Introduction

Hysterosalpingogram (HSG) is an imaging procedure in which contrast dye is injected into the uterine cavity, progresses into the fallopian tubes, and ultimately reaches the fimbriated ends adjacent to the ovaries. Fluoroscopy and x-ray images are taken at various stages of the procedure to assess filling, uterine shape, tubal patency, and peritoneal spillage to evaluate the structure of the endometrial cavity and patency of the fallopian tubes. This diagnostic modality is primarily utilized in assessing female infertility. Structural endometrial cavity and fallopian tube abnormalities contribute significantly to infertility, with up to 60% of cases attributed to such issues.[1]

The ability to specifically evaluate fallopian tube patency and endometrial cavity structure is unique to HSG, which is often utilized as a complementary procedure with other imaging modalities (eg, pelvic ultrasonography, hysteroscopy, or magnetic resonance imaging) to assess anatomic infertility etiologies.[2][3] Advancements in contrast agents have improved the safety and tolerance of HSG, with modern nonionic, iso-osmolar agents offering enhanced patient comfort. HSG has some contraindications and associated complications; however, the procedure remains a cornerstone in the diagnostic evaluation of female infertility. Therefore, clinicians should understand how to integrate the HSG procedure into an infertility evaluation, ensuring optimal patient care and accurate interpretation of results.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The anatomical structures primarily assessed during an HSG are the fallopian tubes and the endometrial cavity. In patients with normal anatomic reproductive structures, the fallopian tubes are patent and attach to the uterus at the interstitial space. During ovulation, the oocytes released from the ovaries pass through the patent fallopian tube lumens into the endometrial cavity. Each fallopian tube is on either side of the uterus, with the fimbriated end located near the ovary distally and the proximal end attached to the uterine cornua. The fallopian tubes are usually divided into 3 main segments: the infundibulum, ampulla, and isthmus.

An HSG assists clinicians in identifying the patency and contour of the endometrial cavity and fallopian tubes and excludes tubal obstruction or endometrial structural abnormalities as the etiology of female infertility. "Tubal infertility" or "tubal factors" refers to congenital conditions or conditions that cause tubal damage, resulting in female infertility. The most common cause of tubal occlusions is sexually transmitted infections. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is associated with approximately 90% of infertility cases.[4] A recent systematic review demonstrated a positive correlation between >75% of patients with Chlamydia trachomatis infection and female infertility. However, tubal occlusion can also be seen in other conditions, including endometriosis, pelvic adhesions secondary to surgical procedures, or medically managed ectopic pregnancies. False-positive findings for tubal occlusion can result due to tubal spams, which may occur during an HSG procedure in patients with normal anatomic structures.[5]

Uterine abnormalities may also lead to fertility issues. Damage to the endometrial cavity, which results in intrauterine synechiae, can obliterate the endometrial cavity and result in an inability to visualize patent fallopian tubes during an HSG.[6] Congenital conditions are classified based on Mullerian abnormalities, primarily agenesis, unicornuate, didelphys, bicornuate, septate, arcuate, and diethylstilbestrol-related uterine anomalies. These structural abnormalities distort the endometrial cavity and may obstruct the fallopian tubes, all of which are readily detected when performing an HSG.[7] Mullerian abnormalities are diagnosed in approximately 5% of all hysterosalpingograms.[8]

Additional pathologies found on HSG include other obstructive etiologies, including uterine cancer, polyps, fibroids, and adhesions. Although other imaging modalities are superior in visualizing these pathologies, HSG may have limited benefits. Therefore, performing pelvic ultrasonography concurrently with HSG during the diagnostic evaluation of female infertility is essential as a complimentary diagnostic evaluation.[9]

Indications

An HSG is primarily indicated in patients with infertility to assess the patency and contour of the endometrial cavity and fallopian tubes and excludes tubal obstruction or endometrial structural abnormalities as the underlying etiology. Other imaging modalities (eg, pelvic ultrasonography) may be used to detect other pathologies.[10]

Contraindications

Contraindications for HSG include an ongoing pregnancy, pelvic infection, or current heavy uterine bleeding. Performing an HSG during the early follicular phase may help to avoid potential overlap with an otherwise viable gestation; however, given that infertility is usually the indication for the HSG in the first place, this concern is less common. An additional benefit is a thin endometrial lining, which aids image interpretation. Nonetheless, a urine pregnancy test should be performed to ensure no concurrent pregnancy. A history of pelvic inflammatory disease is not a direct contraindication for a hysterosalpingogram, though postprocedure infection may occur in 1.4% to 3.4% of cases. Antibiotics may reduce this risk but are not recommended for routine administration.[11]

A media contrast allergy is also a contraindication. Therefore, allergies to iodine must be addressed with the patient. Furthermore, if the patient has a history of thyroid disease, the procedure should be discussed with her endocrinologist, as using iodine can lead to a Wolff-Chaikoff effect, a presumed reduction in thyroid hormone levels, or exacerbate thyrotoxicosis in patients with a history of Grave disease.[12] Premedicating select patients before an HSG with glucocorticoids has been suggested; however, radiologists have found insufficient evidence to support this approach. Noniodine contrast should be used in patients with iodine allergies.

Equipment

Equipment typically required during an HSG procedure includes a speculum, fluoroscopic table, betadine vaginal and cervical solution, a long tenaculum to hold the uterine cervix, and a cannula for dye administration. A metal cannula with a rubber acorn tip, a plastic catheter with an inflatable balloon, or a thin catheter and shallow acorn may be used.[13]

Personnel

HSG is most commonly performed in a radiology suite by a radiology technician. However, an OB/GYN clinician can also perform the procedure in the office or clinic setting. In most cases, only a single operator is required to perform this procedure.

Preparation

HSG should be ideally scheduled during the first half of the menstrual cycle, days 1 to 14, to reduce the chance of concurrent pregnancy. Pain mitigation strategies include prophylactic oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and endocervical local anesthesia. Often, clinicians administer an over-the-counter pain reliever in the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug class (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, or indomethacin) an hour before the procedure. However, studies have not demonstrated significant pain reduction using prophylaxis.[14][15]

Prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely administered but may be prescribed for patients with a history of pelvic inflammatory disease or prior infection at the clinician's discretion.[16] Premedication with the antispasmodic, anticholinergic drug hyoscine-N-butyl bromide may reduce pain during and after an HSG as well as decrease proximal tubal spasms. However, studies have limited evidence of this benefit; therefore, routine use is not recommended.[17] Most patients can transport themselves home after having HSG. However, based on the patient's preference and postprocedural recovery, they should be advised to make arrangements for assistance.

Technique or Treatment

Hysterosalpingogram Technique

An HSG procedure comprises the following steps:

- Place the patient on the examination table in the dorsal lithotomy position.

- Insert a speculum into the vaginal vault and visualize the cervix. Clease the cervix and vaginal vault in the usual manner with betadine or equivalent surgical site preparation solution.

- Inject the cervical stroma with local anesthesia.

- Stabilize the cervix with a tenaculum and introduce the metal cannula with a rubber acorn tip through the cervical os; ensure an adequate seal. Alternative catheters may also be used, including plastic catheters with inflatable balloons or thin catheters with shallow acorn tips. Before catheter placement, contrast should be injected through the device to avoid air in the endometrial cavity, which can interfere with images.

- Use the tenaculum to manipulate the uterus as needed to ensure complete visualization with the radiographs.[18]

- Obtain a scout radiograph of the pelvis before the contrast medium is instilled. Inject the contrast slowly to decrease patient discomfort.

- Fill the uterine cavity with radioopaque media, typically 1 to 3 mL initially, and perform multiple pelvic x-rays to visualize the spread of the media from the uterine cavity into the fallopian tubes, eventually reaching fimbriated ends next to the ovaries.

Hysterosalpingogram Imaging

During the HSG procedure, the following images are obtained at a minimum:

- Early filling of the uterus with contrast to detect defects

- After complete filling of the uterus to detect uterine shape

- Flow of contrast through the fallopian tubes

- Spill of contrast into the free peritoneal space

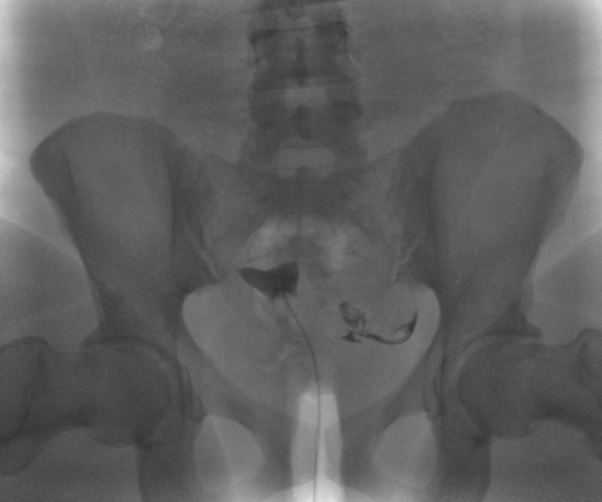

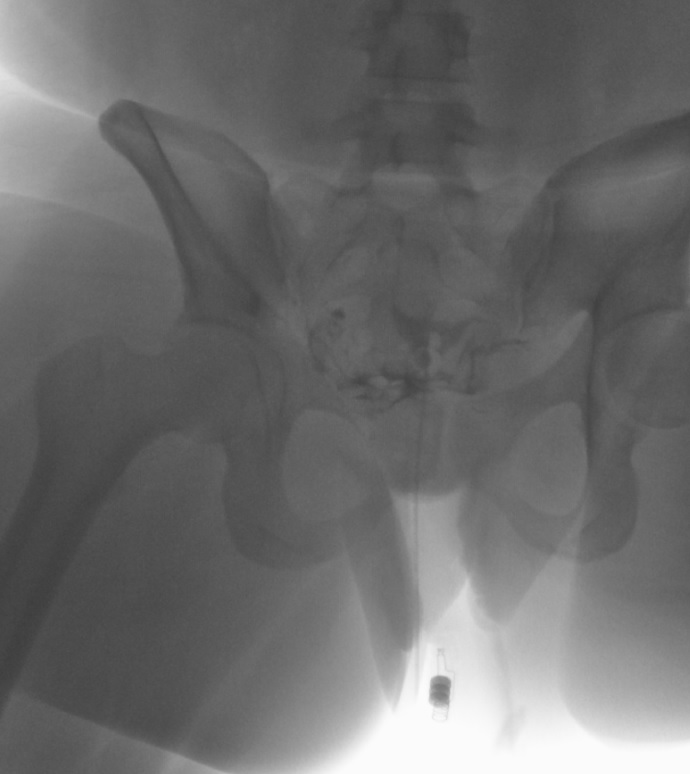

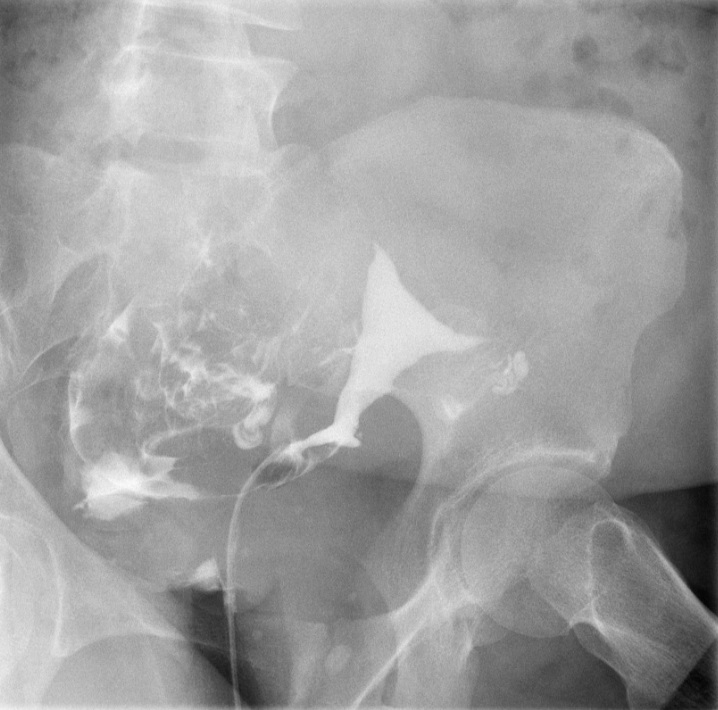

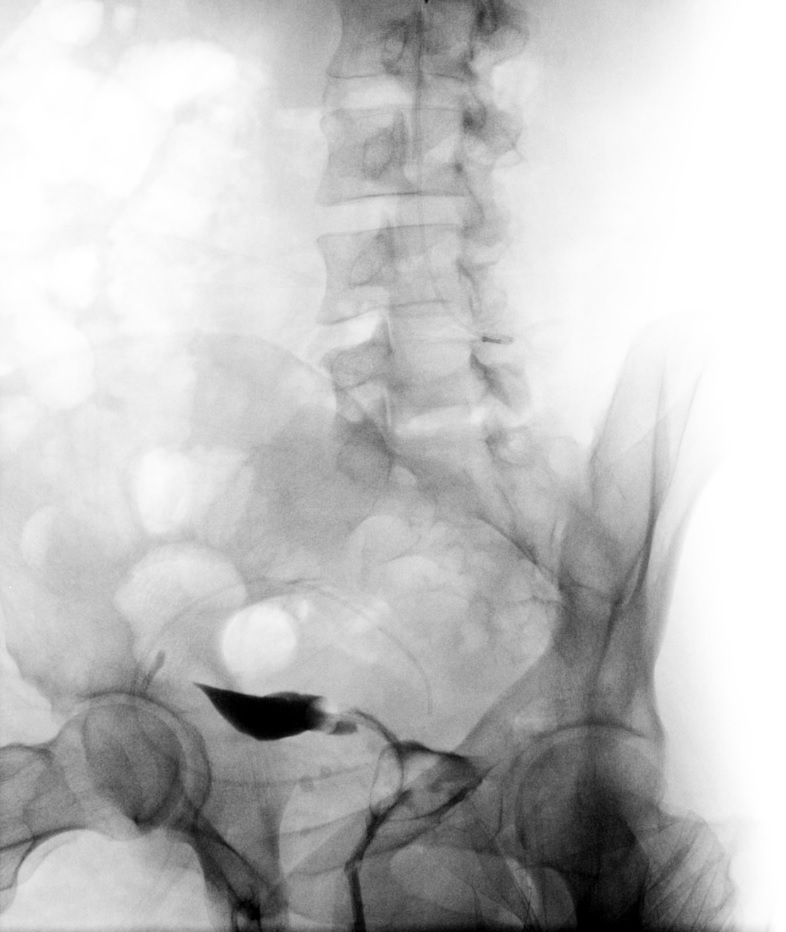

The exact number of the images obtained is institution-dependent. Filling of the endometrial cavity is continued until the media is observed to flow from each fallopian tube (see Images. Patent Fallopian Tubes and Bilateral Patent Fallopian Tubes). The hysterosalpingogram mainly visualizes the areas with continued patency to the uterine cavity where the contrast is deposited (see Image. Hysterosalpingogram Image Following Contrast Media Installation). In cases where at least 1 fallopian tube does not demonstrate contrast flow, intravenous anticholinergic medication can be given to rule out the possibility of fallopian tube smooth muscle spasms. The contrast media appears hyperdense in imaging, thus allowing for the visualization of the media’s pathway. Failure to see the expected flow of contrast media into the peritoneal cavity from either fallopian tube is evidence of an occlusion. See Images. Right Fallopian Tube Occlusion, Left Fallopian Tube Occlusion, Bilateral Fallopian Tube Occlusion, Endometrial Cavity Image on Hysterosalpingogram, and Peritoneal Dye Spillage on Hysterosalpingogram for examples of contrast flow imaging and interpretation.

The media used is a radio-opaque dye that has varied over the years. By reducing osmolality, water-soluble contrast agents have improved safety and patient tolerance for HSG. Initially, contrast media agents were hyperosmolar (> 1000 mOsmol/kg) and ionic. Plasma typically has an osmolarity of between 275 to 290 mOsm/kg. Subsequently, nonionic agents with 2 to 3 times the osmolality of plasma were developed. Nonionic iso-osmolar contrast agents (eg, iodixanol and iotrolan) are now available.[19] While there is a wide variety of available agents, there is no consensus on which is preferable for HSG procedures.[20]

Complications

Overall, severe complications following HSG are rare, with the most common complications being abdominal cramping and vaginal bleeding, which may persist for a few days following the procedure.[21] Other complications include allergic reactions to the dye, pelvic infection, and injury to the uterus or cervix.

Rarely, patients may experience a vasovagal reaction due to the manipulation of the cervix. Patients should be advised to contact their OB/GYN clinician if they develop foul-smelling discharge, severe abdominal pain, heavy vaginal bleeding, fever or chills, or syncope. A case report of retained products of conception found during an HSG with associated intravasation of contrast media was published, which resulted in later volume overload during subsequent hysteroscopic procedures.[22]

Clinical Significance

Hysterosalpingogram remains a crucial component in the diagnostic evaluation of female infertility and serves as a complementary imaging modality to other studies, including pelvic ultrasonography, hysteroscopy, magnetic resonance, and laparoscopy with chromotubation. Laparoscopy with chromotubation often helps identify and simultaneously treat tubal and nontubal factors, including intraabdominal and pelvic adhesions and endometriosis. HSG helps evaluate tubal and intrauterine abnormalities (eg, synechiae and polyps).[23] Each modality can provide helpful information for assessing female infertility, but no single study provides a comprehensive assessment. Thus, a combination of transvaginal ultrasonography, HSG, and hysteroscopy is frequently recommended to evaluate patients with infertility.[24]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional healthcare teams, including gynecologists, anesthesiologists, radiology technicians, nurses, and additional healthcare professionals, are crucial in ensuring optimal patient care during HSG procedures. Effective communication and collaboration among team members are essential to prevent medical errors and optimize patient outcomes. Meticulous documentation and interprofessional communication enable prompt reactions to patient status changes, including diagnostic test results. This collaborative approach drives improved diagnosis and targeted treatment strategies, enhancing patient-centered care, safety, and team performance. HSG, typically performed by a radiology technician or OB/GYN clinician, requires coordinated efforts among team members to achieve procedural success and patient well-being.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Peritoneal Dye Spillage on Hysterosalpingogram. Following the infilling of the endometrial cavity with dye, this hysterosalpingogram image reveals bilateral dye spillage into the peritoneal cavity, which is evidence of bilateral tubal patency.

Contributed by DJ Martingano, DO, MBA, PhD, FACOG, FACPM, FMIGS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Endometrial Cavity Image on Hysterosalpingogram. Following the infilling of the endometrial cavity with dye, this hysterosalpingogram image reveals a normal endometrial cavity but an absence of flow through the fallopian tubes bilaterally and no dye spillage into the peritoneal cavity, which is evidence of bilateral tubal occlusion.

Contributed by DJ Martingano, DO, MBA, PhD, FACOG, FACPM, FMIGS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Hysterosalpingogram Image Following Contrast Media Installation. Following the infilling of the endometrial cavity with dye, this hysterosalpingogram image reveals a normal endometrial cavity but an absence of flow through the fallopian tubes bilaterally and no dye spillage into the peritoneal cavity, which is evidence of bilateral tubal occlusion.

Contributed by DJ Martingano, DO, MBA, PhD, FACOG, FACPM, FMIGS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Left Fallopian Tube Occlusion. Following infilling the endometrial cavity with dye, this hysterosalpingogram image reveals dye within the right fallopian tube with dye spillage into the peritoneal cavity but no dye within the left fallopian tube. These findings are evidence of right fallopian tube patency and left tubal occlusion.

Contributed by DJ Martingano, DO, MBA, PhD, FACOG, FACPM, FMIGS

References

Dolinko AV, Danilack VA, Alvero RJ, Snegovskikh VV. Utility of Repeat Uterine Cavity Evaluation in the Infertility Workup. Journal of women's health (2002). 2024 Feb:33(2):171-177. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2023.0302. Epub 2023 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 38117546]

Hou JH, Lu BJ, Huang YL, Chen CH, Chen CH. Outpatient hysteroscopy impact on subsequent assisted reproductive technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis in patients with normal transvaginal sonography or hysterosalpingography images. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E. 2024 Feb 1:22(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12958-024-01191-0. Epub 2024 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 38302947]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMakwe CC, Ugwu AO, Sunmonu OH, Yusuf-Awesu SA, Ani-Ugwu NK, Olumakinwa OE. Hysterosalpingography findings of female partners of infertile couple attending fertility clinic at Lagos University Teaching Hospital. The Pan African medical journal. 2021:40():223. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.223.29890. Epub 2021 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 35145585]

Tsevat DG, Wiesenfeld HC, Parks C, Peipert JF. Sexually transmitted diseases and infertility. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Jan:216(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28007229]

Ng KYB, Cheong Y. Hydrosalpinx - Salpingostomy, salpingectomy or tubal occlusion. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2019 Aug:59():41-47. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30824209]

Ahmadi F, Siahbazi S, Akhbari F, Eslami B, Vosough A. Hysterosalpingography finding in intra uterine adhesion (asherman' s syndrome): a pictorial essay. International journal of fertility & sterility. 2013 Oct:7(3):155-60 [PubMed PMID: 24520480]

Ledbetter KA, Shetty M, Myers DT. Hysterosalpingography: an imaging Atlas with cross-sectional correlation. Abdominal imaging. 2015 Aug:40(6):1721-32. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0284-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25389063]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReyes-Muñoz E, Vitale SG, Alvarado-Rosales D, Iyune-Cojab E, Vitagliano A, Lohmeyer FM, Guevara-Gómez YP, Villarreal-Barranca A, Romo-Yañez J, Montoya-Estrada A, Morales-Hernández FV, Aguayo-González P. Müllerian Anomalies Prevalence Diagnosed by Hysteroscopy and Laparoscopy in Mexican Infertile Women: Results from a Cohort Study. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2019 Oct 17:9(4):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9040149. Epub 2019 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 31627332]

Passos LG, Terraciano P, Wolf N, Oliveira FDS, Almeida I, Passos EP. The Correlation between Chlamydia Trachomatis and Female Infertility: A Systematic Review. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2022 Jun:44(6):614-620. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1748023. Epub 2022 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 35576969]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMaheux-Lacroix S, Bergeron C, Moore L, Bergeron MÈ, Lefebvre J, Grenier-Ouellette I, Dodin S. Hysterosalpingosonography Is Not as Effective as Hysterosalpingography to Increase Chances of Pregnancy. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2019 May:41(5):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 30595514]

. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 195: Prevention of Infection After Gynecologic Procedures. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:131(6):e172-e189. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002670. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29794678]

Ma G, Mao R, Zhai H. Hyperthyroidism secondary to hysterosalpingography: an extremely rare complication: A case report. Medicine. 2016 Dec:95(49):e5588. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005588. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27930576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChahine R, Zadeh C, Zeid FA, Al-Kutoubi A. Hysterosalpingography: a step up for dose reduction. Clinical radiology. 2024 Jan:79(1):e89-e93. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2023.10.001. Epub 2023 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 37923624]

Canday M, Yurtkal A, Kirat S. Evaluation and perspectives on hysterosalpingography (HSG) procedure in infertility: a comprehensive study. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2023 Aug:27(15):7107-7117. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202308_33284. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37606121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHindocha A, Beere L, O'Flynn H, Watson A, Ahmad G. Pain relief in hysterosalpingography. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015 Sep 20:2015(9):CD006106. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006106.pub3. Epub 2015 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 26387564]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrun JL, Castan B, de Barbeyrac B, Cazanave C, Charvériat A, Faure K, Mignot S, Verdon R, Fritel X, Graesslin O, CNGOF, SPILF. Pelvic inflammatory diseases: Updated French guidelines. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction. 2020 May:49(5):101714. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101714. Epub 2020 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 32087306]

Aboshama RA, Shareef MA, AlAmodi AA, Kurdi W, Al-Tuhaifi MM, Bintalib MG, Sileem SA, Abdelazem O, Abdelhakim AM, Sobh AMA, Elbaradie SMY. The effect of hyoscine-N-butylbromide on pain perception during and after hysterosalpingography in infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Human fertility (Cambridge, England). 2022 Jul:25(3):422-429. doi: 10.1080/14647273.2020.1842915. Epub 2020 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 33140669]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMansour R, Nada A, El-Khayat W, Abdel-Hak A, Inany H. A simple and relatively painless technique for hysterosalpingography, using a thin catheter and closing the cervix with the vaginal speculum: a pilot study. Postgraduate medical journal. 2011 Jul:87(1029):468-71. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2010.106658. Epub 2011 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 21586792]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohd Nor H, Jayapragasam K, Abdullah B. Diagnostic image quality of hysterosalpingography: ionic versus non ionic water soluble iodinated contrast media. Biomedical imaging and intervention journal. 2009 Jul:5(3):e29. doi: 10.2349/biij.5.3.e29. Epub 2009 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 21611058]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePeart JM, Sim RG, Hofman PL. Therapeutic effects of hysterosalpingography contrast media in infertile women: what do we know about the H2O in the H2Oil trial and why does it matter? Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2021 Feb 18:36(3):529-535. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa325. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33326555]

Kılıç KK, Gürses C, Karadağ C, Sözel YK, Özdemir Ö. When a balloon catheter or tenaculum is required for cervical traction during hysterosalpingography. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2023 Dec:43(1):2171777. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2023.2171777. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36708520]

Tobler KJ, Oman S, Kolp LA. Retained Products of Conception Associated with Intravasation of Hysterosalpingogram Contrast and Hysteroscopic Distention Media: A Case Report. The Journal of reproductive medicine. 2016 Jan-Feb:61(1-2):69-72 [PubMed PMID: 26995892]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePanda SR, Kalpana B. The Diagnostic Value of Hysterosalpingography and Hysterolaparoscopy for Evaluating Uterine Cavity and Tubal Patency in Infertile Patients. Cureus. 2021 Jan 6:13(1):e12526. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12526. Epub 2021 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 33569257]

Wadhwa L, Rani P, Bhatia P. Comparative Prospective Study of Hysterosalpingography and Hysteroscopy in Infertile Women. Journal of human reproductive sciences. 2017 Apr-Jun:10(2):73-78. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_123_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28904493]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence