Introduction

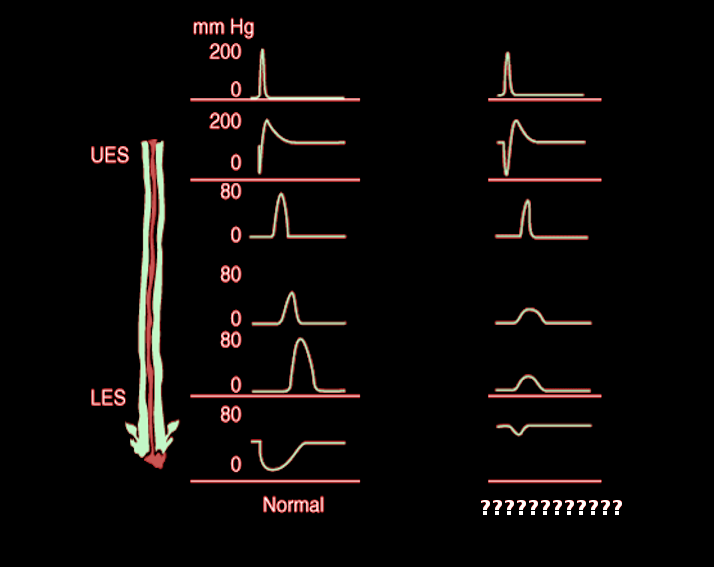

The esophagus is a muscular tube that begins at the hypopharynx and ends at the stomach. The primary role of the esophagus is to transfer solids and liquids into the stomach. There is intricate coordination of esophageal striated and smooth muscles, allowing food bolus propagation. Problems arise when patients have difficulty swallowing or reflux of gastric contents. When abnormalities of the esophagus are suspected, tests can be utilized to examine the esophagus, including upper gastrointestinal (GI) swallow study, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), pH monitoring, and esophageal manometry (see Figure. Manometry in a Patient With Chagas). This topic focuses specifically on esophageal manometry.

