Introduction

Many dermatological conditions are associated or present with nail abnormalities. Clinical examination of the nails may be insufficient to provide a straightforward diagnosis; often, additional evaluation is required. Although biopsy-based histopathological evaluation remains the gold standard for many cutaneous diagnoses, nail unit biopsies can be challenging for clinicians and uncomfortable for patients. As a routine evaluation, dermoscopy of the nails, or onychoscopy, has aided the diagnosis of many lesions and limited the need for further procedural intervention.[1] However, when further investigations such as nail unit biopsy become necessary, onychoscopy can also aid intraoperative biopsy site selection.[2]

Onychoscopy is used to evaluate the nail matrix and nail bed, structures customarily obscured by the nail plate. The initial use of onychoscopy was primarily for evaluating nail-pigmented lesions such as melanonychia, yet the scope has expanded to include nonpigmented lesions and tumors.[3][4][5] Recent literature has emphasized its use in inflammatory and infectious disorders with nail involvement, such as lichen striatus, psoriasis, connective tissue disorders, and onychomycosis.[3][6] As onychoscopy highlights changes in the nail unit that the naked eye would otherwise miss, it can optimize investigations in dermatologic diagnosis. Thus, onychoscopy is a diagnostic bridge between clinical morphology and histopathological evaluation of nail disorders.

Onychoscopy may be performed as nonpolarized dermoscopy, polarized noncontact (dry) dermoscopy, or polarized contact (wet) dermoscopy (see Image. Nail Plate, Wet Dermoscopy).[7][8] Nonpolarized dermoscopy is used first to detect surface abnormalities, like longitudinal ridges, trachyonychia (rough and ridged nails), or surface pits. Polarized noncontact dermoscopy is used for deeper structures beneath the nail plate, allowing for a better appreciation of colors, hues, specific signs, and vessels. Polarized contact dermoscopy typically employs a linkage fluid between the dermoscopic lens and nail structure and is sometimes used for clarity and detail enhancement (see Image. Onychoscopy, Dermatologic Diagnosis).[9] Onychoscopy provides good detail but should be used with other clinicopathologic information. Some challenges to its use have included equipment cost, training, and lack of information. The International Dermoscopy Society and the Council for Nail Disorders, among other organizations, have committed to disseminating information on nail disease and evaluation. For further training and information, please visit their respective websites.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The nail unit is a complex structure composed of the nail plate, nail matrix, nail bed, cuticle, and surrounding tissues. Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the nail unit is essential for recognizing normal function and identifying pathological changes.

Gross Anatomy of the Nail Unit

The nail unit of a human digit includes the nail plate (surface and free edge), nail bed, nail matrix (proximal and distal/germinal), proximal nail fold, lateral nail folds, cuticle (distal crease of eponychium), paronychium, and hyponychium.[10] The nail bed, nail folds, eponychium, paronychium, and hyponychium are also called the perionychium. The tissues beneath the nail are divided into the matrix (15% to 25%) and the nail bed (75% to 85%).[11]

The nail matrix has a proximal (keratogenous) and distal (germinal) component. The distal portion often has a visible part called the lunula—a pale white, crescent-shaped portion most apparent on the thumb with relatively less exposure in other digits. The light creates the whitish hue of the lunula reflected off the nuclei in the keratogenous zone. The proximal portion of the nail matrix composes most of the nail plate overall, specifically the superficial/dorsal portion of the nail plate, while the distal portion contributes to the ventral nail plate.[11][12]

The nail bed extends from the distal margin of the lunula to the hyponychium, a space between the distal ridge and the nail plate. The nail bed matrix is located under the keratogenous zone of the nail plate matrix, obstructed from view by the lunula, and produces the nail bed epidermis. The onychodermal band is the name given to the distal margin of the nail bed, where a brown transverse band is present, which varies in color based on ethnicity.[13] The nail isthmus is a newly defined transitional zone between the distal nail bed and the hyponychium, postulated to serve as an anchor for the inferior nail plate and provide protection from trauma and injury by keratin production.[14]

Vascular Supply of the Nail Unit

The arterial supply of the fingers and toes is broadly similar. In the upper extremity, the radial and ulnar arteries supply deep and superficial palmar arcades that act as extensive anastomoses.[15] Branches aligned with the phalanges extend from these arcades, with 4 arteries supplying each digit (2 on either side). The dorsal digital arteries are small and branch off from the radial artery, forming anastomoses with the superficial and deep palmar arches and the palmar digital vessels before passing distally into the digit. The palmar digital arteries constitute the main blood vascular supply to the digits and receive contributions from both the deep and superficial palmar arcades.[11] They anastomose via dorsal and palmar arches around the distal phalanx. The palmar arch is located beneath the maximal padding of the finger pulp, and the dorsal nail fold arch (superficial arcade) lies just distal to the distal interphalangeal joint, where its tortuous path supplies the nail fold and nail plate matrix via branches.[16]

The venous drainage of the fingers is through deep and superficial systems, with the former corresponding to the arterial supply. The nail fold capillary network is like the normal cutaneous plexus, though the capillary loops are more horizontal and visible throughout their length.[17][18] The loops are arranged in tiers of uniform size, with their peaks equidistant from the base of the cuticle, the layer of skin at the proximal edge of the lunula.[11]

Glomus bodies are thermoregulatory plexuses of cavernous blood vessels and smooth muscle cells. They are constituted by an arteriovenous anastomosis that includes the afferent artery and the Sucquet-Hoyer canal, surrounded by epithelioid cells, smooth muscle cells, nervous supply, and an efferent vein, which connect outside the glomus capsule. The nail bed is richly supplied with glomus bodies, presumed to function in thermoregulation.[19][20][21] For instance, upon cold exposure, the arterioles constrict, and glomus bodies dilate, thereby ensuring the maintenance of the vascular supply to the peripheries.

Nerve Supply of the Nail Unit

The periungual soft tissues are innervated by the dorsal branches of paired digital nerves, with the palmar and plantar surfaces supplied by corresponding palmar and plantar nerve branches.[15] This innervation includes the digit pulp and extends up to the margin with the hyponychium.[11]

Histology of the Nail Unit

The nail plate is characterized by a modified stratum corneum.[22] The keratinized structure consists of compact, well-differentiated, flattened, and enucleated keratinocytes.[23] The nail plate matrix has thick stratified squamous epithelium with long rete ridges and the absence of a granular layer; as it approaches the lunula, it becomes abruptly thin. The loss of nuclei of the matrical keratinocytes in the eosinophilic keratogenous zone forms the lamina of the nail plate. The matrix is the sole subungual location of functioning melanocytes, which have a basal and suprabasal distribution and is the location of Langerhans cells and Merkel cells.[24][25] The matrical dermis contains a thin papillary and thick reticular layer. The hypodermis is composed of adipocytes with loose connective tissue, large vessels, and nerves; the matrical hypodermis is continuous with the proximal nail fold hypodermis, becoming less dense toward the nail bed.

The nail bed epithelium is composed of a monocellular basal layer and a spinous layer. Scant melanocytes with a basal distribution may be present.[26] The nail bed dermis consists of a singular compartment of collagen and elastic fibers, including glomus bodies and a longitudinally suspended rich vascular network. The proximal nail fold has 2 surfaces.[27] The dorsal surface is an extension of the finger epidermis, and its ventral surface overlies the proximal nail plate, the most distal of which is the eponychium.[28] At the angle between the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the proximal nail fold, the eponychium produces the cuticle, a thick stratum corneum layer that firmly adheres to the nail plate.[29] The lateral nail folds resemble normal skin except for their lack of pilosebaceous units.

The hyponychium refers to the epidermis underlying the free margin of the nail. Histologically, the hyponychium shows thick epithelium, including the stratum granulosum and basal melanocytes. The isthmus is the transitional zone between the distal nail bed and the hyponychium. This area is characterized by longitudinal ridges (similar to the nail bed), a discontinuous and thin granular layer, a thin compartment of pale corneocytes, and transitional keratin expression.[14] The nail isthmus is almost invisible in the normal nail, but it seems to have clinical significance in sealing the undersurface of the nail plate, preventing onycholysis; as such, it is implicated in diseases such as pterygium inversum unguis and ectopic nail.[30][31]

Dermoscopic Correlation with Anatomy, Physiology, and Histology of the Nail Unit

At lower magnification, the nail folds appear pale pink with a smooth surface, and the cuticle is a transparent, transverse band that seals the nail plate to the proximal nail fold. At higher magnification, there are hairpin-shaped capillary vessels parallel to the skin surface. Nailfold capillaries are best visualized with polarized video-dermatoscopes on the fourth or fifth digits (as these have the thinnest nail folds).[32] The nail plate appears pale pink with a smooth, shiny surface, though some longitudinal striations are typical in older individuals.[33] The nail bed is challenging to visualize without polarized contact dermoscopy, where it appears pale pink with a whitish hue proximally and possibly dilated capillaries distally. The nail matrix is difficult to visualize under an intact nail plate and can be best seen during intraoperative onychoscopy.[34]

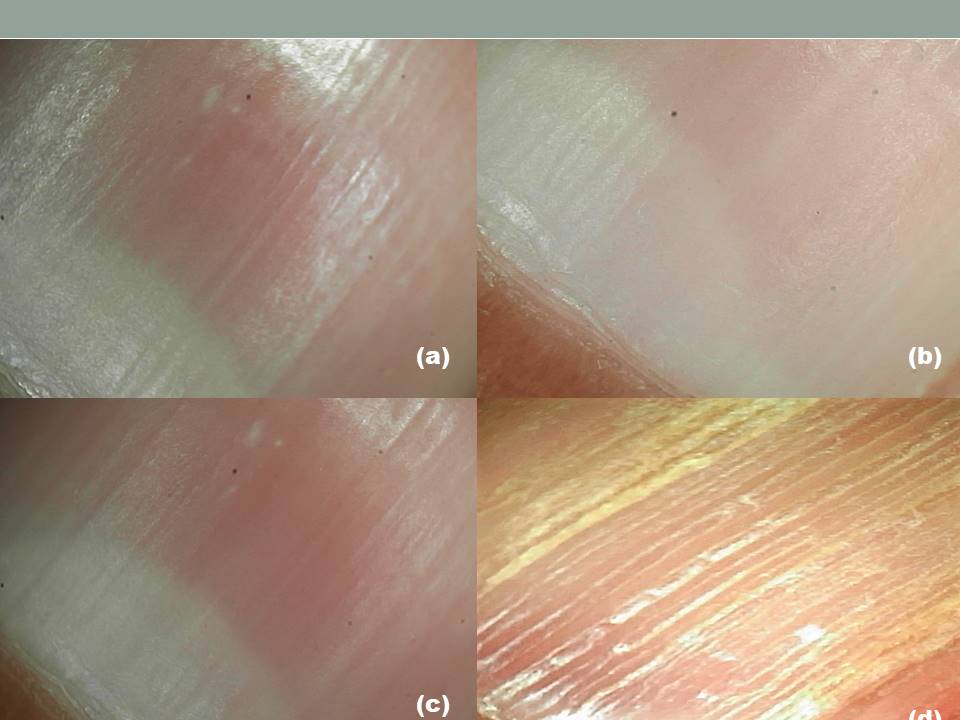

The hyponychium is best visualized using tangential dermoscopy, in which the dermatoscope is fixed at an angular slant (see Image. Tangential Dermoscopy, Hyponychium).[35] At lower magnification, onychoscopy of the hyponychium allows visualization of the distal nail plate, subungual space, and digital creases (see Image. Onychoscopy of the Hyponychium, Lower Magnification). Capillary architecture can be visualized at higher magnification, though this often requires video dermoscopy.[36] Nail fold capillaroscopy is of great diagnostic importance, as nail fold capillary architecture and density are important markers in connective tissue disorders.[17]

Indications

Onychoscopy is indicated for clinically diagnosing all nail unit pathologies and other systemic diseases manifesting nail involvement.[1] Evaluation of the nail with onychoscopy should be performed for disorders of pigmentation, infection, inflammatory diseases, connective tissue diseases, tumors, and trauma.[37]

Contraindications

Onychoscopy is safe for all individuals. Special care and attention should be paid to situations where nails are fragile or damaged or where the transfer of infections, such as COVID-19, is possible during the examination.[38][39]

Equipment

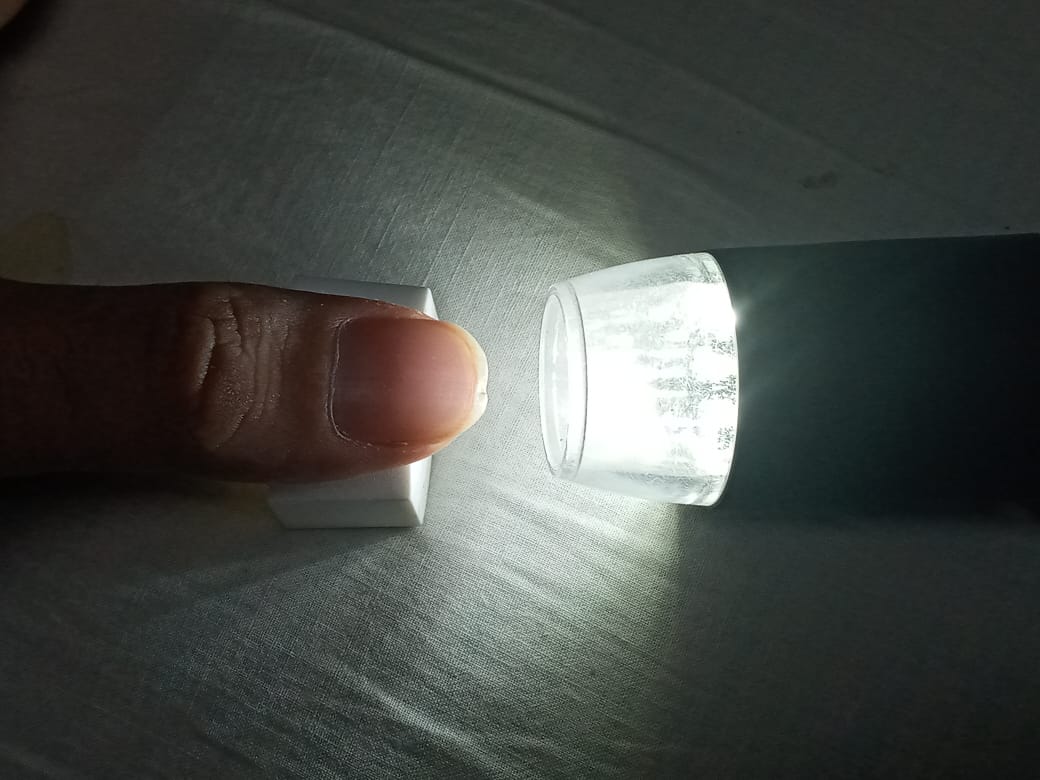

A dermatoscope is required for onychoscopy. For certain types of onychoscopy, alcohol wipes and a contact medium (such as ultrasound gel) may be required.[40] Modern handheld dermatoscopes can switch between polarized and nonpolarized settings; if not, separate dermatoscopes for each function are available. Handheld dermatoscopes may be combined with digital cameras or smartphones to capture images or videos (see Image. Dermatoscope, Handheld and Video). Nail plate changes such as pits, scales, surface irregularities, or matrix diseases are appreciated well with noncontact onychoscopy. In contrast, nail bed changes, color abnormalities, onycholysis, and changes in the distal nail margin are better visualized by contact onychoscopy. For optimal vasculature evaluation, the hand should be at the level of the heart, and average ambient temperatures should be maintained.[41]

Personnel

Any trained healthcare professional can perform an onychoscopy using a dermatoscope. Onychoscopy is particularly valuable in dermatology, rheumatology, infectious diseases, and primary care, where nail disorders are frequently encountered.[42]

Preparation

Both nonpolarized and polarized light dermatoscopes are utilized in onychoscopy. To minimize or eliminate surface reflectance, the difference in refractive indices between air and the stratum corneum must be addressed.[32] This reduction in reflectance can be accomplished by using a polarized dermoscope, adjusting the dermoscope at a tangential angle, and applying an interface medium. Various interface media have been used during onychoscopy, such as antiseptic gels (eg, alcohol), water-based gels (eg, ultrasound gel), or oils (eg, mineral oil). Among these, ultrasound gel is preferred owing to its decreased viscosity, which allows it to stay in contact with the nail plate and fill up the concavities.[43] While performing onychoscopy, keeping the digit gently on a flat hard surface is recommended, avoiding any undue pressure.

Technique or Treatment

First, the nail should be cleansed by having the patient wash their hands if there is visible debris on the hands and nails. Additional cleansing with alcohol (or acetone, in some cases with nail polish) may be required to ensure the appropriate ability to examine the nails.[44] The dermatoscope should be focused on each use per the manufacturer's guidelines, such that the examined portion is focused and the eyepiece is used for visualization. The dermatoscope is usually kept vertical while examining the nail plate but needs to be tilted to examine the distal free edge of the nail plate. The dermatoscope must be moved transversally and back and forth to visualize different parts of the nail unit since the whole nail plate may not be visible in 1 field. Noncontact onychoscopy should be performed before contact onychoscopy, in which the interface medium increases nail plate transparency and light penetration.

Dermoscopy with nonpolarized light ensures better visualization of surface irregularities, such as pits and ridges, whereas polarized light blunts surface irregularities and enables visualization of deeper structures, such as nail bed details. An interface or immersion medium, usually ultrasound gel, is recommended to visualize the nail apparatus better. Transillumination can be used to evaluate the extent of a nail tumor, such as a glomus tumor.[45] In intraoperative onychoscopy, the dermatoscope guides biopsy with the avulsed or partially removed nail plate.[46] Start examining the nail unit with low magnification (10X) initially, which allows visualization of the whole nail unit, then higher magnification (up to 100X), depending upon the characteristic features to be appreciated. Compared to dermoscopy, onychoscopy is technically challenging due to the nail size, shape, convexity, and firmness.

Complications

There are minimal complications with onychoscopy, though care is necessary to prevent cross-contamination of the glass covering between patients to prevent infection. This is easily achieved by using alcohol or disposable lens coverings to wipe the lens.

Clinical Significance

Onychoscopy is a valuable diagnostic tool that allows for noninvasive examination of the nail unit, aiding in the early detection of various nail disorders; its ability to reveal subtle changes in nail structure enhances diagnostic accuracy, reducing the need for invasive procedures and improving patient outcomes. Evaluation of the nail with onychoscopy should be performed for disorders of pigmentation, infection, inflammatory diseases, connective tissue diseases, tumors, and trauma.

Pigmentation

The archetypal pigmentation lesion is longitudinal melanonychia, where pigmentation is usually located longitudinally in the nail plate, though it can be transverse. Melanonychia is first evaluated by establishing if the pigment is melanotic or non-melanotic (eg, blood). Next, if melanotic, it must be determined if the etiology is matrical melanocytic activation or proliferation; if determined to be due to proliferation, it must be established as either benign or malignant.[3][47][48] Melanocytic activation is common in darker skin types and various disorders, such as lichen planus, drug-related conditions (eg, antimalarials), postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, traumatic melanonychia, or as part of a benign pigmentary lesion such as lentigo.[3] Longitudinal pigmented bands due to melanocytic activation are polydactylic and appear as thin gray bands under the dermatoscope. Melanocytic proliferation often appears as a brown or black monodactylic band. Benign melanocytic proliferation, such as in a benign nail matrix nevus, is visualized as a single band with color and thickness uniformity.[49] Benign melanocytic proliferation may not demonstrate a regular pattern, especially in children, where an opaque roughness of the nails may be present and has been linked with alopecia areata.[26][50]

Malignant melanocytic proliferation, such as in nail matrix melanoma, often demonstrates a brown or black band that may show irregularities in color, parallelism, spacing, and thickness; melanoma may also present as diffuse darkness with barely visible lines. Variability in hues may point out the possibility of melanoma.[51] Rarely melanoma is found to be associated with Bowen disease or squamous cell carcinoma.[52] Additional dermoscopic features of squamous cell carcinoma include an absence of normal dermatoglyphics, red-dotted vessels, and white scales.[53] Proximal nail fold or hyponychium pigmentation can indicate melanoma, called the micro-Hutchinson sign, when invisible to the naked eye and visible on dermoscopy. However, the Hutchinson sign may also be seen in benign melanocytic proliferation, for which further diagnostic evaluation may be required.[54] Onychoscopy of longitudinal melanonychia at the free edge can aid in identifying the origin of the pigment.[49][55] Ventral pigmentation originates from the distal matrix, and dorsal pigmentation originates from the proximal matrix, which can aid in biopsy site selection.[51]

Non-melanotic pigmentation is usually due to subungual hematoma or infection. Subungual hematoma has reddish-purple to black lesions with well-circumscribed reddish dots or streaks at the distal edge in the acute phase and splinter hemorrhages with a linear pattern in the chronic phase.[56] However, if the hematoma does not resolve with nail growth, a wider differential of melanotic pigmentation should be considered. Pseudomonal infection can cause green or green-black pigmentation due to colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which produces the pyocyanin pigment, which attaches to the irregular nail undersurface.[57] Central homogenous pigmentation (ie, not longitudinal) may be seen with exogenous nail pigmentation due to dyes (to be distinguished from endogenous pigmentation of melanin or hemosiderin, such as in melanoma).[54]

Leukonychia must be classified as true, apparent, or pseudo-leukonychia. In true leukonychia, altered keratinization of the distal nail matrix produces white pigmentation in the nail plate. In contrast, the discoloration originates in the nail bed in apparent leukonychia and has an external origin in pseudo-leukonychia. True leukonychia from repetitive trauma often presents with transverse or punctate white marks that move distally as the nail grows.[58] Onychoscopy of true leukonychia demonstrates a smooth, transparent nail plate with 1 or more white dots or longitudinal bands. In transverse leukonychia, white lines appear to run horizontally parallel to the proximal nail fold, and the space between each transverse band indicates the interval between traumas.

A white discoloration of the lunula is typical of proximal subungual onychomycosis.[59] Small white-to-yellow opaque and friable patches may be seen in superficial onychomycosis. Keratosis follicularis (ie, Darier disease) and benign familial pemphigus (ie, Hailey-Hailey disease) may also present with multiple alternating red and white bands; this can often be confused with longitudinal leukonychia, often associated with onychopapilloma.[60][61] Erythronychia describes red nail discoloration and can often be seen in many benign tumors, where the corresponding nail plate may show fissures or a subungual mass.[62]

Infections

Onychoscopy plays an important role in diagnosing onychomycosis; after all, onychoscopic-guided sampling can help provide the best yield for microbiologic evaluation.[63][64] In distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, the nail plate has whitish-yellow discoloration; dermoscopy shows white-yellow longitudinal striations in the nail plate from the distal free edge toward the proximal nail fold.[65] This is believed to be the fungus's linear progression proximally over the nail bed's rete ridges. Of note, it has been suggested that involvement of over half of the nail plate or involvement of the lunula in these striations should require oral, rather than topical, treatment with antifungals, a practical consideration when viewing the onychomycotic nail with dermoscopy.[66][67][68][69]

Onycholysis is often seen in onychomycosis as a jagged nail plate edge with intermittent spikes, but onycholysis can have other causes, such as nail psoriasis and trauma.[70] The onycholytic nail plate may also show a pattern termed the aurora borealis, a variegated streak on the nail plate with parallel bands of varying colors.[71] However, in psoriatic or traumatic onycholysis, the proximal border is smooth, in contrast to onychomycosis.[72] Furthermore, there is a band of erythema proximal to the onycholytic margin in psoriatic nails, and traumatic onycholysis is often accompanied by splinter hemorrhages or subungual hematoma.[73] Trauma can also be local, such as if a digital myxoid cyst were to penetrate the subungual space, where dermoscopy may show the keratotic plug of the cyst.[74]

Although often presenting as a white-yellow streak, onychomycosis can present as longitudinal or transverse melanonychia, where fungal colonies clump into pigmented granules in the bands.[75] The inverted triangle sign is one where the width of the band is broader distally and narrower proximally; this is to be differentiated from nail unit melanoma, where pigmentation is broader proximally, corresponding to melanocytic proliferation more proximally.[75][76] Subungual hyperkeratosis, commonly observed in onychomycosis, corresponds to indented and crumbled areas of the nail.[77] However, it should not be mistaken for the whitish-gray hyperkeratotic lesions of subungual warts, distinguishable by thrombosed vessels appearing as red or black dots on onychoscopy, similar to those seen in cutaneous warts.[78]

