Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Elbow Annular Ligament

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Elbow Annular Ligament

Introduction

The annular ligament is located within the elbow joint. The elbow joint is comprised of three bones that form three articulations which are all contained within the elbow joint capsule. The humerus, radius, and ulna interact in a complex, dynamic relationship to constitute three distinct joint articulations:[1]

- Ulnohumeral articulation

- Distal humerus (trochlea) and the proximal ulna (trochlear notch, or greater sigmoid notch)

- Radiocapitellar articulation

- Distal humerus (capitellum) and the proximal radius (radial head)

- Proximal radioulnar articulation

- The proximal ulna (radial notch, or lesser sigmoid notch) and the proximal radius (radial head)

The elbow joint is both a uniaxial, hinge joint (ulnohumeral articulation) and a pivot joint (radiocapitellar articulation). The ligaments surrounding the elbow joint connect one bone to another and provide static stability while allowing the motion to occur. The annular ligament is a critical component of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) complex. While the major roles of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and the LCL complex include primary support against excessive valgus stress and varus stress, respectively, the annular ligament plays an additionally important role as a primary stabilizing structure for the radial head articulation with the radial notch of the proximal ulna during forearm supination and pronation.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The annular ligament is a strong fibro-osseous circular structure that has attachments to the anterior and posterior margins of the radial notch (lesser sigmoid cavity) of the ulna. The annular ligament forms about four-fifths of a circle. The ligament subdivides into three layers:[2]

- Deep capsular structure

- Intermediate layer (annular ligament proper)

- Superficial structure

The annular ligament proper is composed of a superior oblique band and an inferior oblique.[3] Superiorly, the annular ligament is at its widest diameter and is continuous with the fibrous capsule of the elbow joint. Inferiorly, the ligament tapers as it surrounds the head and neck of the radius demonstrating distinct attachment sites to the radial neck via a synovial membrane; this allows the radius to freely rotate during forearm pronation and supination while preventing distal displacement. The anterior portion and posterior portions of the annular ligament become maximally taut when the forearm is in terminal supination and pronation, respectively.[4]

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) complex of the Elbow

Four ligaments form the LCL complex of the elbow. These ligaments include the annular ligament, accessory collateral ligament, lateral ulnar collateral ligament, and the radial collateral ligament. The LCL complex originates on the lateral humeral epicondyle.[5]

While the annular ligament plays a static stabilizing role against excessive varus stress at the elbow, the annular ligament's primary stabilizing role functions at the proximal radioulnar articulation. The annular ligament stabilizes the radial head within the radial notch of the ulna as it rotates during supination and pronation of the forearm.

The proximal, central, and distal band of the interosseous membrane also assists in proximal radial head stabilization. Under transverse displacement, the annular ligament along with the central and proximal band of the interosseous membrane equally contribute to stabilizing the radius. However, during forearm pronation and supination, the central band of the interosseous membrane contributes more to the stabilization of the radial head than the annular ligament and proximal band.[6]

Embryology

The annular ligament is a musculoskeletal structure and like the other ligaments throughout the body is derived from mesenchymal cells. The synovial membrane lining the space between the radial head and the annular ligament is also derived from mesenchymal cells. The annular ligament develops as a densification of the elbow joint capsule and becomes defined by week 12.[7] By week 22 the annular ligament is well developed.[8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the elbow joint derives from peri-articular anastomoses. Collateral and recurrent arterial branches from the brachial, deep brachial, ulnar, and radial arteries anastomose to provide consistent blood flow. The superior collateral branches include the radial collateral artery, superior ulnar collateral artery, and inferior ulnar collateral artery. The inferior collateral branches include the anterior ulnar recurrent artery, posterior ulnar recurrent artery, the radial recurrent artery, and the recurrent interosseous artery. The radial, ulnar, basilic, and brachial veins provide the elbow joint's venous outflow system.[9]

There are two different sets of lymph nodes at the elbow, the superficial and deep cubital nodes. They are above the medial epicondyle. The superficial cubital nodes drain the medial side of the hand and the forearm. The deep cubital nodes drain the elbow joint itself. The efferent vessels travel more proximal and drain into the axillary lymph nodes before entering the thoracic duct on the left side and the right lymphatic duct on the right side.

Nerves

Anteriorly, the elbow joint is innervated by branches of the median, radial, and musculocutaneous nerves. Posteriorly, the elbow joint receives innervation by branches of the ulnar nerve. The anterolateral aspect of the elbow capsule is innervated by branches of the radial nerve which is where the annular ligament is located.[10]

Muscles

The muscles crossing the elbow joint are subdivided into the flexors and extensors.

The primary elbow flexors include the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles. The biceps brachii is the largest of the flexors, and its primary function is as a primary and powerful forearm supinator.[11] The brachialis originates off the anterior humerus and inserts at the tuberosity of the ulna.[12] Additional elbow flexion occurs via the brachioradialis and pronator teres muscles. The brachioradialis originates from the lateral supracondylar humerus and attaches at the lateral aspect of the distal radius and assists in elbow flexion.[13] The pronator teres originates off the medial epicondyle of the distal humerus, as well as the coronoid, before inserting on the mid-lateral radial shaft. These attachments allow the pronator teres to assist in elbow flexion and forearm pronation.[14]

The extensors include the triceps brachii and anconeus. The triceps brachii is the largest extensor of the elbow and stabilizes the joint when the hand undergoes fine motor movements.[15] The anconeus is a small muscle that assists in elbow extension as well.[16]

Physiologic Variants

The annular ligament can demonstrate significant anatomic variation in its overall morphology. Multiple MRI-based studies and cadaveric dissection reports demonstrate the annular ligament appearing as a bi-lobed structure. Other studies demonstrate a morphologically broad annular ligamentous structure spanning superior to inferiorly at its attachment sites. In the instances that the ligament is bilobed, the anterior component remains its own separate, single band, while the posterior component demonstrates a fenestrated morphology. The latter can be seen as its own superior and inferior subdivisions, creating a funnel-shaped appearance.[17]

There are many variants of the synovial fold of the annular ligament. Not all people have a synovial fold. The synovial fold is its own distinct structure attached to the proximal end of the annular ligament, extending into the radiocapitellar joint capsule and blending with the common extensor tendon; this forms a single enthesis at the lateral epicondyle. The synovial fold can appear “meniscus-like” but is not a true meniscus. This fold can vary in thickness and can be an underlying cause of chronic, recalcitrant elbow pain syndromes.[18]

Surgical Considerations

Although many injuries involving the annular ligament can be managed conservatively with physical therapy, activity modifications, bracing, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), there are many indications for surgical intervention.

Radial head instability

Healthcare providers must recognize that, in general, isolated radial head instability is extremely uncommon.[19] In effect, this finding is almost always seen as a long-standing congenital condition or in association with additional forearm trauma (i.e., Monteggia fracture patterns). The latter is extremely important to recognize clinically, as management is nearly always observation alone.[20]

Patients with congenital radial head dislocations will present with a separate chief complaint, and the dislocation may be discovered incidentally. These patients may be asymptomatic, and the following factors support congenital dislocation over an acute, traumatic dislocation:[8][21]

- Bilateral radial head dislocations

- Hypoplastic capitellum and convex radial head

- Other congenital abnormalities

- No history of trauma

- Inability to reduce

There have been case reports of a portion of the annular ligament band interposing between the humeroradial interface as the band slips over the radial head during elbow flexion and extension. This "snapping" or "locking" can be thought of as analogous to a bucket handle tear of the meniscus in the knee. Patients are managed based on the severity of symptoms and the degree of disability that is attributable to these mechanical symptoms. Persistent mechanical symptoms may warrant surgery to remove the interposed fragment.[22]

Annular ligament reconstruction techniques

The annular ligament is typically reconstructed using any of the following techniques.

- Bell-Tawse technique[23][24][24]

- Utilizes the central portion of the triceps tendon to create a strip of tissue to pass around the radial neck and through a single drill hole in the ulna

- Modifications of the original technique have included either an additional ulnar shortening osteotomy or in using the lateral portion of the triceps tendon with a transcapitellar pin for stability

- Two-hole technique[25]

- Seel and Peterson drilled two holes in the proximal ulna at the original sites of the normal attachment of the annular ligament

- A third technique was described utilizing small bone staples and bone-anchoring devices as an alternative to transosseous drill holes[19]

Rehabilitation protocols depend on the specific surgical technique used for the reconstruction and follow surgeon preference. General rehabilitation phases include early range of motion to mitigate the risks of postoperative stiffness. Patients should return to full range-of-motion by 6 weeks after surgery. Strengthening exercises begin at about 8 to 12 weeks postop. Most patients can return to normal activities by six months to one year. Overhead athletes may take over a year to return to sport.

Clinical Significance

An annular ligament injury is much more common in children due to the skeletal immaturity of the elbow joint during development. Three common injuries associated with the annular ligament are radial head or neck fractures, nursemaid elbow dislocations, and Monteggia fracture patterns.[26]

A radial head or neck fracture occurs during a fall on an outstretched hand or trauma/falls with the elbow in extension and forearm in pronation. Because the annular ligament wraps around the head of the radius, a fracture in this area can lead to damage to the ligament, and could potentially compromise joint stability as a sequela of the original injury.[27]

In pediatric patients, a radial head subluxation, also known as a nursemaid elbow or a pulled elbow, occurs due to a sudden pull on an extended arm, often when a parent lifts a child by the wrist or a fall.[28] This injury occurs almost entirely in the pediatric population since the annular ligament has increased laxity in children compared to adults. The average age is 1-4 years old and girls are more susceptible than boys. Children above the 75th percentile for weight are more frequently affected by this condition.[29] The classic symptoms of a radial head subluxation in pediatric patients consists of a history of the child refusing to use the arm. The child may hold the extremity with the elbow in extension with the forearm pronated or slightly flexed with the forearm pronated. On exam, there is typically pain localized to the dorsal aspect of the proximal forearm with typically no swelling.[30] Often there may only be subtle decreases in flexion and extension range of motion, but supination is significantly limited. The annular ligament is frequently interposed between the radial head and the capitellum of the humerus. X-ray of the elbow is usually unnecessary since the diagnosis can be made clinically, although after two failed attempts to reduce the dislocation imaging should be considered.[30] Treatment includes closed reduction using either hyperpronation or a combination of flexion and supination maneuvers. The prognosis in these patients is typically excellent in the long-term.[31]

Monteggia fracture-dislocations are relatively rare injuries in the pediatric population. Although forearm fractures are the most common fracture in the pediatric population, Monteggia fracture-dislocations constitute only about 1% of all pediatric forearm fractures.[32][33][32] These injuries have a proximal one-third of the ulna (olecranon) fracture with an associated radial head dislocation from the annular ligament. Mechanisms of injury include a fall on an outstretched hand with excessive forearm pronation and less commonly, direct trauma on the dorsal surface of the proximal forearm. These injuries commonly require surgical intervention given the high incidence of long-term elbow dysfunction following either missed injury or following suboptimal clinical management.[34] Surgical management consists of open reduction internal fixation of the proximal ulna. Upon restoration of ulnar length and stability, the radial head can be reduced with a restoration of the anatomic relationship between the radial head, capitellum, and the annular ligament.[35]

The prognosis in children with Monteggia fractures is usually good with early intervention and treatment. However, several studies in the literature have focused on the long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes following surgical management of pediatric patients with delayed/missed diagnosis of Monteggia fracture-dislocations. The most commonly performed procedure includes an open reduction with ulnar osteotomy with or without annular ligament reconstruction.[36]Nakamura et al. reported good long-term outcomes when performing open reduction if the patient is less than twelve years of age or within three years after the initial injury.[37]

Media

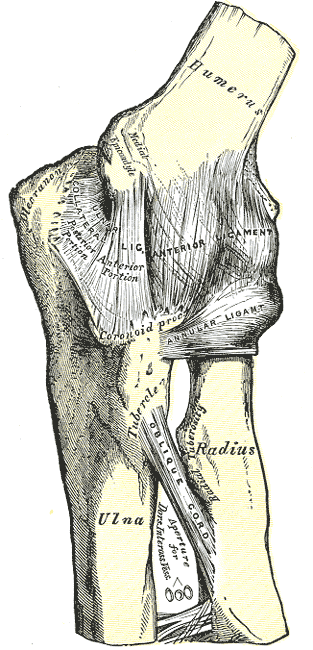

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Left Elbow Joint, Anterior and Internal Ligaments. The illustration shows the left elbow joint and the anterior and internal ligaments.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Alcid JG, Ahmad CS, Lee TQ. Elbow anatomy and structural biomechanics. Clinics in sports medicine. 2004 Oct:23(4):503-17, vii [PubMed PMID: 15474218]

Barnes JW, Chouhan VL, Egekeze NC, Rinaldi CE, Cil A. The annular ligament-revisited. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2018 Jan:27(1):e16-e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.07.031. Epub 2017 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 28993111]

Bozkurt M, Acar HI, Apaydin N, Leblebicioglu G, Elhan A, Tekdemir I, Tonuk E. The annular ligament: an anatomical study. The American journal of sports medicine. 2005 Jan:33(1):114-8 [PubMed PMID: 15611007]

Mak S, Beltran LS, Bencardino J, Orr J, Jazrawi L, Cerezal L, Beltran J. MRI of the annular ligament of the elbow: review of anatomic considerations and pathologic findings in patients with posterolateral elbow instability. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2014 Dec:203(6):1272-9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12263. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25415705]

Bryce CD, Armstrong AD. Anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2008 Apr:39(2):141-54, v. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2007.12.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18374805]

Anderson A, Werner FW, Tucci ER, Harley BJ. Role of the interosseous membrane and annular ligament in stabilizing the proximal radial head. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2015 Dec:24(12):1926-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.030. Epub 2015 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 26190665]

Mérida-Velasco JA, Sánchez-Montesinos I, Espín-Ferra J, Mérida-Velasco JR, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Jiménez-Collado J. Development of the human elbow joint. The Anatomical record. 2000 Feb 1:258(2):166-75 [PubMed PMID: 10645964]

Al-Qattan MM, Abou Al-Shaar H, Alkattan WM. The pathogenesis of congenital radial head dislocation/subluxation. Gene. 2016 Jul 15:586(1):69-76. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.04.002. Epub 2016 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 27050104]

Wavreille G, Dos Remedios C, Chantelot C, Limousin M, Fontaine C. Anatomic bases of vascularized elbow joint harvesting to achieve vascularized allograft. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2006 Oct:28(5):498-510 [PubMed PMID: 16838085]

Nourbakhsh A, Hirschfeld AG, Schlatterer DR, Kane SM, Lourie GM. Innervation of the Elbow Joint: A Cadaveric Study. The Journal of hand surgery. 2016 Jan:41(1):85-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.10.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26710740]

Tiwana MS, Charlick M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Biceps Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137823]

Plantz MA, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachialis Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31869094]

Lung BE, Ekblad J, Bisogno M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Brachioradialis Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252366]

Dididze M, Tafti D, Sherman AL. Pronator Teres Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252346]

Landin D, Thompson M, Jackson M. Functions of the Triceps Brachii in Humans: A Review. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2018 Apr:10(4):290-293. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3340w. Epub 2018 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 29511416]

Gangatharam S. Anconeus syndrome: A potential cause for lateral elbow pain and its therapeutic management-A case report. Journal of hand therapy : official journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists. 2021 Jan-Mar:34(1):131-134. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2019.04.002. Epub 2019 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 31492479]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSanal HT, Chen L, Haghighi P, Trudell DJ, Resnick DL. Annular ligament of the elbow: MR arthrography appearance with anatomic and histologic correlation. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2009 Aug:193(2):W122-6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1887. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19620413]

Duparc F, Putz R, Michot C, Muller JM, Fréger P. The synovial fold of the humeroradial joint: anatomical and histological features, and clinical relevance in lateral epicondylalgia of the elbow. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2002 Dec:24(5):302-7 [PubMed PMID: 12497221]

Tan L, Li YH, Sun DH, Zhu D, Ning SY. Modified technique for correction of isolated radial head dislocation without apparent ulnar bowing: a retrospective case study. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2015:8(10):18197-202 [PubMed PMID: 26770420]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHayami N, Omokawa S, Iida A, Kira T, Moritomo H, Mahakkanukrauh P, Kraisarin J, Shimizu T, Kawamura K, Tanaka Y. Effect of soft tissue injury and ulnar angulation on radial head instability in a Bado type I Monteggia fracture model. Medicine. 2019 Nov:98(44):e17728. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017728. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31689815]

Sachar K, Mih AD. Congenital radial head dislocations. Hand clinics. 1998 Feb:14(1):39-47 [PubMed PMID: 9526155]

Kerver N, Boeddha AV, Gerritsma-Bleeker CLE, Eygendaal D. Snapping of the annular ligament: a uncommon injury characterised by snapping or locking of the elbow with good surgical outcomes. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2019 Jan:27(1):326-333. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5076-2. Epub 2018 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 30073382]

Cappellino A, Wolfe SW, Marsh JS. Use of a modified Bell Tawse procedure for chronic acquired dislocation of the radial head. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 1998 May-Jun:18(3):410-4 [PubMed PMID: 9600573]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCanton G, Hoxhaj B, Fattori R, Murena L. Annular ligament reconstruction in chronic Monteggia fracture-dislocations in the adult population: indications and surgical technique. Musculoskeletal surgery. 2018 Oct:102(Suppl 1):93-102. doi: 10.1007/s12306-018-0564-6. Epub 2018 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 30343474]

Seel MJ, Peterson HA. Management of chronic posttraumatic radial head dislocation in children. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 1999 May-Jun:19(3):306-12 [PubMed PMID: 10344312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCrowther M. Elbow pain in pediatrics. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2009 Jun:2(2):83-7. doi: 10.1007/s12178-009-9049-4. Epub 2009 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 19468873]

Burkhart KJ, Wegmann K, Müller LP, Gohlke FE. Fractures of the Radial Head. Hand clinics. 2015 Nov:31(4):533-46. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2015.06.003. Epub 2015 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 26498543]

Welch R, Chounthirath T, Smith GA. Radial Head Subluxation Among Young Children in the United States Associated With Consumer Products and Recreational Activities. Clinical pediatrics. 2017 Jul:56(8):707-715. doi: 10.1177/0009922816672451. Epub 2016 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 28589762]

Vitello S, Dvorkin R, Sattler S, Levy D, Ung L. Epidemiology of nursemaid's elbow. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Jul:15(4):554-7. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.1.20813. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25035767]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYamanaka S, Goldman RD. Pulled elbow in children. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2018 Jun:64(6):439-441 [PubMed PMID: 29898933]

Bexkens R, Washburn FJ, Eygendaal D, van den Bekerom MP, Oh LS. Effectiveness of reduction maneuvers in the treatment of nursemaid's elbow: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Jan:35(1):159-163. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.059. Epub 2016 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 27836316]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNaranje SM, Erali RA, Warner WC Jr, Sawyer JR, Kelly DM. Epidemiology of Pediatric Fractures Presenting to Emergency Departments in the United States. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2016 Jun:36(4):e45-8. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000595. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26177059]

Beutel BG. Monteggia fractures in pediatric and adult populations. Orthopedics. 2012 Feb:35(2):138-44. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120123-32. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22300997]

Hubbard J, Chauhan A, Fitzgerald R, Abrams R, Mubarak S, Sangimino M. Missed Pediatric Monteggia Fractures. JBJS reviews. 2018 Jun:6(6):e2. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00116. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29870420]

Leonidou A, Pagkalos J, Lepetsos P, Antonis K, Flieger I, Tsiridis E, Leonidou O. Pediatric Monteggia fractures: a single-center study of the management of 40 patients. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2012 Jun:32(4):352-6. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31825611fc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22584834]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoyal T, Arora SS, Banerjee S, Kandwal P. Neglected Monteggia fracture dislocations in children: a systematic review. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2015 May:24(3):191-9. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000147. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25714935]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNakamura K, Hirachi K, Uchiyama S, Takahara M, Minami A, Imaeda T, Kato H. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes after open reduction for missed Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2009 Jun:91(6):1394-404. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00644. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19487517]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence