Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI), colloquially known as “heart attack,” is caused by decreased or complete cessation of blood flow to a portion of the myocardium. Myocardial infarction may be “silent” and go undetected, or it could be a catastrophic event leading to hemodynamic deterioration and sudden death.[1] Most myocardial infarctions are due to underlying coronary artery disease, the leading cause of death in the United States. With coronary artery occlusion, the myocardium is deprived of oxygen. Prolonged deprivation of oxygen supply to the myocardium can lead to myocardial cell death and necrosis.[2] Patients can present with chest discomfort or pressure that can radiate to the neck, jaw, shoulder, or arm. In addition to the history and physical exam, myocardial ischemia may be associated with ECG changes and elevated biochemical markers such as cardiac troponins.[3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

As stated above, myocardial infarction is closely associated with coronary artery disease. INTERHEART is an international multi-center case-control study which delineated the following modifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease:[5][6]

- Smoking

- Abnormal lipid profile/blood apolipoprotein (raised ApoB/ApoA1)

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Abdominal obesity (waist/hip ratio) (greater than 0.90 for males and greater than 0.85 for females)

- Psychosocial factors such as depression, loss of the locus of control, global stress, financial stress, and life events including marital separation, job loss, and family conflicts

- Lack of daily consumption of fruits or vegetables

- Lack of physical activity

- Alcohol consumption (weaker association, protective)

The INTERHEART study showed that all the above risk factors were significantly associated with acute myocardial infarction except for alcohol consumption, which showed a weaker association. Smoking and abnormal apolipoprotein ratio showed the strongest association with acute myocardial infarction. The increased risk associated with diabetes and hypertension were found to be higher in women, and the protective effect of exercise and alcohol was also found to be higher in women.[5]

Other risk factors include a moderately high level of plasma homocysteine, which is an independent risk factor of MI. Elevated plasma homocysteine is potentially modifiable and can be treated with folic acid, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12.[7]

Some non-modifiable risk factors for myocardial infarction include advanced age, male gender (males tend to have myocardial infarction earlier in life), genetics (there is an increased risk of MI if a first-degree relative has a history of cardiovascular events before the age of 50).[6][8] The role of genetic loci that increase the risk for MI is under active investigation.[9][10]

Epidemiology

The most common cause of death and disability in the western world and worldwide is coronary artery disease.[11] Based on 2015 mortality data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS-CDC), MI mortality was 114,023, and MI any-mention mortality (i.e., MI is mentioned as a contributing factor in the death certificate) was 151,863.

As per the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)-CDC data from 2011 to 2014, an estimated 16.5 million Americans older than 20 years of age have coronary artery disease, and the prevalence was higher in males than females for all ages. As per the NHANES 2011 through 2014, the overall prevalence of MI is 3.0% in US adults older than 20 years of age.

Prevalence of MI in the US Sub-populations

Non-Hispanic Whites

- 4.0% (Male)

- 2.4% (Female)

Non-Hispanic Blacks

- 3.3% (Male)

- 2.2% (Female)

Hispanics

- 2.9% (Male)

- 2.1% (Female)

Non-Hispanic Asians

- 2.6% (Male)

- 0.7% (Female)

Based on the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) performed by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) collected between 2005 and 2014, the estimated annual incidence is 605,000 new MIs and 200,000 recurrent MIs.[12]

The ARIC study also found that the average age at first MI is 65.6 years for males and 72.0 years for females. In the past decades, several studies have shown a declining incidence of MI in the United States.[12]

Pathophysiology

The acute occlusion of one or multiple large epicardial coronary arteries for more than 20 to 40 minutes can lead to acute myocardial infarction. The occlusion is usually thrombotic and due to the rupture of a plaque formed in the coronary arteries. The occlusion leads to a lack of oxygen in the myocardium, which results in sarcolemmal disruption and myofibril relaxation.[2] These changes are one of the first ultrastructural changes in the process of MI, which are followed by mitochondrial alterations. The prolonged ischemia ultimately results in liquefactive necrosis of myocardial tissue. The necrosis spreads from sub-endocardium to sub-epicardium. The subepicardium is believed to have increased collateral circulation, which delays its death.[2] Depending on the territory affected by the infarction, the cardiac function is compromised. Due to the negligible regeneration capacity of the myocardium, the infarcted area heals by scar formation, and often, the heart is remodeled characterized by dilation, segmental hypertrophy of remaining viable tissue, and cardiac dysfunction.[13]

History and Physical

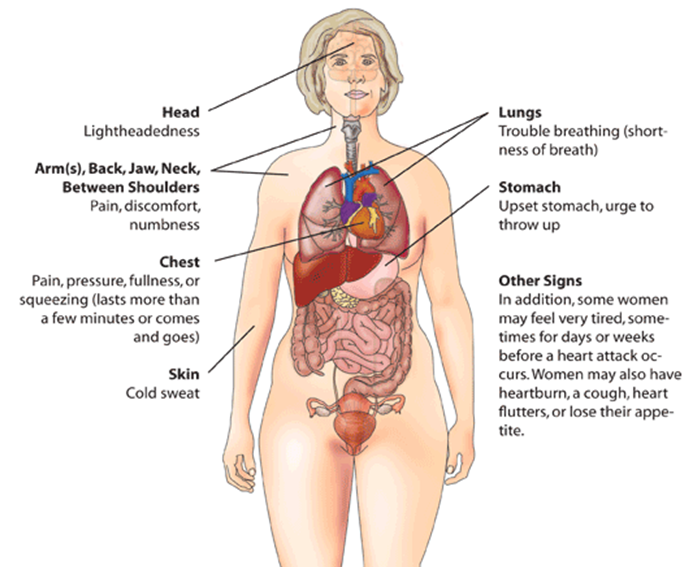

The imbalance between oxygen supply and the demand leads to myocardial ischemia and can sometimes lead to myocardial infarction. The patient’s history, electrocardiographic findings, and elevated serum biomarkers help identify ischemic symptoms. Myocardial ischemia can present as chest pain, upper extremity pain, mandibular, or epigastric discomfort that occurs during exertion or at rest. Myocardial ischemia can also present as dyspnea or fatigue, which are known to be ischemic equivalents.[14] The chest pain is usually retrosternal and is sometimes described as the sensation of pressure or heaviness. The pain often radiates to the left shoulder, neck, or arms with no obvious precipitating factors, and it may be intermittent or persistent. The pain usually lasts for more than 20 minutes.[15] It is usually not affected by positional changes or active movement of the region. Additional symptoms, such as sweating, nausea, abdominal pain, dyspnea, and syncope, may also be present.[14][16][17] The MI can also present atypically with subtle findings such as palpitations, or more dramatic manifestations, such as cardiac arrest. The MI can sometimes present with no symptoms.[18]

Evaluation

The three components in the evaluation of the MI are clinical features, ECG findings, and cardiac biomarkers.

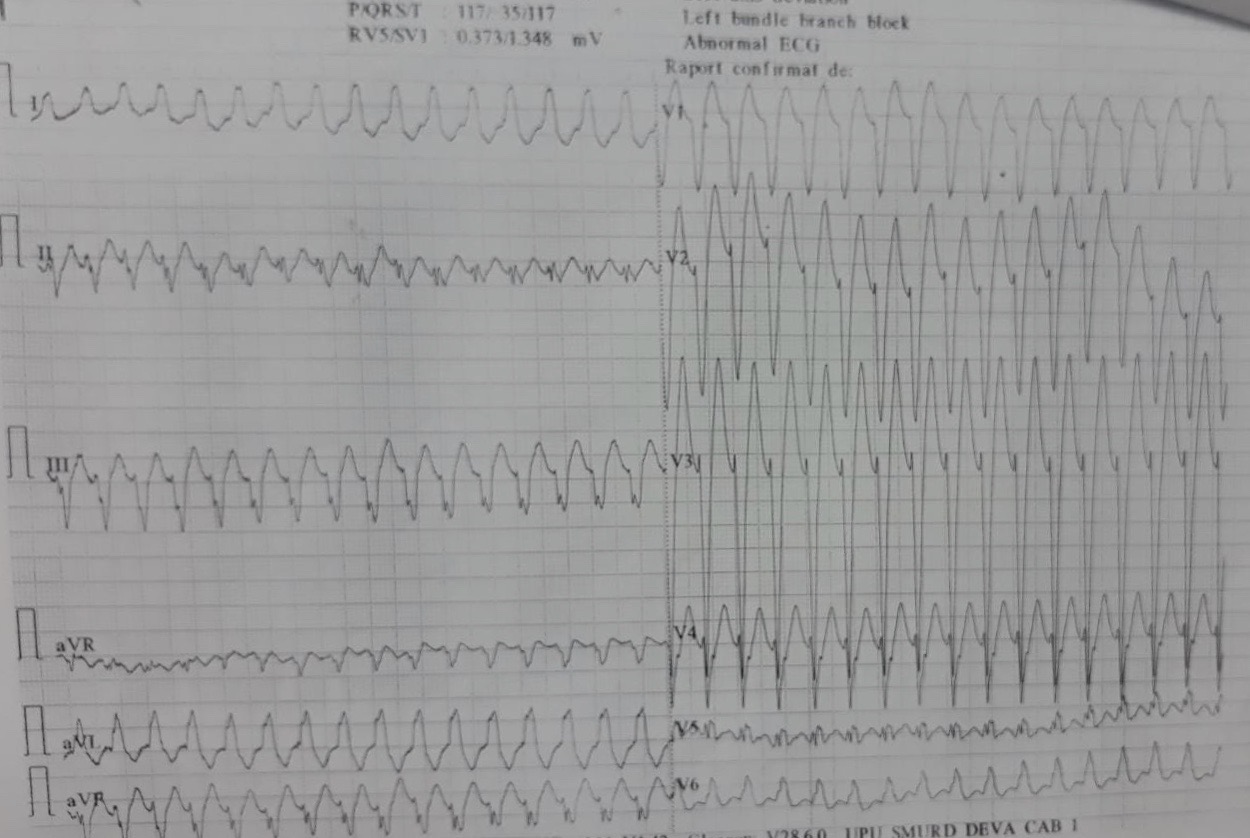

ECG

The resting 12 lead ECG is the first-line diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). It should be obtained within 10 minutes of the patient’s arrival in the emergency department.[17] Acute MI is often associated with dynamic changes in the ECG waveform. Serial ECG monitoring can provide important clues to the diagnosis if the initial EKG is non-diagnostic at initial presentation.[14] Serial or continuous ECG recordings may help determine reperfusion or re-occlusion status. A large and prompt reduction in ST-segment elevation is usually seen in reperfusion.[14]

ECG findings suggestive of ongoing coronary artery occlusion (in the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and bundle branch block):[19]

ST-segment elevation in two contiguous lead (measured at J-point) of

- Greater than 5 mm in men younger than 40 years, greater than 2 mm in men older than 40 years, or greater than 1.5 mm in women in leads V2-V3 and/or

- Greater than 1 mm in all other leads

ST-segment depression and T-wave changes

- New horizontal or down-sloping ST-segment depression greater than 5 mm in 2 contiguous leads and/or T inversion greater than 1 mm in two contiguous leads with prominent R waves or R/S ratio of greater than 1

The hyperacute T-wave amplitude, with prominent symmetrical T waves in two contiguous leads, maybe an early sign of acute MI that may precede the ST-segment elevation. Other ECG findings associated with myocardial ischemia include cardiac arrhythmias, intraventricular blocks, atrioventricular conduction delays, and loss of precordial R-wave amplitude (less specific finding).[14]

ECG findings alone are not sufficient to diagnose acute myocardial ischemia or acute MI as other conditions such as acute pericarditis, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), left bundle branch block (LBBB), Brugada syndrome, Takatsubo syndrome (TTS), and early repolarization patterns also present with ST deviation.

ECG changes associated with prior MI (in the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle branch block):

- Any Q wave in lead V2-V3 greater than 0.02 s or QS complex in leads V2-V3

- Q wave > 03 s and greater than 1 mm deep or QS complex in leads I, II, aVL, aVF or V4-V6 in any two leads of contiguous lead grouping (I, aVL; V1-V6; II, III, aVF)

- R wave > 0.04 s in V1-V2 and R/S greater than 1 with a concordant positive T wave in the absence of conduction defect.

Biomarker Detection of MI

Cardiac troponins (I and T) are components of the contractile apparatus of myocardial cells and expressed almost exclusively in the heart. Elevated serum levels of cardiac troponin are not specific to the underlying mode of injury (ischemic vs. tension)[14] [20]. The rising and/or falling pattern of cardiac troponins (cTn) values with at least one value above the 99 percentile of upper reference limit (URL) associated with symptoms of myocardial ischemia would indicate an acute MI. Serial testing of cTn values at 0 hours, 3 hours, and 6 hours would give a better perspective on the severity and time course of the myocardial injury. Depending on the baseline cTn value, the rising/falling pattern is interpreted. If the cTn baseline value is markedly elevated, a minimum change of greater than 20% in follow up testing is significant for myocardial ischemia. Creatine kinase MB isoform can also be used in the diagnosis of MI, but it is less sensitive and specific than cTn level.[4][21]

Imaging

Different imaging techniques are used to assess myocardial perfusion, myocardial viability, myocardial thickness, thickening and motion, and the effect of myocyte loss on the kinetics of para-magnetic or radio-opaque contrast agents indicating myocardial fibrosis or scars.[14] Some imaging modalities that can be used are echocardiography, radionuclide imaging, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cardiac MRI). Regional wall motion abnormalities induced by ischemia can be detected by echocardiography almost immediately after the onset of ischemia when greater than 20% transmural myocardial thickness is affected. Cardiac MRI provides an accurate assessment of myocardial structure and function.[14]

Treatment / Management

Acute Management

Reperfusion therapy is indicated in all patients with symptoms of ischemia of less than 12-hours duration and persistent ST-segment elevation. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is preferred to fibrinolysis if the procedure can be performed <120 minutes of ECG diagnosis. If there is no immediate option of PCI (>120 minutes), fibrinolysis should be started within 10 minutes of STEMI after ruling out contraindications. If transfer to a PCI center is possible in 60 to 90 minutes after a bolus of the fibrinolytic agent and patient meets reperfusion criteria, a routine PCI can be done, or a rescue PCI can be planned.[19][17] If fibrinolysis is planned, it should be carried out with fibrin-specific agents such as tenecteplase, alteplase, or reteplase (class I).[19]

Relief of pain, breathlessness, and anxiety: The chest pain due to myocardial infarction is associated with sympathetic arousal, which causes vasoconstriction and increased workload for the ischemic heart. Intravenous opioids (e.g., morphine) are the analgesics most commonly used for pain relief (Class IIa).[19] The results from CRUSADE quality improvement initiative have shown that the use of morphine may be associated with a higher risk of death and adverse clinical outcomes.[22] The study was done from the CIRCUS (Does Cyclosporine Improve outcome in STEMI patients) database, which showed no significant adverse events associated with morphine use in a case of anterior ST-segment elevation MI.[23] A mild anxiolytic (usually a benzodiazepine) may be considered in very anxious patients (class IIa). Supplemental oxygen is indicated in patients with hypoxemia (SaO2 <90% or PaO2 <60mm Hg) (Class I).[19](B2)

Nitrates: Intravenous nitrates are more effective than sublingual nitrates with regard to symptom relief and regression of ST depression (NSTEMI). The dose is titrated upward until symptoms are relieved, blood pressure is normalized in hypertensive patients, or side effects such as a headache and hypotension are noted.[17]

Beta-blockers: This group of drugs reduces myocardial oxygen consumption by lowering heart rate, blood pressure, and myocardial contractility. They block beta receptors in the body, including the heart, and reduce the effects of circulating catecholamines. Beta-blockers should not be used in suspected coronary vasospasm.

Platelet inhibition: Aspirin is recommended in both STEMI and NSTEMI in an oral loading dose of 150 to 300 mg (non-enteric coated formulation) and a maintenance dose of 75 to 100 mg per day long-term regardless of treatment strategy (class I).[17] Aspirin inhibits thromboxane A2 production throughout the lifespan of the platelet.[24]

Most P2Y12 inhibitors are inactive prodrugs (except for ticagrelor, which is an orally active drug that does not require activation) that require oxidation by hepatic cytochrome P450 system to generate an active metabolite which selectively inhibits P2Y12 receptors irreversibly. Inhibition of P2Y12 receptors leads to inhibition of ATP induced platelet aggregation. The commonly used P2Y12 inhibitors are clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor.

The loading dose for clopidogrel is 300 to 600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg per day.

Prasugrel, 60 mg loading dose, and 10 mg per day of a maintenance dose have a faster onset when compared to clopidogrel.[19]

Patients undergoing PCI should be treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin + P2Y12 inhibitor and a parenteral anticoagulant. In PCI, the use of prasugrel or ticagrelor is found to be superior to clopidogrel. Aspirin and clopidogrel are also found to decrease the number of ischemic events in NSTEMI and UA.[17]

The anticoagulants used during PCI are unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, and bivalirudin. The bivalirudin is recommended during primary PCI if the patient has heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.[19]

Long-Term Management

Lipid-lowering treatment: It is recommended to start high-intensity statins that reduce low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) and stabilize atherosclerotic plaques. High-density lipoproteins are found to be protective.[19]

Antithrombotic therapy: Aspirin is recommended lifelong, and the addition of another agent depends on the therapeutic procedure done, such as PCI with stent placement.

ACE inhibitors are recommended in patients with systolic left ventricular dysfunction, or heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes.

Beta-blockers are recommended in patients with LVEF less than 40% if no other contraindications are present.

Antihypertensive therapy can maintain a blood pressure goal of less than 140/90 mm Hg.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy is recommended in a patient with left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF less than 40%).

Glucose lowering therapy in people with diabetes to achieve current blood sugar goals. [19]

Lifestyle Modifications

Smoking cessation is the most cost-effective secondary measure to prevent MI. Smoking has a pro-thrombotic effect, which has a strong association with atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction.[6](B2)

Diet, alcohol, and weight control: A diet low in saturated fat with a focus on whole grain products, vegetables, fruits, and the fish is considered cardioprotective. The target level for bodyweight is body mass index of 20 to 25 kg/m2 and waist circumference of <94 cm for the men and <80 cm for the female.[25]

Differential Diagnosis

- Angina pectoris

- Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

- ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pneumothorax

Prognosis

Despite many advances in treatment, acute MI still carries a mortality rate of 5-30%; the majority of deaths occur prior to arrival to the hospital. In addition, within the first year after an MI, there is an additional mortality rate of 5% to 12%. The overall prognosis depends on the extent of heart muscle damage and ejection fraction. Patients with preserved left ventricular function tend to have good outcomes. Factors that worsen prognosis include:

- Diabetes

- Advanced age

- Delayed reperfusion

- Low ejection fraction

- Presence of congestive heart failure

- Elevations in C-reactive protein and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels

- Depression

Complications

Type and Manifestation

I: Ischemic

- Reinfarction

- Extension of infarction

- Angina

II: Arrhythmias

- Supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmia

- Sinus bradycardia and atrioventricular block

III: Mechanical

- Myocardial dysfunction

- Cardiac failure

- Cardiogenic shock

- Cardiac rupture (Free wall rupture, ventricular septal rupture, papillary muscle rupture)

IV: Embolic

- Left ventricular mural thrombus,

- Peripheral embolus

V: Inflammatory

- Pericarditis (infarct associated pericarditis, late pericarditis, or post-cardiac injury pericarditis)

- Pericardial effusion

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of patients with ischemic heart disease are best done with an interprofessional team. In most hospitals, there are cardiology teams that are dedicated to the management of these patients.

For patients who present with chest pain, the key to the management of MI is time to treatment. Thus, healthcare professionals, including nurses who work in the emergency department, must be familiar with the symptoms of MI and the importance of rapid triage. A cardiology consult should be made immediately to ensure that the patient gets treated within the time frame recommendations. Because MI can be associated with several serious complications, these patients are best managed in an ICU setting.

There is no cure for ischemic heart disease, and all treatments are symptom-oriented. The key to improving outcomes is to prevent coronary artery disease. The primary care provider and nurse practitioner should educate the patient on the benefits of a healthy diet, the importance of controlling blood pressure and diabetes, exercising regularly, discontinuing smoking, maintaining healthy body weight, and remaining compliant with medications. The pharmacist should educate the patient on types of medication used to treat ischemic heart disease, their benefits, and potential adverse effects.

Only through such a team approach can the morbidity and mortality of myocardial infarction be lowered. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

ECG With Pardee Waves Indicating AMI. Pardee waves indicate acute myocardial infarction in the inferior leads II, III, and aVF with reciprocal changes in the anterolateral leads.

Glenlarson, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Video to Play)

Transesophageal Echocardiography, Pulmonary Embolism. Acute ECG segment elevation mimicking myocardial infarction in a patient with pulmonary embolism.

T Goslar, M Podbregar, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, Katus HA, Newby LK, Ravkilde J, Chaitman B, Clemmensen PM, Dellborg M, Hod H, Porela P, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Beller GA, Bonow R, Van der Wall EE, Bassand JP, Wijns W, Ferguson TB, Steg PG, Uretsky BF, Williams DO, Armstrong PW, Antman EM, Fox KA, Hamm CW, Ohman EM, Simoons ML, Poole-Wilson PA, Gurfinkel EP, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Mendis S, Zhu JR, Wallentin LC, Fernández-Avilés F, Fox KM, Parkhomenko AN, Priori SG, Tendera M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Vahanian A, Camm AJ, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Morais J, Brener S, Harrington R, Morrow D, Lim M, Martinez-Rios MA, Steinhubl S, Levine GN, Gibler WB, Goff D, Tubaro M, Dudek D, Al-Attar N. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007 Nov 27:116(22):2634-53 [PubMed PMID: 17951284]

Reimer KA, Jennings RB, Tatum AH. Pathobiology of acute myocardial ischemia: metabolic, functional and ultrastructural studies. The American journal of cardiology. 1983 Jul 20:52(2):72A-81A [PubMed PMID: 6869259]

Apple FS, Sandoval Y, Jaffe AS, Ordonez-Llanos J, IFCC Task Force on Clinical Applications of Cardiac Bio-Markers. Cardiac Troponin Assays: Guide to Understanding Analytical Characteristics and Their Impact on Clinical Care. Clinical chemistry. 2017 Jan:63(1):73-81. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.255109. Epub 2016 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 28062612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoodman SG, Steg PG, Eagle KA, Fox KA, López-Sendón J, Montalescot G, Budaj A, Kennelly BM, Gore JM, Allegrone J, Granger CB, Gurfinkel EP, GRACE Investigators. The diagnostic and prognostic impact of the redefinition of acute myocardial infarction: lessons from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). American heart journal. 2006 Mar:151(3):654-60 [PubMed PMID: 16504627]

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L, INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet (London, England). 2004 Sep 11-17:364(9438):937-52 [PubMed PMID: 15364185]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAnand SS, Islam S, Rosengren A, Franzosi MG, Steyn K, Yusufali AH, Keltai M, Diaz R, Rangarajan S, Yusuf S, INTERHEART Investigators. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in women and men: insights from the INTERHEART study. European heart journal. 2008 Apr:29(7):932-40. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn018. Epub 2008 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 18334475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStampfer MJ, Malinow MR, Willett WC, Newcomer LM, Upson B, Ullmann D, Tishler PV, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of plasma homocyst(e)ine and risk of myocardial infarction in US physicians. JAMA. 1992 Aug 19:268(7):877-81 [PubMed PMID: 1640615]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNielsen M, Andersson C, Gerds TA, Andersen PK, Jensen TB, Køber L, Gislason G, Torp-Pedersen C. Familial clustering of myocardial infarction in first-degree relatives: a nationwide study. European heart journal. 2013 Apr:34(16):1198-203. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs475. Epub 2013 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 23297314]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSamani NJ, Burton P, Mangino M, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ, Barrett J, Bishop T, Hall A, BHF Family Heart Study Research Group. A genomewide linkage study of 1,933 families affected by premature coronary artery disease: The British Heart Foundation (BHF) Family Heart Study. American journal of human genetics. 2005 Dec:77(6):1011-20 [PubMed PMID: 16380912]

Wang Q, Rao S, Shen GQ, Li L, Moliterno DJ, Newby LK, Rogers WJ, Cannata R, Zirzow E, Elston RC, Topol EJ. Premature myocardial infarction novel susceptibility locus on chromosome 1P34-36 identified by genomewide linkage analysis. American journal of human genetics. 2004 Feb:74(2):262-71 [PubMed PMID: 14732905]

Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, Zheng ZJ, Flegal K, O'Donnell C, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, Goff DC Jr, Hong Y, Adams R, Friday G, Furie K, Gorelick P, Kissela B, Marler J, Meigs J, Roger V, Sidney S, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wilson M, Wolf P, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006 Feb 14:113(6):e85-151 [PubMed PMID: 16407573]

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 Mar 20:137(12):e67-e492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. Epub 2018 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 29386200]

Frangogiannis NG. Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction. Comprehensive Physiology. 2015 Sep 20:5(4):1841-75. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150006. Epub 2015 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 26426469]

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD, Mickley H, Crea F, Van de Werf F, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Katus HA, Pinto FJ, Antman EM, Hamm CW, De Caterina R, Januzzi JL Jr, Apple FS, Alonso Garcia MA, Underwood SR, Canty JM Jr, Lyon AR, Devereaux PJ, Zamorano JL, Lindahl B, Weintraub WS, Newby LK, Virmani R, Vranckx P, Cutlip D, Gibbons RJ, Smith SC, Atar D, Luepker RV, Robertson RM, Bonow RO, Steg PG, O'Gara PT, Fox KAA. [Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018)]. Kardiologia polska. 2018:76(10):1383-1415. doi: 10.5603/KP.2018.0203. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30338834]

Mendis S, Thygesen K, Kuulasmaa K, Giampaoli S, Mähönen M, Ngu Blackett K, Lisheng L, Writing group on behalf of the participating experts of the WHO consultation for revision of WHO definition of myocardial infarction. World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction: 2008-09 revision. International journal of epidemiology. 2011 Feb:40(1):139-46. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq165. Epub 2010 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 20926369]

Malik MA, Alam Khan S, Safdar S, Taseer IU. Chest Pain as a presenting complaint in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2013 Apr:29(2):565-8 [PubMed PMID: 24353577]

Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal. 2016 Jan 14:37(3):267-315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26320110]

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasché P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. European heart journal. 2012 Oct:33(20):2551-67. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184. Epub 2012 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 22922414]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIbanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal. 2018 Jan 7:39(2):119-177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28886621]

Weil BR, Suzuki G, Young RF, Iyer V, Canty JM Jr. Troponin Release and Reversible Left Ventricular Dysfunction After Transient Pressure Overload. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Jun 26:71(25):2906-2916. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.029. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29929614]

Thygesen K, Mair J, Giannitsis E, Mueller C, Lindahl B, Blankenberg S, Huber K, Plebani M, Biasucci LM, Tubaro M, Collinson P, Venge P, Hasin Y, Galvani M, Koenig W, Hamm C, Alpert JS, Katus H, Jaffe AS, Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. How to use high-sensitivity cardiac troponins in acute cardiac care. European heart journal. 2012 Sep:33(18):2252-7 [PubMed PMID: 22723599]

Meine TJ, Roe MT, Chen AY, Patel MR, Washam JB, Ohman EM, Peacock WF, Pollack CV Jr, Gibler WB, Peterson ED, CRUSADE Investigators. Association of intravenous morphine use and outcomes in acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. American heart journal. 2005 Jun:149(6):1043-9 [PubMed PMID: 15976786]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBonin M, Mewton N, Roubille F, Morel O, Cayla G, Angoulvant D, Elbaz M, Claeys MJ, Garcia-Dorado D, Giraud C, Rioufol G, Jossan C, Ovize M, Guerin P, CIRCUS Study Investigators. Effect and Safety of Morphine Use in Acute Anterior ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018 Feb 10:7(4):. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006833. Epub 2018 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 29440010]

Patrono C, Morais J, Baigent C, Collet JP, Fitzgerald D, Halvorsen S, Rocca B, Siegbahn A, Storey RF, Vilahur G. Antiplatelet Agents for the Treatment and Prevention of Coronary Atherothrombosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Oct 3:70(14):1760-1776. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28958334]

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FDR, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WMM, Binno S, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). European heart journal. 2016 Aug 1:37(29):2315-2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. Epub 2016 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 27222591]