Introduction

Edema refers to excessive fluid accumulation in the interstitial spaces, beneath the skin, or within the body cavities caused by any of the following and producing significant signs and symptoms.[1]

- An imbalance among the "Starling forces."

- Damage/blockage of the draining lymphatic system

The affected body part usually swells if edema is present beneath the skin or produces significant signs and symptoms related to the body cavity involved.

There are several different types of edema, and a few important ones are peripheral edema, pulmonary edema, cerebral edema, macular edema, and lymphedema. The atypical forms are idiopathic edema and hereditary angioneurotic edema.

Pulmonary edema refers to the accumulation of excessive fluid in the alveolar walls and alveolar spaces of the lungs. It can be a life-threatening condition in some patients.[2] Pulmonary edema can be:

- Cardiogenic (disturbed starling forces involving the pulmonary vasculature and interstitium)

- Non-cardiogenic (direct injury/damage to lung parenchyma/vasculature)

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

All the factors that contribute to increased pressure on the left side and the pooling of blood on the left side of the heart can cause cardiogenic pulmonary edema.[3] The result of all these conditions will be increased pressure on the left side of the heart: increased pulmonary venous pressure--> increased capillary pressure in lungs--> pulmonary edema.[4]

- Coronary artery disease with left ventricular failure (myocardial infarction)

- Congestive heart failure

- Cardiomyopathy

- Valvular heart diseases on the left side of the heart (stenosis and regurgitation)

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Right to left shunts

Epidemiology

Pulmonary edema is a life-threatening condition with an estimated 75000 to 83000 cases per 100000 persons having heart failure and low ejection fraction. A trial showed an alarming 80% prevalence of pulmonary edema in patients with heart failure.[5] It is a troublesome condition with the rate of discharge being 74% and the rate of survival after one year of 50%.[6]. The mortality rate at six years follow-up was 85% with patients with congestive heart failure. Males are typically affected more than females, and older patients are at a higher risk for developing pulmonary edema.[7]

Pathophysiology

The cardiogenic form of pulmonary edema (pressure-induced) produces a non-inflammatory type of edema by the disturbance in Starling forces. The pulmonary capillary pressure is 10mm Hg (range: 6 to 13) in normal conditions, but any factor that increases this pressure can cause pulmonary edema.[8] The alveoli are normally kept dry because of the negative pressure in extra-alveolar interstitial spaces, but when there is[9]:

Increased pressure/pooling--> Increased pulmonary venous pressure--> Increased pulmonary capillary pressure--> fluid in interstitial spaces--> Increased pressure in interstitial spaces--> fluid in alveoli (pulmonary edema).

Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure can be measured and graded and will produce different presentations on X-rays.

Histopathology

The main features seen on microscopy are[10]:

- Alveolar wall thickening

- Dilated capillaries and interstitial edema

- Transudation in the alveolar lumen (granular and pale eosinophilic)

History and Physical

Patients usually present with shortness of breath, which may be acute in onset (from minutes to hours) or gradual in onset, occurring over hours to days, depending upon the etiology of pulmonary edema.

Acute pulmonary edema will have[11]:

- Excessive shortness of breath worsening on exertion or lying down

- A feeling of the heart sinking and drowning/anxiety worsening on lying down

- Gasping for breath

- Dizziness and excessive sweating

- A cough may be associated with worsening edema

- Blood-tinged/pink-colored frothy sputum in very severe disease

- Chest pain (myocardial infarction and aortic dissection)

- Cold, clammy skin

Chronic pulmonary edema will have the following:

- Shortness of breath on exertion

- Orthopnea

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Swelling of the body/lower extremities

- Weight gain

- Fatigue

Ortner syndrome, which refers to hoarseness due to compression of recurrent laryngeal nerve because of an enlarged left atrium, may also be occasionally present in some patients.

Physical Examination

On examination, the positive findings include:

- General appearance

Confusion, agitation, and irritability may be present, associated with excessive sweating, cold extremities, upright posture (sitting upright), and cyanosis of the lips.

