Introduction

Choking, or foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO), is a common and serious issue with significant morbidity and mortality. Choking can result from both food and non-food items, leading to varying degrees of asphyxiation or oxygen deprivation. FBAO is particularly prevalent among young children and people of advanced age. Many choking incidents do not result in emergency room visits or fatalities and thus go unreported. Choking on nonfood items is less frequent but predominantly affects young children. Major risk factors for choking include neurological disorders, dysphagia, and dental problems such as having few or no teeth, unstable prostheses, or unsuitable orthodontic appliances.[1]

According to the National Safety Council’s statistics, FBAO is the 4th leading cause of unintentional death, with 5051 documented fatalities in 2015. FBAO is a leading cause of accidental deaths in children younger than 16.[2] All persons, including those outside of the health field, should have a basic understanding of how to care for a choking victim due to the prevalence and rapidity of unconsciousness and death from this condition. Simple maneuvers taught to laypeople, such as the Heimlich maneuver, have been proven to save lives.[3] Complete FBAO is immediately life-threatening, while partial FBAO can hinder gas exchange and result in dyspnea, pneumonia, and abscess formation.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Choking is essentially respiratory difficulty due to a foreign body obstructing the airway.[5] Humans possess mechanisms that protect them from this condition. However, such mechanisms may be insufficient in adults with neuromuscular impairment or children with narrow airways. Glottal closure and the expiration reflex, a forced expiratory effort to eject laryngeal debris, are the body's primary mechanisms for preventing foreign bodies from entering the airway.[6] The expiration reflex differs from the cough reflex as the expiration reflex starts with expiration, while the cough reflex starts with inspiration, implying different sensory or afferent inputs and central nervous processing. The expiration reflex prevents material aspiration into the lower airways, while the cough reflex draws air into the lungs to promote a more efficient expulsion of mucus and airway debris.[7]

Understanding the differences between the cough and expiration reflex is crucial from a pharmacological perspective, as codeine, for example, does not affect the expiration reflex in doses that inhibit cough. Conversely, many anesthesia types can depress the expiration reflex more than cough.[8] Several factors make children especially prone to choking. A child’s airway is much smaller than that of an adult. Since air resistance is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the airway's cross-sectional radius (Poiseuille law), a small object can drastically affect a child’s breathing ability. Children do not generate the same force when coughing as adults, so their efforts may not be enough to dislodge a foreign body. Children commonly put objects in their mouths, starting in infancy when they begin to explore their environment.

Round foods are more likely to cause fatal choking in children, with hotdogs being the most common, followed by candy, nuts, and grapes.[9] Among non-food items, latex balloons are reportedly the leading cause of fatal choking events among children.[10] Latex balloons can conform to the airway, forming a tight seal, making them particularly dangerous to children. In adults, autopsy results from 200 choking victims showed meat, fish, and sausage to be responsible for death in 71% of cases, followed by bread and bread products (12%) and fruits and vegetables (7%).[11]

Epidemiology

The incidence of nonfatal choking episodes is difficult to measure because many of these events are transient and do not result in hospital visits. Food is the most common precipitant among children who receive treatment for nonfatal choking, responsible for 59.5% of cases, followed by non-food items, such as coins, marbles, balloons, and paper, with 31.4%. The cause is unknown in 9.1% of cases. Choking rates are highest among infants younger than 1 year, and over 75% of choking incidents occur in children younger than 3 years. No significant difference is apparent in the choking rates between boys and girls.[12]

Among adults, conditions associated with a higher risk of choking include Alzheimer disease, parkinsonism, prior stroke, intellectual or developmental disability, poor dentition, intoxication, dysphagia along with psychotropic medications, and advanced age. Researchers observed no significant difference in choking rates between men and women.[13] The estimated rates of fatal choking in adults are 0.1 per 100,000 in people between 18 and 64 years and 0.7 per 100,000 in individuals older than 65.

Previous studies have demonstrated a clear link between the duration of airway obstruction and outcomes in patients with FBAO. However, the impact of bystander intervention on FBAO patient outcomes has not been extensively examined. Research findings indicate that bystander efforts significantly correlate with improved patient outcomes, mirroring results from studies on the effects of bystander actions in cardiac arrest cases. Regrettably, similar to cardiac arrest scenarios, many individuals who have had FBAO do not receive assistance from bystanders. Research on cardiac arrest has highlighted barriers to bystander intervention, including physical and emotional challenges, as well as a lack of the necessary knowledge to perform life-saving techniques.[14]

Pathophysiology

The airway may be obstructed at any point between the pharynx and the bronchi. Obstruction in the larynx, above the vocal cords, has a better prognosis, as therapeutic maneuvers tend to be more effective than when the obstruction occurs below the larynx, which often necessitates removal by instrumentation. The degree of obstruction is also crucial, as a partial obstruction will still allow air passage and may provide additional time before the patient becomes hypoxic.

Spasms and edema result from airway obstruction and worsen over time. As time passes, the patient's efforts to expel the object diminish, reducing the likelihood of spontaneous expulsion. While impossible to control, the amount of air trapped in the lungs during complete obstruction will affect the pressure produced by therapeutic measures, such as abdominal thrusts, to remove the object.[15]

Stridor, a variably high-pitched respiratory sound, is a common physical examination finding in airway obstruction. The cause is a rapid, turbulent flow through a narrow airway opening. The reduction of airflow increases the energy expended to move air across the airway, resulting in turbulent airflow and, subsequently, stridor and respiratory distress.[16] Stridor is typically heard on inspiration. However, severe obstruction may cause biphasic stridor, occurring during both inspiration and expiration due to fixed blockage at the glottis, subglottis, or upper trachea.[17]

History and Physical

The approach for individuals who are choking is an assessment of the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC). The clinician should focus on skin color, consciousness level, and breathing rate, noting chest wall retractions, nasal flaring, and the use of accessory muscles. A complete airway obstruction often results in respiratory failure if not recognized and treated early.

Sudden onset of respiratory distress accompanied by coughing, stridor, wheezing, or gagging warrants emergent action and should illicit a high suspicion for FBAO. The choking individual may show the universal sign of airway obstruction by grabbing their neck with both hands. When the patient is stable, and a history can be obtained, particular attention should be given to age (typically very young or old), the presence of intellectual or neuromuscular disability, and precipitating events such as eating or playing with toys.

Classical physical examination features for laryngotracheal foreign bodies include stridor and hoarseness, while foreign bodies in the bronchi may present with unilateral wheezing and decreased breath sounds. A pharyngeal examination is essential. Visible foreign bodies should be removed cautiously, avoiding blind finger sweeps. The pharynx should also be examined for other causes of stridor and respiratory distress, such as epiglottitis and peritonsillar abscess.[18]

A history of sudden coughing and choking is highly predictive of FBAO. However, providers must maintain a high clinical suspicion in the absence of these manifestations in those who are dyspneic or hypoxic, as many may present without cough, stridor, or wheezes. Without these physical examination findings, providers should pay particular attention to risk factors such as age or disability and chest radiograph findings of atelectasis, lung hyperinflation, or pneumonia. While an abrupt onset of symptoms is common, the diagnosis cannot be excluded based on symptom duration alone, as many patients present more than 24 hours after foreign body aspiration.[19]

Evaluation

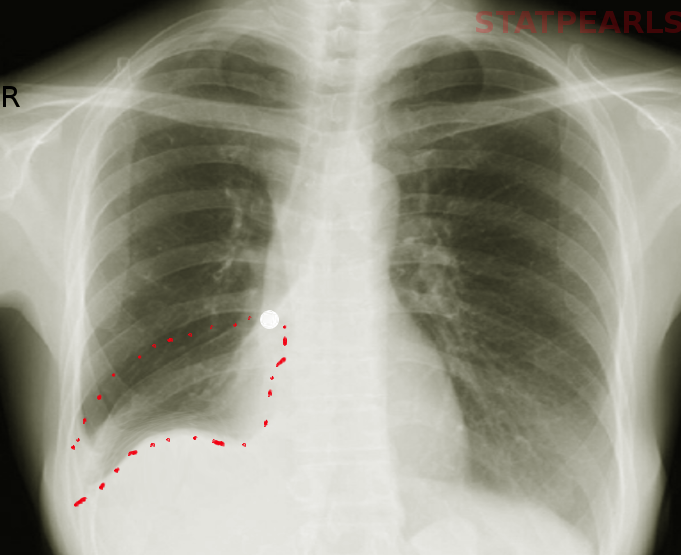

The diagnosis of FBAO is typically based on history and physical examination. Radiographs may help confirm the diagnosis but should not be solely relied upon to exclude FBAO. For example, chest radiographs often appear normal or may show abnormalities that are not typical of foreign body aspiration in children with airway foreign bodies.[19]

Upright lateral and frontal neck radiographs are recommended for suspected upper airway obstruction, while chest inspiratory and expiratory views may be added for lower airway obstruction. Most foreign bodies are radiolucent. Thus, indirect signs of obstruction, such as hypopharyngeal overdistension and prevertebral soft-tissue swelling, may aid in the diagnosis. Chest radiographs may reveal unilateral hyperinflation, atelectasis, or a mediastinal shift if the foreign body lodges in the lower airway regions. Expiratory views have been demonstrated to improve diagnostic accuracy. The affected lung often remains lucent in these images, with the air trapped distal to the foreign body.[20]

Treatment / Management

A child with a presumed airway obstruction who can still maintain some degree of ventilation should be allowed to clear the airway by coughing. If the child cannot cough, vocalize, or breathe, emergent steps are necessary to clear the airway. For infants younger than 1 year, alternating sequences of 5 back blows and 5 chest thrusts are performed until the object clears or the infant becomes unresponsive. Abdominal thrusts should not be performed in infants as their livers are injury-prone.

For a choking child older than 1 year, subdiaphragmatic abdominal thrusts (ie, the Heimlich maneuver) should be performed until the object is expelled or the child becomes unconscious. If the infant or child becomes unresponsive, chest compressions must be immediately started. The airway should be evaluated after 30 compressions. Visible foreign bodies require removal, but blind finger sweeps may push them downward to the larynx and should thus be avoided. A series of 30 compressions and 2 breaths should continue until the object is expelled.[21]

The treatment for complete FBAO in adults is similar to that of children, where a bystander performs the Heimlich maneuver until the foreign body is cleared or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if the patient loses consciousness. If nobody is present to assist in the Heimlich maneuver, the choking individual may self-administer thrusts with their fist or by forcibly leaning against a firm object such as the back of a chair. Abdominal thrusts may not be feasible in patients who are pregnant or morbidly obese, but sternal thrusts may be performed.[22]

If the above-described basic life support measures do not clear the obstruction, removal of the foreign body with Magill forceps or suction may be attempted under direct laryngoscopy. If the object is still causing obstruction and the clinician believes the foreign body is above the level of the vocal cords, a cricothyrotomy with trans-tracheal ventilation is appropriate. If the foreign body lodges below the level of the vocal cords, the clinician may attempt endotracheal intubation and use the endotracheal tube to advance the foreign body into the right mainstem bronchus. The endotracheal tube should then be withdrawn above the carina to allow ventilation of the left lung, with preparations for bronchoscopy in the operating room.

A diagnostic bronchoscopy should be strongly considered when a partial FBAO is suspected, even without radiological findings. All components of the diagnostic algorithm—clinical history, physical examination, and imaging—are evaluated together rather than in isolation before attempting a rigid bronchoscopy. The effectiveness of combining these diagnostic clues was assessed. The sensitivity was 95.2%, and the specificity was 15.1% if only 1 component is considered before diagnosing FBAO. Sensitivity and specificity are 84.6% and 58.2%, respectively, with 2 positive components. The combination of a positive history and physical exam has the highest overall accuracy, with a sensitivity of 58.7% and specificity of 90.2%. The sensitivity was 31.6%, and the specificity was 97.0% when all 3 components had positive results.[23]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for stridor, respiratory distress, and cough is vast and includes FBAO. Symptom onset and fever can help narrow the differential diagnosis. Sudden stridor, choking, or gagging without fever suggests FBAO, anaphylaxis, blunt or penetrating trauma, burn injury, or angioedema. A rapid onset of symptoms in a febrile child may indicate epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis, retropharyngeal abscess, or peritonsillar abscess.

A gradual-onset barking cough could be attributable to viral croup. Anatomical causes such as laryngotracheomalacia, vocal cord paralysis, subglottic stenosis, vascular rings, and airway hemangioma should be considered in children younger than 6 months. Esophageal foreign bodies are more common than airway foreign bodies and can contribute to respiratory compromise from mass effect and inflammation. Toddlers may also present with choking symptoms after ingesting caustic substances, such as cleaning supplies, bottled laundry detergent, or detergent “pods.”

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Research regarding FBAO is frequently reviewed by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, considering the condition's acute nature and need for emergent resuscitation. This committee, consisting of members from leading global resuscitation organizations, uses a Continuous Evidence Evaluation system, replacing the previous 5-year review cycle for resuscitative care recommendations.[24]

Prognosis

The prognosis of FBAO depends on the degree of obstruction and duration of hypoxia. Patients with partial FBAO who can clear the airway often experience few to no complications and may be treated based on their risk factors for future aspiration events. Meanwhile, loss of consciousness typically occurs within seconds or minutes in complete FBAO. Outcomes are bleak in patients requiring CPR, as mortality reaches 90% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Mortality reaches 60% to 70% for individuals who survive hospital admission.[25]

Neurological outcomes worsen as the duration of hypoxia increases. Still, the prognosis is often difficult to predict. Findings that portend a worse prognosis include absent pupillary light reflex, absent corneal reflex, myoclonus status epilepticus, and malignant electroencephalogram patterns such as burst suppression, generalized suppression, alpha coma, postanoxic status epilepticus, and nonreactive background. Guidelines recommend delaying the withdrawal of life-sustaining measures until at least 72 hours after the return of spontaneous circulation because of the difficulty in predicting outcomes.[26]

Complications

The most feared FBAO complication is hypoxia, resulting in respiratory arrest, anoxic brain injury, and death. Long-term complications of undiagnosed airway foreign bodies include atelectasis, pneumonia, and bronchiectasis, occasionally requiring lobectomy or segmentectomy. FBAO treatment may also cause side effects. Complications of the Heimlich maneuver include injury to the abdominal or thoracic viscera and regurgitation of stomach contents. Patients who undergo bronchoscopy may develop bleeding, infection, airway perforation, and pneumothorax.[27]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Several measures can reduce the risk of choking. In adults, food texture should be modified based on the sufficiency of the airway defense mechanism and cough strength. Problem foods should be avoided, mealtime posture improved, high-risk individuals adequately supervised, proper dental care ensured, and medication side effects monitored.[28]

For children, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends introducing pureed foods to infants between 4 and 6 months.[29] Certain behaviors, such as walking, talking, laughing, and eating quickly, may increase a child’s risk of choking. The AAP has proposed public health measures, such as mandatory food labeling for foods with high choking risks. The Child Safety Protection Act requires warning labels for choking hazards on certain toys and games.

FBAO is a typical emergency and a potential cause of sudden death in both children and older adults. The immediate bystander response significantly affects the condition’s outcome. Numerous essential life support training programs have recently been established for school children. These programs lack specific, detailed training in FBAO evaluation and management, which should be included in Basic Life Support training programs for school children.[30]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Complete FBAO is a medical emergency requiring immediate action by untrained bystanders to restore the victim's airway. The AAP recommends choking first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for parents, teachers, childcare providers, and other individuals who care for children. This training may also benefit nursing home staff and people caring for older adults. Pediatricians should continue to provide parents and caregivers guidance on appropriate food and toy selection as outlined by the AAP. The Child Safety Protection Act requires warning labels for choking hazards on certain toys in the United States, but no such system exists for high-risk foods. Emergency medical staff are well-versed in dealing with such situations and often train others. Food warning labels, a choking incident surveillance and reporting system, and choking prevention campaigns are some proposed legislative solutions to reduce choking incidents. Interprofessional coordination between emergency medical technicians, triage and emergency department nurses, providers, and surgeons improves outcomes.

Media

References

Saccomanno S, Saran S, Coceani Paskay L, De Luca M, Tricerri A, Mafucci Orlandini S, Greco F, Messina G. Risk factors and prevention of choking. European journal of translational myology. 2023 Oct 27:33(4):. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2023.11471. Epub 2023 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 37905785]

Oğuzkaya F, Akçali Y, Kahraman C, Bilgin M, Sahin A. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspirations in childhood: a 10-year experience. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1998 Oct:14(4):388-92 [PubMed PMID: 9845143]

Heimlich HJ. A life-saving maneuver to prevent food-choking. JAMA. 1975 Oct 27:234(4):398-401 [PubMed PMID: 1174371]

Cirilli AR. Emergency evaluation and management of the sore throat. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2013 May:31(2):501-15. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.01.002. Epub 2013 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 23601485]

Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010 Mar:125(3):601-7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2862. Epub 2010 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 20176668]

Mutolo D. Brainstem mechanisms underlying the cough reflex and its regulation. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2017 Sep:243():60-76. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2017.05.008. Epub 2017 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 28549898]

Tatar M, Hanacek J, Widdicombe J. The expiration reflex from the trachea and bronchi. The European respiratory journal. 2008 Feb:31(2):385-90 [PubMed PMID: 17959638]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWiddicombe J, Fontana G. Cough: what's in a name? The European respiratory journal. 2006 Jul:28(1):10-5 [PubMed PMID: 16816346]

Harris CS, Baker SP, Smith GA, Harris RM. Childhood asphyxiation by food. A national analysis and overview. JAMA. 1984 May 4:251(17):2231-5 [PubMed PMID: 6708272]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Toy-related injuries among children and teenagers--United States, 1996. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1997 Dec 19:46(50):1185-9 [PubMed PMID: 9414147]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerzlanovich AM, Fazeny-Dörner B, Waldhoer T, Fasching P, Keil W. Foreign body asphyxia: a preventable cause of death in the elderly. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005 Jan:28(1):65-9 [PubMed PMID: 15626557]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Nonfatal choking-related episodes among children--United States, 2001. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2002 Oct 25:51(42):945-8 [PubMed PMID: 12437033]

Hemsley B, Steel J, Sheppard JJ, Malandraki GA, Bryant L, Balandin S. Dying for a Meal: An Integrative Review of Characteristics of Choking Incidents and Recommendations to Prevent Fatal and Nonfatal Choking Across Populations. American journal of speech-language pathology. 2019 Aug 9:28(3):1283-1297. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0150. Epub 2019 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 31095917]

Norii T, Igarashi Y, Yoshino Y, Nakao S, Yang M, Albright D, Sklar DP, Crandall C. The effects of bystander interventions for foreign body airway obstruction on survival and neurological outcomes: Findings of the MOCHI registry. Resuscitation. 2024 Jun:199():110198. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2024.110198. Epub 2024 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 38582443]

Montoya D. Management of the choking victim. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 1986 Aug 15:135(4):305-11 [PubMed PMID: 3730995]

Escobar ML, Needleman J. Stridor. Pediatrics in review. 2015 Mar:36(3):135-7. doi: 10.1542/pir.36-3-135. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25733767]

Pfleger A, Eber E. Assessment and causes of stridor. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2016 Mar:18():64-72. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.10.003. Epub 2015 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 26707546]

Pfleger A, Eber E. Management of acute severe upper airway obstruction in children. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2013 Jun:14(2):70-7. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2013.02.010. Epub 2013 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 23598067]

Zerella JT, Dimler M, McGill LC, Pippus KJ. Foreign body aspiration in children: value of radiography and complications of bronchoscopy. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1998 Nov:33(11):1651-4 [PubMed PMID: 9856887]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDarras KE, Roston AT, Yewchuk LK. Imaging Acute Airway Obstruction in Infants and Children. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2015 Nov-Dec:35(7):2064-79. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150096. Epub 2015 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 26495798]

Berg MD, Schexnayder SM, Chameides L, Terry M, Donoghue A, Hickey RW, Berg RA, Sutton RM, Hazinski MF. Part 13: pediatric basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 2:122(18 Suppl 3):S862-75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971085. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20956229]

Ojeda Rodriguez JA, Ladd M, Brandis D. Abdominal Thrust Maneuver. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285362]

Lowe E, Soylu E, Deekonda P, Gajaweera H, Ioannidis D, Walker W, Amonoo-Kuofi K. Principal diagnostic features of paediatric foreign body aspiration. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2024 Feb:177():111846. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2023.111846. Epub 2023 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 38176114]

Berg KM, Bray JE, Ng KC, Liley HG, Greif R, Carlson JN, Morley PT, Drennan IR, Smyth M, Scholefield BR, Weiner GM, Cheng A, Djärv T, Abelairas-Gómez C, Acworth J, Andersen LW, Atkins DL, Berry DC, Bhanji F, Bierens J, Bittencourt Couto T, Borra V, Böttiger BW, Bradley RN, Breckwoldt J, Cassan P, Chang WT, Charlton NP, Chung SP, Considine J, Costa-Nobre DT, Couper K, Dainty KN, Dassanayake V, Davis PG, Dawson JA, de Almeida MF, De Caen AR, Deakin CD, Dicker B, Douma MJ, Eastwood K, El-Naggar W, Fabres JG, Fawke J, Fijacko N, Finn JC, Flores GE, Foglia EE, Folke F, Gilfoyle E, Goolsby CA, Granfeldt A, Guerguerian AM, Guinsburg R, Hatanaka T, Hirsch KG, Holmberg MJ, Hosono S, Hsieh MJ, Hsu CH, Ikeyama T, Isayama T, Johnson NJ, Kapadia VS, Kawakami MD, Kim HS, Kleinman ME, Kloeck DA, Kudenchuk P, Kule A, Kurosawa H, Lagina AT, Lauridsen KG, Lavonas EJ, Lee HC, Lin Y, Lockey AS, Macneil F, Maconochie IK, Madar RJ, Malta Hansen C, Masterson S, Matsuyama T, McKinlay CJD, Meyran D, Monnelly V, Nadkarni V, Nakwa FL, Nation KJ, Nehme Z, Nemeth M, Neumar RW, Nicholson T, Nikolaou N, Nishiyama C, Norii T, Nuthall GA, Ohshimo S, Olasveengen TM, Ong YG, Orkin AM, Parr MJ, Patocka C, Perkins GD, Perlman JM, Rabi Y, Raitt J, Ramachandran S, Ramaswamy VV, Raymond TT, Reis AG, Reynolds JC, Ristagno G, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Roehr CC, Rüdiger M, Sakamoto T, Sandroni C, Sawyer TL, Schexnayder SM, Schmölzer GM, Schnaubelt S, Semeraro F, Singletary EM, Skrifvars MB, Smith CM, Soar J, Stassen W, Sugiura T, Tijssen JA, Topjian AA, Trevisanuto D, Vaillancourt C, Wyckoff MH, Wyllie JP, Yang CW, Yeung J, Zelop CM, Zideman DA, Nolan JP, Collaborators. 2023 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces. Circulation. 2023 Dec 12:148(24):e187-e280. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001179. Epub 2023 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 37942682]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFugate JE. Anoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Neurologic clinics. 2017 Nov:35(4):601-611. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2017.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28962803]

Elmer J, Callaway CW. The Brain after Cardiac Arrest. Seminars in neurology. 2017 Feb:37(1):19-24. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597833. Epub 2017 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 28147414]

Divarci E, Toker B, Dokumcu Z, Musayev A, Ozcan C, Erdener A. The multivariate analysis of indications of rigid bronchoscopy in suspected foreign body aspiration. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2017 Sep:100():232-237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.012. Epub 2017 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 28802379]

Samuels R, Chadwick DD. Predictors of asphyxiation risk in adults with intellectual disabilities and dysphagia. Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR. 2006 May:50(Pt 5):362-70 [PubMed PMID: 16629929]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKleinman RE. American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for complementary feeding. Pediatrics. 2000 Nov:106(5):1274 [PubMed PMID: 11061819]

Martínez-Isasi S, Carballo-Fazanes A, Jorge-Soto C, Otero-Agra M, Fernández-Méndez F, Barcala-Furelos R, Izquierdo V, García-Martínez M, Rodríguez-Núñez A. School children brief training to save foreign body airway obstruction. European journal of pediatrics. 2023 Dec:182(12):5483-5491. doi: 10.1007/s00431-023-05202-x. Epub 2023 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 37777603]