Introduction

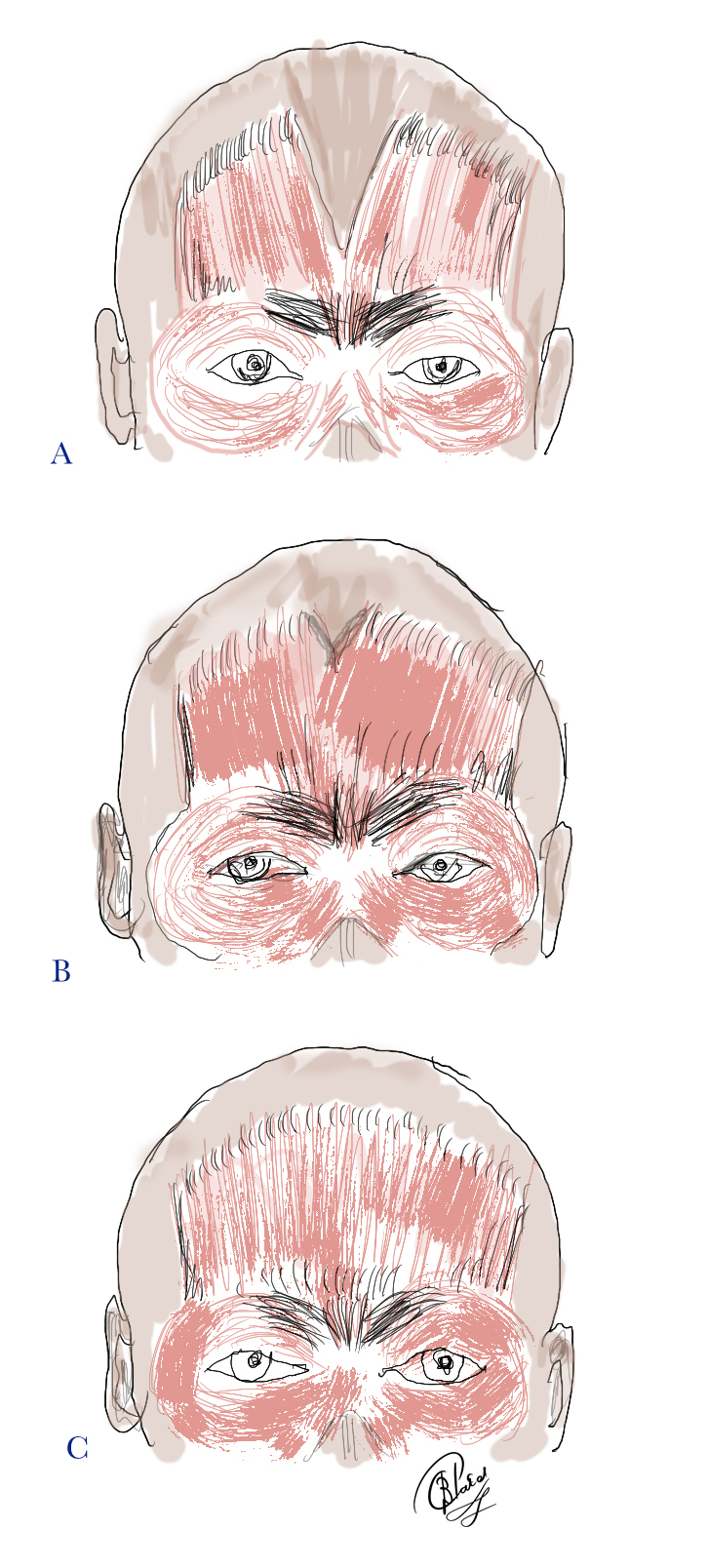

The frontalis muscle plays a significant role in our day-to-day social interactions. As the only muscle that raises the eyebrows, its function goes beyond simply keeping the brows out of one’s visual field; it is also necessary for conveying emotions and nonverbal communication. The antagonist muscles to the frontalis muscle are the procerus muscle, the corrugator supercilii muscle, and the orbicularis oculi muscle. (Fig 1) The frontalis, corrugator, procerus, and orbicularis muscles all have cutaneous insertions and have a confluence at the glabella, and the orbital rim, where their respective movements and forces extended to the skin may cause cutaneous rhytids (frown lines, smile lines, forehead lines, horizontal nasal lines). The balance between these muscles determines the eyebrow position and shape.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The frontalis muscle is on the front of the head, and while it may seem to behave as an independent muscle, it is actually part of a larger structure referred to as the occipitofrontalis muscle or epicranius.[1] A helpful tool for remembering the layers of the scalp is the acronym SCALP:

S: Skin

C: subCutaneous connective tissue

A: Aponeurosis (galea)

L: Loose areolar connective tissue

P: Periosteum

The occipitofrontalis is composed of two muscle bellies: frontalis and occipitalis, which are attached and encased by dense connective tissue called the epicranial aponeurosis or galea aponeurotica. The occipital part of the occipitofrontalis muscle moves the scalp forwards, and the frontalis part lifts the brows and moves the anterior scalp backward. When the frontalis muscle contracts, the vertical fibers pull the skin of the eyebrows upward.

The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) continues above the zygomatic arch and includes the temporoparietal fascia (as it blends into the galea) and the frontalis muscle as part of the SMAS.

The antagonist muscles to the frontalis muscle are the orbicularis oculi, corrugated, and procerus muscles. The frontalis muscle has no bony attachments. The corrugator muscle is below the frontalis and the orbicularis muscles and has a bony origin from the medial orbital rim.

Surface Anatomy

Frontalis muscle action produces horizontal forehead lines. Four types of forehead lines have been described [2]:

- Full, straight lines that run across the whole forehead (45%)

- Gull wing-shaped lines with a central depression and lateral elevation (30%)

- Short central horizontal lines over the middle of the forehead but few or no lines laterally (10%)

- Lateral straight lines as two columns formed on the lateral aspect of the forehead with no central lines (15%)

Embryology

Like the other muscles involved in facial expression, the frontalis muscle originates from the second pharyngeal arch, which forms between the third and eighth weeks of development.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The frontalis muscle receives its blood supply from branches of both the internal and external carotid arteries. The supratrochlear and supraorbital arteries supply the muscle from the inferior margin after they exit the orbit and travel up the forehead. The supraorbital artery can exit from the supraorbital notch/foramen, while the supratrochlear artery exits more medially from the orbit. They are both branches of the ophthalmic artery, which is a branch of the internal carotid artery. Soon after their respective exits, the supratrochlear and supraorbital arteries separate further into both superficial and deep branches.[4][5] The superficial arteries supply the muscle, galea, and skin, while the deeper layer supplies the periosteum. The supratrochlear and supraorbital arteries supply a bulk of the blood medially, and the frontal branch, which comes off of the superficial temporal artery, supplies the muscle more laterally. The arteries form an anastomosis with one another to form a highly vascularized network.

The lymphatic drainage of the forehead is complicated and not well understood. Studies looking at the drainage have found that the more lateral portion of the forehead most likely drains differently than the medial portion.[6] Regardless, it appears the forehead drains mainly into the preauricular nodes and parotid nodes.[6][7]

The main venous drainage occurs between three veins: the supratrochlear vein being most medial, then the intermediate supraorbital vein, and finally, the lateral frontal vein. The three further connect through a transverse vein that runs superior to the orbit, appropriately named the transverse supraorbital vein [8]. The transverse supraorbital vein connects medially to the angular vein, which eventually drains into the ophthalmic vein and cavernous sinus. It is important to remember this relationship when considering the risk of external facial infections leading to potentially harmful intracranial infections or cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Nerves

The muscles of facial expression receive nerve supply from cranial nerve VII (the facial nerve), which separates into five main branches: temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. The facial nerve exits the skull at the stylomastoid foramen and its temporal branch crosses over the zygomatic arch, passes through the areolar tissue on the surface of the temporal fascia, and subsequently enters into the frontalis muscle to provide its deep innervation. Three branches of the temporal nerve, the anterior, middle, and posterior, are responsible for innervating the orbicularis oculi, frontalis, and the corrugator muscles.[9] The temporal (also called the frontal) branch of the facial nerve runs within the superficial layer of the temporoparietal fascia, with the temporal artery just anterior to the nerve. The temporal branch enters the frontalis muscle into its deeper part. Injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve is avoided by either dissecting subcutaneously or just anterior to the superficial part of the deep temporal fascia (the glistening layer in front of the temporalis muscle).

The supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves that run along their respective arteries, penetrate through the frontalis in order to reach the superficial skin. These are branches of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve and do not directly innervate the muscle, but instead innervate the overlying skin. The medial branches of the supraorbital nerve are superficial and the lateral branches are deep.

Muscles

The frontalis muscle is made up of vertical striations in a fan-like distribution. Clinically, the muscle is sometimes divided into medial, intermediate and lateral fibers, although no anatomical or histological distinctions exist. It originates posteriorly from the galea aponeurotica, which corresponds with the hairline on the surface. Inferomedially, the muscle interdigitates with fibers of procerus muscle, while more inferolaterally, it has attachments to the orbicularis oculi and corrugator muscles. Generally, the frontalis inserts at the eyebrow dermis and terminates laterally at the temporal ridge, but there is some variance and occasionally may terminate more medially as well.[10][11] While overall, it is a thin muscle with high vascularity, the bulk of it is located right above the brow. It is thinnest laterally, which represents an area of weakness and the first area to sag as we age.

- The lateral-most extent of the frontalis muscle where it interdigitates with the orbital orbicularis muscle varies: when measured from the supraorbital notch, it may be small, medium, or large. (Fig 2) The exact distribution in the normal population is unknown. However, the lateral brow will have less support from the frontalis in subjects that have a smaller horizontal frontalis muscle, thereby causing more significant brow ptosis and lateral brow ptosis with secondary dermatochalasis in particular

- The lateral-most extent of the frontalis muscle where it interdigitates with the orbital orbicularis muscle may be asymmetric in 20%. This arrangement may explain asymmetric lateral brow ptosis and secondary dermatochalasis. Research has found similar variations in the length of the corrugator muscle as being short or long, although it revealed no differences in the procerus or orbicularis muscles.[12]

- Research has found the right belly of the frontalis muscle to be significantly larger than the left side, although electromyographic studies have shown the right and left frontalis muscles generate the same amount of muscle activity.[13]

- The frontalis muscle may be confluent from right to left with no bifurcation (up to 45% of subjects).[2] The rest will demonstrate a variable central bifurcation between the frontalis muscles. (Fig 3) This bifurcation consists of connective tissue continuous with the galea aponeurotica, and with variable width from person to person. Abramo et al. showed that in 15% of anatomical dissections, there was complete separation of the frontalis muscle bellies with a central galeal aponeurosis.[2]

- Gross asymmetry between the right and left frontalis muscle belly may be found in a third of subjects.[1]

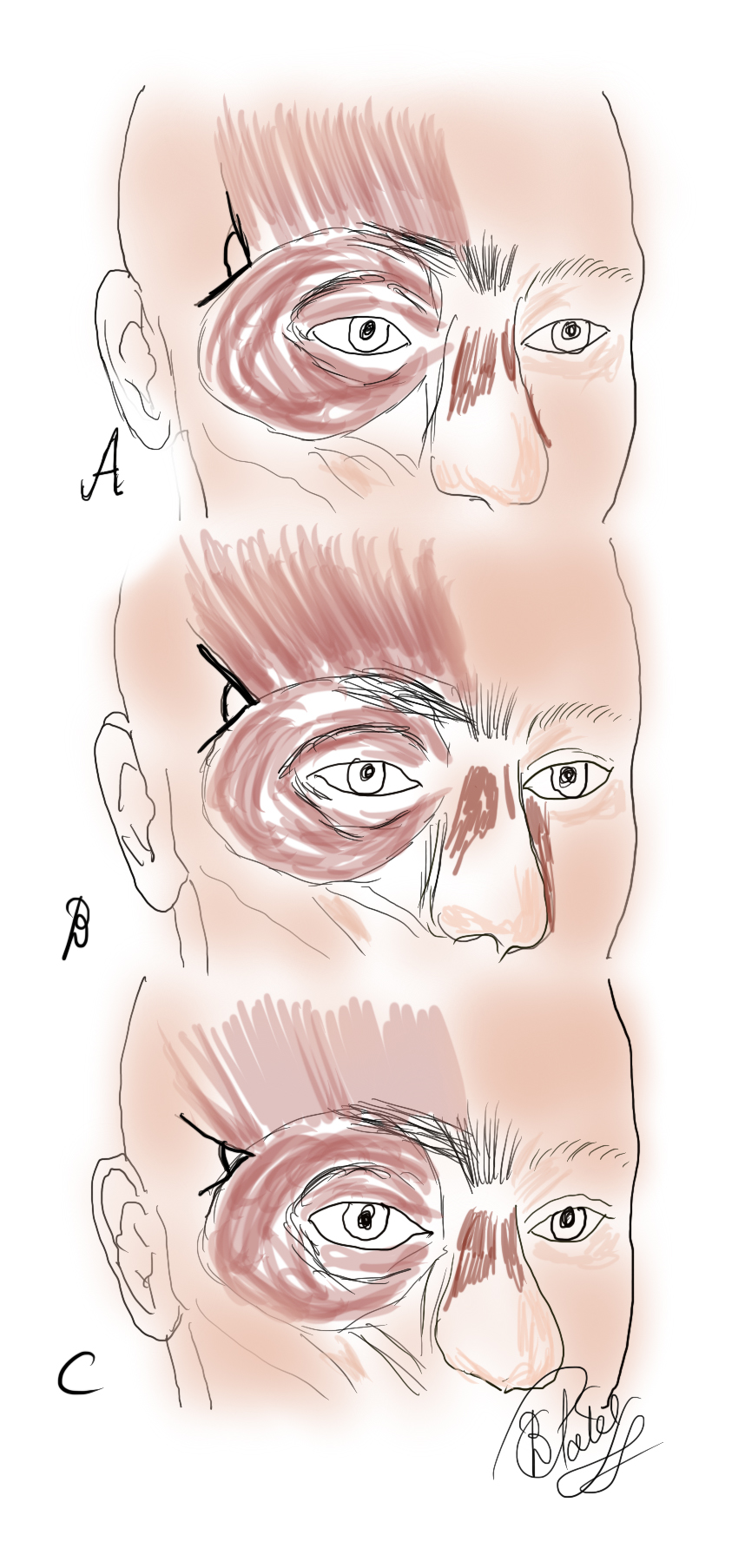

- The angle between where the frontalis interdigitates with the orbital orbicularis muscle (the frontalis-orbicularis angle) may be small, medium, and large, and there is evidence that it may become smaller with age, thereby causing further lateral brow ptosis and secondary dermatochalasis. (Fig 4)

- The lateral edge of the frontalis muscle may extend to the linea temporalis (temporal ridge or crest), or may extend beyond it or may fall short of it.

Surgical Considerations

An understanding of frontalis anatomy is essential for reconstructive and cosmetic procedures. In cases where children are born with an absent or dysfunctional levator palpebrae superioris, such as in bilateral congenital ptosis, the ptosis can be so substantial that it leads to vision obstruction and amblyopia. In those patients, frontalis-orbicularis muscle advancement is possible. This procedure, first described over 100 years ago, now involves making an incision at the crease of the upper eyelid, followed by vertical incisions into the frontalis muscle. Finally, the muscle flap is advanced inferiorly to form a connection with the orbicularis oculi muscle.[14] Another option for ptosis correction utilizing the frontalis is referred to as a frontalis sling or frontalis suspension. This procedure is often favored over a muscle flap advancement and involves a similar approach, except that it uses a suture to connect the frontalis to the tarsal plate.[15] Similar to the flap, this offers the necessary pull to elevate the eyelid with frontalis contraction. Ptosis can be secondary to mechanical, neurological, traumatic, and muscular dysfunctions, for all of which surgery can be the potential last line of defense.[16]

Clinical Significance

Improvement of forehead skin:

The forehead is a site that many people seek to rejuvenate to maintain a youthful appearance. Relaxed skin tension lines, also called wrinkles, form perpendicular to the underlying muscles and as we age. A trial of nonsurgical options is often the first step to try and alleviate lines, vascular changes, and skin pigment changes. Nonsurgical options can include creams, peels, abrasives, and lasers.[17]

Use of botulinum toxin for forehead and frown lines:

The importance of anatomy plays a role when dealing with minimally invasive procedures like botulinum injections. Botulinum toxin is an effective tool for treating rhytides and wrinkles and can be injected directly into the frontalis muscle. The decreased muscular contraction leads to a decrease in rhytid production and a more youthful appearance. This procedure involves multiple injections into the frontalis. The aim is to avoid complete paralysis of the frontalis muscle: 10 to 20 units of botox distributed across the forehead yields satisfactory relaxation of the horizontal rhytids. When injecting the frontalis, the corrugator and procerus muscles should also be injected. A safe zone for frontalis muscle injections is 2 cm above the brow. If done improperly, the toxin can spread to the levator palpebrae superioris and lead to nonpermanent ptosis. Also, it is important to maintain the balance between the depressors of the brow and the levators. A weak frontalis muscle and dominant set of depressors would cause the brow to descend. Also, improper distribution of botulinum into the medial frontalis can lead to a "Spock" deformity, in which the lateral portion of frontalis is capable of contraction, but the medial portion is relaxed. The other area of frontalis action, especially in women that often goes undertreated is where the frontalis is close to the anterior hairline, which results in prominent residual high horizontal rhytids.

Fillers for grooves at the glabella:

Fillers are also often placed into the forehead to create volume and fullness in the horizontal wrinkles at the root of the nose (caused by the procerus muscle) and the verticle "elevenses" at the medial end of each brow, caused by the corrugator muscles. Knowing the underlying anatomy, including the depth and location of the various muscles, is essential for avoiding devastating complications during injections. For example, too much filler or misplaced filler when targeting the glabella (the region between the eyebrows and above the nose) can lead to a retinal artery occlusion and blindness.[4] An inappropriate injection into an artery, for example, the supratrochlear, could lead to acute necrosis of the tissue. Fillers are never injected with force or in boluses. Another approach we have found to be safe is to pinch the skin upwards with small amounts of filler injected gently.

Upper and lower motor neuron facial palsy:

Understanding the nerve supply to the forehead is also essential when evaluating a patient with a potential stroke. Middle cerebral artery strokes can cause contralateral facial paralysis, but these strokes often spare the forehead. This presentation is because the lower motor neurons responsible for innervating the top half of the face receive input from both hemispheres, while the lower half does not. If the injury is at the level of the lower motor neuron, as seen with Bell palsy, then we see a complete hemifacial paralysis.

Tissue expansion:

Tissue expansion is needed when repairing large forehead or nasal defects. Whereas in the neck, expanders are placed in front of the platysma, in the forehead, it is crucial to place expanders under the frontalis muscles, with insertion via incisions made within the hairline.

Other Issues

Key Learning Points:

- The frontalis muscle is actually part of the occipitofrontalis muscle, which is two muscle bellies connected by the galea aponeurotic.

- Part of the venous drainage from the forehead enters the cavernous sinus.

- The frontalis muscle is responsible for elevating the eyebrows, while the corrugator supercilii, orbicularis oculi, and procerus play a role in its depression.

- The function of the forehead is often spared in middle cerebral artery strokes.

- To avoid injury to the sensory and motor nerves to the frontalis muscle, dissection planes should be subcutaneous, subperiosteal or subgaleal.

- The medial branches of the supraorbital nerve are superficial, and the lateral branches are deep.

- The variations in the horizontal extent of the frontalis muscle must be appreciated as these variations may have a bearing on the extent of brow ptosis.

- The surface and applied anatomy of the forehead and the extent of the frontalis muscle must be appreciated when performing surgery in this region or injecting toxins. (Fig 5)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Frontalis Muscle. The angle of insertion of the frontalis muscle laterally as measured against the orbital orbicularis oculi varies A. Large B. Intermediate C. Small It is thought that with aging, the angle becomes smaller with less lateral support to the brow, thereby contributing to lateral brow ptosis

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Frontalis Muscle: Anatomy of the forehead 1. Frontalis muscle 2. Brow fat pad 3. Orbital orbicularis oculi 4. Lateral orbital orbicularis (responsible for descent of the lateral brow) 5. Depressor supercilii 6. Corrugator supercilii 7. Supratrochlear nerve 8. Supraorbital nerve at supraorbital notch 9. Medial branch of the supraorbital nerve 10. Lateral branch of the supraorbital nerve 11. Temporal fusion line (temporal crest or linea temporalis) 12. Conjoint "tendon" 13. Frontal branch of the facial nerve Contributed by Prof. Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Costin BR, Plesec TP, Sakolsatayadorn N, Rubinstein TJ, McBride JM, Perry JD. Anatomy and histology of the frontalis muscle. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 Jan-Feb:31(1):66-72. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000244. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25417794]

Abramo AC, Do Amaral TP, Lessio BP, De Lima GA. Anatomy of Forehead, Glabellar, Nasal and Orbital Muscles, and Their Correlation with Distinctive Patterns of Skin Lines on the Upper Third of the Face: Reviewing Concepts. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2016 Dec:40(6):962-971 [PubMed PMID: 27743084]

Ansari A, Bordoni B. Embryology, Face. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424786]

Beer JI, Sieber DA, Scheuer JF 3rd, Greco TM. Three-dimensional Facial Anatomy: Structure and Function as It Relates to Injectable Neuromodulators and Soft Tissue Fillers. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2016 Dec:4(12 Suppl Anatomy and Safety in Cosmetic Medicine: Cosmetic Bootcamp):e1175. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001175. Epub 2016 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 28018776]

Fukuta K, Potparic Z, Sugihara T, Rachmiel A, Forté RA, Jackson IT. A cadaver investigation of the blood supply of the galeal frontalis flap. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1994 Nov:94(6):794-800 [PubMed PMID: 7972424]

Wiener M, Uren RF, Thompson JF. Lymphatic drainage patterns from primary cutaneous tumours of the forehead: refining the recommendations for selective neck dissection. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2014 Aug:67(8):1038-44. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.04.017. Epub 2014 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 24927861]

Koroulakis A, Jamal Z, Agarwal M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Lymph Nodes. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020689]

Yoshioka N, Rhoton AL Jr. Vascular anatomy of the anteriorly based pericranial flap. Neurosurgery. 2005 Jul:57(1 Suppl):11-6; discussion 11-6 [PubMed PMID: 15987565]

Poblete T, Jiang X, Komune N, Matsushima K, Rhoton AL Jr. Preservation of the nerves to the frontalis muscle during pterional craniotomy. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Jun:122(6):1274-82. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS142061. Epub 2015 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 25839922]

Knize DM. An anatomically based study of the mechanism of eyebrow ptosis. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1996 Jun:97(7):1321-33 [PubMed PMID: 8643714]

Costin BR, Wyszynski PJ, Rubinstein TJ, Choudhary MM, Chundury RV, McBride JM, Levine MR, Perry JD. Frontalis Muscle Asymmetry and Lateral Landmarks. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2016 Jan-Feb:32(1):65-8. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000577. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26505231]

Abramo AC. Anatomy of the forehead muscles: the basis for the videoendoscopic approach in forehead rhytidoplasty. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1995 Jun:95(7):1170-7 [PubMed PMID: 7761503]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrach JS, VanSwearingen J. Measuring fatigue related to facial muscle function. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1995 Oct:76(10):905-8 [PubMed PMID: 7487428]

Cruz AAV, Akaishi APMS. Frontalis-Orbicularis Muscle Advancement for Correction of Upper Eyelid Ptosis: A Systematic Literature Review. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Nov/Dec:34(6):510-515. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001145. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29958196]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRosenberg JB, Andersen J, Barmettler A. Types of materials for frontalis sling surgery for congenital ptosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019 Apr 23:4(4):CD012725. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012725.pub2. Epub 2019 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 31013353]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKoka K, Patel BC. Ptosis Correction. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969650]

Arnaoutakis D, Bassichis B. Surgical and Nonsurgical Techniques in Forehead Rejuvenation. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2018 Oct:34(5):466-473. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1669990. Epub 2018 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 30296798]