- JVP/JVD

Usually raised.

-

Blood Pressure

Hypertension is more often present, but if hypotension prevails, it is an indicator of severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and cardiogenic shock must be ruled out. Cold extremities are a feature of low perfusion and shock.

- Respiratory Rate

Tachypnea is usually present, with the patient gasping for breath.

- Pulse

Tachycardia (increased heart/ pulse rate) and associated finding of the cause in the pulse.

- Pedal Edema

Usually co-exists with pulmonary edema in chronic heart failure.

- Respiratory Findings

Dyspnea and tachypnea are usually present and may be associated with the use of accessory muscles for respiration. Fine crackles are usually heard at the bases of the lungs bilaterally and progress apically as the edema worsens. Ronchi and wheezing may also be presenting signs.

- Cardiovascular Findings

- Tachycardia and hypotension may be present along with jugular venous distention. Auscultation of the heart helps to differentiate between the various causes of valvular lesions causing pulmonary edema.

- Auscultation typically reveals an S3 gallop in volume overload states, which may be associated with accentuation of the pulmonic component of S2.

- Several different types of murmurs can be heard depending on the cause of the valvular lesion.

- Mitral stenosis produces a low-pitched, rumbling diastolic murmur associated with an opening snap at the apex, which becomes accentuated on expiration and produces loud S1.

- Mitral regurgitation produces a blowing, high-pitched pan-systolic murmur best heard at the apex, radiating to the left axilla and accentuating on expiration, producing soft S1.

- Aortic stenosis produces a harsh crescendo-decrescendo ejection systolic murmur at the aortic area, increasing on expiration, usually radiating towards the right side of the neck.

- Aortic regurgitation produces a high-pitched blowing early diastolic murmur best heard in the aortic area, greatest during expiration.

- Gastrointestinal System

Tender hepatomegaly may be a feature in cases of right-sided cardiac failure, which may worsen to hepatic fibrosis and hepatic cirrhosis in chronic congestion. Ascites may sometimes be present.

Evaluation

No single definitive test is available for diagnosing pulmonary edema, but clinically, one proceeds from simple to more complex tests while searching for the diagnosis and the associated etiology.

Blood Tests[12]

- CBC (to rule out anemia and sepsis)

- Serum electrolytes (patients on diuretic therapy may have disturbances )

- Pulse oximetry and ABGs (assessing hypoxia and oxygen saturation)

- BNP (brain natriuretic peptide levels: low levels rule out cardiogenic type )

ECG

Used to rule out ischemic changes and rhythm abnormalities.

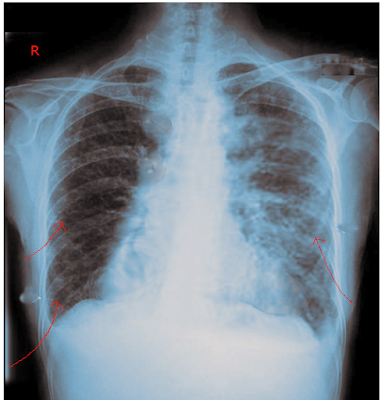

Radiologic Investigations[13]

Chest X-ray (It is one of the most important investigations required for the evaluation of pulmonary edema and overload states.

Early Stage

- In the early stages, cardiomegaly is present, usually identified as an increase of cardiothoracic ratio over 50%.

- Broad vascular pedicle

- Vascular redistribution

- Cephalization

Intermediate Stage

- Interstitial edema

- Kerley B lines

- Peribronchial cuffing

- Thickened interlobar fissure

Late Stage

- Alveolar edema

- Perihilar batwing appearance

- Pleural effusion

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography may be helpful in further strengthening of diagnosis. Transthoracic ultrasound usually differentiates COPD from CCF as a cause of acute exacerbation of chronic dyspnea.

Echocardiography[14]

Extremely important in determining the etiology of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. It differentiates systolic from diastolic dysfunction and valvular lesions.

- Cardiac tamponade

- Acute papillary muscle rupture

- Acute ventricular septal defect

- Valvular lesions

Invasive Technique

Pulmonary Arterial Catheter

A Swan-Ganz catheter is inserted into the peripheral vein and advanced until the branch of the pulmonary artery is reached, and then the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is measured.

Treatment / Management

General Management[15]

ABC must be addressed initially as the patient arrives.

- Airway assessment ( Make sure the airway is clear for adequate oxygenation and ventilation)

- Breathing ( Note the pattern of breathing and oxygen saturation.)

- Circulation ( Vital signs and cardiac assessment and management )

- Oxygen delivery and ventilatory support (Through nasal cannula, face mask, non-rebreather mask, noninvasive pressure support ventilation, and mechanical ventilation as required)

- Prop up

- Intravenous access

- Urine output monitoring

After initial airway clearance, oxygenation assessment, and maintenance, management mainly depends upon presentation and should be tailored from patient to patient. Supplemental oxygen is a requirement if the patient is at risk of hypoxemia (SPO2 less than 90% ). Unnecessary oxygen should not be administered as it causes vasoconstriction and reduction in cardiac output. Supplemental oxygen, if necessary, should be given in the following order:

Nasal cannula and face mask ---> Non-rebreather mask ---> Trial of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) ---> Intubation and mechanical ventilation

If the respiratory distress and hypoxemia continue on oxygen supplementation, a trial of non-invasive ventilation should follow if there are no contraindications of NIV, as evidence suggests that it lowers the need for intubation and improves respiratory parameters. If the patient does not improve or has contraindications to NIV, then intubation and mechanical ventilation (with high positive end-expiratory pressure) should be considered.

- Treatment of the underlying cause.

- Non Invasive Management

- Invasive Management

Non-Invasive Management[18] can be achieved by:

- Pre-Load Reduction which can be achieved by:

- Nitroglycerin

- Sodium nitroprusside

- Isosorbide dinitrate

- Loop diuretics (furosemide, torsemide, bumetanide)

- Morphine and nesiritide require extreme care.

- BIPAP can help move the fluid out of the lungs by increasing the intrapulmonary pressure

After initial resuscitation and management, the mainstay of treatment in acute settings is diuresis with or without vasodilatory therapy. The aggressiveness of treatment depends upon the initial presentation, hemodynamic, and volume status of the patient. VTE prophylaxis is generally indicated in patients admitted with acute heart failure. Sodium restriction is also necessary for patients with HF.

Patients presenting with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) with features of pulmonary edema should be treated with intravenous diuretics initially, regardless of the etiology. Patients with HF and features of pulmonary edema receiving treatment with early administration of diuretics had better outcomes according to guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force.[19] A prospective observational study suggested that early treatment with furosemide in patients with AHF lowers in-hospital mortality, and the mortality increases with a delay in the time of administration.[20] Diuretic therapy for patients who have not received diuretics previously is as follows:(A1)

If renal function is adequate:

- Furosemide: 20 to 40 mg IV

- Torsemide: 10 to 20 mg IV

- Bumetanide: 1 mg IV

If renal function is deranged/severe HF:

- Furosemide: up to 160 to 200 mg IV bolus, or can be given as 5 to 10mg/hr drip.

- Torsemide: up to 100 to 200 mg IV bolus

- Bumetanide: 4 to 8 mg IV bolus

If the patient shows normal renal function, and there is very little/no response to initial treatment, the dose of diuretics should be doubled at 2-hour intervals until achieving the maximum recommended.

The patients who are on chronic diuretic therapy should receive higher doses of diuretics in acute settings. The initial dose for such patients should be greater than two times of daily maintenance dose. A continuous infusion can also be used as an alternative to bolus therapy if the patient responds to the bolus dose.

While being managed in the hospital for pulmonary edema, IV diuresis can be used using loop diuretics. Furosemide is the usual drug of choice. While diuresis, one should monitor the following:

- Daily weight

- Strict intake and output measures

- Telemetry

- A basic metabolic panel including kidney functions and electrolytes

- Keep serum potassium above 4.0 mEq/L and Mg over 2.0 mEq/L.

- Continuous pulse ox if indicated

- Renal functions

In addition to diuretic therapy, vasodilator therapy may be necessary. Indications include:

- Urgent afterload reduction ( severe hypertension )

- Adjunct to diuretics when the patient doesn't respond to diuretic therapy alone

- For patients with refractory heart failure and decreased cardiac output

Vasodilator therapy has to be used with great caution since it can cause symptomatic hypotension, and the evidence of its efficacy and safety is very limited. When they are needed, they should be used with great caution while monitoring hemodynamic response under expert opinion.

Nitrates (nitroglycerin and isosorbide dinitrate) cause greater venodilation than arterio-dilation and can be used intravenously in recommended doses. Nitroglycerin can be used at 5 to 10 mcg/min initially and can be increased gradually to the maximum recommended dose (200 mcg/min) while closely monitoring the hemodynamic responses. Isosorbide dinitrate has a much longer half-life than nitroglycerin, which puts it at a disadvantage if the drug requires discontinuation because of symptomatic hypotension.

Sodium nitroprusside causes both venous and arterio-dilation and can significantly lower blood pressure. It requires close hemodynamic monitoring through an intra-arterial catheter. It is used initially in a dose of 5 to 10 mcg/min, which can be titrated up to 400 mcg/min, which is the maximum recommended dose. At higher doses, it increases the risk of cyanide toxicity. Hence, it has to be used with extreme caution and with close monitoring under expert supervision.

Nesiritide should not routinely be a therapeutic option for the treatment of HF. A large randomized trial fusing nesiritide in patients of acutely decompensated heart failure (ADHF) shows that it was not associated with any change in the rate of death or rehospitalization, increased risk of hypotension, and a small non-significant change in dyspnea.[21] Nesiritide, if used, should be used initially as an intravenous bolus of 2 mcg/kg and afterward a continuous infusion of 0.01 mcg/kg.(A1)

Salt and water restriction is generally indicated for patients with HF.

Vasopressor receptor antagonist (tolvaptan) can also be used with caution and under supervision.

- After-Load Reduction which can be achieved by:

- ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI): captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, perindopril, etc.

- ARBs (angiotensin receptor blockers): valsartan, telmisartan, olmesartan, candesartan, etc.

- Sodium nitroprusside

ACE inhibitors, or ARNI, are the mainstay of chronic treatment for patients with HFrEF. If the patient doesn't tolerate ACE inhibitors or ARNI, then ARB should be considered the first-line choice for prolonged treatment. Beta-blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists require extra care if used.

If blood pressure is low, start ionotropic agents, and vasopressors (catecholamines and phosphodiesterase inhibitors) should commence. The treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) differs from heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. (HFpEF).

For patients of HFrEF presenting with hypotension, intense hemodynamic monitoring is necessary. The patient should undergo evaluation for signs of shock (confusion, cold extremities, decreased urine output, etc.). If the patient of HFrEF has signs of hypotension and/or blood pressure less than 80mmg, Ionotropes should be added immediately and titrated accordingly. For patients with persistent shock, vasopressors also have to be added.

For patients with HFpEF, only vasopressors are necessary. Inotropes are NOT indicated in patients with HFpEF and dynamic left ventricular obstruction (most commonly hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy).

Invasive Management[14]

- IABP (intra-aortic balloon pump)

- Ultrafiltration

- Ventricular assist devices

- ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation)

- Cardiac transplant

- Valve replacement (in case of valvular issues)

- PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention)

- CABG (coronary artery bypass graft)

- Intubation (if required to maintain the airway and also helps in moving the fluid out)

In a patient of severe HFrEF with acute hemodynamic compromise and cardiogenic shock, mechanical cardiac support is available while waiting on a decision or waiting on recovery, hence called " bridge to the decision and "bridge to recovery." The patients usually have blood pressure less than 90mmHg, PCWP greater than 18mmHg, and a cardiac index of less than 2L/min per meter square.

IABP (intra-aortic balloon pump) is the device that is used most commonly among mechanical circulatory devices as it is the least expensive, easily insertable, and readily available. It consists of a balloon in the aorta that inflates and deflates synchronously with the heartbeat, causing increased cardiac output and coronary flow. IABPs are commonly used for temporary circulatory support with patients with advanced heart failure while waiting for a heart transplant or VADs. It is not a definitive therapy but is widely used as a bridge therapy for patients with cardiogenic shock and also as an adjunct to thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction for stabilization.

Ventricular assist devices, as compared to IABP, have greater efficacy in increasing the hemodynamic parameters. These have more complications and require more expertise, take longer to insert and cost more in comparison. They are an option in acute decompensated heart failure. They can also be useful in complications of acute heart failure like cardiogenic shock, mitral regurgitation, and VSDs. They can be different kinds, like the left ventricle to the aorta, the left atrium to the aorta, the right ventricular assist device, etc.

Ultrafiltration (UF) is the most effective approach for sodium, and water removal effectively improves hemodynamics in patients with heart failure. UF is the process of abstracting plasma water from the whole blood across a hemofilter because of the transmembrane pressure gradient. It is preferred over diuretics because it removes sodium and water more effectively and does not stimulate neurohormonal activation through macula densa. UF is used in patients with HF as it decreases PCWP, restores diuresis, reduces diuretic requirements, corrects hyponatremia, improves cardiac output, and thus improves congestion.[22] In some patients with heart failure, UF was associated with improved cardiac index and oxygenation capacity, decreased PCWP, and less need for inotropes.[23] Several types of UF are isolated, intermittent, and continuous. The continuous type can work in an arterio-venous or veno-venous mode, which is the most common type.

UF can be crucial in patients with heart failure and resistance to diuretic therapy and can serve to optimize the volume status. Many questions regarding UF require examination in further studies, and the evidence does not support its widespread use as a substitute for diuretics.[24]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis includes[25]:

- Respiratory failure

- Myocardial ischemia/infarct

- Pulmonary embolism

- Neurogenic pulmonary edema

- High-altitude pulmonary edema

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Prognosis

Prognosis mainly depends on the underlying cause but generally has a poor prognosis. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema is an alarming condition with the rate of discharge being 74% and the rate of survival after one year of 50%.[6] The mortality rate at 6 years follow-up is 85% with patients of congestive heart failure.[7]

Complications

Most complications of pulmonary edema arise from the complications of the underlying cause. Common complications associated with cardiogenic etiologies include:

- Risk of arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardias)

- Thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism, DVT, stroke)

- Pericarditis

- Rupture

- Valvular heart disease

- Cardiogenic shock

- Tamponade

- Dressler syndrome

- Death

Pulmonary edema can cause severe hypoxia and hypoxemia, leading to end-organ damage and multi-organ failure. Respiratory failure is another common complication of cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As cardiac events are the prime factors for the development of pulmonary edema, patients are advised to control and prevent the progression of heart disease by:

- Healthy lifestyle and exercise

- Smoking cessation

- Alcohol cessation

- Weight reduction and monitoring

- Proper diet control

- Low cholesterol diet

- Reducing salt intake

- Blood pressure control

- Good glycemic control

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pulmonary edema can be a very life-threatening condition, and specialized consultation is a requirement for diagnosis and management. Considering a very high short-term mortality rate, an Interprofessional team approach is recommended in the management of these patients to improve outcomes.

Starting from the diagnosis, etiological factor, and management of the patient, a well-coordinated team needs to work for better patient care involving all the related departments. All the available treatment options need to be discussed to avoid any complications and improve the outcome. The use of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation has a significant benefit in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema.[26] [Level-2]

While the physician is involved primarily in the management of the patient, consultation is also necessary from a team of specialists involving cardiologists, pulmonologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons. The nurses are also vital members of the interprofessional group, as they will monitor the patient's vital signs and communicate back to the team with results. The nurse practitioner, like the primary care provider, follows these patients in an outpatient setting and should try and reduce the risk factors for ischemic heart disease. Patients should be urged to quit smoking, enroll in cardiac rehabilitation, maintain a healthy body weight, become physically active, and remain compliant with follow-up appointments and medications. A dietary consult should be obtained to educate the patient on a healthy diet and what foods to avoid.

Since most patients with heart failure are no longer able to work, social work assistance is crucial so that the patient can get the much-needed medical support.

The role of pharmacists will be to ensure that the patient is on the right medication and dosage. The radiologist can also play a vital role in determining the cause of dyspnea. A mental health nurse should consult with the patient because depression and anxiety are common morbidities, leading to poor quality of life.

As shown above, cardiogenic pulmonary edema requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, other ancillary therapists (respiratory, social worker), and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]

If the patient is deemed to be a candidate for a ventricular assist device or heart transplant, the transplant nurse should be involved early in the care. With a shortage of organs, one also has to be realistic with patients.

At the moment, the role of morphine and nesiritide remains questionable and requires further evaluation.[27][28]

Outcomes

Unfortunately, despite optimal treatment, the outcomes for cardiogenic pulmonary edema/heart failure are abysmal. There is no cure for this disorder, and the key is to prevent the condition in the first place.

Media

References

Trayes KP, Studdiford JS, Pickle S, Tully AS. Edema: diagnosis and management. American family physician. 2013 Jul 15:88(2):102-10 [PubMed PMID: 23939641]

Powell J, Graham D, O'Reilly S, Punton G. Acute pulmonary oedema. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2016 Feb 3:30(23):51-9; quiz 60. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.23.51.s47. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26838657]

Sureka B, Bansal K, Arora A. Pulmonary edema - cardiogenic or noncardiogenic? Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2015 Apr-Jun:4(2):290. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154684. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25949989]

Alwi I. Diagnosis and management of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Acta medica Indonesiana. 2010 Jul:42(3):176-84 [PubMed PMID: 20973297]

Platz E, Jhund PS, Campbell RT, McMurray JJ. Assessment and prevalence of pulmonary oedema in contemporary acute heart failure trials: a systematic review. European journal of heart failure. 2015 Sep:17(9):906-16. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.321. Epub 2015 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 26230356]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCrane SD. Epidemiology, treatment and outcome of acidotic, acute, cardiogenic pulmonary oedema presenting to an emergency department. European journal of emergency medicine : official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2002 Dec:9(4):320-4 [PubMed PMID: 12501030]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWiener RS, Moses HW, Richeson JF, Gatewood RP Jr. Hospital and long-term survival of patients with acute pulmonary edema associated with coronary artery disease. The American journal of cardiology. 1987 Jul 1:60(1):33-5 [PubMed PMID: 3604942]

Murray JF. Pulmonary edema: pathophysiology and diagnosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011 Feb:15(2):155-60, i [PubMed PMID: 21219673]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSibbald WJ, Anderson RR, Holliday RL. Pathogenesis of pulmonary edema associated with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Canadian Medical Association journal. 1979 Feb 17:120(4):445-50 [PubMed PMID: 376080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiles WA. Pulmonary edema: an anatomic, pathophysiologic, and roentgenologic analysis. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1977 Mar:69(3):179-82 [PubMed PMID: 875070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuntupalli KK. Acute pulmonary edema. Cardiology clinics. 1984 May:2(2):183-200 [PubMed PMID: 6443344]

Mattu A, Martinez JP, Kelly BS. Modern management of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2005 Nov:23(4):1105-25 [PubMed PMID: 16199340]

Matsuyama S, Ootaki M, Saito T, Iino M, Kano M. [Radiographic diagnosis of cardiogenic pulmonary edema]. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai zasshi. Nippon acta radiologica. 1999 May:59(6):223-30 [PubMed PMID: 10388306]

Johnson MR. Acute Pulmonary Edema. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 1999 Oct:1(3):269-276 [PubMed PMID: 11096492]

Sánchez Marteles M, Urrutia A. [Acute heart failure: acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock]. Medicina clinica. 2014 Mar:142 Suppl 1():14-9. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7753(14)70077-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24930078]

Baird A. Acute pulmonary oedema - management in general practice. Australian family physician. 2010 Dec:39(12):910-4 [PubMed PMID: 21301670]

Chioncel O, Collins SP, Ambrosy AP, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G. Pulmonary Oedema-Therapeutic Targets. Cardiac failure review. 2015 Apr:1(1):38-45. doi: 10.15420/CFR.2015.01.01.38. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28785430]

Johnson JM. Management of acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: a literature review. Advanced emergency nursing journal. 2009 Jan-Mar:31(1):36-43. doi: 10.1097/TME.0b013e3181946fd8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20118852]

WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Oct 15:128(16):e240-327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. Epub 2013 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 23741058]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMatsue Y, Damman K, Voors AA, Kagiyama N, Yamaguchi T, Kuroda S, Okumura T, Kida K, Mizuno A, Oishi S, Inuzuka Y, Akiyama E, Matsukawa R, Kato K, Suzuki S, Naruke T, Yoshioka K, Miyoshi T, Baba Y, Yamamoto M, Murai K, Mizutani K, Yoshida K, Kitai T. Time-to-Furosemide Treatment and Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Heart Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Jun 27:69(25):3042-3051. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.042. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28641794]

O'Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, Armstrong PW, Dickstein K, Hasselblad V, Heizer GM, Komajda M, Massie BM, McMurray JJ, Nieminen MS, Reist CJ, Rouleau JL, Swedberg K, Adams KF Jr, Anker SD, Atar D, Battler A, Botero R, Bohidar NR, Butler J, Clausell N, Corbalán R, Costanzo MR, Dahlstrom U, Deckelbaum LI, Diaz R, Dunlap ME, Ezekowitz JA, Feldman D, Felker GM, Fonarow GC, Gennevois D, Gottlieb SS, Hill JA, Hollander JE, Howlett JG, Hudson MP, Kociol RD, Krum H, Laucevicius A, Levy WC, Méndez GF, Metra M, Mittal S, Oh BH, Pereira NL, Ponikowski P, Tang WH, Tanomsup S, Teerlink JR, Triposkiadis F, Troughton RW, Voors AA, Whellan DJ, Zannad F, Califf RM. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Jul 7:365(1):32-43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100171. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21732835]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarenzi G, Grazi S, Giraldi F, Lauri G, Perego G, Guazzi M, Salvioni A, Guazzi MD. Interrelation of humoral factors, hemodynamics, and fluid and salt metabolism in congestive heart failure: effects of extracorporeal ultrafiltration. The American journal of medicine. 1993 Jan:94(1):49-56 [PubMed PMID: 8420299]

Coraim FI, Wolner E. Continuous hemofiltration for the failing heart. New horizons (Baltimore, Md.). 1995 Nov:3(4):725-31 [PubMed PMID: 8574603]

Fiaccadori E, Regolisti G, Maggiore U, Parenti E, Cremaschi E, Detrenis S, Caiazza A, Cabassi A. Ultrafiltration in heart failure. American heart journal. 2011 Mar:161(3):439-49. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.09.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21392597]

Komiya K, Akaba T, Kozaki Y, Kadota JI, Rubin BK. A systematic review of diagnostic methods to differentiate acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome from cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Critical care (London, England). 2017 Aug 25:21(1):228. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1809-8. Epub 2017 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 28841896]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePotts JM. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation: effect on mortality in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema: a pragmatic meta-analysis. Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 2009 Jun:119(6):349-53 [PubMed PMID: 19694215]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEllingsrud C, Agewall S. Morphine in the treatment of acute pulmonary oedema--Why? International journal of cardiology. 2016 Jan 1:202():870-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.014. Epub 2015 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 26476045]

Howlett JG. Current treatment options for early management in acute decompensated heart failure. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2008 Jul:24 Suppl B(Suppl B):9B-14B [PubMed PMID: 18629382]