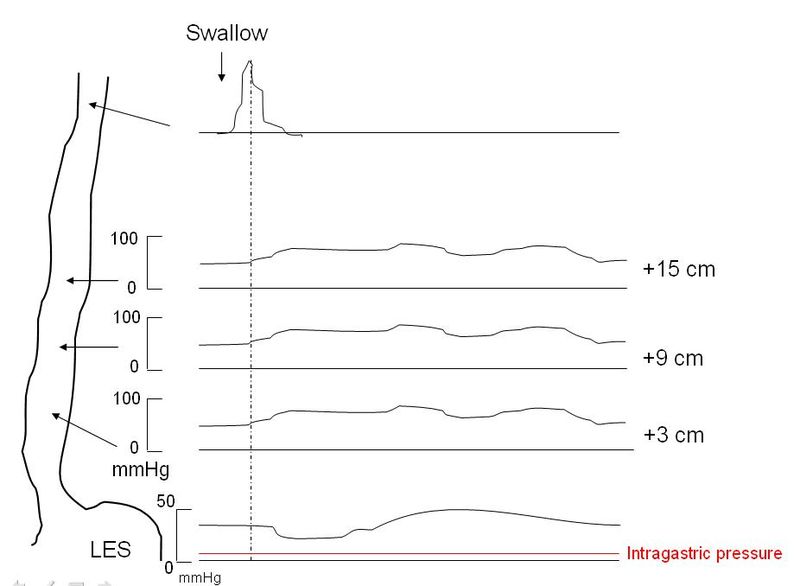

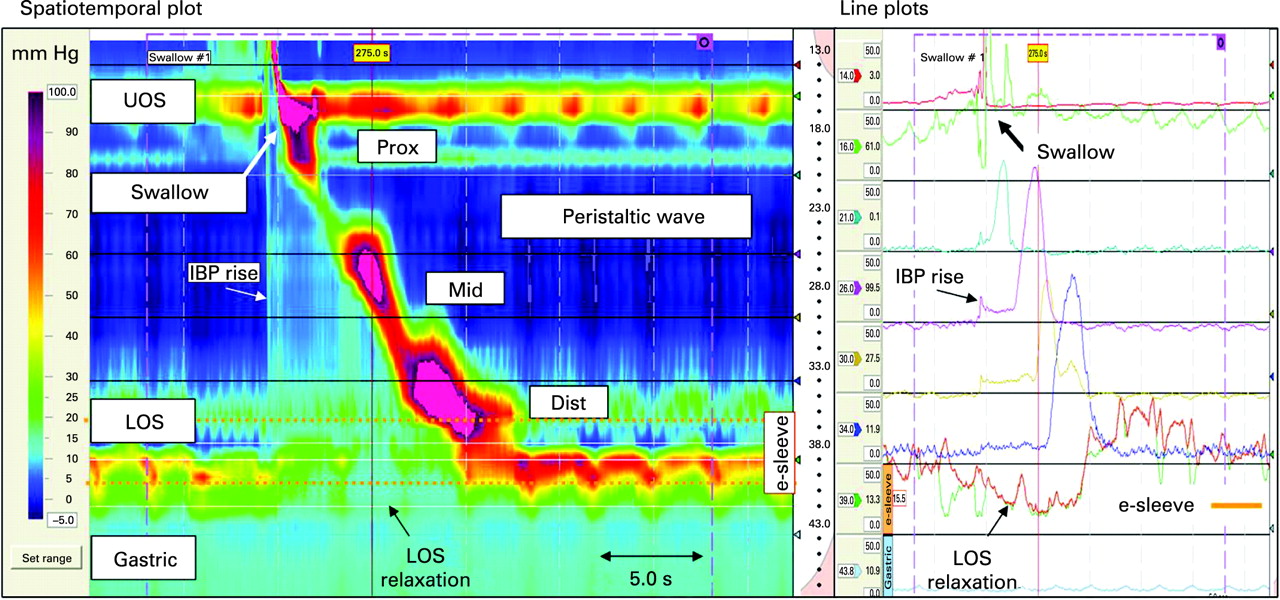

Esophageal manometry is the evaluation of the movement and pressure of the esophagus. Conventional esophageal manometry uses probes every 5 cm in the esophagus to measure contraction and pressure.[1] This was first utilized in the 1950s[1] and had been the gold standard for diagnosing esophageal motility disorders. Recently, this technology has advanced, and conventional esophageal manometry has been replaced by high-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM), which is the gold standard. (see Figure. Sample of High-Resolution Manometry). HRM uses a high-resolution catheter to transmit intraluminal pressure data that are subsequently converted into dynamic esophageal pressure topography (EPT) plots.[2] These transducer probes are located approximately every 1 cm in the esophagus on the catheter. After the catheter is placed in the esophagus, patients get a baseline measurement and then do 10 wet swallows. From this data, a motility diagnosis can be made according to the Chicago Classification (version 3.0).[3] Based on the diagnosis, different treatments can be perused.

Specimen Collection

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Specimen Collection

Patients are brought into the clinic on the day of the test. They are instructed to avoid certain medications, including calcium channel blockers, nitrates, opioids, and sedative medications, for at least 24 hours.[4] Patients should also fast for a minimum of 6 hours before the test. The throat and nose are numbed to begin the test, and the catheter is inserted into the esophagus. With up to 36 sensor probes, the HRM catheter is positioned at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and throughout the esophageal body.[4]

Procedures

The patient is then placed supine and does a baseline swallow followed by 10 swallows of water (5 mL each) with at least 30 seconds in between. During the swallow, sensors detect multiple parameters, including integrated relaxation pressure (IRP), distal contractile integer (DCI), contractile deceleration point (CDP), and the distal latency to produce color pressure topography plots, also known as Clouse plots.[3]

Adjunctive testing during HRM can provide additional information. Examples of adjunctive tests include using larger volumes of water, solid test swallows, or rapid swallows, all in the sitting position.[5][6][7] These adjunctive tests mimic normal physiologic swallows, which may induce symptoms leading to a higher diagnostic yield of HRM for esophageal motility disorders.[4]

Indications

Patients who present with symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia, gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), or noncardiac chest pain are typically worked up for esophageal pathology. Patients typically undergo an upper gastrointestinal (GI) swallow study or an EGD to rule out structural lesions or masses.[8] Once structural lesions or masses have been excluded, motility disorders of the esophagus are considered. The gold standard in evaluating esophageal motility disorders is HRM, which has replaced conventional manometry.

Potential Diagnosis

Based on the results of HRM, the patient is classified into 1 of 4 categories based on the Chicago Classification:

- Incomplete LES relaxation (achalasia or esophagogastric junction (EGJ) outflow obstruction)

- Major motility disorders (distal esophageal spasm, hypercontractile or jackhammer esophagus, and absent contractility)

- Minor motility disorders (ineffective esophageal motility or fragmented peristalsis)

- Normal esophageal motility[3][9]

Normal and Critical Findings

The first category in the Chicago Classification is incomplete LES relaxation, which includes achalasia and EGJ outflow obstruction. Achalasia is defined as the absence of esophageal peristalsis with incomplete LES relaxation. In the Chicago Classification, the diagnosis of achalasia is based on an elevated median IRP in combination with failed peristalsis or spasm. See Figure. Achalasia Manometry.[3] The IRP measures the EGJ's relaxation, with typical values (<15.0 mmHg), although this is catheter-specific.[10] During normal swallows, the LES at the EGJ relaxes to allow the food bolus into the stomach. If the LES fails to relax, this is indicated by elevated IRP. The IRP is a software mean calculation of the EGJ pressure in the lowest 4 seconds of the 10-second swallow after UES opening.[3]

If patients have an IRP greater than the upper limit of normal (ULN) along with failed peristalsis or a spasm, then they are considered to have achalasia. Achalasia is then further divided into 3 distinct subclasses based on the contractility pattern in the esophageal body. In type I (classic achalasia), no pressure waves are recorded in the distal esophagus as there is 100% failed peristalsis. Failed peristalsis is defined by DCI less than 100 mmHg cm/s for type I achalasia.[11] Type II is characterized by at least 20% pan-esophageal pressurizations with no normal peristalsis. Type II achalasia is the most prevalent subtype of achalasia.[12] These patients may have a distal latency of under 4.5 seconds, but the diagnosis of type II achalasia depends on >20% of swallows with panesophageal pressurizations.[3] In Type III, at least 20% of swallows reveal rapidly propagating or spastic simultaneous contractions with a distal latency of below 4.5 seconds and no normal peristalsis.[3][9] These spasms are typically distal on the esophageal body and do not have the pan-esophageal pressurizations seen with type II achalasia. If patients have high IRP, indicating failed LES relaxation, with weak peristalsis, or do not fit into achalasia subclasses I-III, they are considered to have EGJ outflow obstruction. EGJ outflow obstruction is largely a manometric diagnosis but has had a rising incidence since the advent of HRM.[13]

The second category of the Chicago Classification is major disorders in peristalsis, which include distal esophageal spasm, hypercontractile or jackhammer esophagus, and absent peristalsis. Distal esophageal spasm (DES) is diagnosed on HRM in patients with normal IRP and normal DCI but distal latency of less than 4.5 seconds. Distal latency is measured from the UES swallow-induced relaxation to the contractile deceleration point (CDP). Normal distal latency is greater than 4.5 seconds, and anything shorter than 4.5 seconds is considered esophageal spasm. The CDP is where peristaltic wave velocity slows, demarcating peristalsis from ampullary emptying.[3][9] The normal CDP is within 3 cm of the LES. The HRM software calculates the CDP and distal latency.

