Introduction

The bilobed flap is a local transposition flap used primarily for the reconstruction of small to moderate-sized cutaneous nasal defects, although it can be applied to other areas of the body. It was first described in 1918 by Esser for use in nasal tip reconstruction. The original flap used a rotational arc of 180 degrees and based the second lobe superiorly, towards the glabellar region.

In 1953, Zimany demonstrated that the second and third lobes could be smaller than the first and that the flap could be utilized for reconstruction in more anatomical areas. In the 1980s, McGregor and Soutar introduced the concept that a reduced pivotal angle would result in smaller standing cutaneous deformities and decreased pincushioning. Zitelli went on to describe limiting the total rotational arc to between 90 and 110 degrees; this variant is the most common modification in use today. This overview of the bilobed flap will focus on the most recent modification. Herein, the relevant anatomy and the situations in which the bilobed flap is most effectively employed will be described, as well as how to plan and transfer this versatile flap.[1][2][3][4][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The bilobed flap is a double transposition flap wherein the first lobe serves to fill the primary defect, and a second lobe fills the defect vacated by the first lobe (the "secondary defect"). This approach distributes tension across a wider area of tissue, but at the cost of additional incision length and scarring in a complex curvilinear pattern that makes concealment within aesthetic subunit boundaries challenging. The blood supply to bilobed flaps arises from the subdermal plexus; for this reason, most surgeons categorize bilobed flaps as having a "random pattern" blood supply, as opposed to an "axial" blood supply that comes from a named vessel entering the flap. Most bilobed flaps are therefore raised in a subdermal plane, ensuring that the subdermal vascular plexus remains intact, although many surgeons will raise nasal bilobe flaps in a submuscular plane to include the nasalis muscle in the flap and improve perfusion. Venous drainage flows through the subdermal plexus as well, but is sometimes less reliable than the arterial inflow, making flap congestion, at least over the first week postoperatively, fairly common. Lymphatic drainage can be problematic as well, and the dependent part of the flap will often swell such that its skin surface rises above that of the surrounding tissue - a phenomenon known as a "trapdoor deformity."[5][6][7]

