Introduction

Head trauma can result in a skull fracture and is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in children. It is a regular presentation in the Paediatric Emergency Department (PED) and primary care. Children are more susceptible to head trauma and skull fracture than adults. A child's head size is approximately 18% of the body surface area in infancy. This decreases to roughly 9% by adulthood. Generally speaking, a child's skull is thinner and more pliable, thus providing less protection to the brain.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Causes of head injury and skull fracture can be separated into accidental and non-accidental injuries. Commonly, head injuries are caused by a fall. Other causes can include motor vehicle accidents (MVA), sports-related injuries, or other direct blows to the head. Occasionally, depressed "ping-pong" fractures can occur in newborns due to injury at birth. A non-accidental injury is important for clinicians to identify in children who present with a head injury and subsequent skull fracture. This is particularly important in the non-mobile infant. A meta-analysis of 12 studies of skull fractures in abuse has shown a skull fracture to have a positive predictive value of 20.1% in suspected or confirmed abuse cases.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Head injury is a very common presentation of PED and is the most common cause of lethal trauma in children. Fortunately, the majority (80% to 90%) of head injuries can be classified as mild. Very few injuries are life-threatening or require neurosurgical intervention. The incidence of skull fracture in children following head injury ranges from 2% to 20%, and further epidemiological study is needed for more accurate incidence and prevalence rates. A skull fracture is more common in children under the age of 2 years following head trauma. A fracture of the calvarium (skull cap) is more common than 1 at the base of the skull.[7]

Pathophysiology

The skull can be divided into the calvarium and the skull base. The calvarium consists of the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal bones. The skull base consists of the sphenoid, palatine, and maxillary bones, along with portions of the temporal and occipital bones.

Types of Skull Fracture

Linear

This is the most common simple type. It is typically in the temporal or parietal area.

Depressed

A direct blow to the head usually causes this and requires a neurosurgical opinion. A depressed skull fracture can sometimes be referred to as a ping-pong fracture.

Open

An open fracture carries a high risk of infection.

Basal

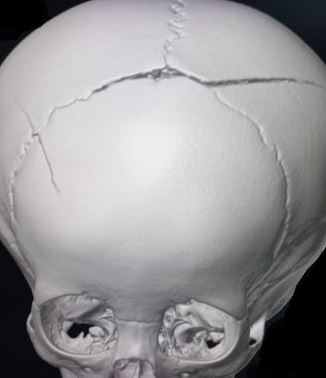

Basal fractures involve any of the bones of the base of the skull. Basal fractures are more complicated due to underlying structures such as cranial nerves and sinuses, which can lead to hearing loss, facial paralysis, or decreased sense of smell (see Image. Fracture Traversing the Superior Sagittal Sinus). They also can pose a risk for meningitis, with the most common causative organism being Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Diastatic

Diastatic fractures occur when cranial sutures are separated, most commonly with the lambdoid suture.

Growing

A growing fracture describes herniation of the brain through the broken dura following a skull fracture (often diastatic). It usually presents later and grows as the brain herniates through the gap as a persistent swelling or pulsatile mass. It is uncommon.

History and Physical

A concise history can assist the clinician when determining whether a child presenting with a head injury has a high risk of a skull fracture or traumatic brain injury.

Important Factors

- Time and presentation of injury: A delayed presentation should trigger concern and further questioning to determine if a non-accidental injury is possible.

- Mechanism of injury: Fall, drop, collision, blow to the head, or motor vehicle accident (MVA).

- Whether the event was witnessed and, if so, by whom.

- Further details about the injury: In the case of a fall, note the height of the fall and landing surface. In the case of an MVA, ask if the patient was ejected from the car or was rolled over and whether another passenger was killed, indicating a high-risk injury.

- Condition immediately after the injury: Period of lost consciousness versus immediate cry.

- Condition since the injury occurred: Alertness, eating, vomiting, seizures.

- Past medical history: Bony disorders such as osteogenesis imperfecta, bleeding disorders such as hemophilia, or if the child is on any medications.

Examination

- A trauma protocol with the primary, secondary, and tertiary survey if major trauma is suspected.

- Glasgow coma scale (GCS) is used to assess the level of alertness. However, the GCS may be less accurate in younger age groups, and a modified score should be used.

- Examination of the head to palpate for a boggy swelling (may indicate an underlying fracture), a palpable fracture line, or lacerations. Head circumference should be measured if the fontanelle is open as an increasing head circumference can indicate intracranial bleeding or swelling.

- Ear, nose, and throat examination to look for signs of basal skull fracture, including haemotympanum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or bloody otorrhoea or rhinorrhoea, Battle sign (ecchymosis on the mastoid process), raccoon eyes (periorbital ecchymosis). Ring signs can be used to assess for CSF rhinorrhoea/otorrhoea mixed with blood. When the fluid is dropped onto filter paper, the CSF separates as a ring around the blood (central blood with a clear ring around it). However, the ring sign is not specific to CSF, as blood mixed with water, saline, and other mucous also produces a ring sign.

- Neurological and cranial nerve examination, including fundoscopy, for signs of raised intracranial pressure. Cranial nerve abnormalities such as visual defect, anosmia, hearing defect, facial numbness, or paralysis can also indicate a skull base fracture.

- Head-to-toe examination assessing for bruising or other injuries in case of other traumatic injuries, or if suspicious, of non-accidental injury.

As a safeguarding procedure, the clinician always needs to carefully consider whether the described mechanism of injury is consistent with the child's developmental age and the clinical findings.

Evaluation

Skull fractures can be identified by plain radiography, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although practice varies throughout the literature, current guidance discourages using a skull radiograph and advises using a CT scan as the first-line investigation of choice if a skull fracture is suspected. In a few cases, a well, asymptomatic child with a localized head injury that is suspicious for a fracture may be a candidate for a skull x-ray instead of a CT. The risks associated with a child's CT scan should also be considered. The younger the child, the greater the risk of malignancy later in life as a result of exposure to ionizing radiation. There also are associated risks with the sedation or anesthesia that may be required to perform a CT on a child.[8][9]

Multiple clinical decision rules exist to guide clinicians when a child with a head injury requires CT: the PECARN (Paediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network) head injury algorithm, the CATCH (Canadian Assessment for Tomography of Childhood Head Injury) rule, and the CHALICE (Children's Head Injury Algorithm for prediction of Clinically Important Events) rule. Signs of skull fracture that warrant investigation with CT include signs of basal skull fracture, a palpable fracture, a swelling, bruise, or hematoma measuring greater than 5 millimeters, or suspicion of a depressed skull fracture.

Ultrasound can be used to identify skull fractures in younger patients, although it is not widely used, and further studies are needed to assess its efficacy. MRI could prove a useful investigation without radiation exposure, but its use is also limited due to its availability in the acute setting. Repeat CT imaging for patients with isolated skull fractures is not deemed necessary unless worsening clinical indicators develop. Some centers have safeguarding policies in place to guide the need for further investigation for non-accidental injury in younger children and infants with skull fractures. Routine skeletal surveys in this population with isolated skull fractures may only yield results in non-mobile infants (less than 6 months) unless there are other indications. In these children, a skull radiograph may be required in addition to a CT as it has a higher sensitivity for old fractures.

Treatment / Management

Management of skull fractures depends on the location and type of fracture along with the presence (or absence) of underlying brain injury. Most skull fractures that are simple linear fractures without underlying brain injury require no intervention. Various practice patterns exist regarding recommendations for observation periods or close outpatient follow-up. There are also variations in whether skull fractures should be treated similarly to concussions. One study has shown that most fractures requiring intervention do not necessarily require intervention for the fracture alone but rather for an associated underlying injury. Younger and symptomatic patients should be admitted to the hospital for observation. Variations to this practice are supported by multiple studies that have shown that asymptomatic children with simple fractures can be safely discharged from the emergency department. However, in each of these cases, a CT of the head had been performed to rule out an underlying brain injury.[10][11][12]

Frontal bone fractures are more likely to require neurosurgical repair. A depressed fracture usually requires intervention. Indications for a neurosurgical elevation of a depressed fracture include depression of 5 millimeters or more, dural injury, underlying hematoma, or gross contamination. An open fracture likely requires exploration and washout with antibiotic coverage. Basal skull fractures are usually managed conservatively unless there is persistent CSF leakage. A patient with a basal skull fracture should not have a nasogastric tube or nasal cannula. There is no evidence to support the role of prophylactic antibiotics in preventing meningitis, although persistent CSF leaks may increase the risk of meningitis.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for pediatric skull fractures include the following:

- Brain laceration

- Epidural hematoma

- Frontal lobe syndromes

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizures

- Hydrocephalus

- Open and depressed fracture

- Prion-related diseases

- Subdural empyema

- Subgaleal hematoma

Complications

The main complications associated with a pediatric skull fracture include:

- Seizures

- Venous sinus thrombosis

- Intracerebral bleed

- Meningitis (if there is an open fracture)

- Growing skull fracture

Consultations

Consultations that are typically requested for patients with skull fractures include the following:

- Neurosurgery

- Trauma surgery

- Neurointensivist

Pearls and Other Issues

Although head injury can lead to fatal brain injury and death, the majority of skull fractures are simple and can be managed conservatively. A head injury with a skull fracture, understandably, can generate huge parental anxiety, and clinicians need to be equipped with information to educate parents and allay fears. In addition, concerns about safeguarding and non-accidental injury should be addressed openly and professionally. When the discharge occurs directly from the emergency department, it should be in a safe environment with clear discharge instructions and return precautions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach should be considered with trauma services, neurosurgery, general pediatrics, and social work. The treatment depends on the severity of the injury and depression of the bone fragments. Close follow-up is paramount to ensure safe outcomes. Any child suspected to be a victim of nonaccidental trauma should be reported per state law. The outcomes of skull fractures depend on many factors a concomitant injury to other organs, the presence of neurological deficit at the time of presentation, low GCS, and the need for mechanical ventilation.[13][14]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Karepov Y, Kozyrev DA, Benifla M, Shapira V, Constantini S, Roth J. E-bike-related cranial injuries in pediatric population. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2019 Aug:35(8):1393-1396. doi: 10.1007/s00381-019-04146-8. Epub 2019 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 30989331]

Harsh V, Vohra V, Kumar P, Kumar J, Sahay CB, Kumar A. Elevated Skull Fractures - Too Rare to Care for, Yet too Common to Ignore. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Jan-Mar:14(1):237-239. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_242_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30937043]

Campobasso CP, De Micco F, Bugelli V, Cavezza A, Rodriguez WC 3rd, Della Pietra B. Undetected traumatic diastasis of cranial sutures: a case of child abuse. Forensic science international. 2019 May:298():307-311. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.03.011. Epub 2019 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 30925349]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoz SS,Dolachee AA,Abdali HA,Kasuya H, An enemy hides in the ceiling; pediatric traumatic brain injury caused by metallic ceiling fan: Case series and literature review. British journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Feb 18; [PubMed PMID: 30773933]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAndrew TW, Morbia R, Lorenz HP. Pediatric Facial Trauma. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2019 Apr:46(2):239-247. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.11.008. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30851755]

Donaldson K, Li X, Sartorelli KH, Weimersheimer P, Durham SR. Management of Isolated Skull Fractures in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review. Pediatric emergency care. 2019 Apr:35(4):301-308. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001814. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30855424]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePoorman GW, Segreto FA, Beaubrun BM, Jalai CM, Horn SR, Bortz CA, Diebo BG, Vira S, Bono OJ, DE LA Garza-Ramos R, Moon JY, Wang C, Hirsch BP, Tishelman JC, Zhou PL, Gerling M, Passias PG. Traumatic Fracture of the Pediatric Cervical Spine: Etiology, Epidemiology, Concurrent Injuries, and an Analysis of Perioperative Outcomes Using the Kids' Inpatient Database. International journal of spine surgery. 2019 Jan:13(1):68-78. doi: 10.14444/6009. Epub 2019 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 30805288]

Oleck NC,Dobitsch AA,Liu FC,Halsey JN,Le TT,Hoppe IC,Lee ES,Granick MS, Traumatic Falls in the Pediatric Population: Facial Fracture Patterns Observed in a Leading Cause of Childhood Injury. Annals of plastic surgery. 2019 Apr [PubMed PMID: 30730318]

Kommaraju K, Haynes JH, Ritter AM. Evaluating the Role of a Neurosurgery Consultation in Management of Pediatric Isolated Linear Skull Fractures. Pediatric neurosurgery. 2019:54(1):21-27. doi: 10.1159/000495792. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30673671]

Harvell BJ, Helmer SD, Ward JG, Ablah E, Grundmeyer R, Haan JM. Head CT Guidelines Following Concussion among the Youngest Trauma Patients: Can We Limit Radiation Exposure Following Traumatic Brain Injury? Kansas journal of medicine. 2018 May:11(2):1-17 [PubMed PMID: 29796153]

Tallapragada K, Peddada RS, Dexter M. Paediatric mild head injury: is routine admission to a tertiary trauma hospital necessary? ANZ journal of surgery. 2018 Mar:88(3):202-206. doi: 10.1111/ans.14175. Epub 2017 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 28922710]

Azim A,Jehan FS,Rhee P,O'Keeffe T,Tang A,Vercruysse G,Kulvatunyou N,Latifi R,Joseph B, Big for small: Validating brain injury guidelines in pediatric traumatic brain injury. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2017 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 28590352]

Talari HR, Hamidian Y, Moussavi N, Fakharian E, Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M, Akbari H, Taher EB. The Prognostic Value of Rotterdam Computed Tomography Score in Predicting Early Outcomes Among Children with Traumatic Brain Injury. World neurosurgery. 2019 May:125():e139-e145. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.221. Epub 2019 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 30677579]

Orru' E, Huisman TAGM, Izbudak I. Prevalence, Patterns, and Clinical Relevance of Hypoxic-Ischemic Injuries in Children Exposed to Abusive Head Trauma. Journal of neuroimaging : official journal of the American Society of Neuroimaging. 2018 Nov:28(6):608-614. doi: 10.1111/jon.12555. Epub 2018 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 30125430]