Introduction

The gag reflex, also known as the pharyngeal reflex, is an involuntary reflex involving bilateral pharyngeal muscle contraction and elevation of the soft palate (see Figure. Gag Reflex). This reflex may be evoked by stimulation of the posterior pharyngeal wall, tonsillar area, or tongue base. The gag reflex is believed to be an evolutionary reflex that developed as a method to prevent swallowing foreign objects and prevent choking. It is essential to evaluate the medullary brainstem, as it plays a role in declaring brain death.[1]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

In certain instances, a lack of a gag reflex may be a symptom of a more severe medical condition, such as cranial nerve damage or brain death. Contrast this with a hypersensitive gag reflex (HGR), which may be caused by anxiety, postnatal drip, acid reflux, or oral stimulation, such as during dental treatments.

Development

The gag reflex is mediated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) and the vagus nerve (CN X). Embryologically, the glossopharyngeal nerve is associated with the derivatives of the third pharyngeal arch, while the vagus nerve is associated with the derivatives of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches.[2]

Function

The gag reflex is a natural somatic response in which the body attempts to eliminate unwanted agents or foreign objects from the oral cavity through muscle contraction at the base of the tongue and the pharyngeal wall.[3] In the first few months of life, the gag reflex is triggered by any food that the nucleus tractus solitarius (a brain stem region) deems too large or solid for a baby to digest. Starting around 67 or 7 months of age, the gag reflex diminishes, allowing infants to swallow more solid foods.[4]

Mechanism

The gag reflex can be classified as either somatogenic or psychogenic. A somatogenic gag reflex follows direct physical contact with a trigger area, which may include the base of the tongue, posterior pharyngeal wall, or tonsillar area. A psychogenic gag reflex presents following a mental trigger, typically without direct physical contact. In cases of psychogenic gag reflexes, even the thought of touching a sensitive trigger area, such as when going to the dentist, can induce gagging.[5] The gag reflex is controlled by both the glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus (CN X) nerves, which serve as the afferent (sensory) and the efferent (motor) limbs for the reflex arc, respectively. The nerve roots of cranial nerves IX and X exit the medulla through the jugular foramen and descend on either side of the pharynx to innervate the posterior pharynx, posterior one-third of the tongue, soft palate, and the stylopharyngeus muscle.[6]

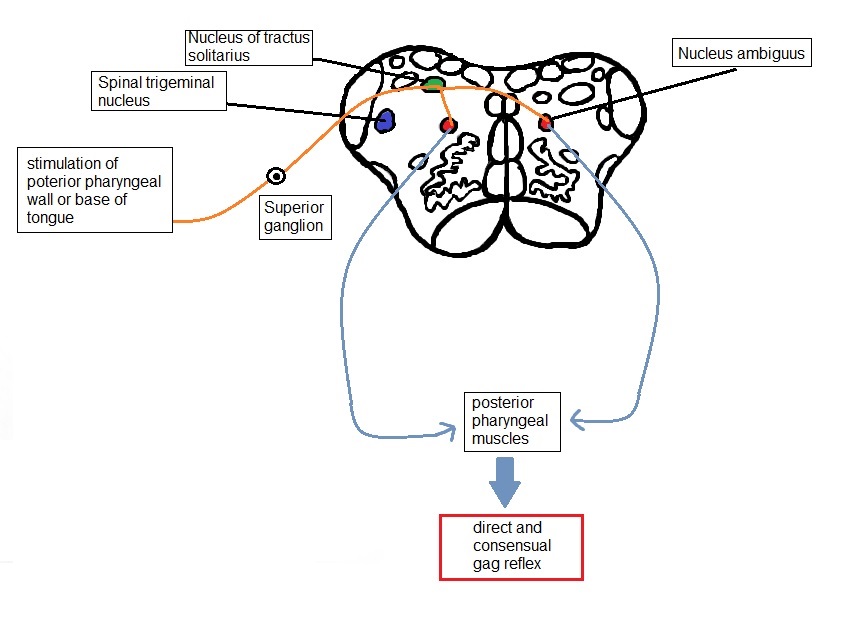

The stimulus is provided by sensation to the posterior pharyngeal wall, the tonsillar pillars, or the base of the tongue. These sensations are carried by CN IX, which acts as the afferent limb of the reflex to the ipsilateral nucleus solitarius (also referred to as the gustatory nucleus) after synapsing at the superior ganglion located in the jugular foramen. These nuclei send fibers to the nucleus ambiguus, a motor nucleus in the rostral medulla. Efferent nerve fibers to the pharyngeal musculature traverse from the nucleus ambiguus through CN X, resulting in the bilateral contraction of the posterior pharyngeal muscles. Contraction of the pharyngeal musculature ipsilateral to the side of the stimulus is known as the direct gag reflex, and contraction of the musculature on the contralateral side is known as the consensual gag reflex. Stimulation of the soft palate can also elicit the gag reflex; in this case, the sensory limb is the trigeminal nerve (CN V). Here, sensory stimulation of the soft palate travels through the nucleus of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve.

Related Testing

Equipment

The gag reflex can be elicited using a tongue blade or soft cotton applicator. However, a suction device may be most convenient for testing in an intubated patient.

Technique

The examiner stimulates the posterior pharynx using a tongue blade or cotton applicator. After doing so, the patient produces a gagging reaction, which may lead to vomiting in some individuals. Additionally, the elevation of the bilateral posterior pharyngeal muscles requires examination. In a study among 104 medical students assessing the gag reflex, researchers noticed that stimulation of the posterior pharynx was more likely to elicit a gag reflex than stimulation of the posterior tongue.[7] An asymmetric response or absence of response when stimulating 1 side indicates the presence of pathology and warrants further assessment. The soft palatal reflex can help assess the function of CN IX and CN X, as this reflex may be intact in the absence of the gag reflex. The voice is evaluated by looking for hoarseness and dysphonia to determine CN X pathology. Research has also found that the cough reflex was better reproduced in intubated patients than the gag reflex to test for brainstem function.[8] As various techniques are used to assess the gag reflex, there is poor inter-observer agreement. Hence, a standard method of examining patients for specific clinical scenarios is warranted. However, the gag reflex remains imperative in assessing brainstem function, especially in the setting of brain death.

Contraindications

During airway assessment for intubation in an obtunded patient, the gag reflex should not be performed due to the risk of vomiting and subsequent aspiration.[9] Assessing the oral cavity in patients with a hypersensitive gag reflex may be difficult. These patients may benefit from intravenous sedation during prosthodontic treatment.[10]

Pathophysiology

As previously stated, individuals may suffer from either a lack of a gag reflex or a hypersensitive gag reflex (HGR). It is not uncommon for an individual to lack a gag reflex. According to 1 study involving 140 people, 37% were found to have an absent gag reflex.[11] This percentage may be higher in patients with a history of smoking or tobacco use. However, clinical judgment is indicated. In certain instances, a lack of a gag reflex may be a symptom of a more severe medical condition, such as cranial nerve damage or brain death.

Testing the gag reflex can help assess CN IX and CN X damage. To test the gag reflex, gently touch 1 and then the other palatal arch with a cotton swab or tongue blade, waiting each time for gagging. If the glossopharyngeal (IX) nerve is damaged on 1 side, there is no response when touched. If the vagus (X) nerve is damaged and either side is touched, the soft palate elevates and moves toward the affected side. If CN IX and CN X are damaged on 1 side, touching the intact side results in a unilateral response with a deviation of the palate to that side. There is no response when touching the damaged side. Conversely, another study showed that 10% to 15% of individuals have a hypersensitive gag reflex.[12] Those with an HGR often gag while eating thick or sticky foods that tend to get stuck in the mouth, such as bananas and mashed potatoes.

Following intraoral stimulation, afferent fibers from the trigeminal (CN V), glossopharyngeal (CN IX), and vagus (CN X) nerves pass to the medulla oblongata. From here, efferent impulses give rise to spasmodic and uncoordinated muscle movements characteristic of gagging. The portion of the medulla oblongata that receives these afferent impulses is also close to the vomiting, salivary, and cardiac centers, which may be stimulated during gagging.[3] This explains why gagging may be accompanied by excessive salivation, lacrimation, sweating, fainting, or even a panic attack in a minority of patients. Furthermore, neural pathways from the gagging center to the cerebral cortex allow the reflex to be modified by higher centers, thus making it possible to initiate gagging by imagining a disagreeable experience or controlling the reflex to some extent by distractive action.[13]

Bulbar Palsy

Bulbar palsy is a set of signs and symptoms that present following damage to the lower cranial nerves: the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), vagus nerve (CN X), accessory nerve (CN XI), and hypoglossal nerve (CN XII). Bulbar palsy symptoms can include a lack of a gag reflex, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), excessive drooling, and slurred speech (dysarthria), most commonly caused by a brainstem stroke or tumor. Other causes of bulbar palsy include genetic (acute intermittent porphyria), degenerative (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), infective (Guillain-Barré syndrome, Lyme disease), toxic (botulism), and autoimmune (myasthenia gravis) causes.