Inflammatory Diseases

Onychoscopy has markedly improved the visualization of minute features in nail psoriasis.[79] Nail pitting, splinter hemorrhages, and onycholysis are the most common findings encountered across multiple studies.[80][81] Ultimately, the involvement of the nail matrix results in large, deep, irregularly arranged pits (versus the small, shallow, and regularly arranged pits in alopecia areata) grossly. Leukonychia is also often present. The involvement of the nail bed results in onycholysis, salmon patches, splinter hemorrhages, and subungual hyperkeratosis.[81]

Onycholysis has a distinct erythematous or bright yellow-orange border at the proximal end of the onycholytic band, which is relatively straight. In psoriasis, pitting of the nails and splinter hemorrhages have been observed as the most common feature, followed by onycholysis.[80][81] The oil drop sign or salmon patch is an irregularly shaped red-orange patch present in nail psoriasis.[82] The splinter hemorrhages appear as bright red to blackish longitudinal fusiform streaks.[82][83] The nail bed compact hyperkeratosis in psoriasis is unique compared with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis.[12]

Onychoscopic examination of the proximal nail fold reveals a reduced mean capillary count and architectural alterations, including coiled capillaries and dropouts. On onychoscopic examination of the hyponychium, irregularly distributed, elongated, tortuous, and dilated capillaries are observed, similar to those seen in psoriasis of the skin. The capillary density correlates directly with the severity of disease and treatment response. In some cases, the capillaries, which appear as red dots, can be visible on the proximal nail fold.[3]

Onychoscopy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis has demonstrated tortuous capillaries with dilated loops, a normal number of capillaries, and no hemorrhagic spots. However, 1 study does report findings of angiogenesis being common.[84][85] Onychoscopy has also aided in the evaluation of lichen planus, where involvement of the nails is seen.[86][87] The limited studies of onychoscopy of lichen planus have shown the involvement of the nail matrix may result in pitting, pterygium, trachyonychia, and red lunulae. In contrast, the involvement of the nail bed may result in chromonychia, onycholysis, subungual keratosis, nail fragmentation, splinter hemorrhages, and longitudinal streaks.[86][88]

Connective Tissue Diseases

Connective tissue diseases benefit from onychoscopy in the evaluation of nail fold capillaries. Capillaroscopy may also serve as a valuable tool in systemic diseases to predict the development of visceral complications and digital ulceration.[89] This is paramount in the disorders described here, including systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

In systemic sclerosis, the nail fold capillary destruction occurs secondary to vasculopathy and microangiopathy.[90] Few giant capillaries with irregularly enlarged capillaries and hemorrhages are seen in early disease. In active disease, capillary architecture is usually disordered with mild capillary dropout and dilated capillary loops. In late disease, the architecture of capillaries is disorganized with severe loss of capillaries along with avascular areas and few, giant, and ramified capillaries.[91] Because sclerotic changes can be delayed, onychoscopic examination may aid in early diagnosis.

A prominent subpapillary plexus with tortuous capillaries is seen in systemic lupus erythematosus.[92] However, in other studies, meandering capillaries have been seen, while some studies have pointed at a normal, nondiagnostic appearance of the nail fold capillaries compared to systemic sclerosis.[89][92] Mixed connective tissue disease is similar to systemic sclerosis on onychoscopy, observed in up to 50% of patients.[93] Rowell syndrome is a rare autoimmune disease with lupus erythematosus, erythema multiforme-like lesions, and immunologic serum abnormalities (eg, speckled antinuclear antibody pattern); nail capillary changes in Rowell syndrome show multiple hemorrhagic spots and dilated capillary loops.[94]

In dermatomyositis, nail fold capillaries are grossly enlarged with tortuous, dilated capillary loops and multiple hemorrhagic spots; prognostically, this finding correlates with myalgias and arthralgias.[95] Bushy or budding capillaries and avascular areas representing revascularization or ischemia are frequently seen, similar to those in systemic sclerosis.[96][97] Therefore, based on the nail fold capillary findings observed on onychoscopy, dermatomyositis, and polymyositis may be distinguishable based on nail fold capillary changes.

Tumors

Onychopapilloma is a benign neoplasm of the distal matrix/proximal nail bed. Onychoscopy shows a band of longitudinal erythronychia from the lunula to the distal margin, often associated with splinter hemorrhages.[98] Onychoscopy shows a characteristic keratotic subungual mass at the distal edge of the nail plate. The distal nail plate may show a subungual filiform hyperkeratotic mass and a fissure; if associated with onycholysis, these findings may suggest a larger tumor.[98]

A glomus tumor is a benign vascular hamartoma of the glomus body arising from the thermoregulatory smooth muscle cells.[99][100] The tumor often presents with severe paroxysmal pain, cold sensitivity, and pinpoint tenderness.[101] On onychoscopy, the tumor mass can be visualized as a deep reddish-purple discoloration along with blurred borders and discrete linear vascular structures or as longitudinal erythronychia that usually does not reach the distal margin.[99] After removal of the nail plate during intraoperative onychoscopy, ramified capillaries over a blue background have been seen; since these ramified capillaries disappear abruptly at the margins, this finding may be typically useful for determining the margins of tumors.[62][99][102] With the use of ultraviolet light dermoscopy, a pink glow has been described, indicating the vascular nature of the tumor.[103]

Onychomatricoma is a rare matrix tumor that is usually benign and presents with a classical tetrad of ungual hyperkeratosis, splinter hemorrhages, xanthonychia, and over curvature of the nail plate, both transversely and longitudinally. On dermoscopy, it often has parallel lateral edges, nail pitting, thickening of the free edge, dark dots, splinter hemorrhages, and longitudinal parallel white lines.[104][105] Pyogenic granuloma, on onychoscopy, shows a vascular pattern with reddish discoloration and regular vessels (which appear as dots at low magnification and lines at higher magnification) with a milky red veil.[106][107] At the center of the lesion, the red is generally darker; at the periphery of the lesion, the red is conversely paler.

Trauma

Nail tic disorders, such as onychotillomania, show characteristic features like the absence of the nail plate with multiple obliquely oriented nail bed hemorrhages, gray pigmentation of the nail bed, and the presence of wavy lines—uneven longitudinal pigmented lines in different planes due to uneven or absent nail plate growth after recurring trauma.[108][109]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing patient-centered care, outcomes, safety, and team performance in onychoscopy requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach. Each healthcare team member should possess specific skills related to onychoscopy. Clinicians must perform the procedure, identify key diagnostic features, and integrate the findings into clinical decision-making. Nurses should be skilled in preparing patients for onychoscopy, educating them about the procedure, and providing post-evaluation care. Pharmacists contribute by understanding the pharmacological management of nail disorders and ensuring appropriate treatment plans are followed.

Effective communication between team members is essential for enhancing care through onychoscopy. Clinicians must communicate findings clearly to the broader healthcare team, ensuring all professionals involved in the patient’s care are informed about the diagnosis and treatment plan. Regular case discussions and consultations help reinforce a collaborative environment where everyone clearly understands the patient’s status. A coordinated care plan should be developed, with clear follow-up procedures, ensuring the patient receives the appropriate care at each stage. This coordinated care reduces the risk of misdiagnosis and ensures patient safety by minimizing procedural complications. A team-based, interprofessional approach to onychoscopy improves patient outcomes by enhancing diagnostic accuracy, reducing the need for more invasive procedures, and ensuring timely treatment.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

This procedure should be used in all conditions involving the nail unit or suspected of having that involvement. Findings from this procedure should be integrated with interprofessional team members, including those in the clinical setting, pathology, and related specialties, such as Mohs micrographic surgery.[110]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

No monitoring is necessary during or after an onychoscopy. However, all team members play a role in ensuring hygienic practices, so appropriate nail cleansing, particularly after using an interface media, should be performed by having the patient wash their hands or use alcohol or other antimicrobial wipes.

Media

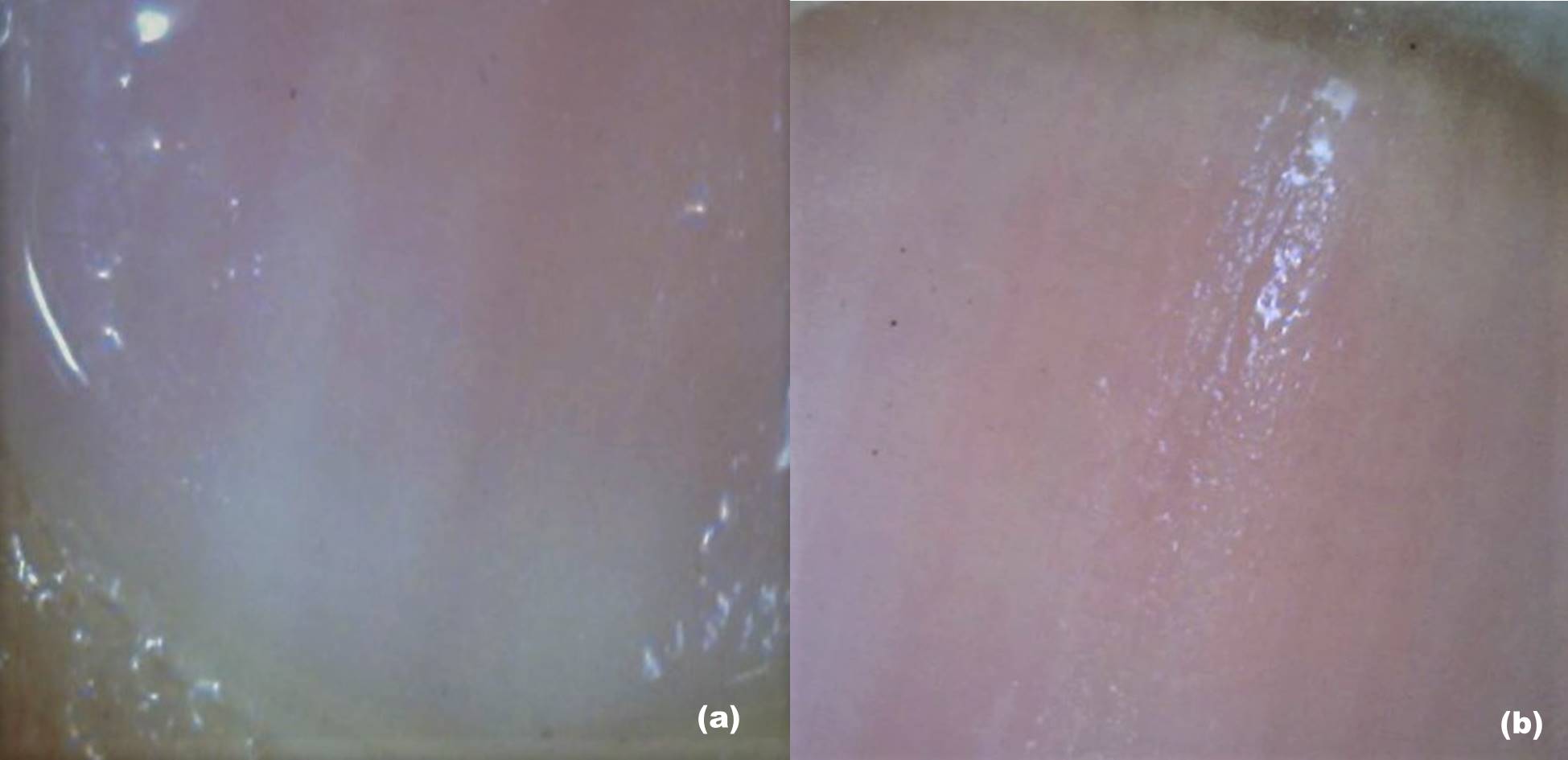

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Onychoscopy, Dermatologic Diagnosis. (A) The lower part of the nail plate and proximal nail fold, as seen during dry dermoscopy, is examined without an interface medium. (B) The lower part of the nail plate and proximal nail fold, as seen during wet dermoscopy, is examined with an interface medium. (C) The proximal nail fold shows the architecture of vessels at higher magnification [200×]. (D) The lateral part of the nail plate and nail fold, as seen during wet dermoscopy, is examined with an interface medium.

Contributed by S Sonthalia, MD

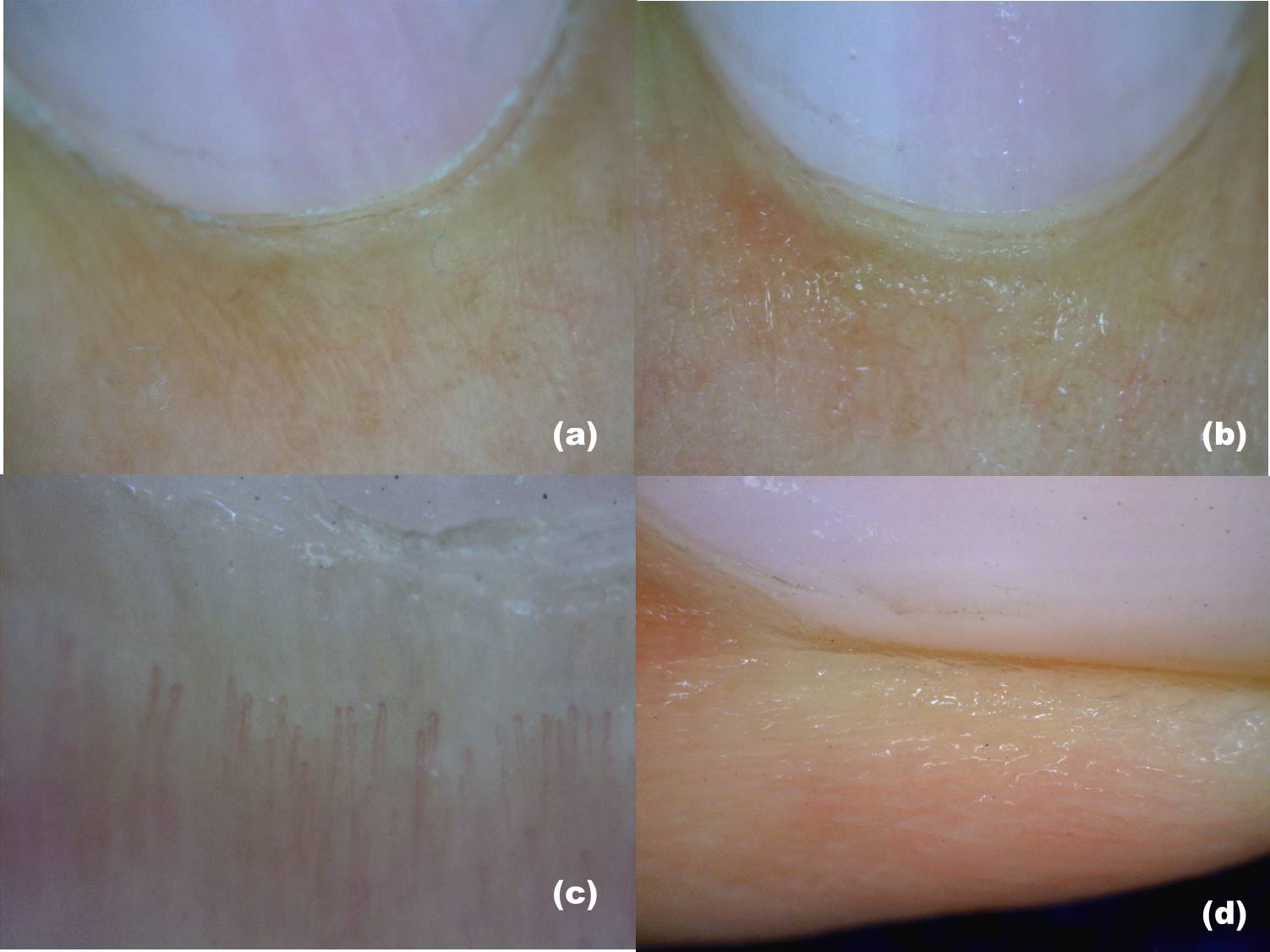

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Dermatoscope, Handheld and Video. (A) The nail plate is seen during dry dermoscopy (examined without an interface medium and handheld). (B) The nail plate is seen during wet dermoscopy (examined with an interface medium). (C) The nail plate is seen with video dermoscopy at lower magnification. (D) The nail plate, seen with video dermoscopy at higher magnification, shows the surface irregularities.

Contributed by S Sonthalia, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sonthalia S, Pasquali P, Agrawal M, Sharma P, Jha AK, Errichetti E, Lallas A, Sehgal VN. Dermoscopy Update: Review of Its Extradiagnostic and Expanding Indications and Future Prospects. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2019 Oct:9(4):253-264. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0904a02. Epub 2019 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 31723457]

Carlioz V, Perier-Muzet M, Debarbieux S, Amini-Adle M, Dalle S, Duru G, Thomas L. Intraoperative dermoscopy features of subungual squamous cell carcinoma: a study of 53 cases. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2021 Jan:46(1):82-88. doi: 10.1111/ced.14345. Epub 2020 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 32569407]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLencastre A, Lamas A, Sá D, Tosti A. Onychoscopy. Clinics in dermatology. 2013 Sep-Oct:31(5):587-93. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.06.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24079588]

Hirata SH, Yamada S, Almeida FA, Tomomori-Yamashita J, Enokihara MY, Paschoal FM, Enokihara MM, Outi CM, Michalany NS. Dermoscopy of the nail bed and matrix to assess melanonychia striata. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005 Nov:53(5):884-6 [PubMed PMID: 16243149]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDi Chiacchio ND, Farias DC, Piraccini BM, Hirata SH, Richert B, Zaiac M, Daniel R, Fanti PA, Andre J, Ruben BS, Fleckman P, Rich P, Haneke E, Chang P, Cherit JD, Scher R, Tosti A. Consensus on melanonychia nail plate dermoscopy. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2013 Mar-Apr:88(2):309-13. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962013000200029. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23739699]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIorizzo M, Rubin AI, Starace M. Nail lichen striatus: Is dermoscopy useful for the diagnosis? Pediatric dermatology. 2019 Nov:36(6):859-863. doi: 10.1111/pde.13916. Epub 2019 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 31359464]

Gao J, Fei W, Shen C, Shen X, Sun M, Xu N, Li Q, Huang C, Zhang T, Ko R, Cui Y, Yang C. Dermoscopic Features Summarization and Comparison of Four Types of Cutaneous Vascular Anomalies. Frontiers in medicine. 2021:8():692060. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.692060. Epub 2021 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 34262918]

Lake A, Jones B. Dermoscopy: to cross-polarize, or not to cross-polarize, that is the question. Journal of visual communication in medicine. 2015 Jun:38(1-2):36-50. doi: 10.3109/17453054.2015.1046371. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26203939]

Weber P, Tschandl P, Sinz C, Kittler H. Dermatoscopy of Neoplastic Skin Lesions: Recent Advances, Updates, and Revisions. Current treatment options in oncology. 2018 Sep 20:19(11):56. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0573-6. Epub 2018 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 30238167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePulawska-Czub A, Pieczonka TD, Mazurek P, Kobielak K. The Potential of Nail Mini-Organ Stem Cells in Skin, Nail and Digit Tips Regeneration. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021 Mar 11:22(6):. doi: 10.3390/ijms22062864. Epub 2021 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 33799809]

de Berker D. Nail anatomy. Clinics in dermatology. 2013 Sep-Oct:31(5):509-15. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.06.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24079579]

Haneke E. Nail psoriasis: clinical features, pathogenesis, differential diagnoses, and management. Psoriasis (Auckland, N.Z.). 2017:7():51-63. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S126281. Epub 2017 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 29387608]

TERRY RB. The onychodermal band in health and disease. Lancet (London, England). 1955 Jan 22:268(6856):179-81 [PubMed PMID: 13234317]

Oiso N, Kurokawa I, Kawada A. Nail isthmus: a distinct region of the nail apparatus. Dermatology research and practice. 2012:2012():925023. doi: 10.1155/2012/925023. Epub 2012 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 22454634]

Baltz JO, Jellinek NJ. Nail Surgery: Six Essential Techniques. Dermatologic clinics. 2021 Apr:39(2):305-318. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2020.12.015. Epub 2021 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 33745642]

Papaioannou I, Pantazidou G, Repantis T, Mousafeiris VK, Kalyva N. Late-Onset Hematoma Due to Bleeding of a Small Branch of the Lateral Circumflex Femoral Artery Following Proximal Femur Intramedullary Nailing. Cureus. 2022 Mar:14(3):e23513. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23513. Epub 2022 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 35495014]

Grover C, Jakhar D, Mishra A, Singal A. Nail-fold capillaroscopy for the dermatologists. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2022 May-Jun:88(3):300-312. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_514_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34877857]

Lambova SN, Müller-Ladner U. The specificity of capillaroscopic pattern in connective autoimmune diseases. A comparison with microvascular changes in diseases of social importance: arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Modern rheumatology. 2009:19(6):600-5. doi: 10.1007/s10165-009-0221-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19779765]

Shinohara T, Hirata H. Glomus Tumor Originating from a Digital Nerve. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2019 Jun:7(6):e2053. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002053. Epub 2019 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 31624656]

Lee JK, Kim TS, Kim DW, Han SH. Multiple glomus tumours in multidigit nail bed. Handchirurgie, Mikrochirurgie, plastische Chirurgie : Organ der Deutschsprachigen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Handchirurgie : Organ der Deutschsprachigen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Mikrochirurgie der Peripheren Nerven und Gefasse : Organ der V.... 2017 Oct:49(5):321-325. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-115115. Epub 2017 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 29041022]

Kumar S, Tiwary SK, More R, Kumar P, Khanna AK. Digital glomus tumor: An experience of 57 cases over 20 years. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2020 Jul:9(7):3514-3517. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_446_20. Epub 2020 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 33102323]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGüneş P, Göktay F. Melanocytic Lesions of the Nail Unit. Dermatopathology (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Jul-Sep:5(3):98-107. doi: 10.1159/000490557. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30197884]

Brahs AB, Bolla SR. Histology, Nail. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969555]

Prevezas C, Triantafyllopoulou I, Belyayeva H, Sgouros D, Konstantoudakis S, Panayiotides I, Rigopoulos D. Giant Onychomatricoma of the Great Toenail: Case Report and Review Focusing on Less Common Variants. Skin appendage disorders. 2016 May:1(4):202-8. doi: 10.1159/000445386. Epub 2016 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 27386467]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePerrin C, Baran R, Pisani A, Ortonne JP, Michiels JF. The onychomatricoma: additional histologic criteria and immunohistochemical study. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2002 Jun:24(3):199-203 [PubMed PMID: 12140434]

Ríos-Viñuela E, Manrique-Silva E, Nagore E, Nájera-Botello L, Requena L, Requena C. Subungual Melanocytic Lesions in Pediatric Patients. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2022 Apr:113(4):388-400. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2021.10.007. Epub 2021 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 35623729]

Güldiken G, Göktay F, Atış G, Güneş P. Evaluation of the Demographic and Clinical Features of Patients With Digital Myxoid Pseudocysts and Their Response to Treatment. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Jun 1:48(6):625-630. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003433. Epub 2022 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 35333205]

Bae TH, Kim HS, Lee JS. Eponychial flap elevation method for surgical excision of a subungual glomus tumor. Dermatologic therapy. 2020 Nov:33(6):e14330. doi: 10.1111/dth.14330. Epub 2020 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 32975348]

Shin JO, Roh D, Son JH, Shin K, Kim HS, Ko HC, Kim BS, Kim MB. Onychophagia: detailed clinical characteristics. International journal of dermatology. 2022 Mar:61(3):331-336. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15861. Epub 2021 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 34416026]

Oiso N, Narita T, Tsuruta D, Kawara S, Kawada A. Pterygium inversum unguis: aberrantly regulated keratinization in the nail isthmus. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2009 Oct:34(7):e514-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03601.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19747338]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOiso N, Kurokawa I, Tsuruta D, Narita T, Chikugo T, Tsubura A, Kimura M, Baran R, Kawada A. The histopathological feature of the nail isthmus in an ectopic nail. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2011 Dec:33(8):841-4. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181f96bce. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21885945]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStarace M, Alessandrini A, Piraccini BM. Dermoscopy of the Nail Unit. Dermatologic clinics. 2021 Apr:39(2):293-304. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2020.12.008. Epub 2021 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 33745641]

Lee DK, Lipner SR. Optimal diagnosis and management of common nail disorders. Annals of medicine. 2022 Dec:54(1):694-712. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2044511. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35238267]

Lee DK, Chang MJ, Desai AD, Lipner SR. Clinical and dermoscopic findings of benign longitudinal melanonychia due to melanocytic activation differ by skin type and predict likelihood of nail matrix biopsy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022 Oct:87(4):792-799. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1165. Epub 2022 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 35752275]

Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, Liu J, Huang FR, Wang DG. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: Evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Sep:81(3):717-722. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065. Epub 2019 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 30930088]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDellatorre G, Gadens GA, Polo Silveira L, Kose K, Marghoob AA. Video-based wide area digital dermoscopy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022 Oct:87(4):e125-e126. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.842. Epub 2021 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 34146617]

Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A, Starace M. Onychoscopy: Dermoscopy of the Nails. Dermatologic clinics. 2018 Oct:36(4):431-438. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.05.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30201152]

Campos-do-Carmo G, Ramos-e-Silva M. Dermoscopy: basic concepts. International journal of dermatology. 2008 Jul:47(7):712-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03556.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18613881]

Jakhar D, Kaur I, Kaul S. Art of performing dermoscopy during the times of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): simple change in approach can save the day! Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2020 Jun:34(6):e242-e244. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16412. Epub 2020 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 32223004]

González Cortés LF, Prada L, Bonilla JD, Gómez Lopez MT, Rueda LJ, Ibañez E. Onychoscopy in a Colombian population with a diagnosis of toenail onychomycosis: an evaluation study for this diagnostic test. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2021 Dec:46(8):1427-1433. doi: 10.1111/ced.14706. Epub 2021 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 33899948]

Pan Y, Gareau DS, Scope A, Rajadhyaksha M, Mullani NA, Marghoob AA. Polarized and nonpolarized dermoscopy: the explanation for the observed differences. Archives of dermatology. 2008 Jun:144(6):828-9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.6.828. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18559791]

Hazarika N, Chauhan P, Divyalakshmi C, Kansal NK, Bahurupi Y. Onychoscopy: a quick and effective tool for diagnosing onychomycosis in a resource-poor setting. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica. 2021 Mar:30(1):11-14 [PubMed PMID: 33765751]

Tasli L, Oguz O. The role of various immersion liquids at digital dermoscopy in structural analysis. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2011 Jan-Feb:77(1):110. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.74981. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21220902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGrover C, Jakhar D. Onychoscopy: A practical guide. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2017 Sep-Oct:83(5):536-549. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_242_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28485306]

Jakhar D, Kaur I. Transillumination dermoscopy for nail bed pathology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Sep:85(3):e137-e138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.045. Epub 2017 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 29288098]

Di Chiacchio N, Hirata SH, Enokihara MY, Michalany NS, Fabbrocini G, Tosti A. Dermatologists' accuracy in early diagnosis of melanoma of the nail matrix. Archives of dermatology. 2010 Apr:146(4):382-7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.27. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20404227]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTosti A, Piraccini BM, de Farias DC. Dealing with melanonychia. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2009 Mar:28(1):49-54. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19341943]

Kungvalpivat P, Rojhirunsakool S, Chayavichitsilp P, Suchonwanit P, Wichayachakorn CT, Rutnin S. Clinical and Onychoscopic Features of Benign and Malignant Conditions in Longitudinal Melanonychia in the Thai Population: A Comparative Analysis. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2020:13():857-865. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S283112. Epub 2020 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 33244251]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKawabata Y, Ohara K, Hino H, Tamaki K. Two kinds of Hutchinson's sign, benign and malignant. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001 Feb:44(2):305-7 [PubMed PMID: 11174394]

Starace M, Alessandrini A, Bruni F, Piraccini BM. Trachyonychia: a retrospective study of 122 patients in a period of 30 years. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2020 Apr:34(4):880-884. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16186. Epub 2020 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 31923322]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBraun RP, Baran R, Saurat JH, Thomas L. Surgical Pearl: Dermoscopy of the free edge of the nail to determine the level of nail plate pigmentation and the location of its probable origin in the proximal or distal nail matrix. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006 Sep:55(3):512-3 [PubMed PMID: 16908362]

Baran R, Simon C. Longitudinal melanonychia: a symptom of Bowen's disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1988 Jun:18(6):1359-60 [PubMed PMID: 3385047]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGiacomel J, Lallas A, Zalaudek I, Argenziano G. Periungual Bowen disease mimicking chronic paronychia and diagnosed by dermoscopy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014 Sep:71(3):e65-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.894. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25128126]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBraun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, Dalle S, Ronger S, Pandolfi R, Gaide O, French LE, Laugier P, Saurat JH, Marghoob AA, Thomas L. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007 May:56(5):835-47 [PubMed PMID: 17320240]

Iorizzo M, Starace M, Di Altobrando A, Alessandrini A, Veneziano L, Piraccini BM. The value of dermoscopy of the nail plate free edge and hyponychium. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2021 Dec:35(12):2361-2366. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17521. Epub 2021 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 34255894]

Sato T, Tanaka M. The reason for red streaks on dermoscopy in the distal part of a subungual hemorrhage. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2014 Apr:4(2):83-5. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0402a18. Epub 2014 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 24855582]

Chiriac A, Brzezinski P, Foia L, Marincu I. Chloronychia: green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in elderly persons. Clinical interventions in aging. 2015:10():265-7. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S75525. Epub 2015 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 25609938]

Baran R, Perrin C. Transverse leukonychia of toenails due to repeated microtrauma. The British journal of dermatology. 1995 Aug:133(2):267-9 [PubMed PMID: 7547396]

Yorulmaz A, Yalcin B. Dermoscopy as a first step in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. 2018 Jun:35(3):251-258. doi: 10.5114/ada.2018.76220. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 30008642]

Bhat YJ, Mir MA, Keen A, Hassan I. Onychoscopy: an observational study in 237 patients from the Kashmir Valley of North India. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2018 Oct:8(4):283-291. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0804a06. Epub 2018 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 30479856]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBel B, Jeudy G, Vabres P. Dermoscopy of longitudinal leukonychia in Hailey-Hailey disease. Archives of dermatology. 2010 Oct:146(10):1204. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.226. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20956678]

Göktay F, Güldiken G, Altan Ferhatoğlu Z, Güneş P, Atış G, Haneke E. The role of dermoscopy in the diagnosis of subungual glomus tumors. International journal of dermatology. 2022 Jul:61(7):826-832. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16042. Epub 2022 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 35073425]

Bet DL, Reis AL, Di Chiacchio N, Belda Junior W. Dermoscopy and Onychomycosis: guided nail abrasion for mycological samples. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2015 Nov-Dec:90(6):904-6. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20154615. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26734877]

Jesús-Silva MA, Fernández-Martínez R, Roldán-Marín R, Arenas R. Dermoscopic patterns in patients with a clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis-results of a prospective study including data of potassium hydroxide (KOH) and culture examination. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2015 Apr:5(2):39-44. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0502a05. Epub 2015 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 26114050]

De Crignis G, Valgas N, Rezende P, Leverone A, Nakamura R. Dermatoscopy of onychomycosis. International journal of dermatology. 2014 Feb:53(2):e97-9. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12104. Epub 2013 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 23786765]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePiraccini BM, Starace M, Rubin AI, Di Chiacchio NG, Iorizzo M, Rigopoulos D, A working group of the European Nail Society. Onychomycosis: Recommendations for Diagnosis, Assessment of Treatment Efficacy, and Specialist Referral. The CONSONANCE Consensus Project. Dermatology and therapy. 2022 Apr:12(4):885-898. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00698-x. Epub 2022 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 35262878]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta AK, Cooper EA. Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophytosis. Mycopathologia. 2008 Nov-Dec:166(5-6):353-67. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9109-0. Epub 2008 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 18478357]

de Berker D. Clinical practice. Fungal nail disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 May 14:360(20):2108-16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804878. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19439745]

Murdan S. Drug delivery to the nail following topical application. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2002 Apr 2:236(1-2):1-26 [PubMed PMID: 11891066]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZaias N, Escovar SX, Zaiac MN. Finger and toenail onycholysis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2015 May:29(5):848-53. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12862. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25512134]

Bodman MA. Point-of-Care Diagnosis of Onychomycosis by Dermoscopy. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2017 Sep:107(5):413-418. doi: 10.7547/16-183. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29077504]

Ankad BS, Gupta A, Alekhya R, Saipriya M. Dermoscopy of Onycholysis Due to Nail Psoriasis, Onychomycosis and Trauma: A Cross Sectional Study in Skin of Color. Indian dermatology online journal. 2020 Sep-Oct:11(5):777-783. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_475_19. Epub 2020 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 33235845]

Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, Rech G. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2013 Apr:27(4):509-13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04323.x. Epub 2011 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 22040510]

Monteagudo-Sánchez B, Luiña-Méndez L, Mosquera-Fernández A. Dermoscopic Features of a Digital Myxoid Cyst. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2019 Jun:27(2):129-130 [PubMed PMID: 31351511]

Kilinc Karaarslan I, Acar A, Aytimur D, Akalin T, Ozdemir F. Dermoscopic features in fungal melanonychia. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2015 Apr:40(3):271-8. doi: 10.1111/ced.12552. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25511570]

Kim HJ, Kim TW, Park SM, Lee HJ, Kim GW, Kim HS, Kim BS, Kim MB, Ko HC. Clinical and Dermoscopic Features of Fungal Melanonychia: Differentiating from Subungual Melanoma. Annals of dermatology. 2020 Dec:32(6):460-465. doi: 10.5021/ad.2020.32.6.460. Epub 2020 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 33911788]

Nagar R, Nayak CS, Deshpande S, Gadkari RP, Shastri J. Subungual hyperkeratosis nail biopsy: a better diagnostic tool for onychomycosis. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2012 Sep-Oct:78(5):620-4. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.100579. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22960819]

Subhadarshani S, Sarangi J, Verma KK. Dermoscopy of Subungual Wart. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2019 Jan:9(1):22-23. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0901a06. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30775143]

Yorulmaz A, Artuz F. A study of dermoscopic features of nail psoriasis. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. 2017 Feb:34(1):28-35. doi: 10.5114/ada.2017.65618. Epub 2017 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 28286468]

Yadav TA, Khopkar US. Dermoscopy to Detect Signs of Subclinical Nail Involvement in Chronic Plaque Psoriasis: A Study of 68 Patients. Indian journal of dermatology. 2015 May-Jun:60(3):272-5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.156377. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26120154]

Farias DC, Tosti A, Chiacchio ND, Hirata SH. [Dermoscopy in nail psoriasis]. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2010 Jan-Feb:85(1):101-3 [PubMed PMID: 20464097]

Ribeiro CF, Siqueira EB, Holler AP, Fabrício L, Skare TL. Periungual capillaroscopy in psoriasis. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2012 Jul-Aug:87(4):550-3 [PubMed PMID: 22892767]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOhtsuka T, Yamakage A, Miyachi Y. Statistical definition of nailfold capillary pattern in patients with psoriasis. International journal of dermatology. 1994 Nov:33(11):779-82 [PubMed PMID: 7822081]

Rajaei A, Dehghan P, Amiri A. Nailfold capillaroscopy in 430 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Caspian journal of internal medicine. 2017 Fall:8(4):269-274. doi: 10.22088/cjim.8.4.269. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29201317]

Altomonte L, Zoli A, Galossi A, Mirone L, Tulli A, Martone FR, Morini P, Laraia P, Magarò M. Microvascular capillaroscopic abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 1995 Jan-Feb:13(1):83-6 [PubMed PMID: 7774109]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakamura R, Broce AA, Palencia DP, Ortiz NI, Leverone A. Dermatoscopy of nail lichen planus. International journal of dermatology. 2013 Jun:52(6):684-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05283.x. Epub 2013 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 23432149]

Friedman P, Sabban EC, Marcucci C, Peralta R, Cabo H. Dermoscopic findings in different clinical variants of lichen planus. Is dermoscopy useful? Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2015 Oct:5(4):51-5. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0504a13. Epub 2015 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 26693092]

Nakamura RC, Costa MC. Dermatoscopic findings in the most frequent onychopathies: descriptive analysis of 500 cases. International journal of dermatology. 2012 Apr:51(4):483-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04720.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22435443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcGill NW, Gow PJ. Nailfold capillaroscopy: a blinded study of its discriminatory value in scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Australian and New Zealand journal of medicine. 1986 Aug:16(4):457-60 [PubMed PMID: 3467690]

Cutolo M, Sulli A, Pizzorni C, Accardo S. Nailfold videocapillaroscopy assessment of microvascular damage in systemic sclerosis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2000 Jan:27(1):155-60 [PubMed PMID: 10648032]

Herrick AL, Cutolo M. Clinical implications from capillaroscopic analysis in patients with Raynaud's phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010 Sep:62(9):2595-604. doi: 10.1002/art.27543. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20506306]

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, Nahir MA, Balbir-Gurman A. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Archives of dermatology. 2003 Aug:139(8):1027-30 [PubMed PMID: 12925391]

Tani C, Carli L, Vagnani S, Talarico R, Baldini C, Mosca M, Bombardieri S. The diagnosis and classification of mixed connective tissue disease. Journal of autoimmunity. 2014 Feb-Mar:48-49():46-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.008. Epub 2014 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 24461387]

Statham BN, Rowell NR. Quantification of the nail fold capillary abnormalities in systemic sclerosis and Raynaud's syndrome. Acta dermato-venereologica. 1986:66(2):139-43 [PubMed PMID: 2424237]

Shenavandeh S, Zarei Nezhad M. Association of nailfold capillary changes with disease activity, clinical and laboratory findings in patients with dermatomyositis. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2015:29():233 [PubMed PMID: 26793626]

Lee P, Leung FY, Alderdice C, Armstrong SK. Nailfold capillary microscopy in the connective tissue diseases: a semiquantitative assessment. The Journal of rheumatology. 1983 Dec:10(6):930-8 [PubMed PMID: 6663597]

Manfredi A, Sebastiani M, Cassone G, Pipitone N, Giuggioli D, Colaci M, Salvarani C, Ferri C. Nailfold capillaroscopic changes in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Clinical rheumatology. 2015 Feb:34(2):279-84. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2795-8. Epub 2014 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 25318613]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTosti A, Schneider SL, Ramirez-Quizon MN, Zaiac M, Miteva M. Clinical, dermoscopic, and pathologic features of onychopapilloma: A review of 47 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Mar:74(3):521-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.053. Epub 2015 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 26518173]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuarte AF, Correia O, Barreiros H, Haneke E. Giant subungual glomus tumor: clinical, dermoscopy, imagiologic and surgery details. Dermatology online journal. 2016 Oct 15:22(10):. pii: 13030/qt66f7b8wt. Epub 2016 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 28329592]

Mutsaers ER, Genders R, van Es N, Kukutsch N. Dermoscopy of glomus tumor: More white than pink. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Jul:75(1):e17-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.049. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27317535]

Kallis P, Miteva M, Patel T, Zaiac M, Tosti A. Onychomatricoma with Concomitant Subungual Glomus Tumor. Skin appendage disorders. 2015 Mar:1(1):14-7. doi: 10.1159/000371582. Epub 2015 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 27172169]

Ekin A, Ozkan M, Kabaklioglu T. Subungual glomus tumours: a different approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1997 Apr:22(2):228-9 [PubMed PMID: 9149994]

Thatte SS, Chikhalkar SB, Khopkar US. "Pink glow": A new sign for the diagnosis of glomus tumor on ultraviolet light dermoscopy. Indian dermatology online journal. 2015 Dec:6(Suppl 1):S21-3. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.171041. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26904443]

Lesort C, Debarbieux S, Duru G, Dalle S, Poulhalon N, Thomas L. Dermoscopic Features of Onychomatricoma: A Study of 34 Cases. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2015:231(2):177-83. doi: 10.1159/000431315. Epub 2015 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 26111574]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGinoux E, Perier Muzet M, Poulalhon N, Debarbieux S, Dalle S, Thomas L. Intraoperative dermoscopic features of onychomatricoma: a review of 10 cases. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2017 Jun:42(4):395-399. doi: 10.1111/ced.13077. Epub 2017 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 28244123]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJha AK, Sonthalia S, Khopkar U. Dermoscopy of Pyogenic Granuloma. Indian dermatology online journal. 2017 Nov-Dec:8(6):523-524. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_389_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29204415]

Zaballos P, Rodero J, Serrano P, Cuellar F, Guionnet N, Vives JM. Pyogenic granuloma clinically and dermoscopically mimicking pigmented melanoma. Dermatology online journal. 2009 Oct 15:15(10):10 [PubMed PMID: 19951628]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaddy AJ, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features of onychotillomania: A study of 36 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Oct:79(4):702-705. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.015. Epub 2018 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 29660424]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHalteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: Diagnosis and Management. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2017 Dec:18(6):763-770. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0289-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28488241]

Ning AY, Levoska MA, Zheng DX, Carroll BT, Wong CY. Treatment Options and Outcomes for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Nail Unit: A Systematic Review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Mar 1:48(3):267-273. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003319. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34889218]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence