Introduction

Inferior wall myocardial infarction occurs from a coronary artery occlusion, resulting in decreased perfusion in that region of the myocardium. Unless there is timely treatment, this results in myocardial ischemia followed by infarction. In most patients, the right coronary artery supplies the inferior myocardium. In about 6-10% of the population, the left circumflex supplies the posterior descending coronary artery because of left dominance. Approximately 40% of all myocardial infarctions involve the inferior wall. Traditionally, inferior myocardial infarctions have a better prognosis than those in other regions, such as the anterior wall of the heart. The mortality rate of an inferior wall myocardial infarction is less than 10%. However, several complicating factors increase mortality, including right ventricular infarction, hypotension, bradycardia, heart block, and cardiogenic shock.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Inferior wall myocardial infarctions are due to ischemia and infarction to the inferior region of the heart. In 80% of patients, the inferior wall of the heart is supplied by the right coronary artery via the posterior descending artery. In the other 20% of patients, the posterior descending artery is a branch of the circumflex artery.[4]

Epidemiology

There were 8.6 million myocardial infarctions in 2013 worldwide. Inferior wall myocardial infarctions are estimated to be 40% to 50% of all myocardial infarctions. They have a better prognosis than other myocardial infarctions, with a mortality of 2% to 9%. However, up to 40% of inferior wall myocardial infarctions are associated with right ventricular involvement, which results in a worse outcome.[5]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of myocardial infarction involves the rupture of a coronary artery plaque, thrombosis, and blockage of the downstream perfusion, leading to myocardial ischemia and necrosis. The culprit vessel in most patients is the right coronary artery, which feeds the posterior descending artery. This anatomy is said to be right dominant. Most patients have left dominant anatomy with the posterior coronary artery supplied from the circumflex artery. The most common ECG finding with inferior wall myocardial infarction is ST elevation in ECG leads II, III, and aVF with reciprocal ST depression in lead aVL. The right coronary artery perfuses the AV node, so bradycardias, heart blocks, and arrhythmias are associated with inferior wall myocardial infarctions.[6]

History and Physical

The history should focus on the usual investigation for acute coronary syndrome. Symptoms include chest pain, heaviness or pressure, shortness of breath, and diaphoresis with radiation to the jaw or arms. Other symptoms often include fatigue, lightheadedness, or nausea. During the physical exam, particular attention should be given to the heart rate since bradycardia and heart block may occur. Likewise, hypotension and evidence of poor perfusion should be assessed, especially if there is concomitant right ventricular infarction.

Evaluation

Early and serial ECGs are an essential part of the evaluation. ECG leads II, III, and aVF correlate with the inferior wall of the heart (see Image. ECG With Pardee Waves Indicating AMI). ST-segment elevation in those leads indicates an inferior wall STEMI. Reciprocal ST depression is often seen in lead aVL. Almost half of the inferior wall infarctions are associated with right ventricular myocardial infarctions. Right-sided ECG leads should be added to examine the right ventricle. Right-sided ECGs are performed by reversing the precordial leads to the right side of the chest in a mirror image of the traditional precordial leads. Lead V4R is particularly useful for detecting a right-sided infarction. If there is evidence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, the catheterization laboratory should be activated. If there is no ST elevation, troponin levels should be followed.[7]

Treatment / Management

Suppose there is evidence of ST elevation on the ECG. In that case, the patient should be sent for emergency cardiac angiography to the catheterization lab with a goal door-to-vessel open time of under 90 minutes. Depending on facility capability or anticipated long transport time to an interventional catheterization lab, thrombolysis should be considered. If there is evidence of right ventricular infarction, avoid nitrates and provide volume to ensure adequate preload. The right ventricle contains less myocardium than the left and depends on adequate preload to ensure adequate cardiac function. If there is damage to the right ventricle, preload reduction from nitrates could result in significant hypotension. If this occurs, resuscitation with intravenous crystalloids and possible vasopressors is needed. Other treatments include aspirin load with 162 to 325 mg, unfractionated heparin, GP IIb/IIIa antagonist, and additional P2Y12 anti-platelets such as clopidogrel.[8][9][10](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis can be quite extensive. Factors that increase the likelihood of cardiac disease include exertional pain, diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, and radiation of pain to the right arm. Other life-threatening illnesses to consider include pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pneumothorax, esophageal rupture, and cardiac tamponade. There may be atypical symptoms, especially in women and older patients, so a high suspicion is required. Since symptoms include nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, and fatigue, it is imperative to consider the cardiac causes of these symptoms and not dismiss these symptoms as gastrointestinal illnesses.

Prognosis

While inferior wall myocardial infarctions traditionally have a good prognosis, a few factors may increase mortality. Approximately 40% of inferior wall infarctions also involve the right ventricle. Right ventricular infarctions are very pre-load dependent, and nitrates may precipitate a drop in blood pressure. Adding right-sided ECG leads, especially lead V4r, aids in that diagnosis. If timely treatment does not occur, there is a risk of cardiogenic shock as more myocardial death occurs. Also, heart block and bradycardia may occur because the right coronary artery perfuses the sinoatrial node. A high-degree heart block, defined as a second or third-degree block, is seen in 19% of patients with acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. The amount of collateral circulation to the AV impacts the rate of heart blocks. If there is a concomitant disease to the other coronary arteries, collateral circulation to the AV node is reduced, and the likelihood of heart block is increased.

Complications

The complications that can manifest with inferior myocardial infarctions are as follows:

- Cardiogenic shock

- Atrioventricular block

- Need for pacing

- Ventricular fibrillation

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative considerations and rehabilitation with inferior myocardial infarctions include:

- Cardiac rehabilitation

- Lowering blood pressure

- Decreasing cholesterol and blood glucose

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

Deterrence and Patient Education

Important points of patient education for preventing or managing inferior myocardial infarctions include:

- Discontinuing smoking

- Eating healthy

- Regular exercise

Pearls and Other Issues

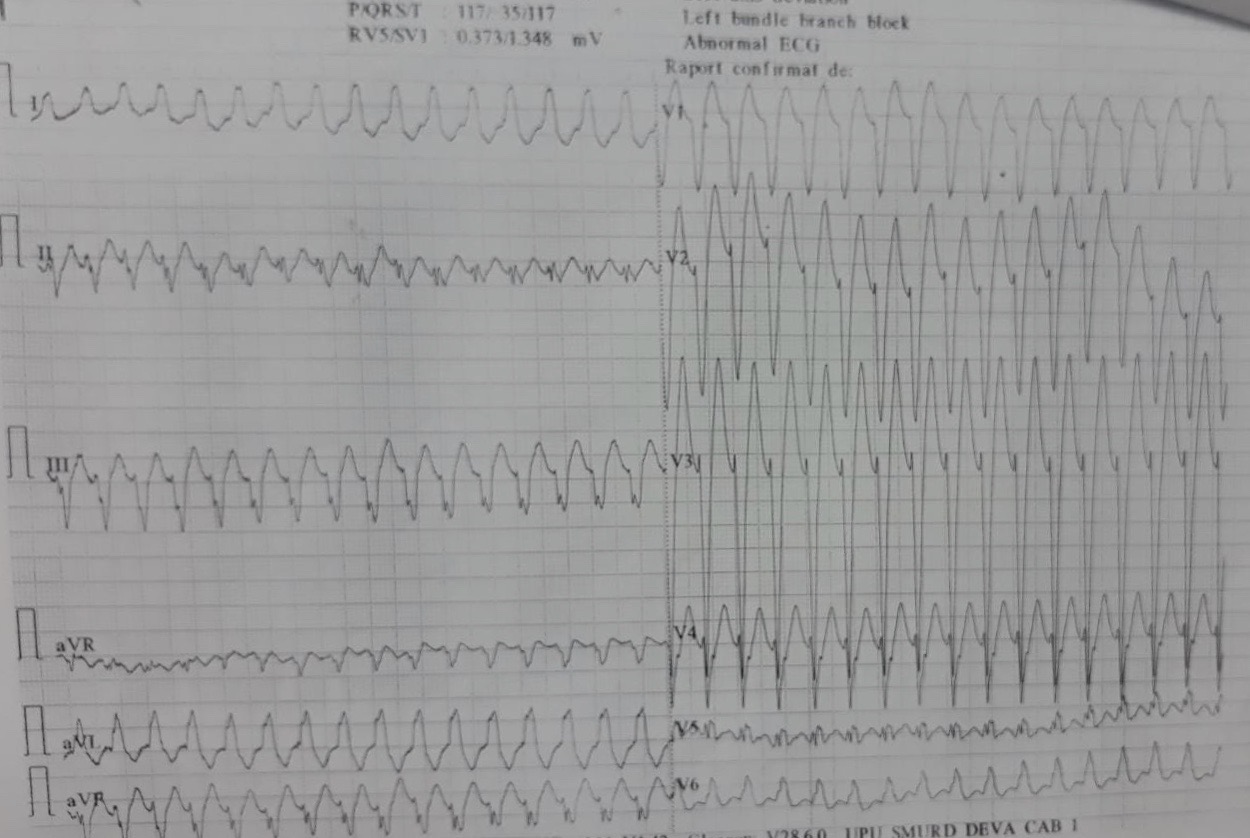

Heart blocks are present in approximately 9% of patients upon presentation, and two-thirds of patients who develop a high-degree heart block during the acute course of their inferior wall myocardial infarction do so during the first 24 hours. While heart blocks are a main contributor to morbidity and mortality, most high-degree heart blocks are treatable with atropine. It is seldom necessary to use a temporary pacemaker. The damaged myocardium can lead to potentially lethal arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation (see Image. Ischemic Ventricular Tachycardia in a Patient With an Old Inferior Myocardial Infarction). It is necessary to monitor these patients in a monitored setting, usually an intensive care unit, during the acute part of the event. When potentially lethal arrhythmias occur, early defibrillation is essential.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing an inferior wall myocardial infarction requires an interprofessional team of nurses, physicians, cardiac surgeons, and cardiologists. These patients are prone to life-threatening complications, and hence, prevention is the best approach. At discharge, the nurse should educate the patients about the potential need for pacing in the future. The dietitian should recommend a low-salt, low-fat diet. The patient should be enrolled in a cardiac rehab program. The pharmacist should encourage smoking cessation, medication compliance, and the reduction of blood cholesterol and glucose.[11][12][13]

Outcomes

When the RV is involved in an inferior wall myocardial infarction, it is an independent predictor of major complications and lengthening hospital stay. In addition, ischemia in the conducting pathways is disrupted, leading to a high degree of atrioventricular blockade that frequently requires pacing. The mortality rate when the RV is involved is often more than 25% compared to patients without RV involvement. In addition, even after discharge, many of these patients need permanent pacing within 3 years.[14][15][16]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

ECG With Pardee Waves Indicating AMI. Pardee waves indicate acute myocardial infarction in the inferior leads II, III, and aVF with reciprocal changes in the anterolateral leads.

Glenlarson, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Aydin F, Turgay Yildirim O, Dagtekin E, Huseyinoglu Aydin A, Aksit E. Acute Inferior Myocardial Infarction Caused by Lightning Strike. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2018 Dec:33(6):658-659. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X18000705. Epub 2018 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 30156178]

Lévy S. Bundle branch blocks and/or hemiblocks complicating acute myocardial ischemia or infarction. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2018 Aug:52(3):287-292. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0430-3. Epub 2018 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 30136134]

Balasubramanian K, Ramachandran B, Subramanian A, Balamurugesan K. Combined ST Elevation in a Case of Acute Myocardial Infarction: How to Identify the Infarct-related Artery? International journal of applied & basic medical research. 2018 Jul-Sep:8(3):184-186. doi: 10.4103/ijabmr.IJABMR_365_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30123751]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBouhuijzen LJ, Stoel MG. Inferior acute myocardial infarction with anterior ST-segment elevations. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2018 Oct:26(10):515-516. doi: 10.1007/s12471-018-1147-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30105594]

Aguiar Rosa S, Timóteo AT, Ferreira L, Carvalho R, Oliveira M, Cunha P, Viveiros Monteiro A, Portugal G, Almeida Morais L, Daniel P, Cruz Ferreira R. Complete atrioventricular block in acute coronary syndrome: prevalence, characterisation and implication on outcome. European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care. 2018 Apr:7(3):218-223. doi: 10.1177/2048872617716387. Epub 2017 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 28617040]

Roshdy HS, El-Dosouky II, Soliman MH. High-risk inferior myocardial infarction: Can speckle tracking predict proximal right coronary lesions? Clinical cardiology. 2018 Jan:41(1):104-110. doi: 10.1002/clc.22859. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29377172]

Albulushi A, Giannopoulos A, Kafkas N, Dragasis S, Pavlides G, Chatzizisis YS. Acute right ventricular myocardial infarction. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2018 Jul:16(7):455-464. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1489234. Epub 2018 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 29902098]

Albaghdadi A, Teleb M, Porres-Aguilar M, Porres-Munoz M, Marmol-Velez A. The dilemma of refractory hypoxemia after inferior wall myocardial infarction. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2018 Jan:31(1):67-69. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2017.1401347. Epub 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29686558]

Sibbing D, Aradi D, Jacobshagen C, Gross L, Trenk D, Geisler T, Orban M, Hadamitzky M, Merkely B, Kiss RG, Komócsi A, Dézsi CA, Holdt L, Felix SB, Parma R, Klopotowski M, Schwinger RHG, Rieber J, Huber K, Neumann FJ, Koltowski L, Mehilli J, Huczek Z, Massberg S, TROPICAL-ACS Investigators. Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): a randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Oct 14:390(10104):1747-1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32155-4. Epub 2017 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 28855078]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBahramali E, Askari A, Zakeri H, Farjam M, Dehghan A, Zendehdel K. Fasa Registry on Acute Myocardial Infarction (FaRMI): Feasibility Study and Pilot Phase Results. PloS one. 2016:11(12):e0167579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167579. Epub 2016 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 27907128]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUdroiu CA, Cotoban A, Ursulescu A, Siliste C, Vinereanu D. Interdisciplinary Approach in a Complex Case of STEMI. Maedica. 2014 Dec:9(4):382-6 [PubMed PMID: 25705309]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMartin D, Bekiaris B, Hansen G. Mobile emergency simulation training for rural health providers. Rural and remote health. 2017 Jul-Sep:17(3):4057. doi: 10.22605/RRH4057. Epub 2017 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 29040811]

Kiani F, Hesabi N, Arbabisarjou A. Assessment of Risk Factors in Patients With Myocardial Infarction. Global journal of health science. 2015 May 28:8(1):255-62. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p255. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 26234995]

Li H, Guo W, Dai W, Li L. Short-versus long-term dual antiplatelet therapy after second-generation drug-eluting stent implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug design, development and therapy. 2018:12():1815-1825. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S165435. Epub 2018 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 29970956]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGinanjar E, Yulianto Y. ST Elevation in Lead aVR and Its Association with Clinical Outcomes. Acta medica Indonesiana. 2017 Oct:49(4):347-350 [PubMed PMID: 29348386]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAltıntaş B, Yaylak B, Ede H, Altındağ R, Baysal E, Bilge Ö, Çiftçi H, Adıyaman MŞ, Karahan MZ, Kaya I, Çevik K. Impact of right ventricular diastolic dysfunction on clinical outcomes in inferior STEMI. Herz. 2019 Apr:44(2):155-160. doi: 10.1007/s00059-017-4631-9. Epub 2017 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 28993840]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence