Introduction

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS), also known as Fong disease or hereditary onycho-osteodysplasia, is a rare multisystemic disease with a classic clinical tetrad of fingernail dysplasia, hypoplasia or absence of the patella, presence of iliac horns, and elbow deformities, although ocular, renal, and neurological involvement exists as well.[1] Dr. E. M. Little first described the phenotype and hereditary nature of what would later become NPS in 1897.[2] However, it was not until the mid 20th century that the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, as well as the condition's genetic penetration, was discovered.[2] NPS can be clinically diagnosed with the characteristic physical exam and radiological imaging findings, although genetic testing and even renal biopsy assist in diagnosis confirmation. Although the prognosis for this condition is good, serious complications exist, and as a result, management recommendations have been proposed.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Nail-patella syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder due to a heterozygous loss of function mutation of the LMXB1 gene on chromosome 9q34.1.[3][4] LMXB1 encodes a transcription factor involved in multiple important embryological developments to include limb dorsal-ventral patterning, differentiation of dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons, skull patterning, periocular mesenchyme development, and renal podocyte development.[3] At least 142 LMXB1 mutations have been identified as well as evidence of somatic mosaicism, which is known to occur in unaffected parents of patients affected by autosomal dominant disorders.[5] NPS is highly penetrant, but there is inter- and intrafamilial variability contributing to the condition’s variable clinical manifestations.[6] Another factor contributing to the condition’s various manifestations may include interactions between the LMXB1 homeodomain with other genes. The PAX2 transcription factor has been studied for its interaction with LMXB1 as both proteins are involved in renal and eye development.[7][8] Mutations of the LMXB1 gene homeodomain have been shown to affect interactions with PAX2 raising the question of the latter’s role in the NPS phenotypic variability, although more research would be needed to test this possibility.[7][8]

Epidemiology

The incidence of nail-patella syndrome has been reported as 1 in 50,000.[1] The genetic basis of this syndrome leads to significant variability in clinical presentation, which may play a role in the skeptical confidence of the reported incidence figure. It is common for families affected by NPS to remain undiagnosed for multiple generations even though the diagnosis can be made at birth, which casts further uncertainty regarding the condition’s true incidence.[1]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of nail-patella syndrome centers around the LMX1B protein role in embryological development. LMX1B is involved in dorsal-ventral limb patterning and has a normal gradient of expression from distal to proximal and from anterior to posterior. This expression pattern likely explains nail and patellar (an epiphyseal equivalent) involvement with decreasing severity of findings going from anterior to posterior as well as going from distal to proximal.[2] It has also been shown that motor axonal migration from the lateral motor columns becomes random with mutations in the LMX1B.[2]

In another example, the anterior structures of the eye to include the cornea, trabecular meshwork, and anterior chamber depth, are each influenced by LMX1B during development. It is an abnormal anterior chamber depth in patients with NPS that is most likely responsible for primary open-angle glaucoma, the most potentially serious and most frequent ocular complication of NPS.[2][1]

LMX1B plays an important role in embryological renal development, particularly with the podocytes and glomeruli. The podocyte foot processes may be effaced and exhibit abnormal slit diaphragms, causing splitting of the glomerular basement membrane as well as decreased endothelial fenestrations.[7][9] These microscopic changes explain why patients with NPS can present with proteinuria with or without hematuria.[7][3]

Histopathology

Electron microscopic and immunohistochemical study of the developing kidney has led to ultrastructural findings related to NPS-related nephropathy. The glomerular basement membrane is seen as irregularly thickened and with a moth-eaten appearance due to the deposition of fibrillar collagen-like material, the latter of which is considered a hallmark of NPS.[9][4] Renal podocytes lack their foot processes, demonstrate slit diaphragms, and demonstrate the abnormal synthesis of proteins that help comprise the glomerular basement membrane and help differentiate glomerular endothelial cells.[9]

History and Physical

Patients with nail-patella syndrome can show decreased upper and lower extremity muscle mass resembling dystrophic muscular disease.[1] Unsurprisingly, nail and patellar changes are characteristic features of this syndrome. Nail changes are present in 98% of patients with NPS and consist of absent, hypoplastic, or dystrophic fingernails and, to a lesser degree, the toenails.[10][11] Each fingernail tends to be more affected along its ulnar aspect, and a pattern of relative hyperextension of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints along with flexion of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints known as a swan-neck deformity may be seen.[1][10] Loss of the normal skin creases over the DIP joints can be seen and has been reported as a sensitive finding for NPS.[1][10]

Similar to the nails, patients with NPS have absent, hypoplastic, or irregular patellae, which frequently sublux superolaterally, although the non-displaced position of the patella may be naturally lateral and superior.[1] Abnormalities of the distal femur, as well as the primary muscles responsible for knee flexion and extension, may also be seen.

Limited elbow joint range of motion in extension, pronation, and supination may be elicited. Skin contractures and superficial web-like membranes called pterygia at the elbow joint can be seen.[1] Bilateral, symmetric bony processes of the iliac bones called iliac horns are present in roughly 70% of cases and are pathognomic for NPS.[10] These processes represent corticomedullary tissue continuous with the iliac bones at the level of the gluteus medius muscle origin.[11] Interestingly, even though the bone mineral density of the hip and spine has been shown to be slightly decreased in patients with NPS, patients are at elevated risk for long bone fractures for reasons that are not fully understood.[12]

Extraskeletal systemic manifestations of NPS are notable for renal, ophthalmic, and neurological involvement. Renal involvement has been reported in 30-60% of patients with NPS, and the degree of severity is the dominant factor that influences mortality, as progression to renal failure can occur rapidly and in as much as 10% of patients.[1][4]

The most common ophthalmic findings are open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension, which present earlier in patients with NPS compared to the unaffected population but are treatable and preventable with screening measures.[1] A zone of darkened pigmentation about the iris called Lester’s sign has been described in patients with NPS, although the finding is non-specific.[1]

Common neurological symptoms can include numbness, tingling, and neuropathic pain in a non-peripheral nerve or dermatomal pattern, which affect the distal more so than the proximal limb.[1][13]

Evaluation

Laboratory Evaluation

Nail-patella syndrome with renal involvement can be suspected on routine urinalysis, as evidenced by proteinuria with or without hematuria, which is usually the initial manifestations.[1] Renal biopsy is confirmatory.

Imaging Evaluation

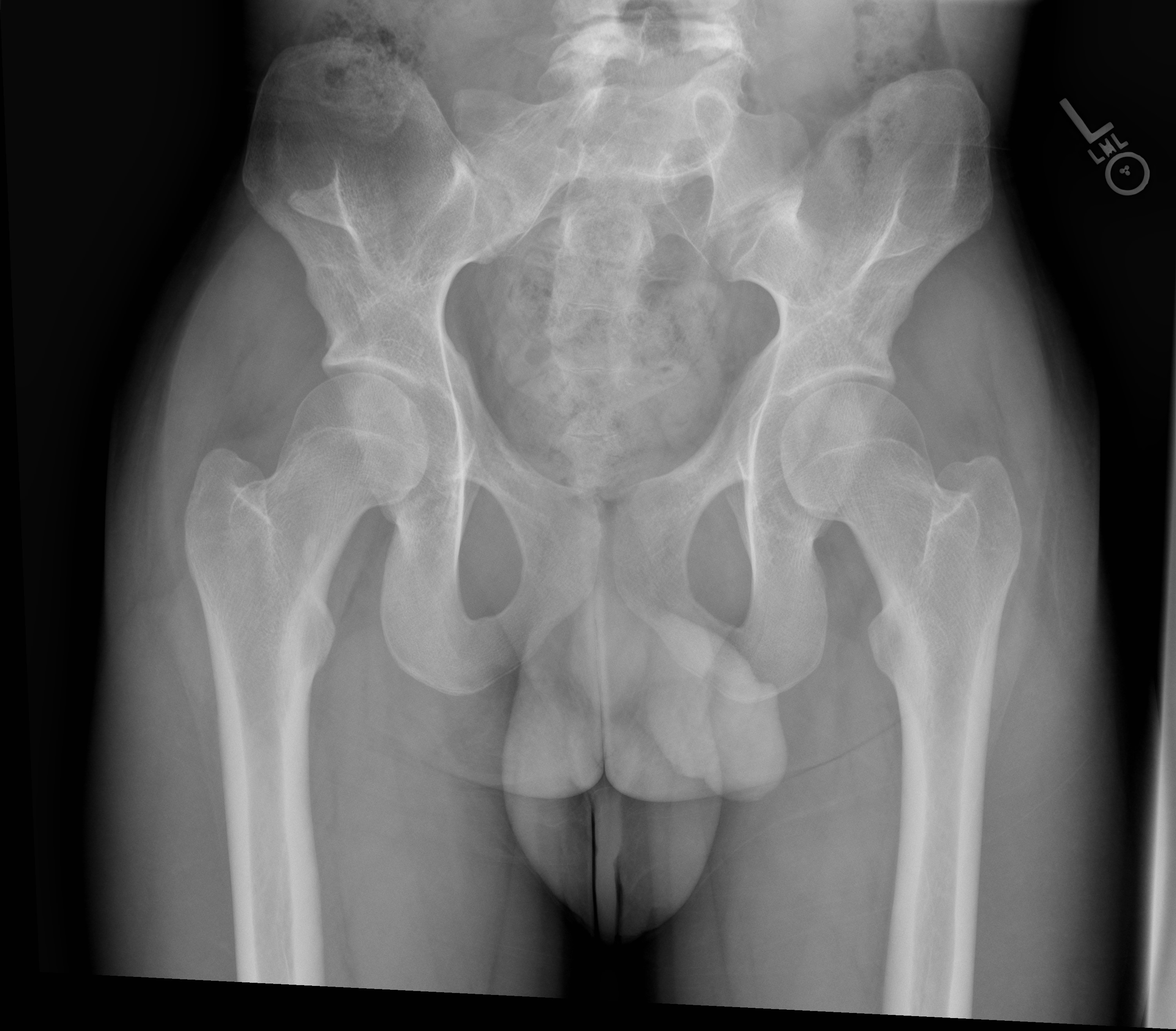

Radiography plays an important role in diagnosing NPS with most of the condition’s musculoskeletal characteristics evident on radiographs. The knee will demonstrate a small or absent patella in addition to various morphological abnormalities of the femoral condyles and trochlea.[14] One case report described the presence of a midline band of synovial tissue or plicae located within the intercondylar notch clearly seen on MRI but not on plain films.[15] Bilateral iliac horns can be seen on radiographs of the pelvis and, when present, are considered pathognomonic. Radial head dysplasia and its complications to include subluxation are also readily apparent on radiographs.

Treatment / Management

Medical Treatment

Treatment of renal involvement is focused on slowing the progression of proteinuria by achieving blockage of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Two classes of drugs that target the RAAS and are well studied in patients with genetic or acquired proteinuria are angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). The literature is lacking robust evidence to support any particular medical treatment, although the authors of a case report involving an infant girl with NPS and proteinuria described complete remission of the patient's proteinuria using a combination therapy of an ACEi and ARB.[16] Progression to end-stage renal disease is possible, for which the only treatment is renal transplantation.[16][4] Some authors have suggested a trial of cyclosporin in patients who fail ACEi therapy due to cyclosporin's ability to reduce proteinuria in patients with Alport syndrome, a genetic disease that also affects the glomerular basement membrane.[7](B3)

Surgical Treatment

Patellofemoral pain and patellar dislocation are common symptoms of NPS, which may be initially treated with conservative measures. Multiple surgical techniques and approaches have been described for the correction of patellar instability.[15][17] Interestingly, one such surgical approach aims to resect a synovial band or plicae, which can contribute to patellar dislocation.[15] Surgical removal of this synovial band has been reported to improve symptoms, but long-term outcomes of the procedure require further investigation.[15][17] One survey in the Netherlands showed the majority of patients with NPS with knee symptoms were at least satisfied with their surgery, but the reported rate of patellar instability was the same between patients who underwent surgery and those who did not.[17](B3)

Patient Management

No specific management guidelines have been proposed by any large medical organization. Sweeney et al. put forth recommendations that aim to maintain quality of life, provide genetic counseling for patients and their families, and provide screening measures to prevent NPS complications associated with elevated morbidity and mortality such as glaucoma and renal failure.[1] [Level 5]

Differential Diagnosis

The combination of musculoskeletal and systemic findings in nail-patella syndrome is characteristic, but because the clinical manifestations are varied and nonspecific, there is overlap with other genetic conditions. In their review article, Sweeney et al. offered a broad differential and listed the similarities and differences in each differential diagnosis with regards to NPS.[1]

Prognosis

Patients with NPS live a normal lifespan, and the reported association with malignancy is favored to be coincidental.[1] Conservative and operative treatment strategies exist for patients with patellofemoral symptoms. Glaucoma and nephropathy are two potentially serious manifestations that are treatable and preventable with screening. In the case of nephropathy, patients with proteinuria or hypertension can be treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and, ultimately, with renal transplantation.[4]

Complications

The most potentially serious complications of NPS are acute open-angle glaucoma and renal failure. The prevalence of glaucoma has been reported at nearly 17% in patients over the age of 40 and is treatable and preventable with screening.[1] Renal failure is the most feared complication of NPS and is the primary complication affecting mortality.[1] The progression to renal failure in patients with NPS nephropathy can occur rapidly or after many years for reasons that are not fully understood.[1] Like glaucoma, nephropathy is treatable and more importantly preventable with screening.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with NPS have multiple abnormalities, which can make understanding the various clinical manifestations of their condition challenging. A multidisciplinary approach is likely best, with most patients treated conservatively. Genetic counseling should be offered to all patients with nail-patella syndrome and their families. Emphasis should be placed on screening for serious complications, particularly nephropathy and glaucoma.

Pearls and Other Issues

- NPS is a rare multisystemic genetic condition with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern involving mutations of the LMX1B protein leading to various yet characteristic clinical manifestations.

- The classic clinical tetrad of NPS consists of the involvement of the nails, knees, elbows, and the presence of iliac horns, each of which is readily apparent on physical exam and/or imaging. Iliac horns are pathognomonic for the condition.

- Renal failure is an uncommon but serious complication and the primary influencer of patient mortality.

- Prognosis is good with screening precautions and early intervention of symptoms under the care of an interprofessional healthcare team.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Despite the well-documented phenotype of patients with nail-patella syndrome, this rare genetic condition can make for a challenging diagnosis as there are potentially multiple clinical manifestations, and diagnosis can be delayed into adulthood. Additionally, there are potentially serious complications of NPS if patient symptoms are not addressed. Due to these challenges, patients would likely benefit from an interprofessional healthcare team of pediatricians, primary care physicians, medical geneticists, nephrologists, radiologists, and orthopedic surgeons who collaborate to perform screening for complications, treat symptomatic complaints as they arrive, and ensure appropriate referral to subspecialist providers when medically warranted.[1][10] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sweeney E, Fryer A, Mountford R, Green A, McIntosh I. Nail patella syndrome: a review of the phenotype aided by developmental biology. Journal of medical genetics. 2003 Mar:40(3):153-62 [PubMed PMID: 12624132]

McIntosh I, Dunston JA, Liu L, Hoover-Fong JE, Sweeney E. Nail patella syndrome revisited: 50 years after linkage. Annals of human genetics. 2005 Jul:69(Pt 4):349-63 [PubMed PMID: 15996164]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee BH, Cho TJ, Choi HJ, Kang HK, Lim IS, Park YH, Ha IS, Choi Y, Cheong HI. Clinico-genetic study of nail-patella syndrome. Journal of Korean medical science. 2009 Jan:24 Suppl(Suppl 1):S82-6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S82. Epub 2009 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 19194568]

Chaturvedi S, Pulimodd A, Agarwal I. Quiz page December 2013: Hypoplastic nails, bowed elbows, and nephrotic syndrome. Nail-patella syndrome (hereditary osteo-onychodysplasia, Turner-Keiser syndrome, Fong disease). American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013 Dec:62(6):A25-7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.05.027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24267390]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarini M, Bocciardi R, Gimelli S, Di Duca M, Divizia MT, Baban A, Gaspar H, Mammi I, Garavelli L, Cerone R, Emma F, Bedeschi MF, Tenconi R, Sensi A, Salmaggi A, Bengala M, Mari F, Colussi G, Szczaluba K, Antonarakis SE, Seri M, Lerone M, Ravazzolo R. A spectrum of LMX1B mutations in Nail-Patella syndrome: new point mutations, deletion, and evidence of mosaicism in unaffected parents. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010 Jul:12(7):431-9. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e21afa. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20531206]

Sato U, Kitanaka S, Sekine T, Takahashi S, Ashida A, Igarashi T. Functional characterization of LMX1B mutations associated with nail-patella syndrome. Pediatric research. 2005 Jun:57(6):783-8 [PubMed PMID: 15774843]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLemley KV. Kidney disease in nail-patella syndrome. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2009 Dec:24(12):2345-54. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0836-8. Epub 2008 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 18535845]

Marini M, Giacopelli F, Seri M, Ravazzolo R. Interaction of the LMX1B and PAX2 gene products suggests possible molecular basis of differential phenotypes in Nail-Patella syndrome. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2005 Jun:13(6):789-92 [PubMed PMID: 15785774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWitzgall R. How are podocytes affected in nail-patella syndrome? Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2008 Jul:23(7):1017-20. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0714-9. Epub 2008 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 18253764]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrice A, Cervantes J, Lindsey S, Aickara D, Hu S. Nail-patella syndrome: clinical clues for making the diagnosis. Cutis. 2018 Feb:101(2):126-129 [PubMed PMID: 29554154]

Lo Sicco K, Sadeghpour M, Ferris L. Nail-patella syndrome. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2015 Jan:14(1):85-6 [PubMed PMID: 25763426]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTowers AL, Clay CA, Sereika SM, McIntosh I, Greenspan SL. Skeletal integrity in patients with nail patella syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2005 Apr:90(4):1961-5 [PubMed PMID: 15623820]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDunston JA, Reimschisel T, Ding YQ, Sweeney E, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, McIntosh I. A neurological phenotype in nail patella syndrome (NPS) patients illuminated by studies of murine Lmx1b expression. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2005 Mar:13(3):330-5 [PubMed PMID: 15562281]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTigchelaar S, Rooy Jd, Hannink G, Koëter S, van Kampen A, Bongers E. Radiological characteristics of the knee joint in nail patella syndrome. The bone & joint journal. 2016 Apr:98-B(4):483-9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B4.37025. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27037430]

Lippacher S, Mueller-Rossberg E, Reichel H, Nelitz M. Correction of malformative patellar instability in patients with nail-patella syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2013 Oct:99(6):749-54. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.03.031. Epub 2013 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 24029584]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceProesmans W, Van Dyck M, Devriendt K. Nail-patella syndrome, infantile nephrotic syndrome: complete remission with antiproteinuric treatment. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2009 Apr:24(4):1335-8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn725. Epub 2009 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 19147669]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTigchelaar S, Lenting A, Bongers EM, van Kampen A. Nail patella syndrome: Knee symptoms and surgical outcomes. A questionnaire-based survey. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2015 Dec:101(8):959-62. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.09.033. Epub 2015 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 26596417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence