Introduction

The pulp is a mass of connective tissue that resides within the center of the tooth, directly beneath the layer of dentin. Referred to as part of the “dentin-pulp” complex, and also known as the endodontium, these two tissues are closely interrelated and dependent on each other’s development and survival.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure

The pulp mass is a highly vascularized and innervated mass of connective tissue that resides within a spaced called the pulp chamber. Various cell types characterize this tissue, including fibroblasts, odontoblasts, histiocytes, macrophages, mast cells, and plasma cells. It also contains an extracellular matrix composed of collagenous fibers and ground substance. Given that the pulp forms the layer of dentin evenly in every direction, it effectively shapes itself into miniaturization of the tooth and reflects the external form of the enamel.[1][2]

There are two main regions of pulpal architecture: the central and the peripheral. On the periphery of the pulp, the area adjacent to the calcified dentin exists a series of different structural layers. At the interface of the dentin-pulp complex exists a layer of columnar odontoblast cells, whose primary function is the development of dentin. Here, many dentinal tubules, channels created by the odontoblasts, extend through the dentin from the pulp to the enamel border.[3] Each one of these tubules contains an odontoblast process, a cellular extension of an odontoblast used to form the dentin, as well as dentinal fluid. Like enamel, dentin is avascular, and these tubules are crucial for providing an entryway for nutrients in the interstitial fluid that originated from capillaries in the pulp. Beneath the odontoblastic layer is the cell-free zone, or zone of Weil, an area rich in both capillaries and nerve networks. The peripheral compartment closest to the central zone is the cell-rich zone, a layer rich in fibroblasts and undifferentiated mesenchymal cell that functions in supporting the population of odontoblasts by proliferation and differentiation. This cell layer can also differentiate into fibroblasts and macrophages.[4]

The central pulp zone's perimeter is outlined by the edge of the cell-rich layer. This body of tissue is the main support system for the peripheral region and contains large vessels and nerves that extend out into the periphery. Similar to the cell-rich zones, it also contains many fibroblasts.

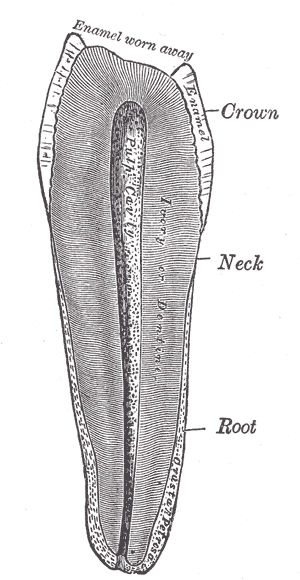

The pulp's location also affects its classification, either within the crown, coronal pulp, or the area between the cervix of the tooth to its apex, radicular pulp. Within the coronal pulp are "pulp horns," extensions of pulp that protrude into the cusps of the tooth.

Function

Put simply, the main four functions of the pulp are formation and nutrition of the dentin, as well as the innervation and defense of the tooth. Dentin formation is one of the most critical roles carried out by the pulp and, as mentioned, is formed by the odontoblasts. The pulp also plays a nutritive role in supporting the dentin with moisture and nutrients such as albumin, transferrin, tenascin, and other proteoglycans.

The defensive role of the pulp occurs through the development of new dentin, which can provide a barrier between irritants and slow the rate of carious decay. This process is mediated by the pulp, which spurs odontoblasts into action or initiates the production of new ones to form this needed hard tissue. The type and amount of dentin produced depend on numerous factors, including the source of damage (pathogen, thermal, chemical), the depth of damage, its severity, and the amount of surface area involved. The fact odontoblasts underline the significance of the pulp in dentin formation do not participate in cell division. Consequently, the formation of additional dentin relies on the pool of undifferentiated mesenchymal populations in the cell-rich zone to replace them.[5]

Embryology

To understand dental pulp development, it is best to view it through the lens of general tooth development. The initiation and progression of the tooth, and therefore pulpal, development is dependent on bidirectional cell signaling between the oral epithelium and surrounding mesenchyme. Teeth develop from two types of cells, oral epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells, which eventually form the enamel organ and dental papilla, respectively.

The development of the pulp occurs in three stages: the bud, cap, and bell stage of development. In the bud stage, epithelial cells of the dental lamina, a band of epithelial cells protruding from the oral epithelium, proliferate and produce a bud-like projection into adjacent ectomesenchyme. This rounded epithelial bud gradually enlarges and forms a concave surface, marking the cap stage. At this point, the oral epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells have now become the enamel organ and dental papilla, respectively. Lastly, the bell stage takes place, in which morphodifferentiation and histodifferentiation of the pulp occur. Here, cells in the periphery differentiate into odontoblasts, secrete predentin, a collagenous matrix that mineralizes to become dentin, as they develop their columnar shape.[6]

The dental papilla, which eventually becomes the pulp, is characterized by a milieu of densely packed cells even in the early bud stage and is comprised mostly of fibroblasts. Blood vessels and their associated nerve fibers are established early in the papilla, offering nutrition to the growing organ. While the vessels' location is in the central zone at the beginning of development, smaller capillaries eventually make their way to the periphery and offer a source of nutrients to the elongating odontoblasts. The formation of dentin by odontoblasts around the central region marks the marks point at which the dental papilla is the pulp.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the pulp arises from arterioles that make their way from the periodontium into the pulp via the apical foramen and through the radicular pulp. Each pulp chamber contains 1 to 2 arterioles and one large venule that branches into an extensive capillary network in the periphery of the crown. The network generally occupies the area under the odontoblast layer, sometimes even reaches into it. Despite the tissue pressure in the pulp being higher than other bodily tissues, the blood flow within the capillaries is comparatively higher. It causes a bulk flow of fluid across the capillaries into the tissue. As a result, fluid exits through lymphatic vessels at an equal rate to maintain a constant tissue fluid volume. Moreover, the high tissue pressure of the pulp facilitates outflow through the dentinal tubules, which functions to wash away toxins and bacteria.[8]

Nerves

There are two main types of nerves found in the pulp: autonomic and afferent fibers. Sympathetic autonomic nerve fibers found in the pulp originate in the superior cervical ganglion, located superior to the carotid artery. The axonal projections of these unmyelinated neurons innervate the smooth muscle cells of arterioles within the pulp to regulate the contractile forces that support blood flow. The other set of nerves, afferent sensory fibers, originate from the maxillary and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve. In contrast to the autonomic nerves of the pulp, these afferent sensory neurons are mostly myelinated, save for their free end terminals, and function in thermal and mechanical nociception. The myelinated portion of these fibers branches extensively beneath the cell-rich zone to form a region called the plexus of Raschkow, while the free nerve terminals extend through the cell-free zone to end up near odontoblasts, sometimes projecting out as far as the dentinal tubules.[9][10]

Physiologic Variants

The physiology of the pulp can change over time due to the aging process, resulting in distinct phenotypic differences. Compromised circulation and innervation occurs due to increased deposition of secondary dentin at the apical root, constricting the apical foramen. Blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves entering aged pulp demonstrate arteriosclerotic changes, degenerative changes, and progressive mineralization of the nerve sheath, respectively. The nerve death that occurs in aged pulp explains why aged teeth are frequently painless. Remaining odontoblasts become smaller and have a flattened morphology. Despite there being a profound reduction in cell density (about half from 20 to 70 years old), another characteristic of aged pulp is an increase in fibrosis and collagenous fibers. Due to the reduction in fibroblasts, this apparent increase is not due to increased production of collagenous fibers, but rather reflects the sheaths of connective tissue that remain after the death of nerves and blood vessels to become part of the fibrous matrix.[11][12]

Surgical Considerations

Recent studies show that the possibility to regenerate the dental pulp exists, through transplantation of dental pulp stem cells with pulpitis, on a human model.

Clinical Significance

In exchange for creating the dentin and supplying it with nutrients, the dentin’s encapsulation of the pulp provides a formidable barrier that protects it from the microbial rich oral environment. Nevertheless, the pulp is not impregnable, and the inflammation that results from its perturbation is called pulpitis.[13]

There are two variations of pulpitis: reversible and irreversible. Reversible pulpitis is characterized by mild to moderate inflammation that recedes with the management of the cause of injury. Frequent causes of reversible pulpitis include bacterial infection from caries, acute trauma, repetitive trauma from bruxism, thermal shock, excessive dehydration of a cavity during restoration, and even irritation of exposed dentin. Unlike reversible pulpitis, irreversible pulpitis has only one cause, specifically, compromise of the pulp by bacterial infection beyond the point of no return where healing is not possible.[13]

Many methods can help to discriminate between reversible and irreversible pulpitis. Sensibility tests leverage the innervation of the pulp to assess pulpal health by examining the sensory response of a tooth to an outside stimulus. One common example is a cold test, in which a cold stimulus, such as a cotton pellet cooled with dry ice, is applied to the tooth in question. In a healthy tooth, a mild response should occur that persists for no longer than 1 to 2 seconds after removal of the stimulus.[14] The same stimulus applied to a severely and irreversibly inflamed tooth results in pain that are significantly sharper, lingering for more than 30 seconds after removal of the stimulus. Other sensibility tests include mechanical ones, such as tapping the crown of the tooth or asking the patient to bite on something hard, and electric pulp testing, which measures the ability of neurons innervating the pulp to generate an action potential.[15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Yu C, Abbott PV. An overview of the dental pulp: its functions and responses to injury. Australian dental journal. 2007 Mar:52(1 Suppl):S4-16 [PubMed PMID: 17546858]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGREEN D. Morphology of the pulp cavity of the permanent teeth. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1955 Jul:8(7):743-59 [PubMed PMID: 14394660]

Yoshida S, Ohshima H. Distribution and organization of peripheral capillaries in dental pulp and their relationship to odontoblasts. The Anatomical record. 1996 Jun:245(2):313-26 [PubMed PMID: 8769670]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShi S,Gronthos S, Perivascular niche of postnatal mesenchymal stem cells in human bone marrow and dental pulp. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2003 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 12674330]

Slavkin HC. The nature and nurture of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during tooth morphogenesis. Journal de biologie buccale. 1978 Sep:6(3):189-204 [PubMed PMID: 282288]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMacNeil RL, Thomas HF. Development of the murine periodontium. I. Role of basement membrane in formation of a mineralized tissue on the developing root dentin surface. Journal of periodontology. 1993 Feb:64(2):95-102 [PubMed PMID: 8433258]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFanali S, Rametta D, Di Vincenzo F. [The embryological development of the nerve fibers of the tooth. An analysis of their formation and development correlated with the different evolutionary stages of the dental structures]. Minerva stomatologica. 1991 May:40(5):309-18 [PubMed PMID: 1944042]

Tønder KJ. Blood flow and vascular pressure in the dental pulp. Summary. Acta odontologica Scandinavica. 1980:38(3):135-44 [PubMed PMID: 6998253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceByers MR, Närhi MV, Mecifi KB. Acute and chronic reactions of dental sensory nerve fibers to cavities and desiccation in rat molars. The Anatomical record. 1988 Aug:221(4):872-83 [PubMed PMID: 3189878]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDahl E, Mjör IA. The structure and distribution of nerves in the pulp-dentin organ. Acta odontologica Scandinavica. 1973 Dec:31(6):349-56 [PubMed PMID: 4520984]

Carvalho TS, Lussi A. Age-related morphological, histological and functional changes in teeth. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2017 Apr:44(4):291-298. doi: 10.1111/joor.12474. Epub 2017 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 28032898]

Morse DR. Age-related changes of the dental pulp complex and their relationship to systemic aging. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1991 Dec:72(6):721-45 [PubMed PMID: 1812456]

Peng C, Zhao Y, Wang W, Yang Y, Qin M, Ge L. Histologic Findings of a Human Immature Revascularized/Regenerated Tooth with Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis. Journal of endodontics. 2017 Jun:43(6):905-909. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.01.031. Epub 2017 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 28416306]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMainkar A, Kim SG. Diagnostic Accuracy of 5 Dental Pulp Tests: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of endodontics. 2018 May:44(5):694-702. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.01.021. Epub 2018 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 29571914]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNissan R, Trope M, Zhang CD, Chance B. Dual wavelength spectrophotometry as a diagnostic test of the pulp chamber contents. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1992 Oct:74(4):508-14 [PubMed PMID: 1408029]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence