Introduction

Perimetry is a critical diagnostic tool for detecting and evaluating visual field defects, playing a key role in diagnosing and monitoring glaucoma progression.[1] This article discusses the process of perimetry and the interpretation of the visual field printouts (Humphrey visual field analyzer). The history of visual field analysis dates back 2000 years, when Hippocrates first reported a case of hemianopsia.[2]

Successively, Ulmus was the first to publish an illustration of visual fields. Albrecht von Graefe was the first to publish visual field defects characteristic of glaucoma. However, he attributed the field defects at that time to amblyopia due to a lack of knowledge about glaucoma. Landesberg was the first to describe the arcuate defect of glaucoma.[3] The field defect corresponds to the arcuate-like arrangement of the axons emerging from the optic disc.[4]

Jannik Bjerrum used a tangent screen to map the details of the central 30° diameter of the visual field. In subsequent years, Hans Goldmann developed a bowl perimeter that provided a uniform background illumination and a moving optical projection system that could superimpose bright stimuli on the background. Later, Franz Fankhauser, Drs John Lynn, and George Tate were the first to automate the process of perimetry.[5]

Procedures

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Procedures

Visual Field

The visual field is the extent of an area visible to an individual during steady eye fixation in any one gaze or direction. Harry Traquair defined it as "an island of vision surrounded by a sea of blindness," also known as the hill of vision, considering its 3-dimensional aspect. The apex of the hill of vision is the area with the highest retinal sensitivity and represents the fovea. The sensitivity decreases as we move to the periphery of the retina.

Thomas Young gave the extent of a uniocular visual field.[2] This consists of the central 30° field and extends to 60° superiorly and medially. The temporal extension is up to 100°, and the inferior extent is up to 80°. Binocular visual fields extend temporally to 200° with a central overlap of 120°. Edme Mariotte was the first to report that the physiologic blind spot corresponds to the location of the optic disc.[2] The blind spot is located between 10° to 20° temporal to the point of fixation. The physiological blind spot due to the optic disc is called the 'punctum caecum' or 'Mariotte's spot.'[6] A "scotoma" refers to a localized area of vision loss within the visual field, essentially a "blind spot." In contrast, a "field defect" is a broader term encompassing any loss of vision in a part of the visual field, which could include multiple scotomas or a larger area of reduced vision across the field; essentially, a scotoma is a specific type of field defect where vision loss is concentrated in a small, defined area.

Measurement of Visual Field or Perimetry

The measurement of the retina's sensitivity to light is shown at a given location in the visual field printout. The sensitivity of the retina of a healthy individual is highest at the fovea and then reduces towards the periphery.[7] The intensity of the light stimulus is measured in apostilb. However, apostilb and retinal sensitivity are inversely proportional to each other. Also, the human eye responds to a wide range of apostilbs. Therefore, the sensitivity to light is measured in decibels (0-50 in standard automated perimetry). Decibel is the logarithmic representation of the intensity of the light stimulus. This is an adaptation of the Weber-Fechner law, which explains that sensation increases as the logarithm of the stimulus.[8] Decibel has a direct correlation to the sensitivity of the retina. Zero decibels (dB) represent the brightest light stimulus (10,000 apostilbs in Humphrey field analyzer), and 50 dB means the dimmest stimulus (0.1 apostilbs in Humphrey field analyzer). So, a zero decibel (0 dB) stimulus will be visible to a point on the retina with the lowest sensitivity and vice versa. If the 0 dB stimulus is not seen, that denotes an absolute scotoma.

The decibel value is relative, so it varies from machine to machine. A 0 dB reading represents 10,000 apostilbs on the Humphrey visual field analyzer, whereas it represents 4000 apostilbs on the Octopus perimetry. A 40 dB reading represents 1 apostilb on the Humphrey visual Analyzer and 0.4 apostilbs on the Octopus perimetry.

Threshold

This is the intensity of the light stimulus, which, when presented at a particular location, is detected by the corresponding retinal point at least 50% of the time. The threshold is measured by using the staircase method "4-2-1". There are 2 ways to use this method. If the initial stimulus is not seen, then the intensity of the stimulus is increased by 4 dB steps until it is seen. Once visible, 2 dB steps reduce the intensity until it is again not visible. Then, increase the intensity by 1 dB until it is visualized again. This final dB reading is the threshold.[1]

Alternatively, the intensity of a seen stimulus is reduced by 4 dB until it is not visible. Then, the intensity is increased by 2 dB until it is seen and then reduced again by 1 dB until it is not seen. If the threshold at each retinal point was evaluated in 1 dB steps, it would take a lot of time, and the process would tire out the patient easily. Therefore, the staircase method is used.

Kinetic perimetry

The examiner actively performs the test by moving the target on an arc, and the patient responds by localizing the target when it enters the patient's visual field. In this test, the intensity of the target remains the same throughout the test, whereas the color or size of the stimulus can vary. So, this test is useful in assessing the 2-dimensional extent of the visual field. The commonly used kinetic perimeter is the Goldmann perimeter.

Static perimetry

This test is automated.[9][10] The machine presents a stimulus of a particular size but with varying intensity at various locations in a bowl perimeter. The patient responds by pressing a button when they visualize the particular stimulus. The size is constant for one particular test but can be changed between tests. This test measures the depth of the defect at various locations in the visual field. The commonly used static perimeters are the Humphrey and the Octopus.

Strategy

These are testing algorithms used so that the test does not take too long and the patient's fatigue does not affect the results.[11] For example, full threshold, SITA (Swedish interactive thresholding algorithm) standard, and SITA Fast are the different strategies available on the Humphrey field analyzer.[12][13][14]

Program

A reduced number of retinal points are evaluated for their sensitivity to shorten the test duration and enhance patient focus. The location and the pattern of the points tested on the retina are decided by the different programs available on the machine. For example, 30-2, 24-2, 10-2, and the macular program are available on the Humphrey field analyzer.[15]

The 30-2 tests the central 30° field of the retina with fovea as fixation. This gives a round printout with 30° around the fovea (the field's radius is 30°). The digit 2 in this test denotes that the points are not located exactly on the vertical or horizontal midline (at the midline in the 30-1 test in the Humphrey field analyzer 1 machine). Instead, the points are equidistant from this line. This helps to better document the visual fields obeying the horizontal midline (glaucoma) and vertical midline (visual pathway lesions).

A total of 76 points are tested on the retina, each at a distance of 6° from the other in the 30-2 test. This leaves a bare area between the points. This bare area is a circle with a radius of 3° between any 4 points. This bare area remains unevaluated. The 24-2 test is a subset of 30-2 where the outermost points are eliminated, retaining 2 nasal points (specifically to look for nasal steps in glaucoma); this tests 54 points. This may be a better program for older adults as it reduces the time taken for the test. Also, this test reduces the number of false negatives due to the patient's fatigue, as the outer points are the last ones to be tested. Also, the points eliminated from the 30-2 field are not considered when diagnosing glaucoma. The distance between any 2 points remains 6°.

Because the distance between 2 points is 6°, paracentral scotomas can be missed on 24-2 or 30-2 programs. Therefore, any defect close to the fixation on these programs should be retested with the 10-2 program (see Image. Humphrey Visual Field Printout [10-2 Test]).[16] The 10-2 provides a higher resolution and highlights these defects.

A new program, 24-2c, has been recently introduced in the Humphrey field analyzer 3. Additional points have been added to the 24-2 program within the central 10° to be able to detect the paracentral scotomas. However, the resolution of 10-2 is not achieved.[17]

The 10-2 tests the central 10° of the retina, consisting of 68 closely placed points with a distance of 2° between any 2 points. This means that a circle with a radius of 1° is the area of the retina that remains unevaluated between any 4 points. Glaucoma hemifield analysis was not done during this program, and the visual field index was also not calculated. Thus, the number of points tested in various programs of the Humphrey visual field is:

- 68 points in 10-2

- 54 points in 24-2

- 76 points in 30-2

The Macular Program is the central 16 points of the 10-2 program. The points in the Macular Program are tested twice, and this is depicted as a second numeral in brackets below the points tested. The macular program and 10-2 strategy are used to check for split fixation in advanced glaucoma, which may be a predictor for snuff-out or loss of vision after trabeculectomy.[18]

Indications

Visual field testing is practical in various clinical scenarios, including:

- Diagnosis and progression of glaucoma

- Assessment of neurological conditions concerning the visual pathway

- Documentation of field defect and assessment of progression in retinal diseases like retinitis pigmentosa and inflammatory conditions like birdshot chorioretinopathy

- For the visual disability certificate or driver's license

- The legal definition of blindness

- Evaluation of unexplained vision loss

Normal and Critical Findings

Interpretation of Automated Perimetry

The automated perimetry report for Humphrey can be divided into eight zones for ease of understanding (see Image. Humphrey Visual Field Printout [24-2 Test] With Zones).

Zone 1: This section consists of the patient's information, including the patient's name, date of birth, visual acuity, pupil size, and the refractive correction used during the test.[19][20] The date of birth should be accurately entered; otherwise, the patient's data will be compared to the normative database of the wrong age group. The patient's pupil size should be at least 2.5 or 3 mm or the same as in the previous field test.[21][22][23] This also gives information about the test pattern performed (like 30-2 or 24-2), the strategy used (SITA standard or SITA Fast), and the fixation target used.

Using the recent most refractive correction of the patient with the appropriate near addition when performing the test is essential.[24] If possible, the refraction can be checked the same day before performing the perimetry. Using the built-in trial lens calculator to determine the appropriate trial lens power for the test is preferable, as the trial lens power often differs from the patient’s actual spectacle prescription.

Conditions requiring a complete near addition of 3 diopters include individuals aged 60 and older, pseudophakic or aphakic individuals, those with dilated pupils, and those with myopia of more than 3 diopters. A refractive error of even 1 diopter causes generalized depression in sensitivity, which may become a cause for misdiagnosis. The fixation target may be a central dot, the default target for the Humphrey visual field analyzer, or a large diamond below the central dot (see Image. Fixation Targets in Humphrey Field Analyzer). The larger diamond is used for patients with a large central scotoma. A small diamond fixation target within the large diamond is also used to evaluate the foveal threshold.

Zone 2: This zone mentions the foveal threshold and the reliability indices. The foveal threshold should correspond to the patient's visual acuity. A good visual acuity with a lower foveal threshold would indicate damage to the fovea, and a poor visual acuity with a higher foveal threshold would indicate a refractive error that has not been corrected before performing the test.

This zone also mentions reliability indices like fixation losses, false positives, and false negatives.[25] Fixation losses are calculated using the Heijl-Krakau method. The patient is supposed to maintain fixation at the fixation target throughout the test, which means that the location of the blind test should remain constant throughout the test.

After localizing the blind spot once in the test, the machine randomly presents a stimulus to that point later on during the test. Response to this stimulus would mean that the patient has moved the fixation, measured as fixation loss. The machine checks this multiple times during a test. The presence of more than 20% fixation losses indicates poor reliability of the field report, per the manufacturer. However, before looking at the fixation losses, the location of the blind spot should be confirmed on the printout.

The other 2 methods of fixation monitoring are gaze tracking and video monitoring of fixation. The gaze tracker is printed at the bottom of the report. The upward deflection denotes eye movement, and the downward graph tracing indicates a blink. This tracks the eye movement throughout the test, and the examiner can instruct the patient to re-fixate upon noticing this tracing. The video eye monitor displays the patient's eye on the machine's monitor; this is also a good tool for an observant examiner. The examiner can instruct the patient to focus on noticing any screen movement.

False positives are recorded when the patient responds without a presented stimulus. False positives up to 33% are acceptable, as per the manufacturer. Excess false positives mask the underlying visual field defects.[26] False negatives are recorded when the patient does not respond to a stimulus of higher intensity presented at the same location where previously the patient has responded to a lower-intensity stimulus. False negatives of more than 33% suggest poor reliability of the fields, per the manufacturer.[26][27]

Results from a study evaluating 10,262 visual fields noted that fixation losses did not meaningfully affect the reliability (difference between predicted and observed mean deviation) of perimetry in patients with suspected or manifest glaucoma who have been taking multiple field tests. The study's results also noted that false positives had the maximum impact on the reliability of the visual field at any level of false positives. Special precautions should be taken if false positives occur in advanced disease or are noted in more than 20% of catch trials.[28]

False negatives affect the reliability less than false positives. A value of more than 35% in advanced disease and more than 25% in early disease may significantly affect reliability. An increased duration of the test (more than 2 or 3 minutes) may also affect the reliability.[28]

Zone 3: The greyscale graph is a color-coded representation of the retinal sensitivity of the patient that is not used for the final interpretation of the field test but is essential for patient education. The values closer to 0 dB are illustrated as black points of varying shades, whereas points close to 50 dB are illustrated as white points. The points with sensitivity greater than 40 dB are seen as white scotomas on the greyscale and require careful interpretation. They usually indicate a "trigger-happy" patient who has responded without seeing the stimulus (false positive). The greyscale is useful when comparing a patient's fields during follow-up, as it indicates the progression of the visual field, both in extent and depth, over time at a glance, given that the reliability indices are within normal limits.

Zone 4: This zone comprises the total deviation numerical plot and total deviation probability plot.[29] The total deviation numerical plot indicates the depth of the field defect and compares the patient's dB value at all the retinal points tested to the normative data stored in the machine for that particular age. The normative database is calculated by collecting responses from healthy subjects. The upper 95% values are arbitrarily taken as normal, and the lower 5% are considered abnormal.

This comparison gives the amount of retinal sensitivity deviation from normal at each point tested. Zero on the total deviation numerical plot indicates no deviation from normal; a negative value indicates a decrease in retinal sensitivity, with higher negative values indicating worse retinal sensitivity. A numerical with no sign on the total deviation numerical plot indicates better retinal sensitivity. This data also calculates the mean and pattern standard deviation indexes.

Since the lower 5% of the data collected from the normal population is considered abnormal, all the abnormal data on the printout does not imply a disease state. The numerical values in the total deviation numerical plot are statistically analyzed and represented as a total deviation probability plot. The probability plot is color-coded, with lighter to darker shades representing P-values from less than 5% to those less than 0.5%. The probability plot demonstrates the extent or pattern of the field defect.

Zone 5: This zone comprises the pattern deviation numerical plot and the pattern deviation probability plot.[29][30] These demonstrate the presence of localized field defects and their pattern. To calculate the numerical values of the pattern deviation numerical plot, the values on the total numerical plot are chronologically arranged, and the seventh best point on this data is noted.

An amount in the range of this value is deducted from all the values on the total deviation numerical plot. This gives the pattern deviation plot corrected for generalized depression in retinal sensitivity, highlighting an underlying localized depression in the field. A generalized decrease in retinal sensitivity would mean a uniform decrease in the height of the hill of vision compared to the normative database. A localized defect or decrease in retinal sensitivity would mean an irregularity or localized depression in the hill of vision with a normal height of the remaining hill of vision. A combined localized with a generalized decrease in retinal sensitivity indicates a decrease in the height of the hill of vision and a localized depression.

Zone 6: This zone consists of the global indices, which are the mean deviation, pattern standard deviation, visual field index, and P-value.[31]

Mean Deviation: This is the average of all the values of the total deviation numerical plot; this usually has a negative value. Generalized field defects or advanced glaucoma will have a higher absolute mean deviation index. Localized field defects are, however, masked and have a low mean deviation index. A positive mean deviation index should be cautiously evaluated as that would mean a higher than normal retinal sensitivity. The false positives should be assessed in these cases.[31]

Pattern Standard Deviation: This indicates a deviation in the shape of the hill of vision and has a positive sign. A low value indicates a normal shape of the hill of vision, whereas a higher value indicates an irregular hill of vision. This is a useful index to diagnose cases with early glaucoma. In patients with advanced field defects, the shape of the hill of vision has deviated overall, so the pattern standard deviation value is low; hence, this indicator loses its value in patients with advanced field defects.[31] This index is known as the loss variance in the Octopus machine.

Short-Term Fluctuation: This is a feature of a field test using the full threshold strategy. Selective ten retinal points are checked for threshold twice, and the threshold value variability indicates a short-term fluctuation (SF). A value of more than 3 indicates low reliability.[31][32]

Corrected Pattern Standard Deviation: This is the pattern standard deviation value achieved after correcting for SF.

P-value: All the indices have a P-value that indicates the probability of that particular finding in a normal population. A P-value of less than 5% indicates a 5% or lesser chance for the index to be of that specific value in a normal population. No P-value in front of the index would mean a normal global index value.

Visual Field Index: This index is calculated from the pattern deviation numerical plot and was designed to indicate the amount of ganglion cell loss. The visual field index gives more weightage to the retinal points in the central field and indicates the percentage of retinal sensitivity of the patient compared to the normal retinal sensitivity for that age. A decrease in this index on follow-up perimetry scans indicates the progression of the field defect. Because it is derived from the pattern deviation graph values, cataract and refractive errors do not affect this index.[33]

Zone 7: This consists of the glaucoma hemifield test (GHT). Glaucoma affects the retinal ganglion cells on either side of the horizontal meridian.[34][35] Therefore, 5 areas, with a set of retinal points in each area, are tested on both sides of the horizontal meridian and compared. The results are displayed as GHT within normal limits, GHT borderline, or GHT outside normal limits.[36]

Zone 8: This is the raw data collected by the machine and consists of the retinal sensitivity (dB values) of each point tested for that program. A 0 dB value indicates absolute scotoma. In absolute scotoma, even the brightest stimulus is not perceived; in relative scotoma, a dimmer stimulus is not visible. After assessing the visual field printout, Anderson criteria help to diagnose and identify the field defects due to glaucoma.

Anderson and Patella Criteria (Also Called Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson Criteria)

Observe the following in the visual field printout on at least 2 fields:

- Abnormal GHT

- Three or more contiguous non-edge points in a location typical for glaucoma with a P-value of less than 5%, out of which at least 1 point has a P-value of less than 1%

- Corrected pattern standard deviation should be abnormal with a P-value of less than 5% [37]

All these findings should be reproducible in 2 successive 30-2 full threshold fields to classify a particular field defect to glaucoma. For the SITA strategy, modified Anderson criteria are applied where corrected pattern standard deviation is replaced with pattern standard deviation.

Interfering Factors

Interfering Factors

Stimulus Type: A white stimulus can be displayed on a white background. This is the most commonly used stimulus type.[38] A colored stimulus can be alternatively displayed on a white background.[39] A blue stimulus can be displayed on a yellow background (short-wavelength automated perimetry or SWAP) or a white background.[38][40] SWAP test stimulus targets a subset of retinal ganglion cells affected earlier in glaucoma, though this is debatable.[41] The role of SWAP in clinical settings needs further evaluation.[42]

Stimulus size: Five different sizes of stimulus can be used. The smallest stimulus size (0.0625 mm2 or 1/16 mm2) subtends an arc of 6 min, whereas the largest (64 mm2) subtends an arc of 1.7°. The most commonly used size is III.[43]

| Target | Size (mm2) | Degrees (°) |

| 0 | 1/16 | 6 minutes of arc |

| I | 1/4 | 0.1 |

| II | 1 | 0.2 |

| III | 4 | 0.43 |

| IV | 16 | 0.8 |

| V | 64 | 1.7 |

Stimulus Duration: The duration of stimulus conventionally used in the Humphrey field analyzer is 0.2 seconds.

Background Illumination: The uniform background illumination is 31.4 apostilb. At this luminance, the eye is minimally stimulated, and the stimulus's visibility depends on the contrast change rather than brightness.[44]

Ensuring a Good Visual Field Result

- The examiner conducting the test has a significant role to play. The patient should receive a careful explanation of what to do during the test.

- The examiner must carefully monitor the patient's gaze throughout the test.

- The examiner should take the perimetry test themself, as they can share their experience and help the patient better understand the test.

- The patient should be comfortably seated during the exam.

- The patient should understand what the stimulus will look like and how they need to respond.

- The results will be reliable if the patient is calm when taking the test and knows it can be paused whenever they want.

- The fields should never be interpreted in isolation. A structure-function correlation is always advised. The field defect on the printout should correlate with the changes in the optic nerve or retina.[45][46][45]

Clinical Significance

Automated perimetry is an indispensable tool for assessing the visual field. Analyzing visual field defects helps localize the disorders along the visual pathway. This analysis is also used in diagnosing and following individuals with glaucoma and other optic nerve and retinal conditions. Optic nerve pathologies like ischemic optic neuropathies, optic neuritis, and papilledema show characteristic field defects on visual field evaluation. Visual field examination is also useful in the assessment of legal blindness.

Results of Humphrey Field Analyzer in Various Clinical Scenarios

Field defects indicative of glaucoma (early-onset glaucoma to advanced disease) include (see Image. Types of Field Defects in Glaucoma):

- A nasal step respecting the horizontal meridian can indicate glaucoma.

- Paracentral scotoma or cluster of low sensitivity points 10° to 20° from the blind spot can also indicate glaucoma.

- A Seidel scotoma, where the paracentral scotoma reaches the blind spot, can indicate glaucoma.

- This Seidel scotoma extends in an arcuate shape to reach the horizontal meridian (arcuate defect).

- With the progression of the disease, a ring defect is formed when 2 arcuate scotomas are seen in the superior and inferior hemifields.[47]

- Advanced glaucomatous defects show a severe generalized defect with the sparing of a temporal island.[47][48][49]

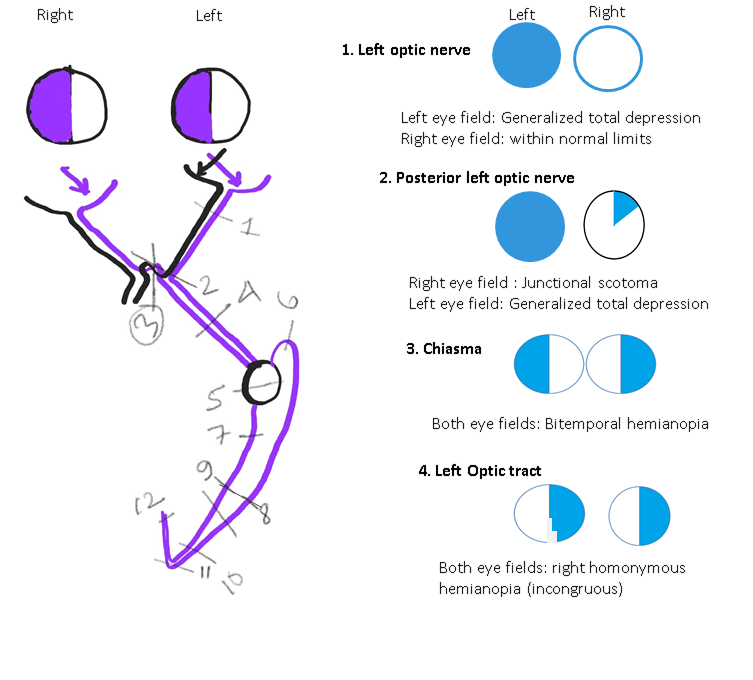

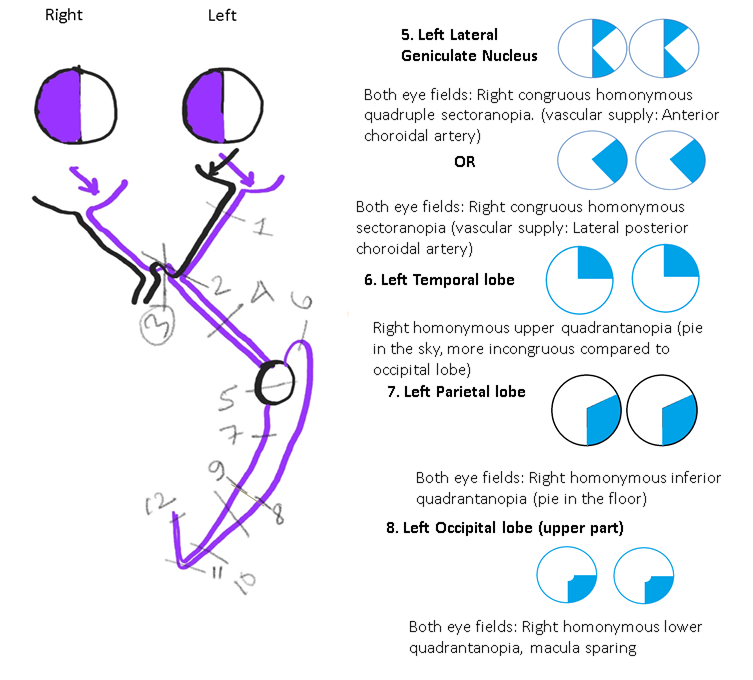

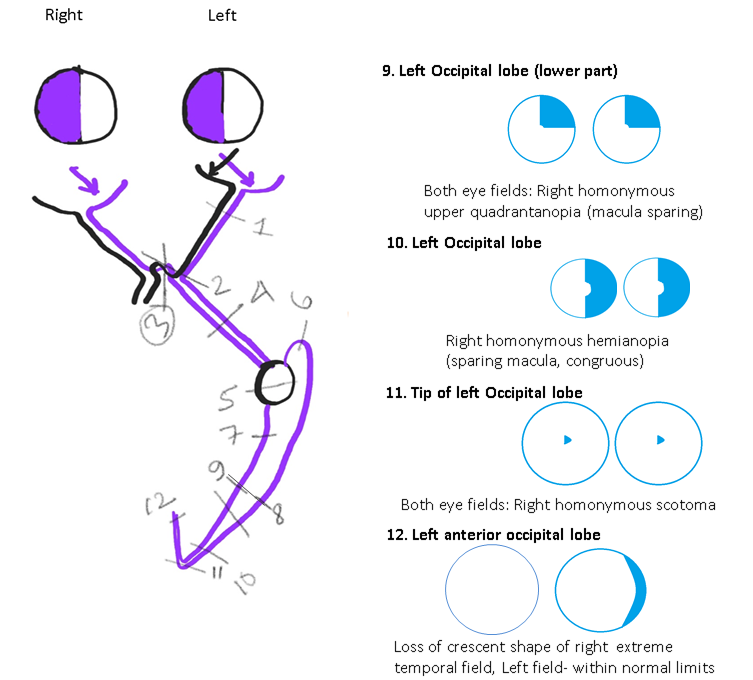

Other than glaucoma, perimetry can detect pathologies affecting the optic nerve pathway (see Images. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawings 1, 2, and 3]) and neuropathies.[50][51]

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: The field defects commonly found in these patients are enlargement of the blind spot, generalized constriction of the visual field, loss of inferonasal visual field, or nasal step.[52]

Papilledema: Enlargement of the blind spot is the most commonly seen visual field defect, with constriction of the visual field seen in late cases where optic atrophy has started.[49][53]

Optic Neuritis: The common field defect patterns documented in the optic neuritis treatment trial were diffuse field loss, altitudinal field defect, central scotoma or centrocecal scotoma, arcuate or double arcuate defects, and hemianopia defects (see Image. Types of Visual Field Defects in Other Diseases). Patients with hemianopia field defects were more likely to show demyelinating lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging.[54][55]

Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: Superior or inferior hemifield or altitudinal defects are the most common. Other field defect patterns include central scotoma, diffuse-field loss, or quadrantic field defects.[49][56][57]

Toxic Optic Neuropathy: Central scotomas are the commonly found field defect in cases of ethambutol optic neuropathy.[58] Toxic optic neuropathy has also been reported with vigabatrin, an anti-epileptic medication. Around 30% of patients taking vigabatrin show bilateral concentric peripheral visual field loss, and severe cases may have tunnel vision and visual loss that might progress even after stopping the drug.[59] The visual loss due to vigabatrin is usually irreversible.[60] Other substances causing toxic optic neuropathy include tobacco, methanol, isoniazid, ethylene glycol, vincristine, cisplatin, methotrexate, carboplatin, amiodarone, cimetidine, digitalis, toluene, cyclosporine, sulfonamides, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, linezolid, quinine, chloroquine, lithium, heavy metals (lead, mercury), lithium, and carbon monoxide.[58][61]

Disorders Involving Chiasma: Bitemporal hemianopia (see Image. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawing 1]) and junctional scotomas are common field defects that indicate optic chiasma lesions. Perimetry helps in the follow-up of the patients after surgery for pituitary gland tumors.[62]

Disorders Involving the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus: The lateral geniculate nucleus is situated in the posterior aspect of the thalamus and receives dual blood supply from the anterior choroidal artery (AChA, a branch of the internal carotid artery) and the lateral posterior choroidal artery (LPChA, a branch of the posterior cerebral artery).[63][64]

Depending on the artery involved, the field defect may be a wedge-shaped congruent homonymous sectoranopia (LPChA lesion), a quadruple sectoranopia, or loss of upper and lower homonymous quadrants (AChA lesion) (see Image. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawing 2]).

Disorders Involving the Optic Tract: Homonymous hemianopia (usually incongruous) is the typical field defect in these cases. Perimetry is useful in localizing the lesions along the visual pathway. Follow-up perimetry has been found to show improvement in 50% to 60% of these cases.[50][65][66]

Disorders Involving the Temporal Lobe: The damage of the Meyer loop causes a "pie in the sky" lesion (homonymous upper quadrantanopia) in the visual fields of both eyes (see Image. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawing 2]).[67]

Disorders Involving the Parietal Lobe: The damage of optic radiation traveling through the parietal lobe causes a "pie in the floor" lesion (homonymous lower quadrantanopia) in the visual fields of both eyes (see Image. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawing 2]).[67]

Disorders Involving the Occipital Lobe: The damage of the upper part of the occipital lobe causes congruous homonymous lower quadrantanopia (with macular sparing)(see Image. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawing 2]).[67] The damage of the lower part of the occipital lobe causes congruous homonymous upper quadrantanopia (macula-sparing). Damage to the occipital lobe causes contralateral congruous homonymous hemianopia. The tip of the occipital lobe, where the macula is represented, receives blood supply from both the middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery. This dual blood supply protects the macular vision even if one of these arteries is compromised.[68]

As a rule, posterior lesions cause more congruous (similar or identical) visual fields of both eyes than anterior lesions. However, this rule may not be strictly followed in a clinical setting.[65] Involvement of the tip of the occipital lobe can cause a homonymous central scotoma on the opposite side. Unilateral visual field loss can occur in anterior medial occipital cortex lesions. Such lesions cause unilateral temporal crescent-like peripheral visual field loss in the contralateral eye (the temporal crescent syndrome) (see Image. Neuroophthalmic Visual Field Defects [Schematic Drawing 3]).[69]

Optic Disc Drusen: Disc drusens do not cause visual symptoms; however, field defects are common—especially in individuals with superficially located or visible disc drusens. The field defects vary from inferonasal visual field defects, arcuate field defects, nasal steps, and enlargement of blind spots to constriction of visual fields.[70]

Tilted Optic Disc: This is a congenital anomaly where the optic nerve makes an angled entry into the eye, resulting in inferior tilt, more commonly inferonasal ectasia or crescent, which causes a myopic refractive error. Perimetry of these individuals shows a superotemporal field defect similar to that found in chiasmal disorders. However, unlike chiasmal disorders, field defects are due to the tilted disc crossing the vertical midline, as these defects are caused by the refractive error induced by the tilt.[71][72]

Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis: Lesions within one disc diameter of the optic nerve head are known to involve all the layers of the retina. Visual field testing of such lesions after healing has shown absolute scotomas with breakout to the periphery, probably because of the involvement of photoreceptors and the nerve fiber layers. Visual field testing in these cases will help test the treatment efficiency of such cases.[73]

Malingering: Individuals who feign visual loss for personal gain may present with complaints of tunnel vision or constriction of the visual field. This can be differentiated from constriction of the visual field due to organic causes by testing their field by kinetic Goldmann perimetry. In the case of malingerers, the degree of peripheral constriction of the visual field will remain the same even after increasing the distance between the individual and the tangent screen. Individuals with an organic cause for the peripheral constriction will have a lesser extent of peripheral constriction when their distance from the tangent screen is increased. Another way of differentiating functional visual loss from organic causes is that the constriction of the visual field will be the same for stimuli of different sizes or contrasts.[74]

Individuals may also claim to have monocular hemianopias. These can be differentiated from organic causes by performing binocular visual field testing on the Goldmann perimeter. The monocular hemianopia is compensated by the overlapping visual field of the normal eye in the case of individuals with organic causes.[75]

Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion: The field loss is segmental, corresponding to the area drained by the occluded vein. Kinetic perimetry can better document the peripheral field loss, as automated perimetry documents the field loss up to 30°.[76] However, test strategies for evaluating larger areas of the visual field are also available in the Humphrey field analyzer, which includes the full threshold strategy for the 60-4 program.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Both central and peripheral scotoma are more common in patients with ischemic central retinal vein occlusion than in non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion. The common peripheral field defect seen with ischemic central retinal vein occlusion is an inferonasal defect.[77]

Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion: The field defect varies with the duration of onset of the disease. Patients presenting within 1 week of onset may have central scotoma or central altitudinal defects corresponding to the area of affection. Peripheral field defects commonly found are inferior nasal or superior nasal field defects.[78]

Retinitis Pigmentosa: The field defect characteristic of this disease is gradually progressive peripheral field loss. The superior visual field is often involved first due to the early involvement of the inferior retina.[79] The central visual field is affected in patients with cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membrane, or retinal pigment epithelium changes at the macula.[80][81]

Birdshot Chorioretinopathy: Constriction of the peripheral visual field, enlargement of blind spot, central or paracentral scotoma, or generalized diminished sensitivity are common visual field defects associated with birdshot chorioretinopathy.[82][83]

Migraine: Patients with migraine may present with visual field defects. The prevalence of field defects is known to increase with the individual's age and the disease's duration.[84] The types of field defects associated with migraine include generalized depression of sensitivity, arcuate defects, nasal step, and isolated scotomas.[84][85] Typically, scintillating scotomas with zig-zag outer boundaries are seen, the size of which may increase (fortification).[86]

Riddoch Phenomena: This is also known as statokinetic dissociation.[87] In this phenomenon, an individual can perceive moving objects in the affected visual field. However, the individual fails to perceive static objects or stimuli in the affected visual field. In other words, the static perimetry of such an individual will show homonymous hemianopia or quadrantanopia, whereas the kinetic perimetry will be within normal limits. This is usually present in conditions where the primary visual cortex located in the occipital lobe is affected.[87]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Types of Visual Field Defects in Other Diseases. The common field defect patterns documented in the optic neuritis treatment trial were diffuse field loss, altitudinal field defect, central scotoma or centrocecal scotoma, arcuate or double arcuate defects, and hemianopia defects.

Contributed by S Ruia, MS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

. Automated perimetry. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 1996 Jul:103(7):1144-51 [PubMed PMID: 8684807]

Johnson CA, Wall M, Thompson HS. A history of perimetry and visual field testing. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2011 Jan:88(1):E8-15. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182004c3b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21131878]

Hayreh SS. Pathogenesis of visual field defects. Role of the ciliary circulation. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1970 May:54(5):289-311 [PubMed PMID: 4987892]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeijl A, Asman P. Pitfalls of automated perimetry in glaucoma diagnosis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 1995 Apr:6(2):46-51 [PubMed PMID: 10150857]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBebie H, Fankhauser F, Spahr J. Static perimetry: strategies. Acta ophthalmologica. 1976 Jul:54(3):325-38 [PubMed PMID: 988949]

Grzybowski A, Aydin P. Edme Mariotte (1620-1684): Pioneer of Neurophysiology. Survey of ophthalmology. 2007 Jul-Aug:52(4):443-51 [PubMed PMID: 17574069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThomas R, George R. Interpreting automated perimetry. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2001 Jun:49(2):125-40 [PubMed PMID: 15884520]

Dehaene S. The neural basis of the Weber-Fechner law: a logarithmic mental number line. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2003 Apr:7(4):145-147 [PubMed PMID: 12691758]

Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Balestrery FG. Suprathreshold static perimetry in glaucoma and other optic nerve disease. Ophthalmology. 1979 Jul:86(7):1278-86 [PubMed PMID: 233860]

Heijl A. Automatic perimetry in glaucoma visual field screening. A clinical study. Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. Albrecht von Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology. 1976 Jul 26:200(1):21-37 [PubMed PMID: 786063]

Artes PH, Iwase A, Ohno Y, Kitazawa Y, Chauhan BC. Properties of perimetric threshold estimates from Full Threshold, SITA Standard, and SITA Fast strategies. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2002 Aug:43(8):2654-9 [PubMed PMID: 12147599]

Wu Z, Medeiros FA. Recent developments in visual field testing for glaucoma. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2018 Mar:29(2):141-146. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000461. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29256895]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBengtsson B, Olsson J, Heijl A, Rootzén H. A new generation of algorithms for computerized threshold perimetry, SITA. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1997 Aug:75(4):368-75 [PubMed PMID: 9374242]

Bengtsson B, Heijl A. SITA Fast, a new rapid perimetric threshold test. Description of methods and evaluation in patients with manifest and suspect glaucoma. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1998 Aug:76(4):431-7 [PubMed PMID: 9716329]

Bosworth CF, Sample PA, Johnson CA, Weinreb RN. Current practice with standard automated perimetry. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2000 Dec:15(4):172-81 [PubMed PMID: 17585432]

De Moraes CG, Hood DC, Thenappan A, Girkin CA, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN, Zangwill LM, Liebmann JM. 24-2 Visual Fields Miss Central Defects Shown on 10-2 Tests in Glaucoma Suspects, Ocular Hypertensives, and Early Glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2017 Oct:124(10):1449-1456. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.04.021. Epub 2017 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 28551166]

Yamane MLM, Odel JG. Introducing the 24-2C Visual Field Test in Neuro-Ophthalmology. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. 2021 Dec 1:41(4):e606-e611. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001157. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33417411]

Law SK, Nguyen AM, Coleman AL, Caprioli J. Severe loss of central vision in patients with advanced glaucoma undergoing trabeculectomy. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2007 Aug:125(8):1044-50 [PubMed PMID: 17698750]

Weinreb RN, Perlman JP. The effect of refractive correction on automated perimetric thresholds. American journal of ophthalmology. 1986 Jun 15:101(6):706-9 [PubMed PMID: 3717255]

Koller G, Haas A, Zulauf M, Koerner F, Mojon D. Influence of refractive correction on peripheral visual field in static perimetry. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2001 Oct:239(10):759-62 [PubMed PMID: 11760037]

Lindenmuth KA, Skuta GL, Rabbani R, Musch DC, Bergstrom TJ. Effects of pupillary dilation on automated perimetry in normal patients. Ophthalmology. 1990 Mar:97(3):367-70 [PubMed PMID: 2336275]

Rebolleda G, Muñoz FJ, Fernández Victorio JM, Pellicer T, del Castillo JM. Effects of pupillary dilation on automated perimetry in glaucoma patients receiving pilocarpine. Ophthalmology. 1992 Mar:99(3):418-23 [PubMed PMID: 1565454]

Lindenmuth KA, Skuta GL, Rabbani R, Musch DC. Effects of pupillary constriction on automated perimetry in normal eyes. Ophthalmology. 1989 Sep:96(9):1298-301 [PubMed PMID: 2779997]

Gaffney M. Refractive errors and automated perimetry: discussion and case studies. Journal of ophthalmic nursing & technology. 1993 Jul-Aug:12(4):167-71 [PubMed PMID: 8301674]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee M, Zulauf M, Caprioli J. The influence of patient reliability on visual field outcome. American journal of ophthalmology. 1994 Jun 15:117(6):756-61 [PubMed PMID: 8198159]

Vingrys AJ, Demirel S. False-response monitoring during automated perimetry. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 1998 Jul:75(7):513-7 [PubMed PMID: 9703040]

Gordon MO, Kass MA. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: design and baseline description of the participants. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1999 May:117(5):573-83 [PubMed PMID: 10326953]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYohannan J, Wang J, Brown J, Chauhan BC, Boland MV, Friedman DS, Ramulu PY. Evidence-based Criteria for Assessment of Visual Field Reliability. Ophthalmology. 2017 Nov:124(11):1612-1620. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.04.035. Epub 2017 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 28676280]

Heijl A, Lindgren G, Olsson J, Asman P. Visual field interpretation with empiric probability maps. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1989 Feb:107(2):204-8 [PubMed PMID: 2916973]

Bengtsson B, Lindgren A, Heijl A, Lindgren G, Asman P, Patella M. Perimetric probability maps to separate change caused by glaucoma from that caused by cataract. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1997 Apr:75(2):184-8 [PubMed PMID: 9197570]

Mills RP. Statistical aids to visual field interpretation. Journal of ocular pharmacology. 1991 Spring:7(1):89-95 [PubMed PMID: 2061694]

Flammer J, Drance SM, Augustiny L, Funkhouser A. Quantification of glaucomatous visual field defects with automated perimetry. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1985 Feb:26(2):176-81 [PubMed PMID: 3972500]

Bengtsson B, Heijl A. A visual field index for calculation of glaucoma rate of progression. American journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Feb:145(2):343-53 [PubMed PMID: 18078852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSommer A, Duggan C, Auer C, Abbey H. Analytic approaches to the interpretation of automated threshold perimetric data for the diagnosis of early glaucoma. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1985:83():250-67 [PubMed PMID: 3832529]

Hart WM Jr, Becker B. The onset and evolution of glaucomatous visual field defects. Ophthalmology. 1982 Mar:89(3):268-79 [PubMed PMID: 7088510]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAsman P, Heijl A. Glaucoma Hemifield Test. Automated visual field evaluation. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1992 Jun:110(6):812-9 [PubMed PMID: 1596230]

Chakravarti T. Assessing Precision of Hodapp-Parrish-Anderson Criteria for Staging Early Glaucomatous Damage in an Ocular Hypertension Cohort: A Retrospective Study. Asia-Pacific journal of ophthalmology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2017 Jan-Feb:6(1):21-27. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000201. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28161915]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSoliman MA, de Jong LA, Ismaeil AA, van den Berg TJ, de Smet MD. Standard achromatic perimetry, short wavelength automated perimetry, and frequency doubling technology for detection of glaucoma damage. Ophthalmology. 2002 Mar:109(3):444-54 [PubMed PMID: 11874745]

Sample PA, Johnson CA, Haegerstrom-Portnoy G, Adams AJ. Optimum parameters for short-wavelength automated perimetry. Journal of glaucoma. 1996 Dec:5(6):375-83 [PubMed PMID: 8946293]

Johnson CA, Adams AJ, Casson EJ, Brandt JD. Blue-on-yellow perimetry can predict the development of glaucomatous visual field loss. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1993 May:111(5):645-50 [PubMed PMID: 8489447]

Havvas I, Papaconstantinou D, Moschos MM, Theodossiadis PG, Andreanos V, Ekatomatis P, Vergados I, Andreanos D. Comparison of SWAP and SAP on the point of glaucoma conversion. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2013:7():1805-10. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S50231. Epub 2013 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 24092960]

van der Schoot J, Reus NJ, Colen TP, Lemij HG. The ability of short-wavelength automated perimetry to predict conversion to glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010 Jan:117(1):30-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.046. Epub 2009 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 19896194]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChoplin NT, Sherwood MB, Spaeth GL. The effect of stimulus size on the measured threshold values in automated perimetry. Ophthalmology. 1990 Mar:97(3):371-4 [PubMed PMID: 2336276]

Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Balestrery FG. Static and acuity profile perimetry at various adaptation levels. Documenta ophthalmologica. Advances in ophthalmology. 1981 Mar 20:50(2):371-88 [PubMed PMID: 7227177]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeijl A, Lindgren G, Olsson J. The effect of perimetric experience in normal subjects. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1989 Jan:107(1):81-6 [PubMed PMID: 2642703]

Johnson CA, Adams CW, Lewis RA. Fatigue effects in automated perimetry. Applied optics. 1988 Mar 15:27(6):1030-7. doi: 10.1364/AO.27.001030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20531515]

POSNER A, SCHLOSSMAN A. Development of changes in visual fields associated with glaucoma. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1929). 1948 May:39(5):623-39 [PubMed PMID: 18122923]

Gramer E, Gerlach R, Krieglstein GK, Leydhecker W. [Topography of early glaucomatous visual field defects in computerized perimetry]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1982 Jun:180(6):515-23 [PubMed PMID: 7132176]

Quigley HA, Addicks EM, Green WR. Optic nerve damage in human glaucoma. III. Quantitative correlation of nerve fiber loss and visual field defect in glaucoma, ischemic neuropathy, papilledema, and toxic neuropathy. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1982 Jan:100(1):135-46 [PubMed PMID: 7055464]

Kedar S, Ghate D, Corbett JJ. Visual fields in neuro-ophthalmology. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Mar-Apr:59(2):103-9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.77013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21350279]

Szatmáry G, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Can Swedish interactive thresholding algorithm fast perimetry be used as an alternative to goldmann perimetry in neuro-ophthalmic practice? Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2002 Sep:120(9):1162-73 [PubMed PMID: 12215089]

Wall M, George D. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Incidence and defects related to visual field strategy. Archives of neurology. 1987 Feb:44(2):170-5 [PubMed PMID: 3813933]

Grehn F, Knorr-Held S, Kommerell G. Glaucomatouslike visual field defects in chronic papilledema. Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. Albrecht von Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology. 1981:217(2):99-109 [PubMed PMID: 6912773]

Wall M, Johnson CA, Kutzko KE, Nguyen R, Brito C, Keltner JL. Long- and short-term variability of automated perimetry results in patients with optic neuritis and healthy subjects. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1998 Jan:116(1):53-61 [PubMed PMID: 9445208]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKeltner JL, Johnson CA, Spurr JO, Beck RW. Visual field profile of optic neuritis. One-year follow-up in the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1994 Jul:112(7):946-53 [PubMed PMID: 8031275]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWall M, Punke SG, Stickney TL, Brito CF, Withrow KR, Kardon RH. SITA standard in optic neuropathies and hemianopias: a comparison with full threshold testing. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2001 Feb:42(2):528-37 [PubMed PMID: 11157893]

Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Visual field abnormalities in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: their pattern and prevalence at initial examination. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2005 Nov:123(11):1554-62 [PubMed PMID: 16286618]

Kahana LM. Toxic ocular effects of ethambutol. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 1987 Aug 1:137(3):213-6 [PubMed PMID: 3607664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLawden MC, Eke T, Degg C, Harding GF, Wild JM. Visual field defects associated with vigabatrin therapy. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1999 Dec:67(6):716-22 [PubMed PMID: 10567485]

Krauss GL. Evaluating risks for vigabatrin treatment. Epilepsy currents. 2009 Sep-Oct:9(5):125-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2009.01315.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19826501]

Radhakrishnan DM, Samanta R, Manchanda R, Kumari S, Shree R, Kumar N. Toxic Optic Neuropathy: A Rare but Serious Side Effect of Chloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2020 May-Jun:23(3):413-415. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_339_19. Epub 2020 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 32606561]

Huber A. [Chiasmal syndromes (author's transl)]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1977 Feb:170(2):266-78 [PubMed PMID: 853669]

Luco C, Hoppe A, Schweitzer M, Vicuña X, Fantin A. Visual field defects in vascular lesions of the lateral geniculate body. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1992 Jan:55(1):12-5 [PubMed PMID: 1548490]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCovington BP, Al Khalili Y. Neuroanatomy, Nucleus Lateral Geniculate. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082181]

Kedar S, Zhang X, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Congruency in homonymous hemianopia. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 May:143(5):772-80 [PubMed PMID: 17362865]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhang X, Kedar S, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Natural history of homonymous hemianopia. Neurology. 2006 Mar 28:66(6):901-5 [PubMed PMID: 16567709]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRuia S, Tripathy K. Humphrey Visual Field. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36256759]

Rehman A, Al Khalili Y. Neuroanatomy, Occipital Lobe. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31335040]

Ali K. The temporal crescent syndrome. Practical neurology. 2015 Feb:15(1):53-5. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2014-001014. Epub 2014 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 25416654]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePalmer E, Gale J, Crowston JG, Wells AP. Optic Nerve Head Drusen: An Update. Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press). 2018 Dec:42(6):367-384. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2018.1444060. Epub 2018 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 30524490]

Vuori ML, Mäntyjärvi M. Tilted disc syndrome may mimic false visual field deterioration. Acta ophthalmologica. 2008 Sep:86(6):622-5 [PubMed PMID: 18162059]

Phu J, Wang H, Miao S, Zhou L, Khuu SK, Kalloniatis M. Neutralizing Peripheral Refraction Eliminates Refractive Scotomata in Tilted Disc Syndrome. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2018 Oct:95(10):959-970. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001286. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30247238]

Stanford MR, Tomlin EA, Comyn O, Holland K, Pavesio C. The visual field in toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Jul:89(7):812-4 [PubMed PMID: 15965156]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBruce BB, Newman NJ. Functional visual loss. Neurologic clinics. 2010 Aug:28(3):789-802. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2010.03.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20638000]

Smith CH, Beck RW, Mills RP. Functional disease in neuro-ophthalmology. Neurologic clinics. 1983 Nov:1(4):955-71 [PubMed PMID: 6390158]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Branch retinal vein occlusion: natural history of visual outcome. JAMA ophthalmology. 2014 Jan:132(1):13-22. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24158729]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman MB. Natural history of visual outcome in central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2011 Jan:118(1):119-133.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.04.019. Epub 2010 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 20723991]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman MB. Branch retinal artery occlusion: natural history of visual outcome. Ophthalmology. 2009 Jun:116(6):1188-94.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.01.015. Epub 2009 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 19376586]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBerson EL, Sandberg MA, Rosner B, Birch DG, Hanson AH. Natural course of retinitis pigmentosa over a three-year interval. American journal of ophthalmology. 1985 Mar 15:99(3):240-51 [PubMed PMID: 3976802]

Fishman GA, Maggiano JM, Fishman M. Foveal lesions seen in retinitis pigmentosa. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1977 Nov:95(11):1993-6 [PubMed PMID: 921578]

Tripathy K. Cystoid Macular Edema in Retinitis Pigmentosa with Intermediate Uveitis Responded Well to Oral and Posterior Subtenon Steroid. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2018:33(4):492-493. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2017.1303521. Epub 2017 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 28353369]

Gordon LK, Monnet D, Holland GN, Brézin AP, Yu F, Levinson RD. Longitudinal cohort study of patients with birdshot chorioretinopathy. IV. Visual field results at baseline. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Dec:144(6):829-837 [PubMed PMID: 17937923]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePriem HA, Oosterhuis JA. Birdshot chorioretinopathy: clinical characteristics and evolution. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1988 Sep:72(9):646-59 [PubMed PMID: 2460128]

Lewis RA, Vijayan N, Watson C, Keltner J, Johnson CA. Visual field loss in migraine. Ophthalmology. 1989 Mar:96(3):321-6 [PubMed PMID: 2710523]

Comoğlu S, Yarangümeli A, Köz OG, Elhan AH, Kural G. Glaucomatous visual field defects in patients with migraine. Journal of neurology. 2003 Feb:250(2):201-6 [PubMed PMID: 12574951]

Dahlem MA, Müller SC. Migraine aura dynamics after reverse retinotopic mapping of weak excitation waves in the primary visual cortex. Biological cybernetics. 2003 Jun:88(6):419-24 [PubMed PMID: 12789490]

Hayashi R, Yamaguchi S, Narimatsu T, Miyata H, Katsumata Y, Mimura M. Statokinetic Dissociation (Riddoch Phenomenon) in a Patient with Homonymous Hemianopsia as the First Sign of Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Case reports in neurology. 2017 Sep-Dec:9(3):256-260. doi: 10.1159/000481304. Epub 2017 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 29422846]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence