Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is the most common disorder affecting the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of the skeletal muscles. The classic presentation is a fluctuating weakness that is more prominent in the afternoon. It usually involves muscles of the eyes, throat, and extremities. The reduced transmission of electrical impulses across the neuromuscular junction due to the formation of autoantibodies against the specific postsynaptic membrane proteins consequently causes muscle weakness. A wide variety of conditions can precipitate MG, such as infections, immunization, surgeries, and drugs.

Myasthenia gravis causes a significant number of complications. These include myasthenic crisis, an acute respiratory paralysis that requires intensive care, as well as adverse events due to long term medication treatment like opportunistic infections and lymphoproliferative malignancies.

A complete understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, treatment strategies, and complications of myasthenia gravis is necessary for better patient care and outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Myasthenia gravis, similar to other autoimmune disorders, occurs in genetically susceptible individuals. Precipitating factors include conditions like infections, immunization, surgeries, and drugs.

The commonly implicated proteins in the NMJ against which autoantibodies are produced include the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (n-AChR's), muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), and lipoprotein-related protein 4 (LPR4). Agrin–LRP4–MuSK protein complex is essential for the formation and maintenance of NMJ, including the distribution and clustering of the AChR.[1] Approximately 10% of patients with MG have a thymoma, and it is implicated in the production of autoantibodies.[2]

Myasthenia Gravis Classification

Depending on the type of clinical features and the type of antibodies involved, MG can be classified into various subgroups. Each group responds differently to treatment and hence carries a prognostic value:[3]

-

Early-onset MG: Age at onset less than 50 years with thymic hyperplasia

-

Late-onset MG: Age at onset greater than 50 years with thymic atrophy

-

Thymoma-associated MG

-

MG with anti-MuSK antibodies

-

Ocular MG: Symptoms only from periocular muscles

-

MG with no detectable AChR and MuSK antibodies

Epidemiology

Myasthenia gravis has a prevalence of 20 per 100,000 population in the US. It exhibits a female predominance in those less than 40 years of age and a male predominance in those greater than 50 years of age. Childhood MG is quite uncommon in the western populations but is prevalent in Asian countries, with the involvement of around 50% of patients aged less than 15 years. They usually present with symptoms of extraocular muscle weakness.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiologic mechanisms in MG are dependent on the type of antibodies present.

In n-AChR MG, the antibodies are of the IgG1 and IgG3 subtype. They bind to the n-ACh receptor present in the postsynaptic membrane of the skeletal muscles and activate the complement system leading to the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC). MAC brings about the final degradation of the receptors. They may also act by functionally blocking the binding of ACh to its receptor or by enhancing the endocytosis of the antibody-bound n-ACh receptor.

In MusK MG and LPR4 MG, the antibodies are of the IgG4 subtype and do not have the complement activating property. They bind to the Agrin–LRP4–MuSK protein complex in the NMJ, whose primary function is the maintenance of the NMJ, including the n-ACh receptor distribution and clustering. The inhibition of the complex leads to a reduced number of n-ACh receptors.[6][7] The ACh released at the nerve terminal, in turn, is unable to generate the postsynaptic potential required to generate an action potential in muscle due to a reduced number of n-ACh receptors leading to the symptoms of muscle weakness. The weakness is more pronounced with the repeated use of a muscle group since it causes depletion of the ACh store in the NMJ.

Histopathology

The histopathological findings in MG differ by the type of antibodies present.

Muscle: In n-AChR MG, the muscles show significant atrophic changes, whereas, in MuSK MG, there are minimal muscle atrophic changes and significant mitochondrial abnormalities (giant, swollen, and degenerative features). The differences suggest different pathophysiologic mechanisms of the two subtypes of MG. Neurogenic atrophy seems to be prominent in n-AchR MG, whereas mitochondrial abnormalities in MuSK MG.[8]

Thymus: In n-AChR MG, thymus shows epithelial hyperplasia and extra-parenchymal involvement with T-cell areas and germinal centers (GCs).In MuSK MG, the thymus shows age-related changes, and hyperplastic changes are very uncommon. In seronegative MG, infiltrates can be seen in half of the patients.[9] These findings of thymic epithelial hyperplasia and T-cell infiltrate suggest thymus is involved in the production of autoantibodies against the muscle proteins.

