, rotavirus infections tend to be more severe. Fever, diarrhea, and vomiting are the most common presenting symptoms. There is variability seen amongst infected patients, ranging from short-term, mild diarrhea to severe diarrhea with fever and vomiting. Symptoms are most severe in patients whose first infection occurs after 3 months of age. Infants most commonly present with mild symptoms and have a lower likelihood of severe infection. Some infants, however, have been found to present with necrotizing enterocolitis.[8]

In rotavirus infection, vomiting often occurs initially, followed by watery diarrhea. Fever is found in approximately 33% of infected patients.[9] Illness duration is anywhere from 5 to 7 days from onset to full resolution of symptoms. Physical exam findings, typically, do not clearly differentiate rotavirus from other pathogens known to infect the gastrointestinal tract commonly. Exam findings that may be present in individuals with rotavirus infection include fever, abdominal cramping, fatigue, and signs of dehydration such as dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, tachycardia, diminished urine output, and prolonged capillary refill.[10]

Evaluation

Rotavirus is clinically indistinguishable from diarrheal diseases caused by other gastrointestinal pathogens such as noroviruses, enteric adenoviruses, astroviruses, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella. In most cases, no additional evaluation is necessary beyond history and physical exam. Findings that suggest rotavirus infection include a mild fever in conjunction with vomiting and watery diarrhea. Fever, presence of an acid-reducing substance in the stool, and low serum bicarbonate levels are more likely in rotavirus-induced gastroenteritis. Gross bloody diarrhea likely indicates an alternate organism as the cause of acute gastroenteritis.[1]

Lab testing is generally not performed, but it is the only way to confirm the diagnosis of rotavirus. In severe, intractable cases of infection, a confirmatory lab test may be indicated to solidify the diagnosis of rotavirus.[3] When a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis is desired, a rotavirus antigen can be found in stool samples using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or immunochromatography. The addition of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays is more sensitive and allows genotyping of virus isolates and as such, may be indicated in epidemiological studies.[1] Additional methods of detection include electron microscopy, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, antigen detection assays, and virus isolation.[3] In most cases, confirmation testing is only indicated if it could potentially cut costs by decreasing hospital stays or avoiding unnecessary procedures.[11]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of rotavirus infection is directed at the relief of symptoms and the treatment and prevention of associated dehydration.[3] Oral rehydration salt solutions should initially be attempted. In adults, codeine, loperamide, and diphenoxylate can be added to help with symptom relief and to control the volume of diarrhea. Bismuth salicylate has also been proven to be beneficial in the treatment of rotavirus symptoms but should only be considered when other infectious agents have been ruled out.[11] If symptoms are refractory to oral therapies and the patient is dehydrated, admission to the hospital and intravenous fluids may be required.

In a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Guarino and colleagues tested the antiretroviral effects of orally administered human serum immunoglobulins. Ninety-eight children admitted with acute gastroenteritis were separated into a treatment and control group. Children in the treatment group received a single dose of 300 mg/kg bodyweight of human serum immunoglobulin. The results of this study showed that children who received human immunoglobulin had a statistically significant improvement in clinical condition and stool patterns when compared to the control group. The total duration of rotaviral-induced diarrhea was found to be 76 hours in the treatment group compared to 131 hours in the control group. Viral excretion and hospital stay duration were also significantly reduced in the treatment group. These findings suggest that oral administration of human serum immunoglobulins may be beneficial in the treatment of hospitalized children with rotavirus disease.[12] Additional studies indicate that treatments such as probiotics, zinc, and ondansetron may also be effective in the treatment of acute gastroenteritis.[3] Most patients presenting to an outpatient clinic or the emergency department can be discharged home safely. Adults may benefit from antiemetic medications, but these should be avoided in young children. Hospital admission may be beneficial to patients with signs or symptoms of dehydration, intractable vomiting, electrolyte disturbances, abdominal pain, ileus, renal failure, or pregnancy.[13] (A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for rotavirus-induced acute gastroenteritis is broad and includes a variety of viral, bacterial, and parasitic pathogens, as well as acute abdominal pathology.[14][13] Viral infections that are known to cause acute viral gastroenteritis similar to that of rotavirus include norovirus, adenovirus, and astroviruses. Of the viral causes of acute gastroenteritis, norovirus has become the most common cause of viral gastroenteritis since the advent of the rotavirus vaccine.[13] Viral infections are known to be the most common cause of acute infectious diarrhea, with less than 5% of stool cultures being positive for non-viral pathogens.

Common bacterial causes of gastroenteritis include infections with Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escheri coli, Yersinia, Vibrio, Listeria, and Clostridium difficile. Bacterial causes should be ruled out, especially in severe cases of infectious diarrhea, as bacteria are known to cause a more severe form of gastroenteritis than seen with other etiologies. Stool testing for bacterial pathogens is warranted in patients who present with severe symptoms such as dehydration, hypovolemia, and severe abdominal pain or those patients who require hospitalization. Additionally, pregnant women, adults older than 70, and patients with immunocompromised states should have stool cultures performed to rule out bacterial causes of infection.[15]

Various parasitic infections can lead to acute gastroenteritis, including Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Mycobacterium. In cases where parasitic causes are suspected, stool samples should be tested for ova and parasites, and appropriate antimicrobial treatment should be initiated if tests are positive.[14] In patients with acute diarrhea, abdominal pathology should always be ruled out. Acute appendicitis, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, bowel obstruction, irritable bowel syndrome, ischemic bowel disease, laxative abuse, diabetes, malabsorption syndromes, scleroderma, and celiac sprue can all present with symptoms similar to that of rotavirus infection. When the diagnostic evaluation has failed to yield a cause for acute diarrhea, noninfectious extraintestinal causes should be considered.[14]

Prognosis

Rotavirus symptoms are typically isolated to the gastrointestinal tract; however, infections can become systemic and lead to extra-intestinal manifestations such as meningitis, encephalitis, and seizures. Children are more likely to present with fever, dehydration, and metabolic acidosis when compared to other pathogenic causes of viral gastroenteritis. Results from one study by Karampatsas and colleagues out of the United Kingdom reported that seizures and mild neurologic signs are surprisingly common in rotavirus infections. In this study, encephalitis was only associated with rotavirus-positive gastroenteritis. The mechanism of action leading to neurologic sequelae is unclear. Rotavirus RNA is present in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients with central nervous system symptoms, which may indicate a direct viral invasion. Rotavirus may lead to alterations in calcium homeostasis. Altered calcium homeostasis may induce seizures or lead to an increased susceptibility to seizure activity. A clear association between alterations in calcium homeostasis and seizure activity has not yet been found.[16]

Complications

Approximately 500,000 children younger than 5 die annually secondary to diarrhea, with rotavirus as the leading cause. It is estimated that 200,000 people die annually secondary to rotavirus infection. Severe dehydration is responsible for death in rotavirus infections. Additional complications, including neurologic sequelae, typically resolve with the treatment of rotavirus infection.[17]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Several vaccines have been developed for the prevention of rotavirus over the years. Most of the vaccines are live-attenuated variants of naturally occurring strains. An early vaccine for rotavirus was removed from the market due to an increased risk of intussusception. A newer vaccine is a monovalent human vaccine given in two doses from 6 to 24 weeks. A pentavalent bovine-human reassortant vaccine is also available. It is given in 3 doses from 6 to 32 weeks. Analysis of both newer vaccines shows decreased vaccine efficacy in patients from high-mortality regions when compared to low-mortality regions. Both vaccines are considered safe and have no significant increase in adverse events between vaccine and placebo groups. China, India, and Vietnam have vaccines that are licensed locally, and additional vaccines are being evaluated in clinical trials across the world.

All of the currently available vaccines for rotavirus infection are live attenuated vaccines. These are not without risk, as evidenced by the increased risk of intussusception with the first vaccine's administration. Since the removal of the earliest vaccine from the market, various studies have been performed to evaluate the factors that lead to an increased risk of intussusception. The incidence of intussusception is increased 3 to 14 days after vaccine administration, particularly following the first dose of the vaccine. Additional studies showed that the administration of the vaccine in infants greater than 90 days old led to over 80% of cases of intussusception. Studies that evaluate the risk of the currently available vaccines in various age groups are ongoing. Overall, the benefit of rotavirus vaccination clearly outweighs the risks of adverse events, including intussusception. To further decrease the risk of intussusception, vaccination should be given to individuals in two doses and less than 60 days of age.[17]

Pearls and Other Issues

Rotavirus infections are significantly more lethal in low-income countries when compared with high-income countries. Additionally, the efficacy of vaccines is decreased in low-income countries when compared to high-income countries. Factors such as climate, poverty, poor nutrition, inadequate sanitation, and prevalence of diseases are known to decrease the efficacy of vaccines. Further studies are necessary to determine what alterations can be made to vaccine delivery systems and to better address the vaccination need in low-income areas worldwide.

On a global scale, there are significant disparities in healthcare outcomes between low-income and high-income countries due to the lack of clean water, the absence of resources to maintain adequate hygiene and sanitization, poor education, and the absence of healthcare facilities and vaccine programs. Many low-income countries lack the necessary resources to prevent disease outbreaks, and rotavirus vaccines are not as readily available in these regions. Most rotavirus vaccines are stable only in climate-controlled environments, making it difficult to distribute to temperate regions of the globe where the mortality rate is the highest.

To combat rotavirus mortality on a global scale, it is necessary to invest in research and vaccine development that targets the specific needs of every population impacted by this infection. This includes the low-income countries where healthcare resources and funding are lacking. Every attempt should be made to ensure that these regions of the globe have access to adequate nutrition, clean water, necessary hygiene products, and appropriate healthcare facilities to combat the illness. Only when these advancements are made will we see a truly significant decrease in global mortality from rotavirus infections.[17]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to the broad differential diagnosis for acute gastroenteritis, accurate diagnosis of rotavirus infection requires strong interprofessional communication between the patient, family, nurses, emergency room physicians, primary care physicians, infectious disease physicians, and pediatricians. Transmission of rotavirus occurs primarily through the fecal-oral route and is frequently passed between individuals in daycare or household settings. Once an accurate diagnosis is made, the whole interprofessional team must educate the patient and the family on the importance of handwashing and disinfection techniques to prevent the transmission cycle of the virus. Patients should be advised to quarantine and stay home from school until complete symptom resolution.

In patients who require inpatient admission, communication between all members of the healthcare team is critical. Oral and intravenous fluid intake should be closely monitored by the nursing staff and communicated effectively to physicians to ensure the patient is maintaining adequate hydration. Dietary consults may be beneficial to optimize treatment and prevent electrolyte and nutritional deficiencies that may result from the illness. Any cases of emesis or diarrhea should be communicated as well to track the progression of the illness. Educating the patient and family members on all aspects of the illness, including transmission, prevention, and treatment, is critical. Nurses, physicians, dieticians, and additional members of the interprofessional team should take every available opportunity to educate patients and family members.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Crawford SE, Ramani S, Tate JE, Parashar UD, Svensson L, Hagbom M, Franco MA, Greenberg HB, O'Ryan M, Kang G, Desselberger U, Estes MK. Rotavirus infection. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2017 Nov 9:3():17083. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.83. Epub 2017 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 29119972]

Dennehy PH. Rotavirus vaccines: an overview. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2008 Jan:21(1):198-208. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-07. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18202442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParashar UD, Nelson EA, Kang G. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2013 Dec 30:347():f7204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7204. Epub 2013 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 24379214]

Cook SM, Glass RI, LeBaron CW, Ho MS. Global seasonality of rotavirus infections. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1990:68(2):171-7 [PubMed PMID: 1694734]

Brandt CD, Kim HW, Rodriguez WJ, Arrobio JO, Jeffries BC, Parrott RH. Rotavirus gastroenteritis and weather. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1982 Sep:16(3):478-82 [PubMed PMID: 7130360]

Markkula J, Hemming-Harlo M, Salminen MT, Savolainen-Kopra C, Pirhonen J, Al-Hello H, Vesikari T. Rotavirus epidemiology 5-6 years after universal rotavirus vaccination: persistent rotavirus activity in older children and elderly. Infectious diseases (London, England). 2017 May:49(5):388-395. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2016.1275773. Epub 2017 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 28067093]

Greenberg HB, Estes MK. Rotaviruses: from pathogenesis to vaccination. Gastroenterology. 2009 May:136(6):1939-51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.076. Epub 2009 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 19457420]

Bernstein DI. Rotavirus overview. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2009 Mar:28(3 Suppl):S50-3. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967bee. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19252423]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChiejina M, Samant H. Viral Diarrhea. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262044]

Hoxha T, Xhelili L, Azemi M, Avdiu M, Ismaili-Jaha V, Efendija-Beqa U, Grajcevci-Uka V. Performance of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children with acute gastroenteritis. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2015 Feb:69(1):10-2. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2015.69.10-12. Epub 2015 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 25870468]

Anderson EJ, Weber SG. Rotavirus infection in adults. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2004 Feb:4(2):91-9 [PubMed PMID: 14871633]

Guarino A, Canani RB, Russo S, Albano F, Canani MB, Ruggeri FM, Donelli G, Rubino A. Oral immunoglobulins for treatment of acute rotaviral gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 1994 Jan:93(1):12-6 [PubMed PMID: 8265305]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStuempfig ND, Seroy J. Viral Gastroenteritis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085537]

Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Slutsker L, Tauxe RV, Hennessy T, Griffin PM, DuPont H, Sack RB, Tarr P, Neill M, Nachamkin I, Reller LB, Osterholm MT, Bennish ML, Pickering LK, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001 Feb 1:32(3):331-51 [PubMed PMID: 11170940]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSattar SBA, Singh S. Bacterial Gastroenteritis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020667]

Karampatsas K,Osborne L,Seah ML,Tong CYW,Prendergast AJ, Clinical characteristics and complications of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children in east London: A retrospective case-control study. PloS one. 2018; [PubMed PMID: 29565992]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCarvalho MF, Gill D. Rotavirus vaccine efficacy: current status and areas for improvement. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2019:15(6):1237-1250. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1520583. Epub 2018 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 30215578]