Introduction

Endometrial biopsy is frequently used to evaluate abnormal uterine bleeding. It is a relatively quick and cost-effective way to sample the endometrium to allow for direct histological evaluation of the endometrium. It is an essential skill to have as endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women. The American Cancer Society estimates there will be 65,950 new uterine cancer cases and 12,550 related deaths in 2022 [American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures, 2022]. The patient does not need to undergo more invasive procedures as endometrial biopsies have a high sensitivity and specificity for detecting endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial malignancy, equal to the diagnostic accuracy of dilatation and curettage (D&C) procedure.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

This is a list of the relevant anatomical structures for endometrial biopsy:

- Uterus corpus: the body of the uterus located in a female’s lower abdomen, between the bladder and the rectum

- Endometrium: the lining of the uterine cavity. It is a layer of glandular epithelium and stroma that changes thickness during the cycle

- Myometrium: the outer layer of the uterus; it consists mainly of smooth muscle cells

- Cervix: the cervix is the most inferior part of the uterus. The cervical canal connects the uterus to the vagina

- Vagina: a passageway that connects the cervix and the vulva (the external genitalia)

Indications

Indications for endometrial biopsy include:

- Abnormal uterine bleeding

- Evaluation for endometrial neoplasia or precancerous hyperplasia

- Surveillance of previously diagnosed endometrial hyperplasia or cancer

- Evaluation of uterine response to hormone therapy

Contraindications

Absolute Contraindications

- Pregnancy

- Acute pelvic inflammatory disease

- Acute cervical infection

- Acute vaginal infection

- Cervical cancer

- Lack of patient consent

Relative Contraindications

- Morbid obesity

- Cervical stenosis

- Clotting disorder or coagulopathy

Equipment

Equipment needed to perform endometrial biopsy includes:

- Patient labels

- Biopsy container with formalin

- Speculum

- Lubricating gel

- Sterile and non-sterile gloves

- Uterine sound

- Cervical dilators

- Single-toothed tenaculum

- Ring Forceps

- Iodine swabs

- Topical benzocaine gel (20%) or benzocaine spray

- An endometrial suction catheter (pipelle) x2

- 4x4 gauze

- Silver nitrate

Personnel

A clinician in the outpatient setting can perform this procedure independently. However, it may be prudent to have an assistant. An assistant can help with the preparation and specimen handling. While no universal guidelines exist regarding using a chaperone during the examination, and accusations of inappropriate conduct during the exam/procedure are rare, providers should consider utilizing a chaperone. The American Medical Association Opinion 1.2.4 discusses chaperones and recommends that physicians adopt a policy where patients are free to request a chaperone. The provider and their office staff should ensure that the policy is communicated to patients, and any member of the health care team can serve as a medical chaperone as long as there are clear expectations to uphold professional standards of privacy and confidentiality.

Preparation

Minimal preparation is required for this procedure. The procedure should be discussed with the patient in detail to include the procedure's risks and benefits. While written consent is not always required, informed consent must be obtained before starting the procedure. Anxiety and situational discomfort are common before and during the procedure. Pelvic exams and subsequent endometrial biopsies are among the most common anxiety-provoking medical procedures.[2]

The procedure can evoke negative physical and emotional symptoms, especially in patients with a history of sexual abuse or assault. This may cause the examination to be nearly unbearable and may deter the patient from seeking appropriate health care. If the performing provider or chaperone recognizes any patient discomfort, the provider should stop the procedure and address the patient's concerns. It is reasonable to elicit help from a therapist or social worker if it is apparent the provider must delay the procedure due to a patient's anxiety or discomfort.

Any woman of reproductive age or with the potential for pregnancy should have a documented negative pregnancy test prior to the procedure.

The patient can take an NSAID 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure to reduce the pain associated with cramping.

Prophylactic antibiotics are not necessary during endometrial sampling for the prevention of surgical site infection or bacterial endocarditis.[3]

Technique or Treatment

To begin the procedure, the patient should be undressed from the waist down and remain covered with a sheet to maintain modesty. The patient should only be uncovered as necessary for the procedure and should remain covered until properly positioned. The first part of the procedure is non-sterile. The patient is first placed in the lithotomy position, and a bimanual examination is done to determine the uterine size and position of the uterus. The speculum can now be inserted to allow for cervical visualization. Of note, if a Pap smear is necessary, this is an ideal time to obtain the appropriate samples before continuing the procedure. Once visualized, the cervix can be anesthetized and cleansed by spraying a 20 percent benzocaine spray for 5 seconds and then applying an iodine solution. At this time, it is appropriate to wash hands and don sterile gloves.

The next step is to determine the depth of the uterus, which is done with a uterine sound. The first step is to stabilize the cervix. A tenaculum is placed on the anterior lip of the cervix and allows the provider to straighten the uterocervical angle. The uterine sound is then inserted to an average depth of 6 to 10 cm within the uterus. The provider can discern that the sound is fully inserted when feeling resistance from the fundus. One common complication at this step is that the uterine sound will not pass through the internal cervical os; this can be overcome by using cervical dilators. The smallest size is inserted, followed by successively larger dilators' insertion until the sound can reach the fundus.

Once achieving adequate os dilation and determining the uterus' depth, the sampling pipelle can be inserted. The pipelle should be advanced until encountering resistance. This resistance should be at the same depth as the sounding of the uterus. Once the pipelle is in the uterine cavity, the internal piston on the catheter is fully withdrawn, creating suction at the catheter tip. This suction, accompanied by moving the tip with an in and out motion, allows for sample collection. This motion should be completed with a 360-degree twisting motion to reach all four quadrants of the endometrium. The pipelle is now removed, and the collected tissue sample is placed into a formalin solution. A second pass into the uterus can be done to ensure the collection of adequate tissue. If a second pass is made, ensure the catheter is not contaminated when being emptied of the first specimen.

Gently remove the tenaculum to complete the procedure. Most bleeding will be controllable with pressure via cotton swabs or a sponge stick. If bleeding persists, use silver nitrate sticks to cauterize the site.

Post-procedure care consists of allowing the patient to remain semi-recumbent as long as the patient deems it necessary to avoid any vasovagal reactions. While there are no established guidelines, many providers and hospital groups inform patients it is safe to bathe or shower immediately after the procedure but should refrain from sexual intercourse or placing any intravaginal device until any bleeding has stopped.

Complications

The most common side effect of an endometrial biopsy is cramping. This can be significantly reduced with the administration of pre-procedure NSAIDs. Once the procedure is completed, women may report light vaginal bleeding or spotting for several days. Less common side effects include uterine perforation, pelvic infection, and bacteremia. They are monitored by instructing the patient with strict return precautions, including returning to the office for fever, cramping for more than 48 hours, increasing pain, bleeding heavier than a normal menstrual period, or any foul-smelling discharge.

Clinical Significance

Endometrial biopsy is a safe and well-accepted method to evaluate abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding. As postmenopausal bleeding must always be investigated, this procedure becomes a valuable office-based diagnostic tool.[4] The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound released a consensus opinion, stating that either endometrial biopsy or transvaginal ultrasonography is effective as a first diagnostic step in evaluating postmenopausal bleeding.[5] Other studies have shown that an endometrial biopsy is as effective as dilation and curettage in detecting endometrial cancer.[6] Endometrial biopsy should remain a first-line diagnostic tool for abnormal uterine bleeding.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The female patient should be educated by the gynecologist, primary care provider, and gynecology nurse that endometrial biopsy is a procedure that, without debate, has clinical importance when evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding or postmenopausal bleeding. This education is part of the collaborative, interprofessional healthcare team approach to preparing for and performing this procedure. However, there is currently a debate on whether an endometrial biopsy should be used to evaluate infertility. Chronic endometritis is a bacterial infection of the endometrium that causes an increased prevalence of immune cells in the endometrium, and this change in histology can adversely affect fertility. There is a prevailing opinion that because chronic endometriosis is often asymptomatic, it can only be diagnosed through an endometrial biopsy. Therefore endometrial biopsy should be performed in the evaluation of infertility.[7] [Level 1]

However, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Choosing Wisely Campaign recommend against endometrial biopsy in evaluating infertility. They cite evidence that the endometrium's histological dating does not determine infertility, and the presence of chronic endometritis does not affect the cumulative live birth rate.[8][9] [Level 1]

For abnormal uterine bleeding, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists support recommendations that include differences in the indications for endometrial sampling in women based on age. In women younger than forty-five, an endometrial biopsy is only indicated if abnormal uterine is persistent. Endometrial biopsy should also be considered if there is a history of unopposed estrogen exposure, failed medical, or women at high risk of endometrial cancer. Any abnormal uterine bleeding in women over the age of forty-five should include an endometrial biopsy in the diagnostic workup.

There is another special subset of pre and postmenopausal women in whom the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists provide specific guidance in their recommendations for endometrial biopsy. This includes women who are on tamoxifen therapy. An endometrial biopsy should be performed for all postmenopausal patients on tamoxifen therapy who have abnormal uterine bleeding. It is common for premenopausal women to experience menstrual irregularities, most commonly amenorrhea, while taking tamoxifen. The guidelines do not suggest routine endometrial biopsy in these women. Unless there are risk factors for endometrial cancer, premenopausal women treated with tamoxifen do not require any additional screening or workup beyond routine gynecologic care.[10]

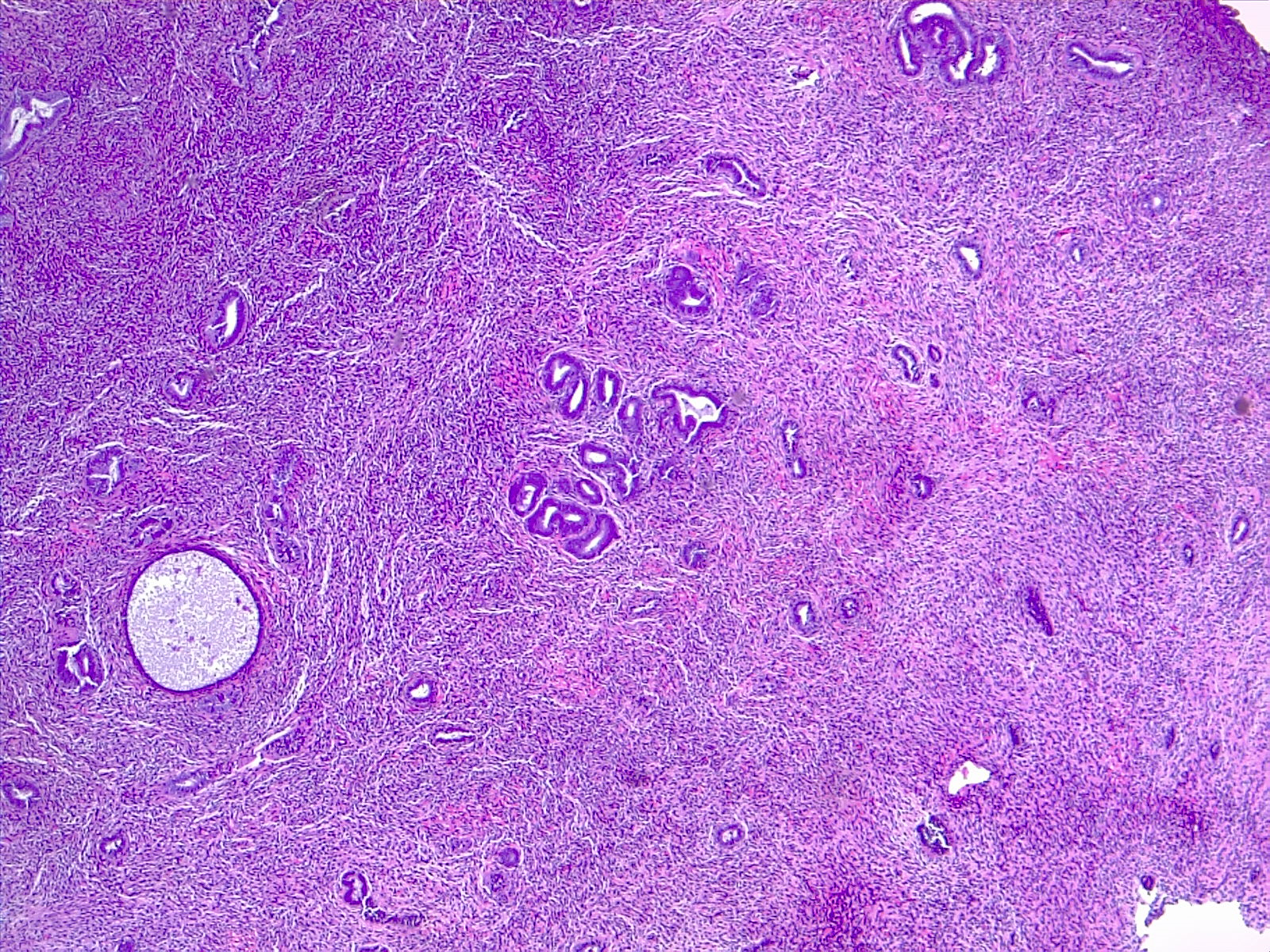

Media

References

Abdelazim IA, Aboelezz A, Abdulkareem AF. Pipelle endometrial sampling versus conventional dilatation & curettage in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association. 2013:14(1):1-5. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2013.01. Epub 2013 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 24592061]

O'Laughlin DJ, Strelow B, Fellows N, Kelsey E, Peters S, Stevens J, Tweedy J. Addressing Anxiety and Fear during the Female Pelvic Examination. Journal of primary care & community health. 2021 Jan-Dec:12():2150132721992195. doi: 10.1177/2150132721992195. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33525968]

. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 195: Prevention of Infection After Gynecologic Procedures. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:131(6):e172-e189. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002670. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29794678]

Shifren JL, Gass ML, NAMS Recommendations for Clinical Care of Midlife Women Working Group. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause (New York, N.Y.). 2014 Oct:21(10):1038-62. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000319. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25225714]

Goldstein RB, Bree RL, Benson CB, Benacerraf BR, Bloss JD, Carlos R, Fleischer AC, Goldstein SR, Hunt RB, Kurman RJ, Kurtz AB, Laing FC, Parsons AK, Smith-Bindman R, Walker J. Evaluation of the woman with postmenopausal bleeding: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound-Sponsored Consensus Conference statement. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2001 Oct:20(10):1025-36 [PubMed PMID: 11587008]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDijkhuizen FP, Mol BW, Brölmann HA, Heintz AP. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in the diagnosis of patients with endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2000 Oct 15:89(8):1765-72 [PubMed PMID: 11042572]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKimura F, Takebayashi A, Ishida M, Nakamura A, Kitazawa J, Morimune A, Hirata K, Takahashi A, Tsuji S, Takashima A, Amano T, Tsuji S, Ono T, Kaku S, Kasahara K, Moritani S, Kushima R, Murakami T. Review: Chronic endometritis and its effect on reproduction. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2019 May:45(5):951-960. doi: 10.1111/jog.13937. Epub 2019 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 30843321]

Coutifaris C, Myers ER, Guzick DS, Diamond MP, Carson SA, Legro RS, McGovern PG, Schlaff WD, Carr BR, Steinkampf MP, Silva S, Vogel DL, Leppert PC, NICHD National Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network. Histological dating of timed endometrial biopsy tissue is not related to fertility status. Fertility and sterility. 2004 Nov:82(5):1264-72 [PubMed PMID: 15533340]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKasius JC, Fatemi HM, Bourgain C, Sie-Go DM, Eijkemans RJ, Fauser BC, Devroey P, Broekmans FJ. The impact of chronic endometritis on reproductive outcome. Fertility and sterility. 2011 Dec:96(6):1451-6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.039. Epub 2011 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 22019126]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. Committee Opinion No. 601: Tamoxifen and uterine cancer. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Jun:123(6):1394-1397. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000450757.18294.cf. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24848920]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence