Introduction

Trauma is an important cause of cornea blindness and is second only to corneal ulcers causing severe vision loss. It is an important cause of unilateral vision loss in developing countries. Scleral and limbic laceration can result from sharp pointed objects, scissors, thorns, iron nails, fish hooks, wood pieces, etc.[1] The open globe injuries result in irreversible visual sequelae and cause substantial financial loss and psychological impact on the patient and their families.[2]

The patients usually present with a history of pain, redness, and sudden loss of vision of short duration. The mode, duration, time of onset, and object type should be documented. A detailed, meticulous slit lamp evaluation is mandated to rule out sclerolimbal tear, occult globe rupture, posterior scleral tear, impacted intraocular foreign body, corneal infiltrate, endophthalmitis and panophthalmitis.[3]

Seidel’s test should be performed to rule out the aqueous leak, and imaging in the form of a B scan is done to rule out retinal detachment, choroidal detachment, nucleus drop, cortex drop, or posterior subluxation of IOL. X-ray, CT scan, and MRI may be required to rule out the impacted foreign body.[4]

Smear and culture are mandated in cases of infected lacerations. Imaging should be performed postoperatively when the anatomical configuration of the globe is retained. Each case should be documented with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and pinhole acuity.[5] The treatment is suturing the laceration with 9-0 and 10-0 nylon sutures. The surgery usually requires a long time, and the prognosis is grave in most cases. This activity focuses on etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, evaluation, treatment, complication, and prognosis of scleral and limbic lacerations.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A scleral and limbic laceration usually results from sharp and pointed objects injuring the globe with high velocity. These injuries are most common in the workplace, industry, factory, and home in the case of children.[7] Open globe injuries are usually a by-product of domestic violence, chemical trauma, industrial fire, and workplace accidental injuries. Blunt trauma can also predispose to scleral and limbic lacerations.[8]

A previous study from the US reported rock, fist of hand, baseball trauma, and weight-related injuries to be most common. The lacerations are commonly noticed in children with pencils, knives, scissors, stones, iron nails, screwdrivers, cranes, swans, cat paws, and wire injuries.[9]

The most common mode in elderly and older people is self-fall, slippage in the bathroom, and falls from two-wheelers. Intraocular foreign bodies like the iron piece, wood piece, thorn, iron nail, and stone can also get impacted and account for approximately 40% of open globe injuries.[10]

Epidemiology

Scleral and limbic lacerations are more common in males than females, affecting males five times more than females.[11]

Open globe injury is also more common in the younger age group, with approximately 50% of patients below 40 years of age. May et al., in their analysis, reported that 58% of the patients were less than 30 years of age. In the third decade, the male to female ratio was 4.6 to 1, reaching 7.4 to 1 in the fourth decade. Approximately 50% have associated retinal trauma and 77% required surgical intervention.

Kuhn et al. analyzed the United states eye injury registry (USEIR) data and Hungarian eye injury registry (HEIR) data and found that 6% of US and 52% of Hungary patients were less than 30 years and approximately 80% were males. Home injuries were the most common in both countries and gun injuries were most common in the US, and champagne cork injuries were common in Hungary.[12]

Pathophysiology

Scleral lacerations usually result from internal ocular pressure caused by blunt trauma. The scleral injuries result in weak spots in the sclera and the limbus.[13] These injuries typically manifest behind the ocular muscles and adjacent to the optic nerve. The injuries are usually circumferential and may be radial. The injuries may extend radially if the damage is severe.[14]

Scleral tears also occur by an inside-out mechanism through superior or temporal scleral tunnel and result in prolapse of uveal tissue. Scleral tears adjacent to the limbus are sometimes difficult to distinguish, and very posterior tears are also challenging to determine. Occult scleral tears are usually located near the equator, and the conjunctiva is intact. Detailed knowledge of the mechanism will help to better locate the injury.[15]

Direct Blow

In scleral tear with a direct blow with the sharp-pointed object, the rupture at the site of impact.[16]

Diffuse Injury

In the case of diffuse traumatic force, there will be indirect trauma to the scleral tunic as the force is transmitted according to hydraulic law principles.[17]

In some cases, the indirect force may result In scleral rupture near the limbus, a weak area studded with Schlemm canal and perforating vessels. In the case of staphyloma, the scleral rupture is seen adjacent to it or at the staphyloma site. The sclera is the thinnest between the insertion of extraocular muscles and the equator; hence the injury is most common here. Posterior scleral rupture is often missed and has been documented less frequently. Limbal laceration can result from penetrating or direct, blunt trauma and is usually associated with iris prolapse.[18]

History and Physical

A thorough and meticulous history should be documented in every suspected scleral and limbic laceration. A detailed account of traumatic events is essential, like mode, onset, time, and injury site. Any history of treatment in casualty or any first aid given is important. The history of protective measures used like safety glasses or face shields at the workplace is important. Any associated injuries should be assessed like head injuries, bony injuries, etc.[19]

History of previous cataract surgery should be enquired. Life-threatening injuries should be managed first. A history of systemic ailments must be obtained, and history of tetanus injection, drug allergy, and time of last meal should be documented. Any history of previous ocular injury must be documented. History of amblyopia, patching of the eye, and muscle surgery must be documented.[20] The clinician must rule out a history of symptoms like headache, brow pain, eye pain, nausea, and vomiting. Some patients may complain of pain, double vision, vision loss, blurred vision, redness, photophobia, and foreign body sensation.[21]

A detailed history helps us to focus on a meticulous slit-lamp examination.[22] Multiple slit lamp illumination techniques should be utilized to pinpoint minor injuries. The most common form of slit lamp illumination is direct, and care should be taken to avoid excess photophobia in the patient. A neutral density filter can reduce illumination in the uncooperative patient.[22]

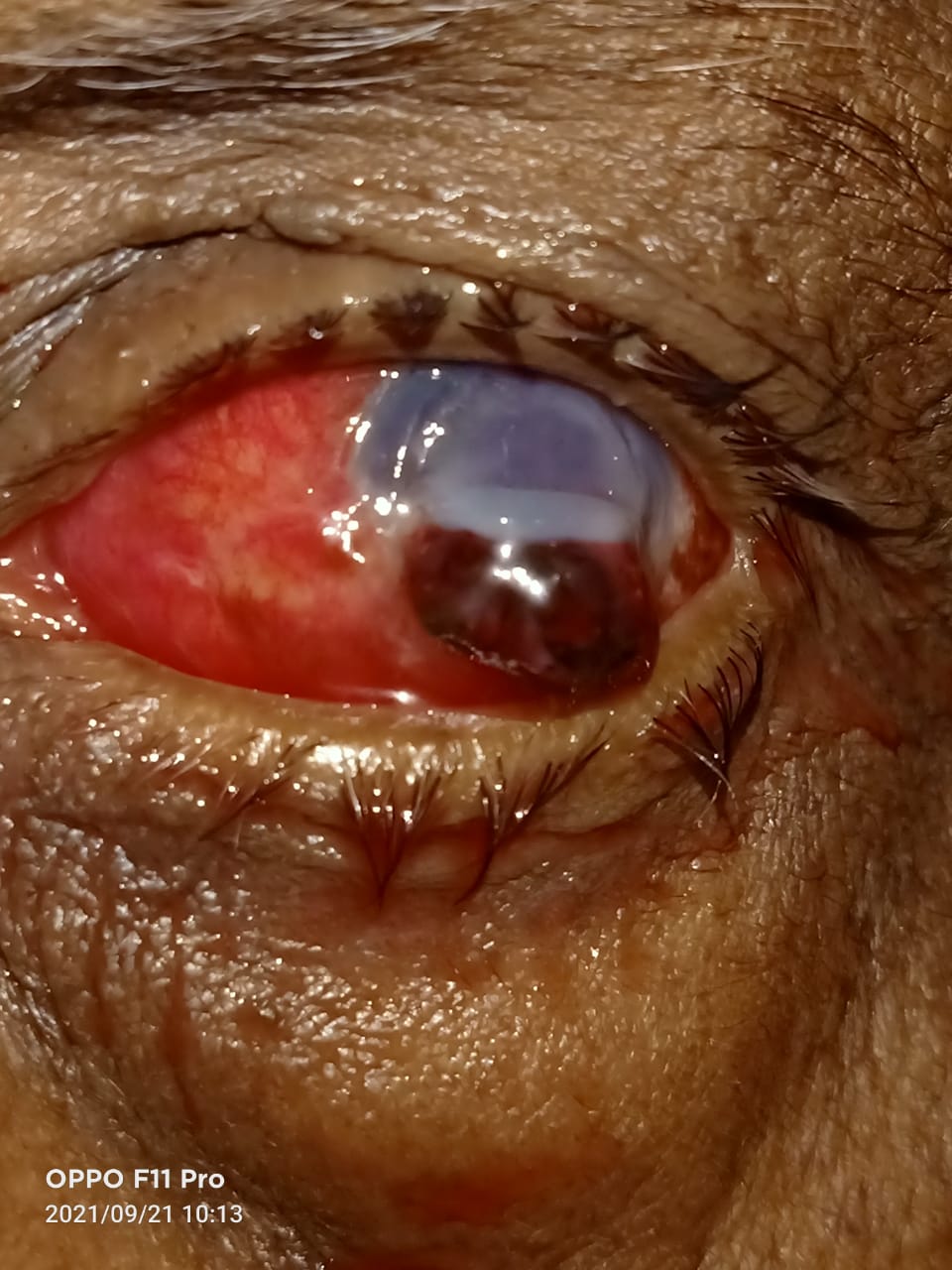

Detailed slit lamp evaluation in scleral laceration may reveal subconjunctival hemorrhage, conjunctival congestion, and scleral laceration. There may or may not be associated corneal tear, shallow or flat anterior chamber hyphema, iris prolapse, peaked pupil, traumatic cataract, or subluxated or dislocated lens. The fundus finding may reveal choroidal detachment, retinal detachment, retinal tears, vitreous hemorrhage, and there may be impacted intraocular foreign body.[23]

All the above findings may be seen in a limbic laceration and a limbal tear. Careful orbital and adnexal inspection is essential to rule out orbital rim fractures, lid tears, canalicular injury, abrasion, contusions, and ecchymosis. There may also be associated vitreous prolapse at the site of the laceration. Is it equally important to examine the fellow eye to rule out any associated trauma or complication like sympathetic ophthalmia.[24]

A general physical examination is vital to rule out any systemic issues. If the patient is unconscious or if there is pain, nausea, headache, vomiting, and deranged Glasgow coma scale, then the systemic condition has to be managed first.[25]

Evaluation

Visual Acuity

Snellen’s uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuity and pinhole acuity should be documented in each case. Visual acuity on serial follow-ups helps to ascertain improvement in the ocular condition. Moreover, it is necessary to document visual acuity to avoid medicolegal issues. Perception of light and perception of rays must be documented in cases of severe trauma where visual acuity is doubtful.[26]

Intraocular Pressure

Non-contact tonometry can be obtained in small scleral tears, but in cases of large scleral lacerations and limbic laceration, the tonometry should be avoided to avoid pressure on the globe.[27]

Seidel’s Test

This assesses aqueous leaks in case of total thickness laceration. Aqueous is a transparent fluid, and when it leaks, it gets mixed with the transparent tear film preventing identification. Hence in this non-invasive procedure, when fluorescein dye is applied at the tear site, identifying an aqueous leak becomes easy. The dye becomes diluted with the aqueous leak, and thus identification of the leak becomes easy.

Forced Seidel’s Test

In this test, the same procedure is followed as in seidel’s test, except that globe is compressed from the lid or at the tear to determine an occult leak in case of self-sealed lacerations.[28]

Microbiological Smear and Culture

In case of infected lacerations, smear and culture can be taken preoperatively or intraoperatively from the margins of the wounds, devitalized excised tissue, and associated IOFB, if any. This will help to ascertain the microorganism and targeted treatment of the patients.[29]

Imaging

X-Ray

X-ray anteroposterior (AP) view and lateral view are essential to rule out or locate any impacted intraocular foreign body (IOFB).[30]

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scan should be done to assess any bony injury and lodgement of impacted intraocular foreign body (IOFB). CT scan in 1 mm thin slices in the axial, sagittal, and coronal plane will help locate IOFB, which is expected in 40% of the cases.[31]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is essential to assess the soft tissue injury and impacted foreign body. It is to be noted that MRI is contraindicated in cases of ferromagnetic foreign body.[32]

B Scan Ultrasonography

B scan should be avoided preoperatively to prevent compression over the globe. B scan is helpful postoperatively if the media is hazy or the pupil is small to rule out retinal detachment, choroidal detachment, optic nerve cupping, retinochoroidal thickening, posterior scleritis, nucleus drop, and IOL drop. B scan ultrasound has been found to have a 100% positive predictive value for detecting retinal detachment and IOFB.[33]

Optical Coherence Tomography

This investigation is helpful to rule out the epiretinal membrane and macular edema.[34]

Visual Fields

A confrontation test must be done in doubtful cases.[35]

Gonioscopy forced duction test and scleral depression during indirect ophthalmoscopy should be avoided because these investigations will cause depression of the globe and extrusion of intraocular contents.[36]

Treatment / Management

Preoperative Management

Preservative-free topical drops are preferred to prevent intraocular migration of drops. In laceration with uveal tissue and vitreous prolapse, the patient should be started on broad-spectrum topical antibiotics like 0.5% moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin. The patient should be given a single shot of injection tetanus 0.5 ml IM stat and injection IV ceftriaxone 1 gram two times per day for three days in adults and 500 mg two times for three days in the case of pediatric children. Some surgeons prefer intravenous cefazolin or vancomycin for gram-positive coverage and third-generation cephalosporin for gram-negative coverage. Clindamycin is preferred for vegetative intraocular foreign bodies. For general anesthesia, the patient should be kept nil per oral for 8 hours.[37]

Wound Repair Principle

Primary Aim

To achieve anatomical integrity with wound closure without any leak.[38]

Secondary Aim

To achieve an excellent anatomical and possibly functional outcome with abscission of prolapsed uveal tissue, vitreous, foreign body, and removal of dead and devitalized tissue.

Keratorefractive Principle

Limbic laceration due to the micromechanical effect of penetrating injuries is highly important in facilitating anatomical restoring and achieving a perfect visual outcome.[34]

Eisner Principle

Limbic laceration produces flattening due to the gaping of the wound. This principle states that if the incision is given through the wall of the globe, it produces valves whose margins of water tightness are equal to the surface tension projection on the surface of the globe. Thus to conclude, beveled incisions show less gaping than vertical incisions. The beveled incisions may self-seal, but the vertical incisions will require opposition with sutures.[39]

The Suture Effect

The sutures cause a flattening effect when applied and result in steeping of the cornea in the center and near the visual axis.[40] The various components of the suture effect are

- Compression factor

- Torque

- Splinting

- Tissue eversion

- Tissue inversion

Principles of Scleral and Limbic Laceration Repair

The primary goal is the restoration of anatomical landmarks. The first step is conjunctival peritomy to open up the scleral laceration a few hours away from the primary wound. They help assess the extent of scleral laceration except for very posterior tears. The sclera should be sutured clock hourwise to prevent prolapse of intraocular contents. This technique is helpful as it involves less anterior dissection, exposure of minor scleral defect, and helps in the closure of the anterior defect. The laceration that is too posterior can be left to heal without any risk of loss of intraocular contents. Since the sclera heals slowly, 9-0 nylon or 8-0 mersilene nonabsorbable sutures can be used to close the significant defects. For small defect absorbable 8-0 vicryl sutures can be used. In muscle injury associated with a scleral tear, the muscle can be disinserted, and sclera laceration can be repaired first. Later the muscle should be opposed. In case of a combination of a sclerocorneal laceration, the first stay suture should be at the limbus to restore anatomy. Then the corneal wound and lastly, the scleral laceration should be sutured.[41]

Difficulties in Scleral and Limbic Laceration Repair

Patch Grafting

In case of large scleral lacerations with tissue loss that can’t be opposed with direct closure will require a patch graft. Frozen sclera can be used for three months, and glycerine preserved sclera can be used for a year.[42]

Adjunctive Procedures

Uveal Tissue Abscission

If there is prolapse of uveal tissue and the injury occurred less than 4 hours ago, the iris can be reposited if there are no infective foci or necrosis. If the tissue prolapse has occurred for more than 4 hours and there is associated necrotic and infective tissue, the uveal tissue should be abscised.[43](B3)

Lens Removal

If the anterior lens capsule is damaged, there is cortical matter disturbance, or if there is a vision-threatening cataract, it mandates lens removal, and primary IOL implantation should be deferred.[44]

Surface Vitrectomy

If there is vitreous prolapse over the corneal or scleral surface, it should be cut with a Vannas scissor.[45]

Automated Anterior Vitrectomy

If there is vitreous prolapse in the anterior chamber, it should be removed with the help of an automated anterior vitrectomy.[46]

Cryotherapy

This can be done with scleral tear repair if there is a retinal break in the superior eight-clock hours.[47]

Differential Diagnosis

Prognosis

The prognosis of sclerolimbic lacerations depends on the extent of injury, time of injury, mode of trauma, damage to the surrounding structures, presence of RAPD, presenting visual acuity, wound location, length of tear, mechanism of trauma, presence of retinal detachment, choroidal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage and dislocation or subluxation of lens. The prognosis is usually good if the presenting visual acuity is better than 6/60, the wound is located anterior to pars plana, the tear length is less than 10 mm, and there is a sharp mechanism of injury. The ocular trauma score is also a good predictor of visual outcome.[7]

Complications

- Wound leak

- Conjunctival retraction

- Suture infiltrate

- Epithelial downgrowth

- Fibrous ingrowth

- Corneal infiltrates

- Secondary glaucoma

- Angle recession glaucoma

- Iris prolapse

- Aniridia

- Cataract

- Traumatic uveitis

- Vitreous prolapse

- Retinal detachment

- Choroidal detachment

- Choroidal rupture

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Sympathetic ophthalmia

- Endophthalmitis

- Panophthalmitis

- Phthisis bulbi

- Atrophic bulbi

- Permanent blindness

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

All patients with non-infective scleral and limbic lacerations should be managed with topical steroids (0.1% dexamethasone or 1% prednisolone) 6/5/4/3/2/1 one week each along with topical antibiotics 0.5% moxifloxacin or 0.5% gatifloxacin four times for 15 days and topical lubricating eye drops in the form of 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose four times per day for 30 days. To rule out any retinal pathology, all scleral laceration patients must undergo a dilated fundus evaluation.[50]

If the media is hazy, the patient should undergo a B scan to locate any fundus pathology. The patient should be followed up for one week, then two weekly each. If there is a non-resolving vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment, the patient will require vitreoretinal surgery. In patients with ciliary shutdown or cyclodialysis, the result may be Phthisis bulbi. Steroids are contraindicated in cases with infective scleral or limbic laceration; topical antibiotics (0.5% moxifloxacin or 0.5% gatifloxacin ) and antifungals (5% natamycin or 1% itraconazole or 1% voriconazole) should be used. These cases should be closely followed to prevent the development of endophthalmitis or panophthalmitis.[51]

Consultations

Any patient having a history of blunt or penetrating trauma should be evaluated in detail by ophthalmologists to rule out scleral or limbic laceration. The patient should be evaluated systematically as well looked for any associated injury. The patient should be referred to a cornea and external disease specialist for expert surgical management of these cases. The patients landing with retinal complications should be managed with expert advice from the vitreoretinal surgeon for the need for pars plana vitrectomy, cryotherapy, or scleral buckle surgery. The patients developing secondary glaucoma should be managed with the help of a glaucoma expert. In the case of uveitic sequelae, a uvea expert should be consulted. Patients with traumatic cataracts should be managed by a cornea and cataract surgeon.[52]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient with scleral and limbic laceration should be explained the need for surgery and prognosis based on various risk factors. The patients should be explained the need for timely use of medications and regular follow-up. The patient should be explained the nature of the pathology and should be told to have realistic expectations.[53]

Pearls and Other Issues

The patients with open globe injury having scleral and limbic laceration should be evaluated meticulously, and timely surgical intervention is mandated in these cases. The prognosis depends on various factors, as listed above. Prompt diagnosis, meticulous management, and regular follow-up result in a good outcome in each case.[54]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

To enhance healthcare team outcomes, it is the responsibility of the operating cornea and external disease specialist to manage it surgically with a good outcome. The nursing team assists in the operating room during surgery, helps in preoperative and postoperative care, and helps in counseling and regular follow-up of the patients—the pharmacist help in arranging the necessary medication. The counselor helps in preoperative and postoperative counseling and helps in explaining the prognosis of the case. The cornea surgeon helps manage the scleral and limbic lacerations, the vitreoretinal surgeon help in managing the retinal complications, and the glaucoma surgeon help in managing secondary glaucoma. The final anatomical and functional outcome is a result of the multidisciplinary role of the team.[55]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Burton MJ. Prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. Community eye health. 2009 Dec:22(71):33-5 [PubMed PMID: 20212922]

Chen H, Han J, Zhang X, Jin X. Clinical Analysis of Adult Severe Open-Globe Injuries in Central China. Frontiers in medicine. 2021:8():755158. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.755158. Epub 2021 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 34778317]

Couperus K, Zabel A, Oguntoye MO. Open Globe: Corneal Laceration Injury with Negative Seidel Sign. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine. 2018 Aug:2(3):266-267. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2018.4.38086. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 30083651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCampbell TD, Gnugnoli DM. Seidel Test. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082063]

Thevi T, Mimiwati Z, Reddy SC. Visual outcome in open globe injuries. Nepalese journal of ophthalmology : a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal of the Nepal Ophthalmic Society : NEPJOPH. 2012 Jul-Dec:4(2):263-70. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v4i2.6542. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22864032]

McClellan KA, Knol A, Billson FA. Nonabsorbable suture material in corneoscleral sections--a comparison of novafil and nylon. Ophthalmic surgery. 1989 Jul:20(7):480-5 [PubMed PMID: 2779951]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYucel OE, Demir S, Niyaz L, Sayin O, Gul A, Ariturk N. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of scleral rupture due to blunt ocular trauma. Eye (London, England). 2016 Dec:30(12):1606-1613. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.194. Epub 2016 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 27589050]

Ibramsah AB,Masnon NA,Ibrahim M,Wan Hitam WH, Open Globe Injury Secondary to [PubMed PMID: 34984136]

Kaplan N, Kim M, Slavin B, Kaplan L, Thaller SR. Baseball-Related Craniofacial Injury Among the Youth: A National Electronic Injury Surveillance System Database Study. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2022 Jun 1:33(4):1063-1065. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000008404. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34879017]

Liu CC, Tong JM, Li PS, Li KK. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of intraocular foreign bodies in Hong Kong: a 13-year review. International ophthalmology. 2017 Feb:37(1):55-61. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0225-4. Epub 2016 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 27043444]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMay DR, Kuhn FP, Morris RE, Witherspoon CD, Danis RP, Matthews GP, Mann L. The epidemiology of serious eye injuries from the United States Eye Injury Registry. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2000 Feb:238(2):153-7 [PubMed PMID: 10766285]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKuhn F, Mester V, Berta A, Morris R. [Epidemiology of severe eye injuries. United States Eye Injury Registry (USEIR) and Hungarian Eye Injury Registry (HEIR)]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 1998 May:95(5):332-43 [PubMed PMID: 9643026]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen X, Yao Y, Wang F, Liu T, Zhao X. A retrospective study of eyeball rupture in patients with or without orbital fracture. Medicine. 2017 Jun:96(24):e7109. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007109. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28614230]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRoth FS, Koshy JC, Goldberg JS, Soparkar CN. Pearls of orbital trauma management. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2010 Nov:24(4):398-410. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269769. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22550464]

Pirouzian A, O'Halloran H, Scher C, Jockin Y, Yaghmai R. Traumatic and spontaneous scleral rupture and uveal prolapse in osteogenesis imperfecta. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2007 Sep-Oct:44(5):315-7. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20070901-11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 17913179]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoyette JR, Pemberton JD, Bonilla-Velez J. Management of orbital fractures: challenges and solutions. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2015:9():2127-37. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S80463. Epub 2015 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 26604678]

Zmuda Trzebiatowski MA, Kłosowski P, Skorek A, Żerdzicki K, Lemski P, Koberda M. Validation of Hydraulic Mechanism during Blowout Trauma of Human Orbit Depending on the Method of Load Application. Applied bionics and biomechanics. 2021:2021():8879847. doi: 10.1155/2021/8879847. Epub 2021 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 33747122]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCosta EF, Pinto LM, Campos MAG, Gomes TM, Silva GEB. Partial regression of large anterior scleral staphyloma secondary to rhinosporidiosis after corneoscleral graft - a case report. BMC ophthalmology. 2018 Feb 27:18(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0725-2. Epub 2018 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 29486755]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMwangi N, Mutie DM. Emergency management: penetrating eye injuries and intraocular foreign bodies. Community eye health. 2018:31(103):70-71 [PubMed PMID: 30487690]

Leffler CT, Klebanov A, Samara WA, Grzybowski A. The history of cataract surgery: from couching to phacoemulsification. Annals of translational medicine. 2020 Nov:8(22):1551. doi: 10.21037/atm-2019-rcs-04. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33313296]

Schwartz DP, Robbins MS. Primary headache disorders and neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations. Eye and brain. 2012:4():49-61. doi: 10.2147/EB.S21841. Epub 2012 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 28539781]

Martin R. Cornea and anterior eye assessment with slit lamp biomicroscopy, specular microscopy, confocal microscopy, and ultrasound biomicroscopy. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Feb:66(2):195-201. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_649_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29380757]

Gilani CJ, Yang A, Yonkers M, Boysen-Osborn M. Differentiating Urgent and Emergent Causes of Acute Red Eye for the Emergency Physician. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Apr:18(3):509-517. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.12.31798. Epub 2017 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 28435504]

Lin KY, Ngai P, Echegoyen JC, Tao JP. Imaging in orbital trauma. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2012 Oct:26(4):427-32. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.08.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23961028]

Cooksley T, Rose S, Holland M. A systematic approach to the unconscious patient. Clinical medicine (London, England). 2018 Feb:18(1):88-92. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-1-88. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29436445]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim JJ, Moon JH, Jeong HS, Chi M. Has decreased visual acuity associated with blunt trauma at the emergency department recovered? The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2012 May:23(3):630-3. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824db77a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22565865]

Maheshwari R, S Choudhari N, Deep Singh M. Tonometry and Care of Tonometers. Journal of current glaucoma practice. 2012 Sep-Dec:6(3):124-30. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10008-1119. Epub 2012 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 26997768]

Baswati P, Samiksha C, Subodh S, Abhishek D. Revision of dysfunctional filtering bleb by conjunctival advancement with bleb preservation: A simple choice for massive choroidals with hypotony following trabeculectomy. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2013 Oct:27(4):287-90. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.07.001. Epub 2013 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 24371426]

Bhala S, Narang S, Sood S, Mithal C, Arya SK, Gupta V. Microbial contamination in open globe injury. Nepalese journal of ophthalmology : a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal of the Nepal Ophthalmic Society : NEPJOPH. 2012 Jan-Jun:4(1):84-9. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v4i1.5857. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22344003]

Jung HC, Lee SY, Yoon CK, Park UC, Heo JW, Lee EK. Intraocular Foreign Body: Diagnostic Protocols and Treatment Strategies in Ocular Trauma Patients. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Apr 25:10(9):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091861. Epub 2021 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 33923011]

Pokhraj P S, Jigar J P, Mehta C, Narottam A P. Intraocular metallic foreign body: role of computed tomography. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2014 Dec:8(12):RD01-3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9949.5271. Epub 2014 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 25654008]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRao SK, Nunez D, Gahbauer H. MRI evaluation of an open globe injury. Emergency radiology. 2003 Dec:10(3):144-6 [PubMed PMID: 15290503]

Edo A,Harada Y,Kiuchi Y, Usefulness of B-scan ocular ultrasound images for diagnosis of optic perineuritis. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2018 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 30182069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMayer CS, Reznicek L, Baur ID, Khoramnia R. Open Globe Injuries: Classifications and Prognostic Factors for Functional Outcome. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Oct 8:11(10):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11101851. Epub 2021 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 34679549]

Pandit RJ, Gales K, Griffiths PG. Effectiveness of testing visual fields by confrontation. Lancet (London, England). 2001 Oct 20:358(9290):1339-40 [PubMed PMID: 11684217]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrevino R, Stewart B. Change in intraocular pressure during scleral depression. Journal of optometry. 2015 Oct-Dec:8(4):244-51. doi: 10.1016/j.optom.2014.09.002. Epub 2014 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 25444648]

Sugioka K, Fukuda M, Komoto S, Itahashi M, Yamada M, Shimomura Y. Intraocular penetration of sequentially instilled topical moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, and levofloxacin. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2009:3():553-7 [PubMed PMID: 19898627]

Bowler PG, Duerden BI, Armstrong DG. Wound microbiology and associated approaches to wound management. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2001 Apr:14(2):244-69 [PubMed PMID: 11292638]

Mutie D, Mwangi N. Managing eye injuries. Community eye health. 2015:28(91):48-9 [PubMed PMID: 26989311]

van Rij G, Waring GO 3rd. Changes in corneal curvature induced by sutures and incisions. American journal of ophthalmology. 1984 Dec 15:98(6):773-83 [PubMed PMID: 6391181]

Rathi A, Sinha R, Aron N, Sharma N. Ocular surface injuries & management. Community eye health. 2017:30(99):S11-S14 [PubMed PMID: 29849439]

Kompa S, Redbrake C, Arend O, Remky A. [Defect closure with scleral grafts]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2004 Oct:221(10):867-71 [PubMed PMID: 15499523]

Marr BP, Shields JA, Shields CL, Materin MA, Tuncer S. Uveal prolapse following cataract extraction simulating melanoma. Ophthalmic surgery, lasers & imaging : the official journal of the International Society for Imaging in the Eye. 2008 May-Jun:39(3):250-1 [PubMed PMID: 18556954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen D, Vasavada A. Cataract and surgery for cataract. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2006 Jul 15:333(7559):128-32 [PubMed PMID: 16840470]

Shimada H, Nakashizuka H, Hattori T, Mori R, Mizutani Y, Yuzawa M. Vitreous prolapse through the scleral wound in 25-gauge transconjunctival vitrectomy. European journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Jul-Aug:18(4):659-62 [PubMed PMID: 18609496]

Astbury N, Wood M, Gajiwala U, Patel R, In the Sewa Rural Team, Chen Y, Benjamin L, Abuh SO. Management of capsular rupture and vitreous loss in cataract surgery. Community eye health. 2008 Mar:21(65):6-8 [PubMed PMID: 18504467]

Kang HK, Luff AJ. Management of retinal detachment: a guide for non-ophthalmologists. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2008 May 31:336(7655):1235-40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39581.525532.47. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18511798]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Traumatic Iris Reconstruction. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35201728]

Gurnani B, Kaur K, Sekaran S. First case of coloboma, lens neovascularization, traumatic cataract, and retinal detachment in a young Asian female. Clinical case reports. 2021 Sep:9(9):e04743. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4743. Epub 2021 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 34484773]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFung AT, Tran T, Lim LL, Samarawickrama C, Arnold J, Gillies M, Catt C, Mitchell L, Symons A, Buttery R, Cottee L, Tumuluri K, Beaumont P. Local delivery of corticosteroids in clinical ophthalmology: A review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2020 Apr:48(3):366-401. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13702. Epub 2020 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 31860766]

Sudharshan S, Ganesh SK, Biswas J. Current approach in the diagnosis and management of posterior uveitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Jan-Feb:58(1):29-43. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.58470. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20029144]

. Assessing and managing eye injuries. Community eye health. 2005 Oct:18(55):101-4 [PubMed PMID: 17491766]

Torrance AD, Powell SL, Griffiths EA. Emergency surgery in the elderly: challenges and solutions. Open access emergency medicine : OAEM. 2015:7():55-68. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S68324. Epub 2015 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 27147891]

Andreoli MT, Andreoli CM. Surgical rehabilitation of the open globe injury patient. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012 May:153(5):856-60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.013. Epub 2012 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 22265150]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlomberg AC, Bisholt B, Lindwall L. Responsibility for patient care in perioperative practice. Nursing open. 2018 Jul:5(3):414-421. doi: 10.1002/nop2.153. Epub 2018 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 30062035]