History and Physical

The distinguishing clinical feature of MG is the fluctuating muscle weakness that varies in severity, worsens with physical activity, and improves with rest. It can be precipitated by a wide variety of factors like infections, surgery, immunization, heat, emotional stress, pregnancy, drugs (commonly aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, beta-blockers, neuromuscular blocking agents), and worsening of chronic medical illnesses. In history taking, patients should be asked about the timing of the symptoms, at what time of the day do the symptoms usually occurs, as well as improvement with rest. Inquire about subtle signs like coughing after swallowing, increase time to finish eating, hoarseness of the voice, easy fatiguability in the climbing up stairs, and slow and frequent errors in writing or typing; these symptoms are most prominent at the end of the day or work shift.

The most common symptoms include the following:

- Extraocular Muscle Weakness: Around 85% of patients will have this on the initial presentation. Common patient complaints include diplopia, ptosis, or both. These symptoms can progress and cause generalized MG involving the bulbar, axial, and limb muscles in 50% of patients in two years.[10]

- Bulbar Muscle Weakness: This can be the initial presentation in 15% of patients and causes symptoms like difficulty chewing or frequent choking, dysphagia, hoarseness, and dysarthria.[10] The involvement of facial muscles causes an expressionless face, and neck muscle involvement causes a dropped-head syndrome.

- Limb Weakness: This usually involves the proximal muscles more than distal muscles, with the upper limbs more affected than the lower limbs.

- Myasthenic crisis: It is due to the involvement of intercostal muscles and diaphragm and is a medical emergency.

There are no autonomic symptoms like palpitations, bowel, or bladder disturbances that occur in MG as it only involves the nicotinic cholinergic receptors.

The physical examination may reveal normal muscle power because of the fluctuating disease pattern. In such cases, repeated or sustained muscle contractions can demonstrate weakness. Improvement is seen after a period of rest or application of ice (ice-pack test) to the muscle group involved. The pupils, deep tendon reflexes, and sensory examinations are normal.

MuSK MG has clinical features that are quite different from n-AChR MG. It is more common in females, relatively spares extraocular muscles, and commonly involves bulbar, facial, and neck muscles. Myasthenic crisis is also frequent in the MuSK MG.[11]

Clinical Classification: The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) clinical classification divides MG into 5 main classes based on the clinical features and the disease severity. Each class carries different prognoses or responses to therapy.[3]

- Class I: Involves any ocular muscle weakness, including weakness of eye closure. All other muscle groups are normal.

- Class II: Involves mild weakness of muscles other than ocular muscles. Ocular muscle weakness of any severity may be present.

- Class IIa: Involves predominant weakness of the limb, axial muscles, or both. It may also involve the oropharyngeal muscles to a lesser extent.

- Class IIb: Involves mostly oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both. It can have the involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both to a lesser extent.

- Class III: Involves muscles other than ocular muscles moderately. Ocular muscle weakness of any severity can be present.

- Class IIIa: involves the limb, axial muscles, or both predominantly. Oropharyngeal muscles can be involved to a lesser degree.

- Class IIIb: Involves oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both predominantly. The limb, axial muscles, or both can have lesser or equal involvement.

- Class IV: Involves severe weakness of affected muscles. Ocular muscle weakness of any severity can be present.

- Class IVa: Involves limb, axial muscles, or both predominantly. Oropharyngeal muscles can be involved to a lesser degree.

- Class IVb: Involves oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both predominantly. The limb, axial muscles, or both can have lesser or equal involvement. It also includes patients requiring feeding tubes without intubation.

- Class V: Involves intubation with or without mechanical ventilation, except when employed during routine postoperative management.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of MG is mostly clinical. The laboratory investigations and procedures usually aid the clinician in confirming the clinical findings.

Serologic Tests: The anti-AChR Ab test is very specific, and it confirms the diagnosis in patients with classical clinical findings. It is present in four-fifths of patients with generalized MG and only in half of the patients with pure ocular MG. The rest of the patients, about 5% to 10%, will demonstrate anti-MuSK antibodies. Only in a few sporadic cases, both anti-AChR and anti-MuSK antibodies are present in the same patient. The 3% to 50% of the remaining patients who are seronegative to either of these antibodies will demonstrate anti-LRP4 antibodies. Anti-striated muscle antibodies are present in 30% of MG patients. They are more useful as a serologic marker for thymoma, especially in younger patients.[2][9][12]

Electrophysiologic Tests: These are relevant in patients who are seronegative for antibody testing. Commonly employed tests for MG are the repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) test and single-fiber electromyography (SFEMG). Both the tests assess for conduction delays in the NMJ. Routine nerve conduction studies are usually performed to determine the functioning of the nerves and muscles before undertaking these tests.

- RNS Test: This is done by stimulating the nerve at 2-3Hz. Repeated nerve stimulation depletes the ACh in the NMJ, and produces a low excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP). A 10% or more decrease in the EPSP between the first and fifth stimulus is diagnostic of MG.

- SFEMG: This records action potential (AP) from individual muscle fibers, and thus allows to record the AP simultaneously from two muscle fibers innervated by a single motor neuron. The difference between the time of onset of these two action potentials is called the "jitter." In MG, the "jitter" will increase because of the reduced NMJ transmission. This is the most sensitive among the diagnostic tests for MG.

Edrophonium (Tensilon) Test: Edrophonium is a short-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that increases the availability of ACh in the NMJ. This is particularly useful for ocular MG, where electrophysiologic testing cannot be performed. It is administered intravenously, and the patient is observed for improvement in the symptoms of ptosis or diplopia. It has a sensitivity of 71% to 95% for MG diagnosis.[4]

Ice-pack Test: When edrophonium testing is contraindicated, an ice-pack test can be performed. This test requires an ice-pack placed over the eye for 2-5 minutes. Then, an assessment for any improvement in ptosis is done. This test cannot be used for the evaluation of extraocular muscles.

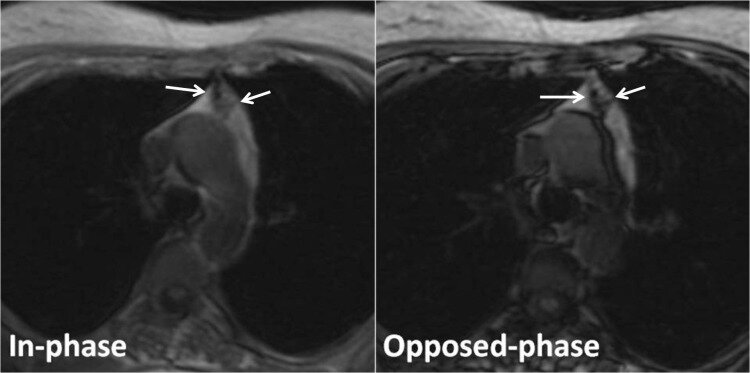

Imaging: Chest computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed in patients diagnosed with MG to assess for thymoma. In cases presenting with pure ocular MG, MRI of orbits and the brain needs to be performed to evaluate for any localized mass lesions.

Other Laboratory Tests: Myasthenia gravis commonly coexists with other autoimmune disorders, and testing for anti-nuclear (ANA) antibodies, rheumatoid factor (RF), and baseline thyroid functions are recommended.

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of treatment in MG involves cholinesterase enzyme inhibitors and immunosuppressive agents. Symptoms that are resistant to primary treatment modalities or those requiring rapid resolution of symptoms (myasthenic crisis), plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulins can be used.

Management strategies in MG are based on the following four principles:

Symptomatic Treatment: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors increases the level of ACh at the NMJ by preventing its enzymatic degradation. Pyridostigmine bromide is preferred over neostigmine because of its longer duration of action. In those with bromide intolerance that leads to gastrointestinal effects, ambenonium chloride can be used. Patients with MuSK MG respond poorly to these drugs and hence may require higher dosages.[13]

Immunosuppressive Treatment: These are indicated in patients who remain symptomatic even after pyridostigmine treatment. Glucocorticoids (prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone) and azathioprine are the first-line immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of MG. Second-line agents include cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, and tacrolimus. These are used when the patient is unresponsive to treatment, has any contraindication to treatment, or intolerability to the use of first-line agents. Recently, various monoclonal antibodies, including rituximab and eculizumab, have been used to treat drug-resistant MG, but data from clinical trials about their efficacy is yet to be documented.[13]

Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) / Plasmapheresis: This is recommended during the perioperative period to stabilize a patient before a procedure. It is also the treatment of choice for the myasthenic crisis due to its rapid onset of action and used in cases that are resistant to immunosuppressive drugs.

Thymectomy: This is indicated for the following:

- Any subtypes of MG with evidence of thymoma.

- Non-thymomatous n-AChR MG, especially in patients aged 15 to 50 years, performed 1-2 years of disease onset.[14]

- Seronegative non-thymomatous MG. (B2)

However, it is not recommended for the non-thymomatous MuSK MG (since thymic pathology is rare) and non-thymomatous ocular MG without secondary generalization.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for myasthenia gravis include the following:

- Lambert-Eaton syndrome is a fluctuating weakness that improves with exercise, differentiating it from MG. This is usually due to underlying malignancy, most commonly small-cell lung cancer. It affects voltage-gated calcium channels in the presynaptic membrane.

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis can present with persistent ocular findings, photophobia, chemosis, and headaches. It is usually abrupt in onset but can be fulminant, and causes can be septic or aseptic.

- Brainstem gliomas are malignant tumors that present with bulbar symptoms, weakness, numbness, balance problems, and seizures depending on its location and structures affected. The symptoms are persistent and usually present with headaches and signs of increased intracranial pressure.

- Multiple sclerosis can present with any neurological sign that may fluctuate or persist over hours to days to weeks secondary to demyelination in the central nervous system. This may present with weakness, sensory deficits, cognitive and behavioral issues. Weakness may be unilateral or bilateral and is usually accompanied by upper motor neuron signs like hyperreflexia, spasticity, and a positive Babinski.

- Botulism presents with ptosis, double vision, progressive weakness, and pupillary abnormalities accompanied by systemic symptoms. Ingestion of honey or contaminated foods may be elicited in the patient's history.

- Tick-borne disease presents with ascending paralysis and respiratory distress and decreased reflexes from a neurotoxin from the saliva of ticks. Minimal constitutional symptoms are seen. It can sometimes present with ophthalmoplegia and bulbar symptoms.

- Polymyositis and dermatomyositis cause proximal muscle weakness and is usually associated with pain. The pathology is the inflammation of the muscle itself.

- Graves ophthalmopathy presents with eyelid retraction and widened palpebral fissure. These are caused by autoantibodies targeted toward the structures of the eye.

Prognosis

Most patients with MG have a near-normal life span with the current treatment modalities. Fifty years ago, the mortality rate was around 50% to 80% in myasthenic crisis, and now it has reduced substantially to 4.47%.[15] Morbidity results from the intermittent muscle weakness leading to aspiration pneumonia and the adverse effects of medications.

Various clinical and laboratory/imaging findings in MG also have a prognostic significance. Studies have shown the following:

- Risk of secondary generalization: This is associated with a late age of onset, high titers of anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibody, and the presence of a thymoma. A recent study predicts this risk by the type of clinical symptoms at the time of presentation. The presence of both ptosis and diplopia at the onset has a higher likelihood of secondary generalization compared to ptosis or diplopia alone.[16] However, early treatment with immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids and azathioprine is associated with reduced risk.

- Risk of MG relapse: Age of onset (<40 years), early thymectomy, and administration of prednisolone are found to be associated with reduced risk of relapse.[17] However, patients with anti-Kv1.4 antibodies and concomitant autoimmune disease showed a high rate of relapse.[16][18]

Complications

The complication of myasthenia gravis includes myasthenic crisis, usually secondary to infections, stress, or acute illnesses.

Treatment complications include long term steroid effects like osteoporosis, hyperglycemia, cataracts, weight gain, hypertension, and avascular necrosis of the hip. There is also the risk of lymphoproliferative malignancies, as well as opportunistic infections such as systemic fungal infections, tuberculosis, and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia with chronic immunosuppressive therapy.

Cholinergic crisis presents due to excessive ACh at nicotinic and muscarinic receptors secondary to the use of cholinesterase inhibitors. Symptoms include cramps, lacrimation, increased salivation, muscular weakness, muscular fasciculation, paralysis, diarrhea, and blurry vision.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is important to stress the value of avoiding precipitants like infections, excessive exertion, emotional stress, worsening of chronic medical illnesses, and drugs (aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, beta-blockers). Patients are advised to take their medications as directed and to avoid taking new medicines without checking with the medical provider. Patients should also be educated about various complications and advised to seek medical care as early as possible. Wearing a medical identification bracelet that shows they have myasthenia gravis is also recommended. Health promotive measures to prevent infections like handwashing and yearly flu vaccine should be emphasized.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Myasthenia gravis, similar to other autoimmune disorders, occurs in genetically susceptible individuals and has no specific cure. Current treatment regimens aim to reduce the level of inflammation and improve the patient's symptoms. It requires sound professional coordination between members of the interprofessional team; this includes the primary care doctor, pharmacist, nurse, physiotherapist, and a neurologist for better patient-centered management and outcome.

The primary care doctor should educate the patient about the precipitating events that could trigger an attack, the treatment modalities available, and the long term complications. The patient should be allowed to choose among the available treatment strategies. The long term treatment of myasthenia gravis requires that the patient be advised about the importance of medication compliance. The family members may be included in the care of the patient once consent is obtained.

The pharmacist educates the patient about drugs that can precipitate an attack, risk of possible drug interactions, and the importance of reaching out to the medical team before taking any newly prescribed medications.

The nurses encourage the patients to follow preventive measures like handwashing, smoking cessation, and age-appropriate vaccinations. These can prevent infections that could trigger a myasthenic attack. In cases where the patient is admitted for a myasthenic crisis, proper coordination between the critical care specialist, nurse practitioner, and the chest physiotherapist ensures a speedy recovery with minimal complications. Awareness about the risk of relapse and the association of myasthenia gravis with other autoimmune disorders reiterates the importance of a regular followup.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Li L, Xiong WC, Mei L. Neuromuscular Junction Formation, Aging, and Disorders. Annual review of physiology. 2018 Feb 10:80():159-188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034255. Epub 2017 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 29195055]

Statland JM, Ciafaloni E. Myasthenia gravis: Five new things. Neurology. Clinical practice. 2013 Apr:3(2):126-133 [PubMed PMID: 23914322]

Gilhus NE, Owe JF, Hoff JM, Romi F, Skeie GO, Aarli JA. Myasthenia gravis: a review of available treatment approaches. Autoimmune diseases. 2011:2011():847393. doi: 10.4061/2011/847393. Epub 2011 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 22007295]

Jayam Trouth A, Dabi A, Solieman N, Kurukumbi M, Kalyanam J. Myasthenia gravis: a review. Autoimmune diseases. 2012:2012():874680. doi: 10.1155/2012/874680. Epub 2012 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 23193443]

Zhang X, Yang M, Xu J, Zhang M, Lang B, Wang W, Vincent A. Clinical and serological study of myasthenia gravis in HuBei Province, China. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2007 Apr:78(4):386-90 [PubMed PMID: 17088330]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVerschuuren JJ, Huijbers MG, Plomp JJ, Niks EH, Molenaar PC, Martinez-Martinez P, Gomez AM, De Baets MH, Losen M. Pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis with antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor, muscle-specific kinase and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4. Autoimmunity reviews. 2013 Jul:12(9):918-23. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.03.001. Epub 2013 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 23535160]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceConti-Fine BM,Milani M,Kaminski HJ, Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006 Nov [PubMed PMID: 17080188]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCenacchi G, Papa V, Fanin M, Pegoraro E, Angelini C. Comparison of muscle ultrastructure in myasthenia gravis with anti-MuSK and anti-AChR antibodies. Journal of neurology. 2011 May:258(5):746-52. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5823-x. Epub 2010 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 21088848]

Leite MI, Jones M, Ströbel P, Marx A, Gold R, Niks E, Verschuuren JJ, Berrih-Aknin S, Scaravilli F, Canelhas A, Morgan BP, Vincent A, Willcox N. Myasthenia gravis thymus: complement vulnerability of epithelial and myoid cells, complement attack on them, and correlations with autoantibody status. The American journal of pathology. 2007 Sep:171(3):893-905 [PubMed PMID: 17675582]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrob D, Arsura EL, Brunner NG, Namba T. The course of myasthenia gravis and therapies affecting outcome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1987:505():472-99 [PubMed PMID: 3318620]

Murthy JMK. Myasthenia Gravis: Do the Subtypes Matter? Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2020 Jan-Feb:23(1):2. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_595_19. Epub 2020 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 32055109]

Juel VC, Massey JM. Myasthenia gravis. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2007 Nov 6:2():44 [PubMed PMID: 17986328]

Melzer N, Ruck T, Fuhr P, Gold R, Hohlfeld R, Marx A, Melms A, Tackenberg B, Schalke B, Schneider-Gold C, Zimprich F, Meuth SG, Wiendl H. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of myasthenia gravis: a supplement to the Guidelines of the German Neurological Society. Journal of neurology. 2016 Aug:263(8):1473-94. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8045-z. Epub 2016 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 26886206]

Gronseth GS, Barohn RJ. Practice parameter: thymectomy for autoimmune myasthenia gravis (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000 Jul 12:55(1):7-15 [PubMed PMID: 10891896]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlshekhlee A, Miles JD, Katirji B, Preston DC, Kaminski HJ. Incidence and mortality rates of myasthenia gravis and myasthenic crisis in US hospitals. Neurology. 2009 May 5:72(18):1548-54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a41211. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19414721]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang L, Zhang Y, He M. Clinical predictors for the prognosis of myasthenia gravis. BMC neurology. 2017 Apr 19:17(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0857-7. Epub 2017 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 28420327]

Wakata N, Iguchi H, Sugimoto H, Nomoto N, Kurihara T. Relapse of ocular symptoms after remission of myasthenia gravis--a comparison of relapsed and complete remission cases. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2003 Apr:105(2):75-7 [PubMed PMID: 12691794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSuzuki S, Nishimoto T, Kohno M, Utsugisawa K, Nagane Y, Kuwana M, Suzuki N. Clinical and immunological predictors of prognosis for Japanese patients with thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2013 May 15:258(1-2):61-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.03.001. Epub 2013 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 23561592]