Hypercontractile or jackhammer esophagus is defined as having a distal contractile integral (DCI) of more than 8000 mmHg cm/s.[14] DCI is a multiplication of the length, duration, and amplitude of contractions. It is the force of peristalsis. A DCI less than 450 mmHg cm/s indicates weak peristalsis, whereas a DCI higher than 8000 mmHg cm/s indicates hypercontractile peristalsis.[15] Asymptomatic controls rarely have a DCI greater than 8000 mmHg cm/s, and therefore, 20% or more of swallows with a DCI of more than 8000 mmHg cm/s are required to diagnose jackhammer esophagus.[9] Patients with hypercontractile esophagus typically have normal IRP and distal latency, which excludes achalasia and distal esophageal spasm.

Absent contractility is when there is a complete failure of peristalsis with normal IRP. These patients typically have a DCI of less than 100 mmHg cm/s.[3] These patients are often diagnosed with a systemic autoimmune rheumatological disorder, such as systemic scleroderma.[16] The absent contractility also predisposes these patients to have symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. If patients have borderline elevated IRP, they may be considered to have type I achalasia.[9]

The third category of the Chicago Classification is minor peristalsis disorders, including ineffective esophageal motility or fragmented peristalsis. Ineffective esophageal motility is diagnosed when >50% of swallows are ineffective, as defined by failed (DCI <100 mmHg cm/s) or weak (DCI 100 mmHg cm/s to 450 mmHg cm/s) peristalsis.[3] These patients have normal IRP and distal latency. Fragmented peristalsis is defined as >50% of swallows with a large break (>5 cm) between peristaltic contractions and not having ineffective esophageal motility.[3]

Minor disorders of peristalsis are conditions with impaired esophageal bolus transit. The clinical validity of these manometric diagnoses has come under question. Often, patients diagnosed with minor disorders of peristalsis report minimal symptoms and have good long-term outcomes.[17] Furthermore, minor disorders of peristalsis can be seen in asymptomatic, normal control subjects, unlike major disorders of peristalsis or incomplete LES relaxation.[17] Finally, the term "nutcracker esophagus" used to be defined as DCI 5000 mmHg cm/s to 8000 mmHg cm/s.[3] However, this term is no longer used as it has little clinical significance.[3]

The fourth category of the Chicago Classification is normal esophageal manometry. These patients have normal IRP (greater than 15 mmHg), normal distal latency (more than 4.5 seconds), and DCI between 450 mmHg cm/s to 8000 mmHg cm/s. Normal esophageal manometry is typically diagnosed in the preoperative workup for gastroesophageal reflux surgery. Patients only need >50% effective swallows to be considered normal.[3]

Interfering Factors

Several factors interfere with the interpretation of HRM. Patients who undergo the procedure must stop certain medications, including H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors, calcium channel blocks, nitrates, opioids, sedative medications, and even caffeine.[4] Suppose patients have undergone previous esophageal surgeries, including gastric fundoplication, Heller myotomy, per-oral esophageal myotomy (POEM), pneumatic dilations (PD), or even botulinum injections. In that case, these may falsely alter the findings on HRM.[4] Finally, patients with large hiatal hernias or peptic strictures may have false HRM findings.[18]

Complications

Complications of HRM are rare. Placing the HRM nasogastric sensory catheter may cause discomfort in the nose or throat. During placement of the catheter, patients may experience a gagging sensation that may lead to emesis. Caution should be exercised when placing the catheter in patients who have recently had esophageal surgery or with esophageal varices. Finally, there have been rare instances of esophageal perforation in patients with severe achalasia during HRM.[19]

Patient Safety and Education

Patients should meet with their clinician before the procedure to explain the rationale and expectations during HRM. Patients and clinicians should meet after the procedure to discuss findings and treatment options and answer any questions. The procedure itself can be uncomfortable. It is important to educate the patient before the procedure on what they can expect.

Clinical Significance

Based on the findings on HRM, patients were stratified by the Chicago Classification into four different classifications of esophageal motility disorders. Individualized treatment plans for patients with different esophageal motility disorders must be implemented. These treatments include pharmacologic, endoscopic, and surgical options.

Patients with esophageal motility disorders who are older, frail, and have multiple comorbidities may best be treated by pharmacologic therapies, including calcium channel blockers and nitrates. Although the efficacy of these medications is low, they may offer some relief for non-surgical candidates.[20] Furthermore, patients with EGJ outlet obstruction or minor disorders of peristalsis may best be treated with pharmacologic therapy.[21]

Patients who are better surgical candidates but want to try non-surgical options may undergo endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin or endoscopic PD. After botulinum injections, patients initially may have symptom relief similar to endoscopic PD or surgical myotomy; however, the inhibitory toxin weakens after several months, and repeat injections as often required.[22] PDs are more durable in the long term than pharmacologic treatments. Furthermore, PD is similar to laparoscopic Heller myotomy with fundoplication (LHM) in terms of therapeutic success.[23][24] Therefore, PD is typically the initial treatment for achalasia, especially in type II achalasia.[20] Although PD is effective for patients with type I achalasia and absent contractility, patients treated with surgery have similar, more durable outcomes.[20]

LHM or POEM is the standard surgical treatment for esophageal motility disorders. Typically, patients are referred to surgery after failed PD. LHM and POEM have similar efficacy for symptom abatement after surgery, although higher rates of gastroesophageal reflux are reported after POEM.[25] LHM is better studied and more available in the general population, making it the most common operation for all esophageal motility disorders. Although all types of esophageal motility disorders can undergo surgery first, patients with achalasia type III, jackhammer esophagus, and distal esophageal spasm typically have better surgery response rates than PD.[26] Moreover, patients with spastic esophageal disorders and absent peristalsis may benefit more from POEM than LHM due to POEM allowing a longer esophageal myotomy compared to LHM.[26] Finally, surgery can be considered in all esophageal motility disorders in suitable candidates who have failed conservative treatments.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Castell DO. Emerging Technologies for Esophageal Manometry and pH Monitoring. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2008 Jun:4(6):404-6 [PubMed PMID: 21904516]

Yadlapati R. High-resolution esophageal manometry: interpretation in clinical practice. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2017 Jul:33(4):301-309. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000369. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28426462]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Smout AJ, Pandolfino JE, International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2015 Feb:27(2):160-74. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12477. Epub 2014 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 25469569]

Trudgill NJ, Sifrim D, Sweis R, Fullard M, Basu K, McCord M, Booth M, Hayman J, Boeckxstaens G, Johnston BT, Ager N, De Caestecker J. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for oesophageal manometry and oesophageal reflux monitoring. Gut. 2019 Oct:68(10):1731-1750. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318115. Epub 2019 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 31366456]

Elvevi A, Mauro A, Pugliese D, Bravi I, Tenca A, Consonni D, Conte D, Penagini R. Usefulness of low- and high-volume multiple rapid swallowing during high-resolution manometry. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2015 Feb:47(2):103-7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.10.007. Epub 2014 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 25458779]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAng D, Misselwitz B, Hollenstein M, Knowles K, Wright J, Tucker E, Sweis R, Fox M. Diagnostic yield of high-resolution manometry with a solid test meal for clinically relevant, symptomatic oesophageal motility disorders: serial diagnostic study. The lancet. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2017 Sep:2(9):654-661. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30148-6. Epub 2017 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 28684262]

Ang D, Hollenstein M, Misselwitz B, Knowles K, Wright J, Tucker E, Sweis R, Fox M. Rapid Drink Challenge in high-resolution manometry: an adjunctive test for detection of esophageal motility disorders. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2017 Jan:29(1):. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12902. Epub 2016 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 27420913]

. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 1999 Feb:116(2):452-4 [PubMed PMID: 9922327]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRohof WOA, Bredenoord AJ. Chicago Classification of Esophageal Motility Disorders: Lessons Learned. Current gastroenterology reports. 2017 Aug:19(8):37. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0576-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28730503]

Bogte A, Bredenoord AJ, Oors J, Siersema PD, Smout AJ. Normal values for esophageal high-resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2013 Sep:25(9):762-e579. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12167. Epub 2013 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 23803156]

Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Schwizer W, Smout AJ, International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2012 Mar:24 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):57-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22248109]

Lee JY, Kim N, Kim SE, Choi YJ, Kang KK, Oh DH, Kim HJ, Park KJ, Seo AY, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Lee DH. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of 3 subtypes of achalasia according to the chicago classification in a tertiary institute in Korea. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2013 Oct:19(4):485-94. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.4.485. Epub 2013 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 24199009]

Ihara E, Muta K, Fukaura K, Nakamura K. Diagnosis and Treatment Strategy of Achalasia Subtypes and Esophagogastric Junction Outflow Obstruction Based on High-Resolution Manometry. Digestion. 2017:95(1):29-35. doi: 10.1159/000452354. Epub 2017 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 28052278]

Clément M, Zhu WJ, Neshkova E, Bouin M. Jackhammer Esophagus: From Manometric Diagnosis to Clinical Presentation. Canadian journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2019:2019():5036160. doi: 10.1155/2019/5036160. Epub 2019 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 30941328]

Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Zhang Q, Jarosz A, Shah N, Kahrilas PJ. Quantifying esophageal peristalsis with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2006 May:290(5):G988-97 [PubMed PMID: 16410365]

Laique S, Singh T, Dornblaser D, Gadre A, Rangan V, Fass R, Kirby D, Chatterjee S, Gabbard S. Clinical Characteristics and Associated Systemic Diseases in Patients With Esophageal "Absent Contractility"-A Clinical Algorithm. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2019 Mar:53(3):184-190. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000989. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29356781]

Ravi K, Friesen L, Issaka R, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Normal or Minor Motor Function Abnormalities Detected by High-resolution Esophageal Manometry. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2015 Aug:13(8):1416-23. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.046. Epub 2015 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 25771245]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRoman S, Kahrilas PJ, Kia L, Luger D, Soper N, Pandolfino JE. Effects of large hiatal hernias on esophageal peristalsis. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012 Apr:147(4):352-7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22508779]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMeister V, Schulz H, Greving I, Imhoff M, Walter LD, May B. [Perforation of the esophagus after esophageal manometry]. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 1997 Nov 14:122(46):1410-4 [PubMed PMID: 9417381]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Treatments for achalasia in 2017: how to choose among them. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2017 Jul:33(4):270-276. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000365. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28426463]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePérez-Fernández MT, Santander C, Marinero A, Burgos-Santamaría D, Chavarría-Herbozo C. Characterization and follow-up of esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction detected by high resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2016 Jan:28(1):116-26. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12708. Epub 2015 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 26517978]

Wang L, Li YM, Li L. Meta-analysis of randomized and controlled treatment trials for achalasia. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2009 Nov:54(11):2303-11. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0637-8. Epub 2008 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 19107596]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Rohof WO, Smout AJ, Tack J, Zwinderman AH, Zaninotto G, Busch OR, European Achalasia Trial Investigators. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller's myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 May 12:364(19):1807-16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010502. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21561346]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoonen A, Annese V, Belmans A, Bredenoord AJ, Bruley des Varannes S, Costantini M, Dousset B, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Merla A, Smout AJ, Tack J, Zaninotto G, Busch OR, Boeckxstaens GE. Long-term results of the European achalasia trial: a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Gut. 2016 May:65(5):732-9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310602. Epub 2015 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 26614104]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFamiliari P, Gigante G, Marchese M, Boskoski I, Tringali A, Perri V, Costamagna G. Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy for Esophageal Achalasia: Outcomes of the First 100 Patients With Short-term Follow-up. Annals of surgery. 2016 Jan:263(1):82-7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000992. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25361224]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKumbhari V, Tieu AH, Onimaru M, El Zein MH, Teitelbaum EN, Ujiki MB, Gitelis ME, Modayil RJ, Hungness ES, Stavropoulos SN, Shiwaku H, Kunda R, Chiu P, Saxena P, Messallam AA, Inoue H, Khashab MA. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) vs laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) for the treatment of Type III achalasia in 75 patients: a multicenter comparative study. Endoscopy international open. 2015 Jun:3(3):E195-201. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391668. Epub 2015 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 26171430]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence