Introduction

Babesiosis is an infectious disease caused by intraerythrocytic, tick-borne protozoa of the Babesia species.[1][2][3]

In the USA and Europe, the organism Babesia is transmitted following the bite of ticks. Babesia primarily infects animals and humans are only opportunistic hosts. The parasite is also referred to as piroplasms because of its 'pear-shape' that is seen within the infected erythrocytes. In the USA, infection by babesia is rare and only limited to certain geographical regions. Most individuals exhibit no symptoms but certain patients may exhibit high morbidity and mortality. Overall, the disease chiefly affects patients who are splenic, immunocompromised or the elderly.

Babesiosis is not easy to diagnose and a high index of suspicion is required, especially in endemic regions. Treatment is recommended for patients regardless of symptoms to prevent progression and transmission of the disease.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Babesiosis is a parasitic infection caused by protozoa of the genus Babesia. Babesia species have been subdivided into four categories, known as clades. Babesia microti is the most prevalent and well-described species and is classified as a Clade 1 organism. Babesiosis is typically acquired by bites from ticks carrying the protozoa. As the parasite infects erythrocytes (red blood cells), the infection can be acquired through blood transfusion and therefore can occur in persons who have not traveled to endemic areas. Transplacental transmission has also been reported.[4][5]

Babesia typically infects the red blood cells and may appear oval or pear-shaped. The ring form and the peripheral location in the red blood cell often cause misinterpretation of the smear for plasmodium falciparum. However, unlike plasmodium hemolysis is rare in babesiosis. However, the increased aggregation and rigidity of the RBC often leads to the development of acute respiratory distress and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. The fragmentation of the red blood cells can also lead to blockage of the capillaries in many other organs. The spleen is responsible for trapping the damaged red cells and can become enlarged. Patients without a spleen tend to have a more severe course of the disease.

The tick that transmits Babesia, the Ixodes tick, is the same vector that also transmits B.Burgdorferi.

Epidemiology

Of the more than 100 Babesia species known to infect vertebrate animals, only a few have been documented to cause infection in humans. Ixodes ticks are the vector, and the primary reservoirs are typically small vertebrates such as rodents (particularly the white-foot mouse in the U.S.) and birds and the interaction between the vector and primary reservoir is required to complete the organism's life cycle. Larger mammals, particularly deer, sustain the adult population by providing a source of a blood meal but are not reservoir hosts. Humans are accidental and dead-end hosts, and infections tend to occur in late spring through the fall in areas where humans are in proximity to ticks and their reservoirs. The majority of cases of Babesiosis in the United States occur in the Northeast (CT, MA, NJ, NY, RI) and upper Midwest (MN, WI) and are due to Babesia microti, transmitted by the Ixodes scapularis tick. The incidence of infection in this geographic area has been increasing. Babesiosis occurs sporadically in the Pacific Northwest, due to the Ixodes pacificus tick, and caused by the species Babesia duncani. In Europe, babesiosis is typically caused by Babesia divergens.[6][7][8]

Pathophysiology

The nymphal stage of the Ixodes is the primary vector and typically requires attachment to a host for at least 36 to 72 hours to complete a blood meal. If the tick is carrying the protozoa, the second or third day of attachment is typically when the babesia infection occurs with the transmission of sporozoite forms. These sporozoites attach and enter erythrocytes where they mature and divide via binary fission to form merozoites. These merozoites then leave the host erythrocyte, rupturing the cell, and go on to infect other erythrocytes, repeating the cycle above. The spleen is essential in the host's ability to control this infection. Erythrocytes infected with Babesia are recognized as abnormal as they pass through the spleen and are targeted for destruction by macrophages. People with a history of splenectomy are at high risk for severe infection with high-level parasitemia. Other high-risk populations include those with HIV, older than 50 years, neonates, and immunosuppressed patients (particularly TNF inhibitors or CD20 antibody).

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of babesiosis can range from asymptomatic to severe infection causing multi-organ failure. The severity of infection is often dependent on the immunocompetence of the host. The asymptomatic infection has been reported in up to 20% of adults and 50% of children. The incubation period has been reported to be typically between one to six weeks.

Symptomatic illness in patients without immunodeficiencies usually consists of a febrile, flu-like illness often with a chill, sweats, malaise, fatigue, and headache. Other less common symptoms include a cough, arthralgia, sore throat, abdominal pain, nausea, emotional lability, and depression. On exam, apart from fever, patients may have hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, retinopathy, or pharyngeal erythema. A rash is not a common symptom and may indicate co-infection with Lyme disease.

Severe disease typically occurs only in high-risk populations mentioned above, particularly in those with a history of asplenia. These patients may have multi-organ dysfunction, including respiratory distress, congestive heart failure, renal failure, splenic rupture, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), hepatitis, or coma.

Evaluation

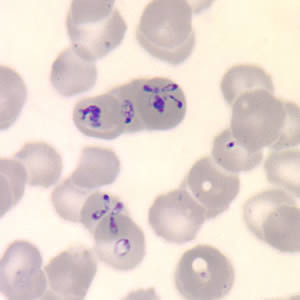

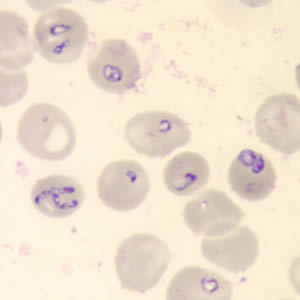

The diagnosis of babesiosis is typically made by identifying the organism on a thin smear of peripheral blood, using Giemsa or Wright staining, and the severity of parasitemia can be assessed. In early infection, it is recommended that multiple thin smears be examined as parasite burden may be low initially. Ring forms are most commonly seen and can have multiple rings per cell. Tetrad formations, also known as Maltese cross, are occasionally seen. PCR testing is also available at reference laboratories and is more sensitive than peripheral smears. Serology is performed via indirect immunofluorescent antibody testing and can be useful for confirming the diagnosis. A single positive serology cannot distinguish between acute and previous infection, but a four-fold rise in acute and convalescent titers confirms a recent infection. Lab abnormalities that may be seen in babesiosis include anemia, elevated LDH, thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, proteinuria, and elevated BUN and creatinine. [9]

Features on a blood smear that suggest babesiosis and plasmodium include the following:

- Lack of brown pigment precipitates

- The rare presence of tetrads

- Absence of synchronous stages (eg, presence of gametocytes and schizonts are often seen with plasmodium)

- Babesia vary in size and shape

- Most are located in the periphery

Treatment / Management

Treatment is indicated in symptomatic cases or in asymptomatic patients who have a positive blood smear or PCR for more than three months. There are two regimens used for treatment in mild to moderate disease. The first and most commonly used regimen is atovaquone plus azithromycin. The other option is quinine plus clindamycin which has much higher rates of adverse drug reactions compared to atovaquone/azithromycin (72% versus 15% respectively). A 7- to 10-day course of either regimen is recommended. Severe disease, requiring hospitalization or causing organ failure, typically occurs in high-risk populations or in those infected with the B. divergens species. These patients require treatment with clindamycin plus quinine (IV quinidine may also be used, but the patient requires monitoring for QT prolongation).

The duration of treatment is at least 7 to 10 days but is based on clinical and laboratory response. Some of these patients with immunocompromising conditions will have persistent or relapsing disease, in which case, a course of at least six weeks is recommended, with treatment continued for at least two weeks after parasites are no longer detected on blood smears. For patients who fail to respond to standard therapy, other regimens have been used including atovaquone plus azithromycin plus clindamycin; atovaquone plus azithromycin plus doxycycline; and atovaquone plus clindamycin plus doxycycline. No particular anti-parasitic combination therapeutic drug regimen has demonstrated superiority. If possible, it is also recommended to reduce underlying immunosuppression. [10]

Partial or complete red blood cell (RBC) exchange transfusion is indicated in patients presenting with a parasitemia of at least 10% and anemia with hemoglobin of <10 g/dL. Consideration for exchange transfusion should be strongly given in those with infection due to B. divergens pulmonary, renal or hepatic dysfunction, regardless of parasitemia level.[11][12]

Respiratory distress is common in severe disease and patients must be monitored in the ICU. The respiratory distress is usually due to endotoxin release following medication-induced lysis of the red cells.

Differential Diagnosis

- Colorado Tick fever

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Malaria

- Ehrlichiosis

- Q fever

- Anemia

- Typhoid fever

Prognosis

The prognosis of babesiosis depends on the type of symptoms. Most patients remain asymptomatic and have a good outcome. Others may have a flu-like infection, which is also associated with a good outcome. However, those with severe disease can have a long course complicated with multiorgan dysfunction and death. Fatalities are most common in patients without a spleen

The symptoms of babesiosis may last for 6-8 weeks and asymptomatic patients may remain silent for years. All patients with positive smears three months after the initial treatment must be re-treated, even in the absence of seizures.

About 1/5th of patients with babesiosis may be co-infected with Lyme disease. These patients tend to have a more prolonged course.

Complications

Most complications are related to the intravascular hemolysis and include:

- Jaundice

- Shock

- Hemoglobinuria

- Splenic rupture

- Death

- ARDS

- Renal dysfunction

- Noncardiogenic heart failure

Pearls and Other Issues

Babesiosis became a reportable disease in the United States in January 2011, and its incidence has been increasing, due in part to a geographic expansion of the vector. Because Ixodes scapularis is also the vector for Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, coinfections do occur and should especially be considered in patients failing to improve on therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Babesiosis is a rare tick-borne infection with a varied presentation. The organism can affect many organ systems and is best managed by an interprofessional team. The diagnosis is not easy and can be confused with malaria or other tick-borne disorder. Asymptomatic patients do not need treatment but must be followed because treatment is required if the parasitemia persists for more than 3 months.

As soon as the infection is diagnosed, it has to be reported to the local public health authority and the infectious disease expert should be consulted on management.

The pharmacist should educate the patient on the need for antibiotic compliance. In addition, the nurse should instruct the patient on preventive methods when traveling to certain parts of the USA. Avoidance of tick bite is the key. This can be done by wearing appropriate garments.

Delayed diagnosis can lead to high morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with no spleen. Interprofessional teamwork is key in the diagnosis and management of this condition.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Patel KM, Johnson JE, Reece R, Mermel LA. Babesiosis-associated Splenic Rupture: Case Series From a Hyperendemic Region. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2019 Sep 13:69(7):1212-1217. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30541016]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTonnetti L, Townsend RL, Deisting BM, Haynes JM, Dodd RY, Stramer SL. The impact of Babesia microti blood donation screening. Transfusion. 2019 Feb:59(2):593-600. doi: 10.1111/trf.15043. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30499595]

Beard CB, Occi J, Bonilla DL, Egizi AM, Fonseca DM, Mertins JW, Backenson BP, Bajwa WI, Barbarin AM, Bertone MA, Brown J, Connally NP, Connell ND, Eisen RJ, Falco RC, James AM, Krell RK, Lahmers K, Lewis N, Little SE, Neault M, Pérez de León AA, Randall AR, Ruder MG, Saleh MN, Schappach BL, Schroeder BA, Seraphin LL, Wehtje M, Wormser GP, Yabsley MJ, Halperin W. Multistate Infestation with the Exotic Disease-Vector Tick Haemaphysalis longicornis - United States, August 2017-September 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018 Nov 30:67(47):1310-1313. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6747a3. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30496158]

Abraham A, Brasov I, Thekkiniath J, Kilian N, Lawres L, Gao R, DeBus K, He L, Yu X, Zhu G, Graham MM, Liu X, Molestina R, Ben Mamoun C. Establishment of a continuous in vitro culture of Babesia duncani in human erythrocytes reveals unusually high tolerance to recommended therapies. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2018 Dec 28:293(52):19974-19981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC118.005771. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30463941]

Villatoro T, Karp JK. Transfusion-Transmitted Babesiosis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2019 Jan:143(1):130-134. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0250-RS. Epub 2018 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 30376376]

Leiby DA, O'Brien SF, Wendel S, Nguyen ML, Delage G, Devare SG, Hardiman A, Nakhasi HL, Sauleda S, Bloch EM, WPTTID Subgroup on Parasites. International survey on the impact of parasitic infections: frequency of transmission and current mitigation strategies. Vox sanguinis. 2019 Jan:114(1):17-27. doi: 10.1111/vox.12727. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30523642]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRautenbach Y, Schoeman J, Goddard A. Prevalence of canine Babesia and Ehrlichia co-infection and the predictive value of haematology. The Onderstepoort journal of veterinary research. 2018 Oct 9:85(1):e1-e5. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v85i1.1626. Epub 2018 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 30326715]

Gray JS, Estrada-Peña A, Zintl A. Vectors of Babesiosis. Annual review of entomology. 2019 Jan 7:64():149-165. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011118-111932. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30272993]

Hoversten K, Bartlett MA. Diagnosis of a tick-borne coinfection in a patient with persistent symptoms following treatment for Lyme disease. BMJ case reports. 2018 Sep 27:2018():. pii: bcr-2018-225342. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225342. Epub 2018 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 30262525]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaparone P,Paparone PW, Variable clinical presentations of babesiosis. The Nurse practitioner. 2018 Oct [PubMed PMID: 30234826]

Lempereur L, Beck R, Fonseca I, Marques C, Duarte A, Santos M, Zúquete S, Gomes J, Walder G, Domingos A, Antunes S, Baneth G, Silaghi C, Holman P, Zintl A. Guidelines for the Detection of Babesia and Theileria Parasites. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont, N.Y.). 2017 Jan:17(1):51-65. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.1955. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28055573]

Choi E, Pyzocha NJ, Maurer DM. Tick-Borne Illnesses. Current sports medicine reports. 2016 Mar-Apr:15(2):98-104. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000238. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26963018]