Introduction

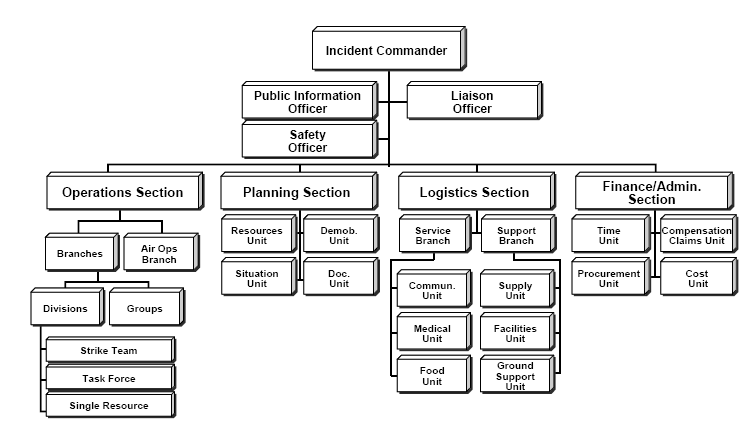

The incident command system (ICS) is a management tool for organizing and coordinating response operations during disasters and emergency responses (see Image. Incident Command System). The system allows multiple agencies to integrate crisis response efforts. The ICS is easily scalable to any size event and ensures common terminology, efficient resource use, and personnel and patient safety.

Decades of experience responding to disasters gave rise to the ICS. The current ICS developed from the work of a collaborative task force, the Firefighting Resources of Southern California Organized for Potential Emergencies (FIRESCOPE), in response to significant casualties and complications that arose from California wildfire control efforts in the 1970s.[1]

The FIRESCOPE review identified major issues with coordinating and organizing incidents. Many incident failures were due to coordination and organizational problems and resource and personnel insufficiency. Command hierarchy and accountability were lacking. Communication systems were used inefficiently and with conflicting radio codes. Freelancing—when individuals or specialized groups self-dispatched or became involved without coordinating with other responders—was a source of confusion and safety issues. The ICS intends to alleviate these problems by providing a replicable framework that responders from different regions and backgrounds can utilize.[2] Understanding the system and its components helps responding agencies coordinate their efforts.[3]

The Homeland Security Presidential Directive-5 (HSPD-5), signed by President Bush in 2003, called for the Department of Homeland Security to create a unified national ICS for coordinated response to diverse incidents at local, state, and federal levels. The result of this directive was the National Incident Management System (NIMS), a collection of best incident management practices, principles, and terminology.

One NIMS principle is standardized ICS use, which HSPD-5 requires in response to incidents.[4] Prehospital and hospital-based providers should thus be familiar with ICS terminology, basic principles, and applications.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

National Incident Management System

ICS is a fundamental NIMS component, being the national guideline for emergency incident management.[4] NIMS foundations include preparedness, communication, resource management, command and management, and ongoing maintenance, as explained below.

- “Preparedness” refers to ongoing training and education, personnel qualification assurance, potential threat identification, and interagency exercises.

- “Communication and information” describes the requirements for a standardized communication framework and emphasizes the need for a common operating picture. NIMS is based on interoperability, reliability, scalability, portability, and communications redundancy.

- “Resource management” means identifying, requesting, mobilizing, recovering, and demobilizing equipment and personnel to allow tracking, ensure safety and reimbursement, and prevent mismanagement.

- “Command and management” are responsibilities of the incident commander or unified command structure. "Command" means directing and overseeing the overall response to an incident. "Management" encompasses the various functions necessary to support incident response, such as operations, planning, logistics, finance and administration, and intelligence and information management. The ICS command structure consists of 3 principal systems: incident command, multiagency coordination, and public information.[5]

- “Ongoing maintenance” is supported by the National Integration Center and Supporting Technologies, which assists in community response planning.

HSPD-5 requires compliance with NIMS as a federal disaster preparedness assistance condition.[4] Both the original HSPD-5 and subsequent laws require ICS implementation. The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 is one example of such a law, as it requires all agencies responding to hazmat incidents to use the ICS structure. NIMS is not an operational incident management or resource allocation plan. NIMS represents a core set of doctrines, concepts, principles, terminology, and organizational processes enabling collaborative incident management.

Features of the Incident Command System

Multiple attributes were developed within the current ICS structure. Each feature is an essential ICS aspect. the ICS has 14 features, but not all will be discussed here.

Common terminology

The ICS requires communication to be in plain English, without 10 codes or other radio shortcodes, to simplify communication and prevent confusion. Similarly, all position titles and resources should have a standard name based on their capabilities, without referencing their daily titles.

When discussing an operational action, an “incident” is an unplanned situation that requires a response, such as a hazardous spill or medical incident. An “event” is a planned situation that may require emergency response or management.

Modular organization

The ICS’ size and function are based on incident complexity. The ICS expands as new objectives are delegated to include the positions needed to complete the task. For example, the operations section may add groups, divisions, or branches. Groups are units with different tasks. Divisions, such as the North and South divisions, divide an incident geographically. Branches providing additional management layers can be added to separate groups or divisions as needed. Each branch director should supervise only 3 to 7 persons.

Incident action planning

An incident action plan (IAP) is a standardized approach to identifying the objectives and responsible parties. IAPs must have 4 elements, answering the following questions:

- What do we want to do?

- Who is responsible for doing it?

- How do we communicate?

- What is the procedure if someone is injured?

IAPs can be verbal reports, but ICS form 201 may be used initially and expanded to other ICS forms as needed. The initial plan must be communicated quickly and thus may include incomplete information and require later revision. Modifications are based on situational information and detailed new objectives.

Control span

Any single person should have a control span of over 3 to 7 individuals. If an individual manages more than 7 resources, then that individual should be expanded by delegating responsibility to a new section, division, or task force.

Comprehensive resource management

Comprehensive resource management is a critical principle requiring all assets and personnel during an event to be accounted for and located. The process may include resource reimbursement. Assigned resources are those working on a field assignment under a supervisor's direction. Available resources are ready for deployment (staged) but have not been assigned to a field assignment. Out-of-service resources are not in the "available" or "assigned" categories. Resources may be "out-of-service" for various reasons, including staffing shortfalls, personnel vacation, and inoperability.

Chain and unity of command

Each participant reports to only 1 supervisor, increasing accountability and preventing responders from receiving conflicting instructions. Information flows easily down the structure and increases safety. While data can flow between persons, instructions follow a strictly top-down direction.

ICS Command Staff and Section Structure

The ICS develops in a top-down modular fashion based on an incident’s size and complexity. ICS consists of the command and general staff. The command staff is at the top of the hierarchical ICS structure, while the available team comprises the response’s functional components. The command staff includes the incident commander and public information, safety, and liaison officers.

Incident commander

The incident commander is the incident’s overall leader mainly responsible for managing the response. The incident commander approves the IAP and determines the objectives during an operational period. However, the incident commander does not decide the specific strategies for achieving the goals.

A “unified command” may form when several agencies’ representatives work together as the incident commander. For example, a firefighter and the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) chief may share the incident command responsibilities and function as one position.

Public information, safety, and liaison officers

The public information officer must coordinate event-related information communication and prepare public updates. This officer is responsible for the information flow from the branches and sections to the command staff and functional units. The safety officer is in charge of ensuring the incident personnel’s safety and well-being. The liaison officer organizes all activities between agencies and must know all resources and capabilities available for an operation.

General staff

The general staff is divided into 4 functional units: planning, operations, logistics, and finance and administration. A 5th section, intelligence and investigations, is necessary for some operations. A chief leads each general staff section. The organizational units within each section are “branches” headed by branch directors. Divisions or groups are the following subunits, led by supervisors. “Divisions” are geographically based subunits, whereas “groups” are function-based subunits.

Operations section

The operations section is responsible for all tactical activities. This section must prioritize saving lives, reducing immediate hazards, and protecting property. Divisions or groups may be separated into single resources, strike teams, and task forces. Single resources are individual units or assets deployed to accomplish specific tasks within the incident. Examples are a single fire engine, one ambulance, and an independently operating rescue team. Strike teams are composed of multiple units of the same resource type, such as multiple fire engines or ambulances. Strike team members work together under a designated leader to accomplish specific tactical objectives efficiently.

Task forces consist of diverse resources working collaboratively. Task forces are composed of different unit types, eg, fire engines combined with ambulances and rescue teams. Task forces are deployed to handle multifaceted challenges requiring various skills and equipment.

Planning section

The planning section compiles all relevant data and information. This section also disseminates information to other areas as appropriate. The planning section is typically divided into the resources, situation, demobilization, and documentation units.

Logistics section

The logistics section must supply service support requirements, such as housing, food, security, and transportation. Logistics is divided into the service and support branches. The service branch comprises the communications, medical, and food units. The supply, facilities, and ground support units compose the support branches.

Finance and administration section

The finance and administrative section handles the incident response’s budgeting and expenses. This section is likewise responsible for record-keeping and personnel time-tracking. The finance and administration section units include the time, procurement, compensation and claims, and cost units. The intelligence and investigations section collects information during an investigation.

Clinical Significance

Medical personnel may be involved in ICS at several levels. Besides conceptualizing ICS and NIMS, medical providers must participate in active training and exercises to enhance their ability to implement the system. Medical personnel may function as incident commanders, depending on the event type. However, a physician is often more valuable if filling another position.[6]

Depending on the incident's nature, physicians and EMS providers may need to act as safety officers or technical specialists. Healthcare providers may work in the operations or logistics section. Emergency physicians may benefit from mass casualty or terrorist event response training, given their background.[7] Such activity should consider standard ICS management, including detailed documentation, local resources, and protocols.

ICS Form 206, also known as the Medical Plan, is a standardized ICS document outlining medical considerations and resources during an incident response. This form is typically completed by the Medical Unit Leader or Medical Branch Director, acting as part of the planning section. Thus, the form must be accomplished by a medical specialist familiar to prehospital physicians.

Healthcare providers not directly involved in the ICS should be familiar with its structure and function to interact with involved personnel during an event. Hospital employees must also review the Hospital Incident Command System, a framework for addressing a healthcare-specific incident.[8]

The ICS system has become the national standard over the past 50 years. The ICS system is used internationally and beyond its original firefighting and emergency response objectives. This system is now used across federal organizations, including by the FDA.[9][10] Despite this progress, evidence supporting the ICS’ contribution to outcome improvement is lacking. Some also question the utility of a mandated system in providing abilities, training, and funding across such a diverse country.[11] While specifics may continue to change, the ICS remains the international standard for incident and event response.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Stambler KS, Barbera JA. The evolution of shortcomings in Incident Command System: Revisions have allowed critical management functions to atrophy. Journal of emergency management (Weston, Mass.). 2015 Nov-Dec:13(6):509-18. doi: 10.5055/jem.2015.0260. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26750813]

Cornelius AP, Kohn MD. EMS Disaster Planning And Operations. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613575]

Bajow NA, AlAssaf WI, Cluntun AA. Course in Prehospital Major Incidents Management for Health Care Providers in Saudi Arabia. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2018 Dec:33(6):587-595. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X18000791. Epub 2018 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 30261941]

Farcas A, Ko J, Chan J, Malik S, Nono L, Chiampas G. Use of Incident Command System for Disaster Preparedness: A Model for an Emergency Department COVID-19 Response. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2021 Jun:15(3):e31-e36. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.210. Epub 2020 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 32576330]

Jensen J, Thompson S. The Incident Command System: a literature review. Disasters. 2016 Jan:40(1):158-82. doi: 10.1111/disa.12135. Epub 2015 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 26271932]

Glow SD, Colucci VJ, Allington DR, Noonan CW, Hall EC. Managing multiple-casualty incidents: a rural medical preparedness training assessment. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2013 Aug:28(4):334-41. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X13000423. Epub 2013 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 23594616]

Cole LA, Natal B, Fox A, Cooper A, Kennedy CA, Connell ND, Sugalski G, Kulkarni M, Feravolo M, Lamba S. A Course on Terror Medicine: Content and Evaluations. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2016 Feb:31(1):98-101. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X15005579. Epub 2016 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 26751384]

Crabtree J. Emergency management and mass fatalities: who owns the dead? Journal of business continuity & emergency planning. 2009 Nov:4(1):33-46 [PubMed PMID: 20378492]

Kaye AD, Cornett EM, Kallurkar A, Colontonio MM, Chandler D, Mosieri C, Brondeel KC, Kikkeri S, Edinoff A, Fitz-Gerald MJ, Ghali GE, Liu H, Urman RD, Fox CJ. Framework for creating an incident command center during crises. Best practice & research. Clinical anaesthesiology. 2021 Oct:35(3):377-388. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2020.11.008. Epub 2020 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 34511226]

Seelman S, Viazis S, Merriweather SP, Cloyd TC, Aldridge M, Irvin K. Integrating the Food and Drug Administration Office of the Coordinated Outbreak Response and Evaluation Network's foodborne illness outbreak surveillance and response activities with principles of the National Incident Management System. Journal of emergency management (Weston, Mass.). 2021 Mar-Apr:19(2):131-141. doi: 10.5055/jem.0567. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33954963]

Rimstad R, Braut GS. Literature review on medical incident command. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2015 Apr:30(2):205-15. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X15000035. Epub 2015 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 25659266]