Clinical Significance

The gag reflex once served as a method of detecting dysphagia in the setting of an acute stroke. In 1 study comparing gag reflex to bedside swallowing assessment in 242 patients, researchers found that the absence of a gag reflex was specific for and consistent with the inability to swallow as assessed at the bedside but not sensitive in stroke patients. This study showed that the specificity of the gag reflex in detecting dysphagia was 96%, with a sensitivity of 39%. However, an intact gag reflex indicates protection against long-term swallowing issues and predicts a decreased requirement for enteral feeding.[14]

Research has found that the posterior pharyngeal muscles, which control the gag reflex, are independent of the muscles responsible for swallowing. Therefore, clinicians should not rely upon an absent gag reflex as a predictor for aspiration in stroke patients. Indirect laryngoscopy is a better alternative to performing the gag reflex to assess airway safety. Researchers have also noted that 1 out of 3 people may lack a gag reflex through habituation or be influenced by emotions through higher centers. Pharyngeal sensation, in contrast, is rarely absent and is thus used as an alternative to gag reflex testing and could prove better at predicting future problems with swallowing.[14] Finally, performing the gag reflex is necessary when assessing brainstem function to determine brain death. Confirmation of brain death is done in part by absent brainstem reflexes, which include an absent gag reflex.[15]

Patients with a hypersensitive gag reflex may state that they have issues swallowing pills or larger pieces of food. Typically, these patients may also defer going to the dentist or practicing appropriate oral hygiene due to the presence of an HGR. Numerous studies have been performed to try and find ways to lessen the gag reflex of patients with HGR in the clinical or everyday setting. These studied interventions have included anti-nausea medications, herbal remedies, acupressure, acupuncture, behavioral therapies, and sedatives. Results indicate no evidence that the listed interventions are adequate for maintaining the gag reflex.[13] Further trials with different interventions are needed. As a clinician, you may encounter a patient suffering from an eating disorder involving forced vomiting or purging at some point in your career. These patients may use their fingers or another instrument (eg, spoon, pencil) to stimulate their gag reflex and expel gastric contents. Patients who regularly induce self-vomiting may have a diminished gag reflex due to desensitization caused by overstimulation.

Media

References

Park MJ, Byun JS, Jung JK, Choi JK. The correlation of gagging threshold with intra-oral tactile and psychometric profiles in healthy subjects: A pilot study. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2020 May:47(5):591-598. doi: 10.1111/joor.12940. Epub 2020 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 32003041]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrisdal A, Trainor PA. Development and evolution of the pharyngeal apparatus. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2014 Nov-Dec:3(6):403-18. doi: 10.1002/wdev.147. Epub 2014 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 25176500]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBassi GS, Humphris GM, Longman LP. The etiology and management of gagging: a review of the literature. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 2004 May:91(5):459-67 [PubMed PMID: 15153854]

Stevenson RD, Allaire JH. The development of normal feeding and swallowing. Pediatric clinics of North America. 1991 Dec:38(6):1439-53 [PubMed PMID: 1945550]

Saunders RM, Cameron J. Psychogenic gagging: identification and treatment recommendations. Compendium of continuing education in dentistry (Jamesburg, N.J. : 1995). 1997 May:18(5):430-3, 436, 438 passim [PubMed PMID: 9533356]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKlimaj Z, Klein JP, Szatmary G. Cranial Nerve Imaging and Pathology. Neurologic clinics. 2020 Feb:38(1):115-147. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.08.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31761055]

Lim KS, Hew YC, Lau HK, Lim TS, Tan CT. Bulbar signs in normal population. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2009 Jan:36(1):60-4 [PubMed PMID: 19294890]

Polverino M, Polverino F, Fasolino M, Andò F, Alfieri A, De Blasio F. Anatomy and neuro-pathophysiology of the cough reflex arc. Multidisciplinary respiratory medicine. 2012 Jun 18:7(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-5. Epub 2012 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 22958367]

Mackway-Jones K, Moulton C. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Gag reflex and intubation. Journal of accident & emergency medicine. 1999 Nov:16(6):444-5 [PubMed PMID: 10572821]

Yoshida H, Ayuse T, Ishizaka S, Ishitobi S, Nogami T, Oi K. Management of exaggerated gag reflex using intravenous sedation in prosthodontic treatment. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 2007 Aug:212(4):373-8 [PubMed PMID: 17660702]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDavies AE, Kidd D, Stone SP, MacMahon J. Pharyngeal sensation and gag reflex in healthy subjects. Lancet (London, England). 1995 Feb 25:345(8948):487-8 [PubMed PMID: 7861875]

Neumann JK, McCarty GA. Behavioral approaches to reduce hypersensitive gag response. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 2001 Mar:85(3):305 [PubMed PMID: 11264940]

Eachempati P, Kumbargere Nagraj S, Kiran Kumar Krishanappa S, George RP, Soe HHK, Karanth L. Management of gag reflex for patients undergoing dental treatment. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019 Nov 13:2019(11):. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011116.pub3. Epub 2019 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 31721146]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRamsey D, Smithard D, Donaldson N, Kalra L. Is the gag reflex useful in the management of swallowing problems in acute stroke? Dysphagia. 2005 Spring:20(2):105-7 [PubMed PMID: 16172818]

Goila AK, Pawar M. The diagnosis of brain death. Indian journal of critical care medicine : peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2009 Jan-Mar:13(1):7-11. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.53108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19881172]