Introduction

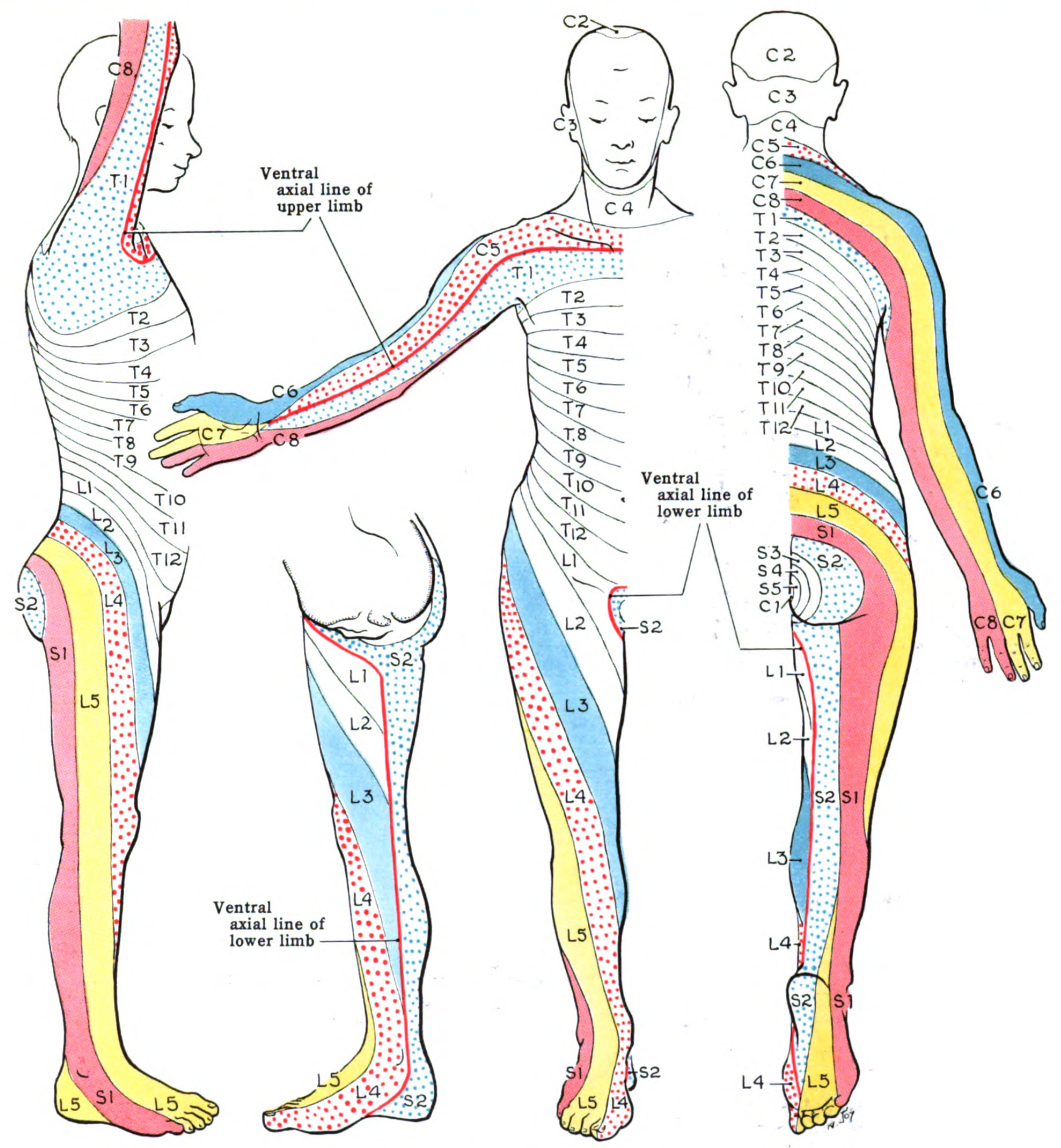

Dermatomes divide the skin according to sensory nerve distribution (see Image. Dermatome Map). One of the first to map out and discuss the dermatomes is O. Foerster in his 1933 publication entitled “The Dermatomes in Man” in the journal Brain. Some consider his work the foundation of dermatomal theory.[1] In 1948, J. Keegan and F. Garrett described spinal nerve distribution in the publication "The Segmental Distribution of the Cutaneous Nerves in the Limbs of Man,” which appeared in The Anatomical Record.[2] However, in 2008, M. Lee, R. McPhee, and M. Stringer published “An Evidence-Based Approach to Human Dermatomes” on Clinical Anatomy, which contested some classic dermatomal maps. It also proposed an evidence-based method for accurately mapping out human dermatomes.[3][4] This article focuses on dermatomes, which are essential to diagnose and manage various neurologic conditions correctly.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Spinal nerves form from the nerve roots. Dorsal nerve roots branch out from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and have a sensory function. Ventral nerve roots stem from the spinal cord's ventral horn and provide motor impulses to muscles.

The spinal nerves exit the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramina (neuroforamina), innervating various structures according to dermatomal patterns.[5]here are 31 distinct spinal segments corresponding to 31 distinct spinal nerves bilaterally. The 31 spinal nerves are broken down as follows:

- 8 pairs of cervical nerves

- 12 pairs of thoracic nerves

- 5 pairs of lumbar nerves

- 5 pairs of sacral nerves

- 1 pair of coccygeal nerves [5]

The cervical nerves C1-C7 exit through the intervertebral foramina above their respective vertebrae. Cervical nerve C8 exits between the C7 and T1 vertebrae. The remaining spinal nerves all exit below their respective vertebrae.[5]

Axial dermatomes are mostly layered horizontally. By comparison, appendicular dermatomes are arranged longitudinally. These patterns are fairly standard, although variations exist because spinal nerves' coverage areas extensively overlap.

Embryology

The spinal cord begins its development during the 3rd week of gestation with neural plate formation and neural fold elevation. Early in the 4th week, the neural folds begin to fuse. Afterward, neuroblasts form and move into the intermediate zone of the early neural tube, a process that continues throughout embryological development. In the 6th week, spinal nerves begin to form and progressively develop dorsoventrally. Dermatomal, myotomal, and scleratomal patterns form concurrently with spinal nerve elongation.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The spinal cord and spinal nerves are supplied by the anterior spinal artery and the 2 posterior spinal arteries. The anterior spinal artery provides the circulation in the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. The posterior spinal arteries cover the dorsal columns. In the skull, the spinal arteries arise from the vertebral arteries, coursing inferiorly along the spinal cord.[7]

Nerves

Several anatomic landmarks help easily identify or estimate different dermatomal levels.

- C6: Thumb

- C7: Middle finger

- C8: Little finger

- T1: Anteromedial forearm and arm

- T2: Medial forearm and arm to the axilla

- T4: Nipple

- T6: Xyphoid process

- T10: Umbilicus

- L3: Medial knee

- L4: Anterior knee and medial malleolus

- L5: Dorsal surface of the foot and first, second, and third toes

- S1: Lateral malleolus

However, detailed dermatomal maps have more applications in practice.

Clinical Significance

Sciatica

Dermatomes are valuable in localizing neurologic deficits. For example, sciatica is a neuropathy involving the sciatic nerve (L4-S3) and its associations. Symptoms like pain and tingling follow a dermatomal distribution, which, for the sciatic nerve, starts from the posterior hip and descends to the posterior aspect of the lower extremity.[8][9]

Herpesvirus Infections

Herpesviruses are neurotrophic. For example, the viral exanthem in varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection, aka chickenpox, initially has a diffuse distribution that later progresses cephalocaudally. This change gives rise to the classic "dew drops on a rose petal" pattern. The virus retreats into the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) when the acute phase of the infection resolves. Weakening of the immune system and other forms of stress can reactivate the virus.[10]

Herpes zoster virus (HZV) is essentially reactivated VZV. It causes the condition known as shingles, characterized by painful, dermatomally distributed blisters (see Image. Herpes Zoster Rash). HZV symptoms typically present in 3 phases:[11]

- Pre-eruptive or prodromal phase: sensory symptoms like pain, burning, itching, and paresthesias occur along the affected dermatomes

- Eruptive phase: vesicular (herpetiform) skin lesions erupt on the same dermatome and may progress into pustules

- Resolution phase: lesions crust and resolve

The trunk is the most commonly involved area, followed by the face.

Disseminated herpes zoster is significantly rarer and almost exclusively associated with severely immunocompromised states. Affected patients risk developing encephalitis, pneumonitis, and other life-threatening conditions.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is so named because it typically presents with eye symptoms. Herpetiform rashes, similar to other forms of shingles, can develop. However, visual impairment can result from the optic, oculomotor, or trigeminal nerve involvement.

HZO involving the trigeminal nerve (CN V) can mimic trigeminal neuralgia. The Hutchinson sign, or the formation of herpetic lesions along the lateral nose tip, indicates the involvement of the first trigeminal nerve's nasociliary branch. It often precedes ocular involvement.[12] Postherpetic neuralgia develops after the acute illness resolves and is characterized by persistent pain along the trigeminal nerve dermatomes. [11]

Other Issues

Herpes Zoster Follows a Dermatomal Distribution

Herpes zoster, aka shingles, is a common condition, with one million cases reported annually. VZV reactivation is the known cause. Triggers include advanced age, waning immunity, mental stress, and severe illness, though other factors are also thought to be in play.

For example, women are known to have stronger immunity than men. However, herpes zoster is more often reported in women than men. This is attributed to greater VZV exposure frequency and biological factors being more permissive of VZV reactivation in females than males.[13][20][21] The incidence of herpes zoster among blacks and Hispanics is lower than among whites.[14]

The condition typically manifests as a painful unilateral rash with a dermatomal distribution.[14] Occasionally, however, herpes zoster presents only with dermatomal pain but not a rash. This condition is called "herpes zoster sine herpete" (herpes zoster without the rash).

Postherpetic neuralgia is a common sequela of herpes zoster. The pain can continue long after the blisters have healed. Herpes zoster vasculitis is a potential illness complication that can result in significant morbidity and mortality.[15]

Antiviral treatment, eg, with valacyclovir, significantly shortens the eruptive phase of herpes zoster. This treatment can also minimize the risk of chronic ocular complications, but it is ineffective in preventing postherpetic neuralgia.[16]

Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is a condition that commonly involves the ophthalmic or first division of the trigeminal nerve, which innervates the cornea (see Image. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus with Hutchinson Sign). Occasionally, the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve is involved. HZO occurs in 5-10% of herpes zoster cases. [13]

Patients report that the pain associated with HZO is unlike any pain they have ever known. It has been described as itching, stinging, and resembling lightning. Some experience formication or the sensation that insects are crawling on the skin. However, the ocular manifestations of HZO are among its most serious consequences.[14] Visual impairment can result from various forms of keratitis and iritis.

Oral antiviral agents are the cornerstone of herpes zoster treatment. Mild ocular manifestations can be treated conservatively with topical corticosteroids, ophthalmic lubricants, and avoidance of toxic medications. Severe symptoms warrant aggressive measures that include tarsorropathy, amniotic membrane grafting, supraorbital or supratrochlear nerve transplantation, and corneal transplantation. The utility of recombinant nerve growth factor is under study.[14]

Postherpetic neuralgia is the most common HZO complication, occurring in 30% of HZO patients. Advanced age is a risk factor for its development. Temporal arteritis and cerebrovascular accidents may also occur as complications of this condition. HZO has been reported to be a cause of suicide in older individuals.[17]

Postherpetic Pruritus

Postherpetic itching is a potential sequela of herpes zoster. It may occur in patients who do not have postherpetic neuralgia. The condition has been reported in patients with a history of diabetes mellitus, cervical cancer, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[18] Postherpetic itching is thought to arise from the interplay of immune, neurologic, and hormonal factors.[18]

Experimental Studies: Towards the Future

The dorsal root ganglia (DRG) mediate sensation, including pain. Studies show that immunosuppression can activate DRG cells to produce nerve impulses that cause hyperalgesia. Treatment with the trial drug Tomivosertib (eFT508) inhibits the immunosuppressive kinase MNK, normalizing the DRG cells' firing rate. Washing off the drug causes the DRG cells to misfire again. This experiment can pave the way for pain mediators to become neuropathic treatments.[19]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tan TC, Black PM. The contributions of Otfrid Foerster (1873-1941) to neurology and neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2001 Nov:49(5):1231-5; discussion 1235-6 [PubMed PMID: 11846917]

KEEGAN JJ, GARRETT FD. The segmental distribution of the cutaneous nerves in the limbs of man. The Anatomical record. 1948 Dec:102(4):409-37 [PubMed PMID: 18102849]

Lee MW, McPhee RW, Stringer MD. An evidence-based approach to human dermatomes. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2008 Jul:21(5):363-73. doi: 10.1002/ca.20636. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18470936]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGreenberg SA. The history of dermatome mapping. Archives of neurology. 2003 Jan:60(1):126-31 [PubMed PMID: 12533100]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLudwig PE, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Neuroanatomy, Central Nervous System (CNS). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723039]

Elshazzly M, Lopez MJ, Reddy V, Caban O. Embryology, Central Nervous System. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252280]

Konan LM, Reddy V, Mesfin FB. Neuroanatomy, Cerebral Blood Supply. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335330]

Violante FS, Mattioli S, Bonfiglioli R. Low-back pain. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2015:131():397-410. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62627-1.00020-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26563799]

Davis D, Maini K, Vasudevan A. Sciatica. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939685]

Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes Zoster. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722854]

Kennedy PGE, Gershon AA. Clinical Features of Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection. Viruses. 2018 Nov 2:10(11):. doi: 10.3390/v10110609. Epub 2018 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 30400213]

Kedar S, Jayagopal LN, Berger JR. Neurological and Ophthalmological Manifestations of Varicella Zoster Virus. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. 2019 Jun:39(2):220-231. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000721. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30188405]

Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM, Saddier P, Nikas AA. The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database. Journal of general internal medicine. 2005 Aug:20(8):748-53 [PubMed PMID: 16050886]

Cohen EJ, Jeng BH. Herpes Zoster: A Brief Definitive Review. Cornea. 2021 Aug 1:40(8):943-949. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002754. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34029242]

Patil A, Goldust M, Wollina U. Herpes zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Viruses. 2022 Jan 19:14(2):. doi: 10.3390/v14020192. Epub 2022 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 35215786]

Servillo A, Berni A, Marchese A, Bodaghi B, Khairallah M, Read RW, Miserocchi E. Posterior Herpetic Uveitis: A Comprehensive Review. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2023 Sep:31(7):1461-1472. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2023.2221338. Epub 2023 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 37364039]

Hess TM, Lutz LJ, Nauss LA, Lamer TJ. Treatment of acute herpetic neuralgia. A case report and review of the literature. Minnesota medicine. 1990 Apr:73(4):37-40 [PubMed PMID: 2186265]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHassan S, Cohen PR. Postherpetic Pruritus: A Potential Complication of Herpes Zoster Virus Infection. Cureus. 2019 Sep 16:11(9):e5665. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5665. Epub 2019 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 31720141]

Li Y, Uhelski ML, North RY, Mwirigi JM, Tatsui CE, Cata JP, Corrales G, Price TJ, Dougherty PM. MNK inhibitor eFT508 (Tomivosertib) suppresses ectopic activity in human dorsal root ganglion neurons from dermatomes with radicular neuropathic pain. bioRxiv : the preprint server for biology. 2023 Jun 14:():. pii: 2023.06.13.544811. doi: 10.1101/2023.06.13.544811. Epub 2023 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 37398249]