Indications

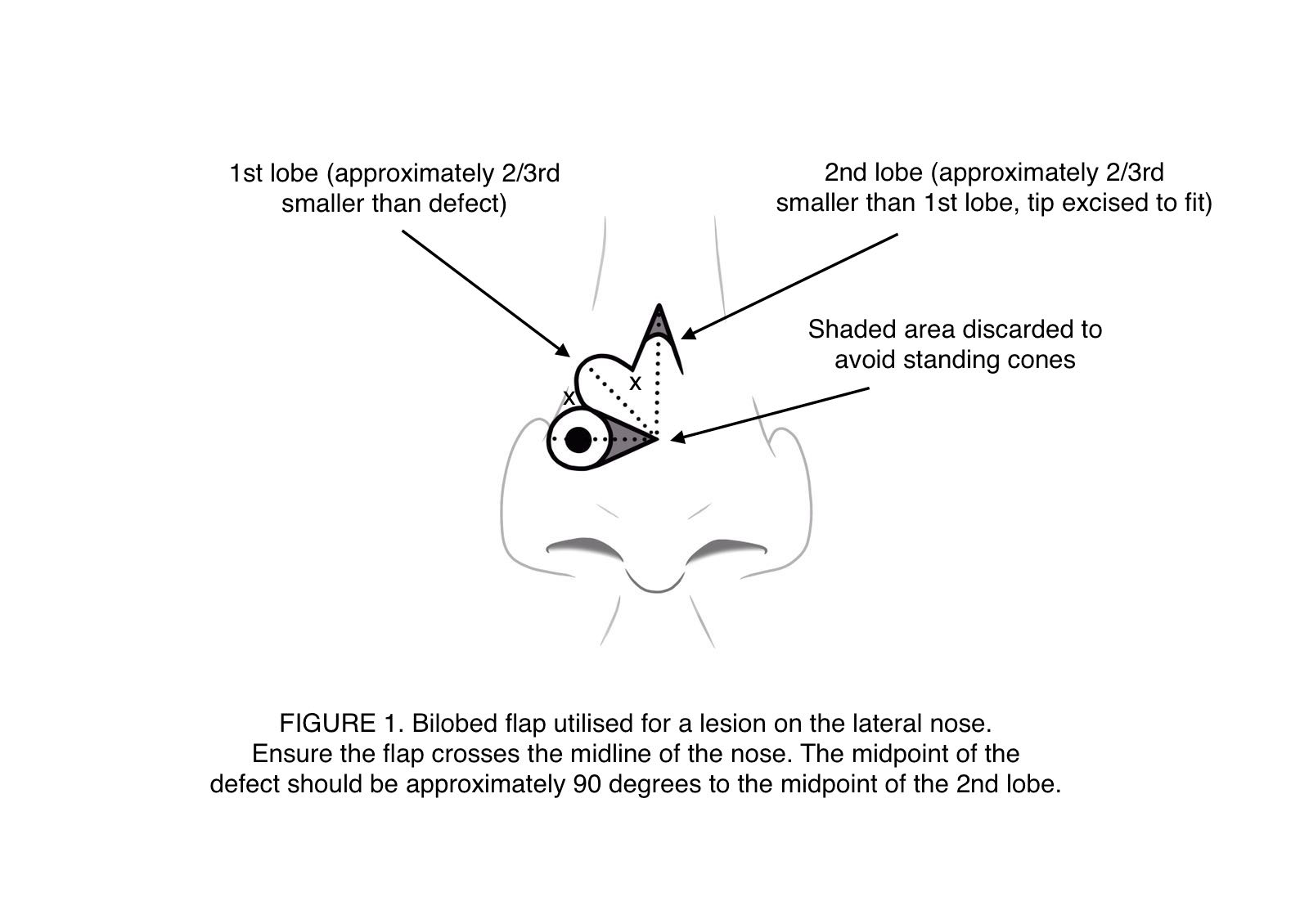

The bilobed flap was first described for its application to reconstruction of the nasal tip using a rotational arc of 180 degrees and having the secondary donor site in the glabellar region. This technique has fallen out of favor as the large arc created large flaps that require significant undermining. The bilobed flap is now more commonly used for reconstruction of the lateral portion of the nose. It utilizes the mobile skin of the cephalic part of the nose to replace the more immobile skin in the caudal part of the nose. The second donor site should remain located superiorly, towards the glabella, which permits at least one segment of the scar to hide in the nasofacial junction (see image).

The bilobed flap is very versatile, and although frequently associated with nasal reconstruction, it is, in fact, applicable in many anatomical locations. Tissiani et al. describe the versatility of the bilobed flap in a case series of 42 patients who had bilobed flaps tranposed in a wide range of anatomical sites including, but not limited to, cheek, upper lip, zygoma, upper limb, and lower limb.[8][9][10]

Contraindications

Contraindications for bilobed flap transposition include any conditions that will substantially decrease soft tissue viability in the area in question. Patients wtih peripheral vascular disease near the wound, or patients who smoke, may not be ideal candidates for flap surgery. The anticoagulated patient may also present an intraoperative and/or postoperative challenge due to excessive bleeding and the risk of hematoma formation, which can kill a flap. Lastly, patients with localized injury to the tissue that would be transposed, such as scarring, history of radiation, or active infection/inflammation, should consider other reconstructive options.

Additionally, any comorbidities that make the risk of anesthesia unacceptably high must be considered contraindications for bilobed flap transposition. These condititions include but are not limited to: severe cardiopulmonary disease, history of malignant hyperthermia, and history of allergic reactions to local anesthetics. Patients with these diagnoses should undergo preoperative medical clearance with a primary care provider.

Equipment

Preoperative

- Skin marker

- 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in 3 cc syringes with 30 gauge, 0.5 inch needles

- Isopropanol, chlorhexidine gluconate, or povidone iodine for skin cleansing

Intraoperatively

- #15 blade, #15C blade, or #6700 beaver blade

- Adson-Brown and 0.5 mm Castroviejo forceps

- Kaye blepharoplasty scissors

- Suture scissors

- Bipolar electrocautery

- Guthrie skin hooks

- Castroviejo needle driver

- Absorbable (such as poligelcaprone or polyglactin) and non-absorbable (such as nylon or polypropylene) suture

Postoperatively

- Bacitracin ointment, or:

- Skin glue, or:

- Adhesive and sterile tape strips

Personnel

These procedures are not particularly personnel-intensive in most cases. If performed under local anesthesia, they can take place in an outpatient clinic setting, with the surgeon and a nurse and/or a scrub assistant. In the main operating room, which may be required for larger reconstructions, particularly if the lesion is a large malignant tumor and is excised in the same session, more personnel are required. In addition to a surgeon, an anesthesia provider, a circulating nurse, a scrub tech, and a surgical first assist should be present.

Preparation

The preoperative discussion should include what to expect leading up to and during surgery, as well as what sort of aftercare for the flap will be required postoperatively. Postoperative medications, pain control, and wound care should also be discussed, and written instructions provided. Risks, benefits, alternatives, and indications to bilobed flap transposition should also be discussed, and an informed consent form should be signed at the time the surgical site is marked in the peroperative holding area. Specifically, the surgeon should educate the patient regarding the risks of pain, bleeding, infection, unfavorable scarring, cosmetic distortion of surrounding structures, and the possibility of flap nonviability, which may necessitate subsequent procedures. Risks of recurrent malignancy and of general anesthesia should also be discussed as necessary.

Technique or Treatment

The vast majority of these procedures will be performed under local anesthesia. Because infiltration of local anesthetic often results in distortion of lines of contour, the flap should be planned and marked prior to infiltration of local anesthetic.

This article will use the example of the side wall of the nose to illustrate planning the bilobed flap. When planning local flaps on the nose, it is advisable to avoid crossing the aesthetic boundary between the nose and the cheek. The second lobe of the flap should be positioned superiorly, pointing towards the glabellar region, in order to facilitate placement of the vertical portion of the scar in the nasofacial junction.

Firstly, the lesion due to be removed should be marked with an appropriate margin circumferentially. Nasal tip defects of 10-15 mm in diameter are ideally suited to bilobed flap reconstruction. Once the lesion has been excised, the wound bed should be removed down to the level of the perichondrium, not for oncological integrity, but for ease of dissection and maximization of flap perfusion. The first lobe of the flap is marked directly superior to the defect, with a diameter 80-100% of that of the defect. For nasal tip defects, the first lobe diameter usually needs to be quite close to the defect's diameter because the skin of the lower nasal dorsum and supratip is not particularly elastic. The second lobe of the flap is then drawn immediately adjacent to the first lobe, in the half past one o'clock position, 45 degrees off the vertical axis. This second lobe should then have a "hat" added to it: a vertical isoceles triangle with a 30 degree point that will facilitate closure without a standing cutaneous deformity. At this point, some surgeons will then excise a Burow's triangle extending laterally from the defect along the base of the flap, but others prefer to wait until they are certain exactly how much excess tissue needs to be excised (see video and figures).

After the incisions are made, wide undermining should be performed in a subdermal plane, or if on the nose, a submuscular plane. Undermining is critical in almost all local flap reconstructions, as it is not only the flap that moves to the wound, but the wound that moves to the flap as well. After achieving hemostasis, closure begins. The tertiary defect, where the "hat" was raised, should be sutured first, with buried, interrupted, deep dermal stitches. On the nasal dorsum, a 5-0 poliglecaprone suture works well. The secondary defect can then be closed, which usually requires excision of some or all of the "hat." Finally, the primary defect is closed and the Burow's triangle excised, if it hadn't been resected already, as mentioned above. Lastly, a superficial suture layer should be placed; on the nose, a 6-0 polypropylene is suitable, which can be removed after one week. Adhesive tape strips and a nasal cast may be applied as well, similar to a rhinoplasty dressing. This will help reduce edema and protect the surgical site.

Complications

The potential complications specific to this procedure are swelling, scarring, flap necrosis, infection, and bleeding. Due to the crescentic shape of the flap, it is at risk of developing a pincushion deformity as a result of subdermal tissue contraction. When tension at flap inset is minimized, less pincushioning is seen. Decreasing the arc of rotation is one way to minimize tension at closure, as is wide undermining. Standing cutaneous deformities are also a risk, and again can be reduced with a smaller rotation arc. In the original bilobed flap, as described by Esser with a 180 degree rotation, standing cutaneous deformities were almost inevitable, but they are much less common when employing the Zitelli modification. If closing tension is too great, perfusion will suffer, particularly venous drainge, and flap loss may occur. Infection can also appear in any area of the wound, but is more liable to appear in areas of necrosis. Postoperative bleeding can result in hematoma formation under the flap, which may compromise blood flow and potentially result in loss of the flap.

Clinical Significance

The bilobed flap is a versatile local transposition flap that spreads tension across a wider surface area than a conventional rotational flap, but sacrifices scar length and concealability in the process. It has undergone many technical improvements over the years, and is most commonly used for reconstruction in the head and neck region, particularly the nasal tip, but can be employed in other areas of the body as well.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bilobed flap transposition is a commonly employed reconstructive modality used by plastic surgeons, facial plastic surgeons, otolaryngologists, oral surgeons, and dermatologists. While most cases do not requires a large team, nursing care both during and after the procedure is essential to improve healing outcomes. Wound care nurses and physicians who have patients with facial and extremity defects that need closure should consult with a surgeon experienced in cutaneous reconstruction. [level 5]

Media

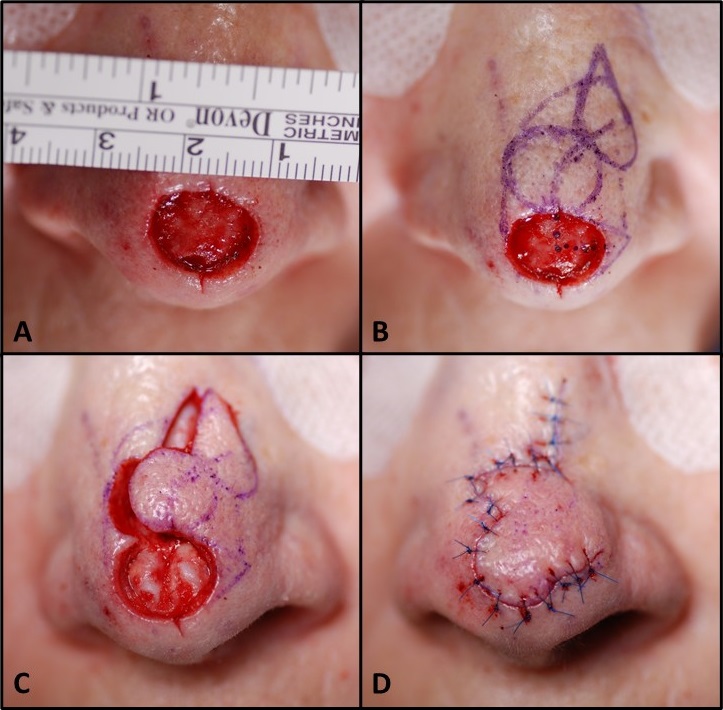

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Bilobed Flap, Zitelli Modification. A) 1.5 cm defect of the nasal tip. B) Superolaterally-based bilobed flap marked. C) Residual tissue in defect removed, flap incised, and elevated in a submuscular plane; note the cartilages of the nasal tip that were not previously visible. D) Flap inset with deep dermal and superficial sutures.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Video to Play)

References

Maher IA. Extrapolating Straight Lines to Curves: Can the Dynamics of Z-Plasties Be Applied to Bilobed and Trilobed Flaps? Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2020 Feb:46(2):277-280. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001947. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30939519]

Kim YH, Yoon HW, Chung S, Chung YK. Reconstruction of cutaneous defects of the nasal tip and alar by two different methods. Archives of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Dec:19(4):260-263. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02271. Epub 2018 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 30613087]

Filitis DC, Fisher J, Samie FH. Reconstruction of a surgical defect in the popliteal fossa: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018:53():228-230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.10.070. Epub 2018 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 30428437]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZitelli JA. The bilobed flap for nasal reconstruction. Archives of dermatology. 1989 Jul:125(7):957-9 [PubMed PMID: 2742390]

Ramanujam CL, Zgonis T. Use of Local Flaps for Soft-Tissue Closure in Diabetic Foot Wounds: A Systematic Review. Foot & ankle specialist. 2019 Jun:12(3):286-293. doi: 10.1177/1938640018803745. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30328715]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKnackstedt T, Lee K, Jellinek NJ. The Differential Use of Bilobed and Trilobed Transposition Flaps in Cutaneous Nasal Reconstructive Surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Aug:142(2):511-519. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004583. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29889736]

Grieco MP, Bertozzi N, Grignaffini E, Raposio E. Nose defects reconstruction with the Zitelli bilobed flap. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia : organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 2018 Apr:153(2):278-282. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.17.05035-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29564875]

Bednarek RS, Sequeira Campos M, Hohman MH, Ramsey ML. Transposition Flaps. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763204]

Couceiro J, De la Red-Gallego M, Yeste L, Ayala H, Sanchez-Crespo M, Velez O, Barcenilla R, Del Canto F. The Bilobed Racquet Flap or Extended Seagull Flap for Thumb Reconstruction: A Case Report. The journal of hand surgery Asian-Pacific volume. 2018 Mar:23(1):128-131. doi: 10.1142/S2424835518720050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29409406]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKelly-Sell M, Hollmig ST, Cook J. The superiorly based bilobed flap for nasal reconstruction. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Feb:78(2):370-376. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.014. Epub 2017 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 29056236]