Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Osborne Band

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Osborne Band

Introduction

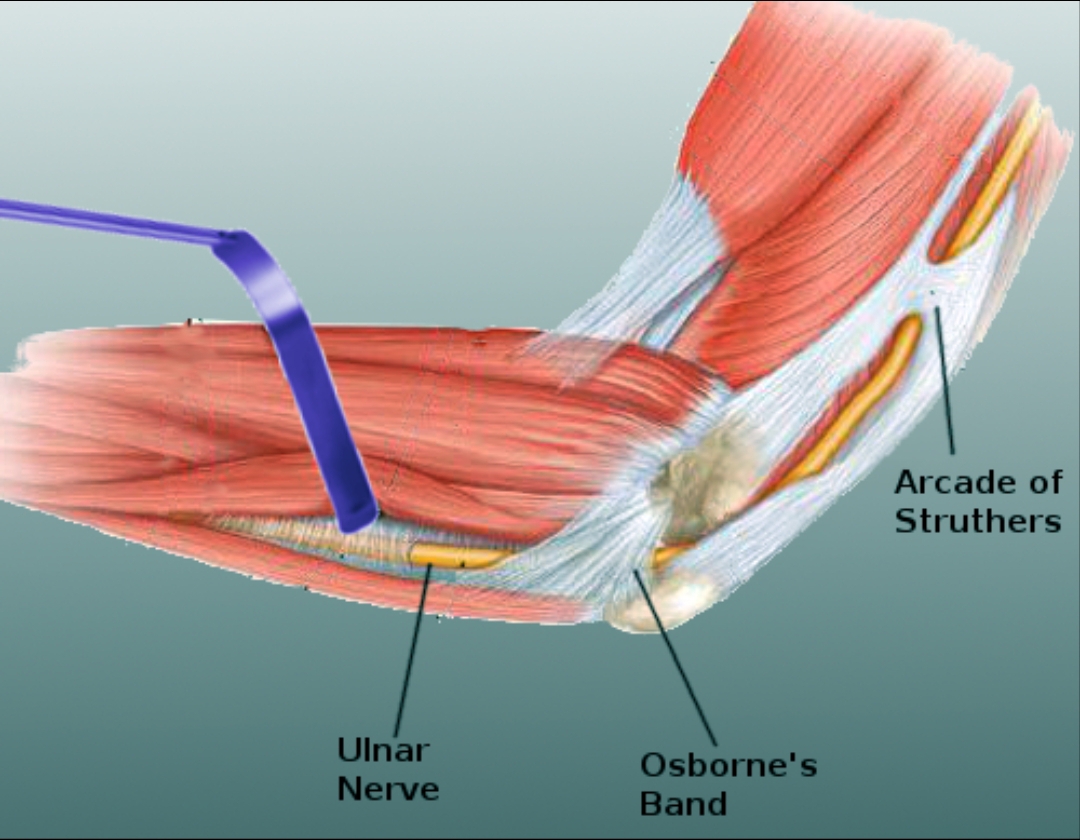

The most notable structure located on the medial aspect of the elbow is the cubital tunnel, through which the ulnar nerve passes. The walls creating the tunnel include the olecranon and the medial epicondyle, while the joint capsule of the elbow and the transverse and posterior bands of the medial ulnar collateral ligament form the floor, and finally the roof is comprised of the fascia of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and Osborne’s band, and referred to as Osborne's fascia. Due to its location and function, Osborne’s fascia is of significance predominantly due to its potential to compress the ulnar nerve in the elbow.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Osborne’s band is a fibrous band of tissue that connects the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle, thereby forming the roof of the cubital tunnel. It extends from the middle of the olecranon to the top of it and has a width span of approximately 4 mm.[1] A study showed that the length of this band and therefore the distance between the heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle is increased with elbow flexion although the degree to which the elbow must be flexed to cause these findings varies between people. Although important clinically in the pathology of certain conditions such as ulnar neuritis and Ehler’s Danlos, Osborne’s band is not a necessary tissue for functionality – various studies have revealed its congenital absence in 10-23% of subjects tested. It is not present in all individuals, with studies showing that the number of people with Osborne’s band being 77-100% of patients. It is often implicated in ulnar nerve compression and surgically transected to decompress the ulnar nerve in this area of the elbow.

Muscles

Tendons of the cubital tunnel, as well as all parts of the cubital tunnel, are visible via ultrasound of the elbow. With this technique, Osborne's band can be appreciated covering the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel. The ulnar nerve is also visible if the probe moves slightly distal to the band. At this point, the ulnar nerve can be noted lying between the two bellies of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.[2] MRI can also be used to visualize the cubital tunnel and therefore Osborne’s band with the arm either extended and supine or extended overhead and prone.[3]

Surgical Considerations

If it is the cause of ulnar entrapment, surgeons can excise the Osborne ligament to decompress the ulnar nerve. This procedure involves exposing the nerve at the elbow and noting its area of compression. At that point, a surgeon will simply cut the ligament where it lies over the nerve. In his discovery of the band of tissue, Osborne did this by making a small incision parallel to the ulnar nerve. He then replaced the fatty tissue over the nerve before closing. Experience shows that patients experience relief of sensorimotor symptoms, most notably numbness, immediately following decompression of this structure, with motor functions recovering completely by one week after the operation. A case report of a woman receiving this procedure after one year of symptoms revealed substantial recovery and regeneration of the compressed ulnar nerve as shown on control electroneuromyographic studies one month after the operation.[4]

Clinical Significance

Osborne’s band has been implicated in both tractional ulnar neuritis and ulnar entrapment leading to cubital tunnel syndrome. The band lies on the roof of the cubital tunnel, making it a prime location for compression injuries when the elbow is in flexion, as this reduces the space of the tunnel and increases the length of the band. There are four different places at which ulnar entrapment can occur. These are: the fibrous canal on the medial aspect of the arm, also known as arcade of Struthers, the fibrous canal at the wrist, also known as Guyon’s canal, the retro epicondylar groove at the elbow, and finally the aponeurosis between the muscle heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscles – Osborne’s band.[4] Traction against this aponeurosis can irritate the nerve, and the resulting ulnar neuritis, or ulnar nerve inflammation, presents clinically as numbness and tingling in the ulnar nerve distribution.[5] The volume of the cubital tunnel decreases progressively with elbow flexion, which can potentially compress the nerve against Osborne's band.[6] Compression against this band results in the aforementioned cubital tunnel syndrome which presents similarly with numbness and tingling in ulnar nerve distribution that also causes nighttime awakening.

When taking a comprehensive history of someone with ulnar nerve entrapment, the historian should seek an understanding of whether or not an injury precipitated the patient's symptoms. If so, when was the onset of injury, what measures the patient has taken to alleviate their symptoms, and most importantly, in what way has functionality been reduced due to his/her symptoms?[7] At risk are patients with a history of repetitive forceful flexion & extension of fingers, wrists, and elbow without breaks in between.[8] A physical exam test helpful in identifying Osborne’s band as the cause of ulnar nerve damage is one that is meant to assess its level of tension – the ‘scratch collapse test’. It involves having the patient maintain a 90-degree elbow flexion with hand open and fingers flexed and pointed towards the person performing the exam. The assessor then rotates the forearm medially in an attempt to determine the amount of resistance produced with this movement. The suspected area of ulnar entrapment is then ‘scratched’ or ‘stroked’ and then the test is repeated. If the resistance felt after the stroking reduces considerably in comparison to the initial resistance observed, then the patient has a positive scratch collapse test, and in theory, the assessor has located the precise area of entrapment. Using this method can implicate Osborne’s band as the cause of ulnar nerve entrapment in 80% of subjects in one prospective study.[9] Although helpful, this physical exam finding is not diagnostic due to its lack of universal acceptance.[6]

Other Issues

There are several inconsistencies in the terminology used to describe this band of tissue, and the nomenclature is in question due to these inconsistencies. It has been called Osborne’s band, Osborne’s ligament, and Osborne’s fascia. Nowhere in literature has it been referred to consistently under the same terminology. This terminology is one aspect of its story yet to be decided.[10]

Media

References

Robertson C, Saratsiotis J. A review of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2005 Jun:28(5):345 [PubMed PMID: 15965409]

De Maeseneer M, Brigido MK, Antic M, Lenchik L, Milants A, Vereecke E, Jager T, Shahabpour M. Ultrasound of the elbow with emphasis on detailed assessment of ligaments, tendons, and nerves. European journal of radiology. 2015 Apr:84(4):671-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.12.007. Epub 2014 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 25638576]

Simonson S, Lott K, Major NM. Magnetic resonance imaging of the elbow. Seminars in roentgenology. 2010 Jul:45(3):180-93. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2010.01.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20483114]

Simsek S, Er U, Demirci A, Sorar M. Operative illustrations of the Osborne's ligament. Turkish neurosurgery. 2011:21(2):269-70. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.3764-10.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21534217]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBradshaw DY, Shefner JM. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Neurologic clinics. 1999 Aug:17(3):447-61, v-vi [PubMed PMID: 10393748]

Granger A, Sardi JP, Iwanaga J, Wilson TJ, Yang L, Loukas M, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Osborne's Ligament: A Review of its History, Anatomy, and Surgical Importance. Cureus. 2017 Mar 6:9(3):e1080. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1080. Epub 2017 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 28405530]

Jie KE, van Dam LF, Verhagen TF, Hammacher ER. Extension test and ossal point tenderness cannot accurately exclude significant injury in acute elbow trauma. Annals of emergency medicine. 2014 Jul:64(1):74-8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.022. Epub 2014 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 24530106]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBonfiglioli R, Lodi V, Tabanelli S, Violante FS. [Entrapment of the ulnar nerve at the elbow caused by repetitive movements: description of a clinical case]. La Medicina del lavoro. 1996 Mar-Apr:87(2):147-51 [PubMed PMID: 8926917]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavidge KM, Gontre G, Tang D, Boyd KU, Yee A, Damiano MS, Mackinnon SE. The "hierarchical" Scratch Collapse Test for identifying multilevel ulnar nerve compression. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Sep:10(3):388-95. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9721-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26330768]

Wali AR, Gabel B, Mitwalli M, Tubbs RS, Brown JM. Clarification of Eponymous Anatomical Terminology: Structures Named After Dr Geoffrey V. Osborne That Compress the Ulnar Nerve at the Elbow. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2017 May 1:13(3):1558944717708030. doi: 10.1177/1558944717708030. Epub 2017 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 28503939]