Introduction

Isolated radial head dislocation is uncommon. It most commonly presents as a partial dislocation or subluxation, also known as nursemaid’s elbow, seen in children. Complete radial head dislocation, although rare, is most commonly associated with high-force injuries of the arm and, therefore, is often associated with a forearm fracture or dislocation (see Image. Radial Head Dislocation). A thorough history and physical exam, along with imaging, can aid in the appropriate evaluation and decrease the chances of complications by missed diagnosis. Although the reduction procedure is generally a straightforward process for radial head subluxation, a missed or neglected radial head dislocation will need surgical repair due to its association with ulnar fractures and other complications.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The annular ligament stabilizes the radial head. In the case of subluxation in children, an axial force on an extended, pronated forearm causes the annular ligament to slip over the radial head. On the other hand, complete radial head dislocation can occur in children and adults. Such injury is most commonly from a high-force injury causing a tear in the annular ligament. Less often, the annular ligament remains intact, connected to the lateral collateral ligament and the ulna, causing the radial head to slip under the annular ligament.

Epidemiology

Isolated radial head dislocation is rare with an unclear pathomechanism, and clinicians often miss this injury. The most common radial head dislocation is anterior and associated with multiple other injuries such as an ulnar fracture, such as a Monteggia fracture. This combination accounts for less than 2% of all forearm fractures. This fracture is rare in adults, and in children, the peak incidence is between 4 to 10 years of age. Elbow dislocations account for 10% to 25% of elbow injuries, most common between the ages of 10 to 20 years of age. Congenital radial head dislocation is also very rare. It is almost always a posterior radial head dislocation and is associated with concurrent congenital anomalies. Radial head dislocation in such patients can be bilateral and not associated with trauma. They are most often asymptomatic.

Pathophysiology

Complete radial head dislocation results from a high-force injury, such as a significant motor vehicle accident or a fall onto an outstretched arm. It is extremely rare for the radial head to become dislocated without other associated injuries. Injuries associated with a radial head dislocation, include:

- Monteggia fractures

- Elbow dislocations

- Elbow fractures

- Terrible triad injury of the elbow: fracture of the radial head, fracture of the ulnar coronoid process, and dislocation of the elbow

The head of the radius may present as congenitally dislocated in association with other congenital abnormalities such as:

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Nail-Patella syndrome

- Ulnar dysplasia

- Radioulnar synostosis

- Dyschondroplasia

History and Physical

A thorough history and description of events, whether traumatic or nontraumatic, should be obtained. The practitioner should also investigate the mechanism of injury and whether the injury involved pulling, pronation, supination, or rotational components. Any history of a congenital syndrome will play an important role. The way the patient holds the injured elbow can be helpful. On physical exam; the child with a partial displacement of the annular ligament will protectively hold their arm, commonly in an extended and pronated fashion. This type of injury causes discomfort and pain over the radial head, and the child will refuse to use their arm by holding it close to their body. There will not be any swelling, ecchymosis, or deformities other than the unwillingness of the child to use their affected arm. The patient will resist any forearm range of motion testing.

In the setting of radial head dislocation due to traumatic injury, the practitioner should pay attention to deformities, swelling, neurovascular compromise, and length discrepancies when compared to the other limb. The examiner should have a high level of suspicion when there is a restriction on the movement of a joint. Range of motion testing demonstrates restriction, particularly during flexion of the elbow with an anterior radial head dislocation. The protuberant radial head may be visible and palpable, and this abnormality is what prompts the parents to seek medical advice. Patients with congenital dislocation are generally asymptomatic until their adolescent years when they present with elbow locking or restriction of motion without any history of trauma.

Evaluation

Evaluation should include a thorough inspection, palpation, and range of motion testing of the entire affected arm. A neurologic exam is imperative. Imaging is imperative for traumatic injuries of the affected joint and the joints above and below. An x-ray is useful and quick for an acute injury. The use of ultrasound may be helpful. However, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can be adjuncts in multiple injuries.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Monteggia injury is a radial head dislocation combined with an ulnar shaft fracture. The joint will demonstrate pain and swelling, with loss of range of motion at the elbow due to radial head dislocation. Loss of extensor muscle mobility can be due to posterior interosseous nerve injury, entrapment, or stretching. Bado classification is used to distinguish four types of Monteggia fracture based on the displacement of the radial head:

- Type I: (70% of cases) Fracture of the proximal or middle third of the ulna accompanied by anterior dislocation of the radial head (most common in children/young adults)

- Type II: (15% of cases) Fracture of the proximal or middle third of the ulna with accompanying posterior dislocation of the radial head (70 to 80% of adult Monteggia fractures)

- Type III: (20% of cases) Fracture of the ulnar metaphysis (distal to coronoid process) with lateral dislocation of the radial head

- Type IV: (5% of cases) Fracture of the proximal or middle third of the ulna and radius accompanied by dislocation of the radial head in any direction

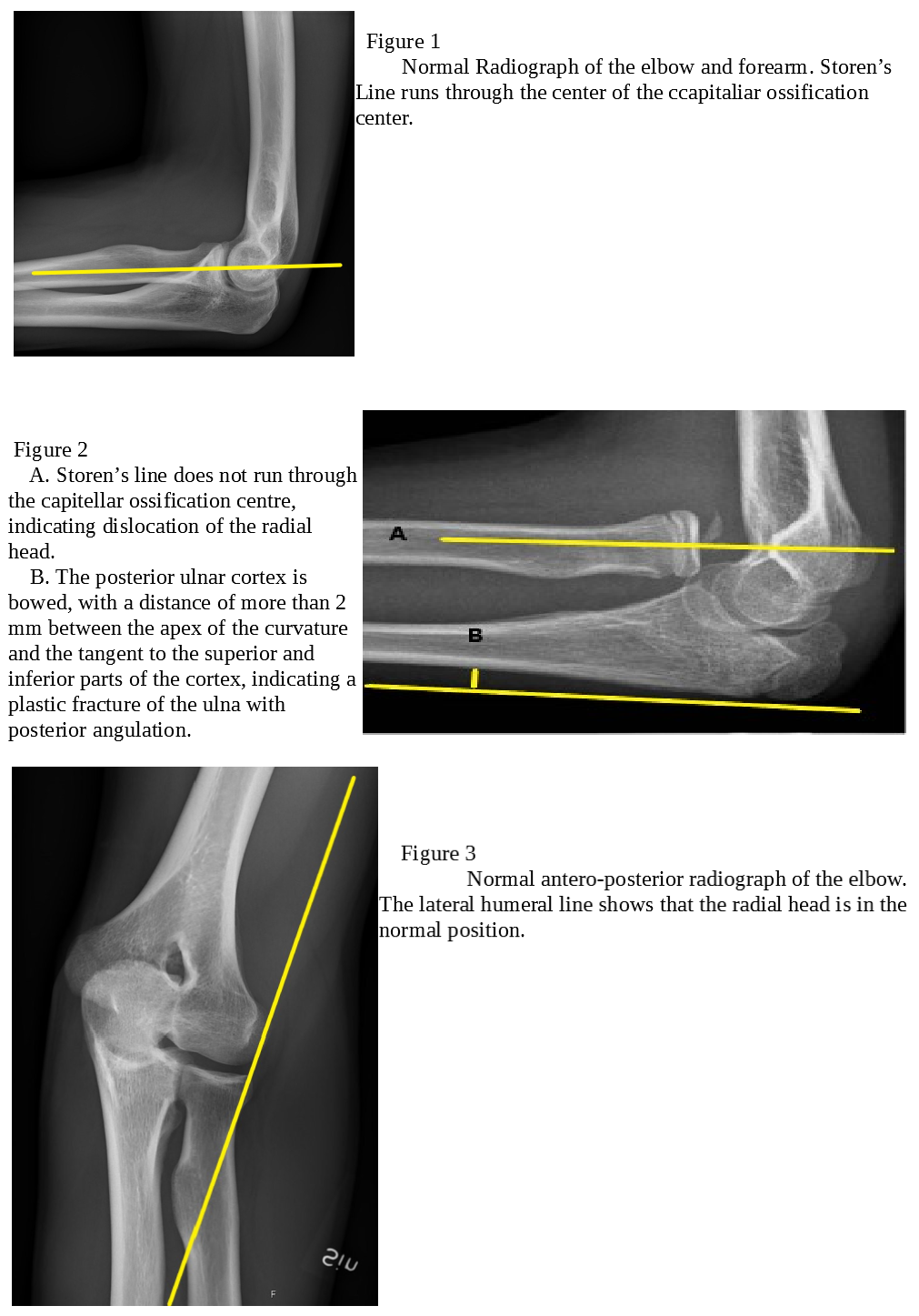

A lateral view of the elbow and drawing of the radio-capitellar line described by Storen must be done to prevent missing a radial head dislocation. The axis of the radial neck drawn on the lateral view will run through the capitellar ossification center, which signifies no radial head dislocation. Another helpful radiological tool, best viewed on the lateral view of the forearm, is the “ulnar bow sign.” Children with isolated radial head dislocation persistently had a slight curvature in the ulna on the lateral view. The posterior ulna cortex is linear, and any deviation from this line indicates a plastic fracture of the ulna.

The lateral humeral line (LHL) is often used to diagnose lateral radial head dislocation on the anterior-posterior x-ray. The LHL is a line drawn along the lateral edge of the most lateral condyle parallel to the axis of the distal shaft of the humerus. It typically intersects the lateral cortex of the radial neck. Congenital dislocations of the radial head are asymptomatic. Most commonly they will have radial head prominence and limited extension and supination of the elbow. Congenital dislocation is diagnosable on the radiological criteria described by McFarland:

- Relatively short ulna or long radius

- Hypoplastic or absent capitellum

- Partially defective trochlea

- Prominent ulnar epicondyle

- A groove in the distal radius

- Dome-shaped head of the radius with a long narrow neck

Treatment / Management

The most common radial head dislocation is anterior but based on the force, and the mechanism of injury, lateral and posterior dislocation can occur as well. The annular ligament is the chief stabilizer of the radial head and prevents radial head dislocation. Other ligaments of the proximal radioulnar joint, such as quadrate and interosseous ligament help further stabilize this joint. The treatment in the emergency setting for acute ulnar fracture with radial head dislocation up to 3 weeks after the initial injury is with sedation and closed anatomic reduction of the ulna by external maneuvers. This procedure is usually enough to reduce the radial head. Radial head stability should undergo testing with fluoroscopy after a successful reduction. Afterward, The elbow must undergo immobilization with a long arm cast with a 90-degree angle for 6 weeks. The position of the forearm during the immobilization will depend on the position associated with the greatest stability of the radius and ulna.

Children will have good outcomes with closed reduction. If there is any doubt about the stability of the reduced ulna fracture, then internal fixation is necessary. Children with irreducible and neglected/ missed anterior dislocation of the radial head will also need surgical correction. In adults, however, open surgical repair is almost always necessary. There are several surgical procedures available to address chronic radial head dislocation, but the most commonly used is an open reduction with plate and screw fixation or intramedullary nails of the ulna and annular ligament reconstruction. Congenital radial head dislocation will rarely require any intervention, until adulthood when significant pain and decreased range of motion become a concern. Radial head excision is an effective intervention in selected patients with significant elbow pain.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for nursemaid's elbow in children: fracture at the area near the elbow joint however a more distal fracture (clavicle, wrist) cannot be ruled out in young children when history is more difficult to obtain, elbow joint infection, neurological injury or even child abuse. The differential diagnosis for radial head dislocation in general: fractures of the proximal ulna and radius including radial head, fracture of the distal humerus including humeral condyle, Essex-Lopresti injury, soft tissue injury to the elbow area, bursitis, elbow joint effusion or infection, elbow joint arthritis or osteomyelitis, deep soft tissue abscess (intravenous drug abuse), neurological injury.

Prognosis

Successful reduction of a nursemaid's elbow in a child rarely will lead to long-term sequelae and the child is unlikely to experience a similar condition after the age of five when the annular ligament strengthens. The posterior interosseous nerve is in proximity to the radial head. It is the nerve most commonly injured in radial head dislocation. Its motor function is most commonly affected. Dislocations in adults often require surgical correction; prompt surgical correction may lead to arthritis and reduced range of motion; however, delayed diagnosis and correction are more likely to lead to a greater degree of morbidity. If left undiagnosed or corrected for multiple years, the radial head deformity can develop necessitating a more complex corrective surgery.

Complications

Complications of radial head dislocation include the following:

- Osteoarthritis

- Chronic pain

- Reduced mobility of the elbow joint

- Radial head deformity when the dislocation is chronically unrecognized

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The postoperative care of a dislocated elbow is similar to that of any upper extremity procedure. Opiate pain medicine is usually necessary for a short period, generally prescribed by an orthopedic surgeon. Patients are typically discharged in a splint that should be worn for several weeks before the resumption of prescribed range of motion exercises. Physical therapy after this time may speed recovery and allow for a full or almost full range of motion of the joint. Typical postoperative instructions may also include monitoring for signs of infection.

Consultations

Orthopedic consultation and close follow-up are essential in the evaluation, management, and proper treatment of radial head dislocations.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Children with prior nursemaid's elbow continue to be at risk for recurrence (not due to the injury but due to the anatomy of the annular ligament) until the annular ligament strengthens around the age of 4 or 5. Actions that may cause a nursemaid's elbow include any type of pulling on the child's arm in the axial direction, including pulling their arm through a shirt sleeve, lifting or pulling them by the arm, or catching a falling child by the arm. In young children with a prior nursemaid's elbow, these types of activities should be avoided as much as possible until the age of five.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Radial head dislocation is not an uncommon pathology seen in the emergency department. However, the key is prompt reduction; otherwise, the patient usually has a significant deformity and future arthritis. Because of its high morbidity, the disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that plays a role in the diagnosis, management, and follow-up. The emergency department physician, orthopedic nurse practitioner, or physical therapist usually performs elbow reduction. Nursemaids' elbow is common and is reducible without any sedation, and no splinting or immobilization is necessary if adequately reduced. However, follow-up is required to ensure that the reduction was successful.

Fractures and dislocations in children, although rare, will require sedation and splinting and are usually managed by an orthopedic surgeon. If unsuccessful, open surgical repair is warranted. Most adult fractures will require surgical repair. Although long-term outcomes are poor, radial head dislocation may be well tolerated for several years. Because some patients present late, clinicians must have a high level of suspicion for a radial head dislocation to prevent long-term sequelae.

In rural areas where primary care providers and nurse practitioners run outpatient and urgent clinics, it is important to refer the patient with recurrent elbow dislocation or a chronic elbow dislocation to an orthopedic surgeon promptly. The greater the delay in treatment, the worse the outcome.[12][13][14] Given that isolated radial head dislocation is uncommon, it is important that healthcare providers be able to identify signs and symptoms, and the mechanism of injury, and help provide optimal management for this injury.

The interprofessional team must work together to diagnose and treat this condition, especially since early detection significantly improves outcomes. Clinicians are often the first to encounter these patients, and they need to decide if orthopedic intervention is necessary. Nurses can assist in taking the history and triage efforts, particularly in the ED. Pharmacists may not have a direct role in initial management, but in the event that pain medication becomes part of the treatment plan, they are tasked with communicating back to the healthcare team regarding dosing and potential drug interactions and adverse effects. In post-surgical cases, the pharmacist will play a role in pain management strategies and medication reconciliation, and since surgical cases are typically adults, there is a greater need for medication reconciliation. Physical therapists will handle the bulk of the rehabilitative duties, and report back to the managing clinician regarding progress and/or setbacks. All these members of the interprofessional team need to communicate and collaborate effectively to both diagnose and manage this condition to achieve optimal outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Radial Head Dislocation. Top image: normal radiograph of the forearm; middle image: A) Soren line, B) posterior ulna cortex; and bottom image: normal anteroposterior radiograph of the forearm.

Jagadish Prabhu, Mohammed Faqi, Fahad AL Khalifa, Rashad Awad, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mikael Häggström, MD, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Wong K, Troncoso AB, Calello DP, Salo D, Fiesseler F. Radial Head Subluxation: Factors Associated with Its Recurrence and Radiographic Evaluation in a Tertiary Pediatric Emergency Department. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2016 Dec:51(6):621-627. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.07.081. Epub 2016 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 27687166]

Hill CE, Cooke S. Common Paediatric Elbow Injuries. The open orthopaedics journal. 2017:11():1380-1393. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711011380. Epub 2017 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 29290878]

Hayami N, Omokawa S, Iida A, Kraisarin J, Moritomo H, Mahakkanukrauh P, Shimizu T, Kawamura K, Tanaka Y. Biomechanical study of isolated radial head dislocation. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017 Nov 21:18(1):470. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1829-1. Epub 2017 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 29157249]

Rehim SA, Maynard MA, Sebastin SJ, Chung KC. Monteggia fracture dislocations: a historical review. The Journal of hand surgery. 2014 Jul:39(7):1384-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.02.024. Epub 2014 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 24792923]

Delpont M, Louahem D, Cottalorda J. Monteggia injuries. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2018 Feb:104(1S):S113-S120. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.04.014. Epub 2017 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 29174872]

Gupta V, Kundu Z, Sangwan S, Lamba D. Isolated post-traumatic radial head dislocation, a rare and easily missed injury-a case report. Malaysian orthopaedic journal. 2013 Mar:7(1):74-8. doi: 10.5704/MOJ.1303.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25722812]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBazzocchi A, Aparisi Gómez MP, Bartoloni A, Guglielmi G. Emergency and Trauma of the Elbow. Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 2017 Jul:21(3):257-281. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1602415. Epub 2017 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 28571089]

de Pablo Márquez B, Castillón Bernal P, Bernaus Johnson MC, Ibañez Aparicio NM. [Elbow dislocation]. Semergen. 2017 Nov-Dec:43(8):574-577. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2017.01.005. Epub 2017 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 28285907]

Li H, Cai QX, Shen PQ, Chen T, Zhang ZM, Zhao L. Posterior interosseous nerve entrapment after Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. Chinese journal of traumatology = Zhonghua chuang shang za zhi. 2013:16(3):131-5 [PubMed PMID: 23735545]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBengard MJ, Calfee RP, Steffen JA, Goldfarb CA. Intermediate-term to long-term outcome of surgically and nonsurgically treated congenital, isolated radial head dislocation. The Journal of hand surgery. 2012 Dec:37(12):2495-501. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.08.032. Epub 2012 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 23123151]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKaruppal R, Marthya A, Raman RV, Somasundaran S. Case report: congenital dislocation of the radial head -a two-in-one approach. F1000Research. 2014:3():22. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.3-22.v1. Epub 2014 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 27158442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen H, Shao Y, Li S. Replacement or repair of terrible triad of the elbow: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019 Feb:98(6):e13054. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013054. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30732120]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDomos P, Griffiths E, White A. Outcomes following surgical management of complex terrible triad injuries of the elbow: a single surgeon case series. Shoulder & elbow. 2018 Jul:10(3):216-222. doi: 10.1177/1758573217713694. Epub 2017 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 29796110]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhou C, Xu J, Lin J, Lin R, Chen K, Kong J, Feng Y, Shui X. Comparison of a single approach versus double approaches for the treatment of terrible traid of elbow-A retrospective study. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2018 Mar:51():49-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.01.012. Epub 2018 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 29367033]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence