Introduction

Conjunctivitis is a common cause of eye redness and, subsequently, a common complaint in the emergency department, urgent care clinics, and primary care clinics. People of any age, demographic, or socioeconomic status can be affected. More than 80% of all acute cases are generally diagnosed by non-ophthalmologists, such as internists, primary care providers, pediatricians, and nurse practitioners.[1] In the United States, this imparts a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system, costing about $857 million annually.[2] While conjunctivitis is typically a temporary condition that does not often lead to vision loss, ruling out other potential sight-threatening causes of red-eye during evaluation is crucial.

The conjunctiva is the transparent, lubricating mucous membrane covering the eye’s outer surface and comprises 2 parts: the bulbar conjunctiva that covers the globe and the tarsal conjunctiva that lines the eyelid’s inner surface.[3]

Conjunctivitis refers to the inflammation of the conjunctival tissue, engorgement of the blood vessels, pain, and ocular discharge, and is classified as acute or chronic and infectious or noninfectious. Acute conjunctivitis refers to a symptom duration of 3 to 4 weeks from presentation, usually only lasting 1 to 2 weeks, whereas chronic is defined as lasting more than 4 weeks.

Apart from being caused by various infective agents, conjunctivitis may also be associated with some systemic illnesses, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, nutritional deprivation (especially vitamin A deficiency), congenital metabolic syndromes, such as porphyria and Richner-Hanhart syndrome and immune-related disorders, such as Reiter syndrome.[4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Eye redness and discharge are often caused by conjunctivitis, which can be infectious or noninfectious. Viral conjunctivitis is the most frequent cause, followed by bacterial conjunctivitis. Allergic and toxin-induced conjunctivitis are the most common noninfectious causes.

Infectious conjunctivitis can result from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. However, 80% of acute cases of conjunctivitis are viral—the most common pathogen being adenovirus. Adenoviruses are responsible for 65% to 90% of cases of viral conjunctivitis.[6] Other common viral pathogens are herpes simplex, herpes zoster, and enterovirus.

Bacterial conjunctivitis is far more common in children than adults, and the pathogens responsible for bacterial conjunctivitis vary depending on the affected child’s age group. Staphylococcal species, specifically Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenza, are the most common bacterial causes in adults.[7] However, the disease is more often caused by Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis in children.[6] Other bacterial causes include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Corynebacterium diphtheria. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the most common cause of bacterial conjunctivitis in neonates and sexually active adults.[8]

Allergens, toxins, and local irritants are responsible for noninfectious conjunctivitis.

Acute Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Bacterial conjunctivitis is a common condition, usually self-limiting and caused by direct contact with infected secretions. The most common organisms are Staphylococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenza, and Moraxella catarrhalis. A few cases are caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae that invade the intact corneal epithelium. Meningococcal conjunctivitis can also occur in children but is rare.[9]

Giant Fornix Syndrome

Giant fornix syndrome is identified by chronic and recurring pseudomembranous conjunctivitis accompanied by a discharge of pus. This condition arises due to the accumulation of debris in the upper tarsal conjunctiva and fornix, which serves as a breeding ground for persistent bacterial colonization. Typically, this syndrome affects older adults and is linked to levator disinsertion. One can observe a significant amount of protein clumps in the upper fornix, which may require double eversion of the lid for visibility. Additionally, cases of giant fornix syndrome can be accompanied by superficial corneal vascularization and lacrimal obstruction; this infection can also occur in one eye only. The treatment usually involves sweeping the fornix with a cotton tip applicator, topical and systemic antibiotics, and topical steroids in required cases. In nonrevolving cases, reconstruction of the fornix is mandatory.[10]

Chlamydial Conjunctivitis

Chlamydia trachomatis is present in 2 forms: the elementary body and the reticular body. Serovars D-K causes chlamydial inclusion conjunctivitis and affects both the eyes and genitals. It is a common infection among sexually active young individuals, with a 5% to 20% prevalence. The infection can spread through genital secretions and has an incubation period of 1 week. Symptoms of the disease include redness, watering, and discharge from one or both eyes. In chronic cases, the infection can last several months, leading to watery or mucopurulent discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, follicles in the inferior fornix, and possibly the upper tarsal conjunctiva. After 2 to 3 weeks, superficial punctate keratitis and perilimbal superficial infiltrates can be seen. Follicles and papillae development are prominent in chronic cases, and conjunctival scarring and corneal pannus may occur.[11]

Trachoma

Trachomatous conjunctivitis may seem straightforward initially, but if recurring infections happen, this can cause long-lasting immune reactions. These reactions involve a cell-mediated immune response called type 4 hypersensitivity, which can result in vision loss and intermittent chlamydial antigen. While prior exposure can provide short-term immunity, reinfection can result in severe complications.[12] Trachomatous conjunctivitis consists of 2 stages: the active inflammatory and chronic cicatricial stages, which can overlap. The active stage is characterized by mixed follicular and papillary conjunctivitis and mucopurulent discharge. In children less than 2 years, papillary components can predominate. The cicatricial stage is common in the middle-aged. Linear conjunctival scarring is seen in mild cases, and broad scars (Arlt line) are seen in severe cases. The clinical signs are common in upper tarsal conjunctiva. Superior limbal follicles may resolve and cause a row of shallow depressions called Herbert pits. Other symptoms include trichiasis, distichiasis, corneal vascularization, cicatricial entropion, corneal opacification, and dry eye disease.[13]

Neonatal Conjunctivitis

Neonatal conjunctivitis, also known as ophthalmia neonatorum, is inflammation of the conjunctiva occurring within the first month of life and can be observed in up to 10% of neonatal patients. Conjunctivitis is potentially severe as this condition is transferred to the infant from the mother during delivery and differs from adult conjunctivitis because this includes ocular and systemic involvement.[14] The common organisms that cause neonatal conjunctivitis are Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2), Staphylococcus sp, Haemophilus influenza, and other gram-negative organisms. Topical agents may also cause conjunctivitis, known as chemical conjunctivitis. The causative agent of infection can be determined based on symptoms. Staphylococcal infection can cause sticky eyes, while HSV2 infection may lead to watery discharge and vesicular lesions. Chlamydia can result in mucopurulent dismissal and pseudomembranes, while bacteria can cause purulent discharge. Finally, gonococcal infection may lead to hyperpurulent discharge and eyelid edema.[14]

Viral Conjunctivitis

Nonspecific Acute Follicular Conjunctivitis

This is a common form of viral conjunctivitis, usually due to adenoviral infection with various serologic variants. This type of conjunctivitis is less common than other forms of adenoviral conjunctivitis. The patient’s ophthalmic complaints include watering, redness, irritation, itching, and mild photophobia. Patients may also have a sore throat and common cold as prime complaints.[15] If only 1 eye is initially affected, the other eye will become symptomatic 1 to 2 days later.

Pharyngoconjunctival Fever

This is mainly caused by adenovirus serovars 3, 4, and 7 and can spread by droplets within families with upper respiratory tract infections. Keratitis is seen in 30% of patients but is rarely severe. Sore throat is usually severe in these patients.[16]

Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis

This is caused by Serovars 8, 19, and 37 and is the most severe form of adenoviral infection. Keratitis is a common feature and is found in 80% of patients, with photophobia as the primary complaint.[17]

Acute Hemorrhagic Conjunctivitis

This can be due to enteroviruses or coxsackievirus, though other causative microorganisms can be seen. This conjunctivitis is usually seen in tropical areas and typically lasts 1 to 2 weeks. Conjunctival hemorrhage is generally marked.[18]

Chronic Adenoviral Conjunctivitis

This causes nonspecific follicular or papillary reactions that persist over the years. The condition is rare and self-limiting.[15]

Herpes Simplex Virus

The herpes simplex virus causes follicular conjunctivitis and is typically the result of a primary infection often accompanied by skin vesicles.[19]

Systemic Viral Infections

Varicella, measles, and mumps can cause follicular conjunctivitis, which is common in childhood. Varicella zoster virus causes conjunctivitis associated with shingles. Human immunodeficiency virus can also cause conjunctivitis.[20]

Molluscum Contagiosum

This causes skin infection and occurs in children between 2 and 4 years, and transmission is usually through contact and autoinoculation. Chronic follicular conjunctivitis can be seen and is secondary to skin lesion-shedding viral particles. Ocular discharge and irritation can occur; further, molluscum lesions can be present surrounding eyelashes.[21]

Acute Allergic Conjunctivitis

In this condition, the acute conjunctival reaction is secondary to allergens such as pollen. The common symptoms are itching, watering, and chemosis in younger children. This condition is commonly seen in young children playing outdoors in summer or spring. Treatment is generally unnecessary, and the conjunctival swelling reduces within hours due to reduced vascular permeability. Cold compresses and adrenaline application help to reduce chemosis.[22]

Seasonal Allergic Conjunctivitis

Also known as hay fever eyes, seasonal allergic conjunctivitis is more common during summer and spring. The most frequently associated allergens are grass, pollen, and trees—although the allergens can differ based on location.[22]

Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis

In this conjunctivitis, the symptoms are seen throughout the year, though generally worse in autumn. Exposure to house mites, animal dander, and fungal allergens is most likely to cause this type of conjunctivitis, which is less common and tends to be milder than seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.[23]

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a condition affecting both eyes and tends to recur. A combination of immunoglobulin E and cell-mediated immune mechanisms causes this conjunctivitis. VKC is most commonly observed in boys over 5 years old. By the time they reach their late teens, about 95% of patients experience remission. The remaining group may develop atopic keratoconjunctivitis. VKC is often associated with eczema and asthma and typically peaks in late spring and summer. This particular medical condition causes an increase in eosinophils. Symptoms include itching, tearing, sensitivity to light, feeling like there’s something in the eye, burning, and discharge. There are 3 main types: limbal, papillary, and mixed. In the early stages, the conjunctiva appears red, with velvety hypertrophy on the superior tarsal. Macropapillae, which can progress to giant papillae, are also seen. Mucus deposits can form between these giant papillae. Peri-limbal Horner–Trantas dots are focal white dots of degenerated epithelial cells and eosinophils indicative of VKC.[24]

Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis

This condition is rare and affects both eyes, typically appearing in adults between 30 and 50 years with no gender preference. However, in about 5% of cases, atopic keratoconjunctivitis begins in childhood. Patients with this condition often have a history of eczema and asthma and are sensitive to many airborne substances. Further, this conjunctivitis can occur throughout the year but is more common during winter. Compared to VKC, this condition has fewer eosinophils present. Patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis may experience significant changes in the skin on their eyelids, including redness, dryness, scaling, thickening, and excoriation. Pruritis is also common. Patients may also experience staphylococcal blepharitis with madarosis. One common symptom is the absence of the lateral portion of the eyebrows, known as the Hertoghe sign. Additionally, patients may have lid folds secondary to persistent itching, known as Dennie-Morgan folds. Patients may also experience tight facial skin and ptosis. The conjunctival involvement is usually located on the lower eyelid, while VKC affects the upper eyelid. Patients may experience watery discharge along with stringy mucoid secretions. Other symptoms may include hyperemia, micropapillae, macropapillae, diffuse conjunctival infiltration, scarring, symblepharon formation, fornical shortening, and keratinization of the caruncle. Limbal involvement, Horner-Trantas spots, shield ulceration, superficial vascularization, and punctate erosions may also be seen. Patients may also develop keratoconus, cataracts, retinal detachment, and an increased risk of bacterial, fungal, and herpes simplex keratitis.[25]

Non-Allergic Eosinophilic Conjunctivitis

This chronic non-atopic condition is predominantly seen in middle-aged women with dry eyes. The common symptoms are itching, redness, foreign body sensations, and mild watery discharge.[26]

Contact Allergic Blepharoconjunctivitis

This is an acute or subacute T cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity reaction triggered by certain eye drops and mascara ingredients that ophthalmologists and optometrists frequently observe. The reaction commonly appears in the conjunctiva, but signs can also be visible on the eyelid skin, including redness, thickening, irritation, and sometimes fissuring. Treatment involves removing the substance that caused the reaction and applying mild topical steroids.[27]

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis

Mechanically induced papillary conjunctivitis, or giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC), is caused by various mechanical stimuli to the tarsal conjunctiva. This condition can occur due to contact lens wear, leading to proteins and cellular debris deposition on the contact lens surface. GPC can also be caused by ocular prostheses, exposed sutures, scleral buckles, corneal surface irregularity, and filtering blebs. In addition, chronic papillary conjunctivitis may be present in patients with mucus fishing syndrome.[28]

Factitious Conjunctivitis

This form of conjunctivitis is typically caused intentionally but can also happen accidentally, as with mucus fishing syndrome or when removing contact lenses. Factitious conjunctivitis can be caused by trauma or the mechanical introduction of irritants like soaps. In some cases, overuse of prescribed medications may also be a factor. Symptoms may include redness in the lower part of the eye and staining of the conjunctiva with rose bengal. There may also be linear abrasions on the cornea, persistent corneal defects, or, in rare cases, corneal perforation.[29]

Ligneous Conjunctivitis

This is a rare form of chronic pseudomembranous conjunctivitis associated with membranous pathological changes and is identified by recurring, wood-like, fibrin-rich pseudo membranes on both sides of the tarsal conjunctiva. Conjunctivitis can occur due to minor injuries and systemic events such as fever and antifibrinolytics therapy. Patients with this condition experience a lack of plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis. In addition to affecting the eyes, this condition can damage the periodontal tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, kidneys, middle ear, and genital area. Lung problems can be fatal.[30]

Parinaud Oculoglandular Syndrome

This rare oculoglandular syndrome is characterized by a low-grade fever and unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis with associated follicles and regional preauricular lymphadenopathy. The symptoms mimic cat scratch disease caused by Bartonella henselae.[31]

Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis

This type of chronic conjunctivitis affects the superior limbus, superior bulbar, and tarsal conjunctiva, can occur in one or both eyes and is more common in middle-aged women with hyperthyroidism. About 50% of women have abnormal thyroid function, and 3% develop thyroid eye disease with superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis.[32] This condition is often misdiagnosed, its course can be lengthy, and remission can happen without intervention. The causes of this condition include papillary conjunctivitis, contact lens-induced papillary conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis from trauma or surgery, blink-related trauma between the upper and superior bulbar conjunctiva, tear film insufficiency, and lax conjunctival tissue. Conjunctival inflammation can cause edema and redundancy, and mechanical damage to the tarsal and bulbar conjunctival surface can occur due to excessive conjunctival movement. This condition looks similar to conjunctivochalasis, which affects the bulbar conjunctiva.[33]

Conjunctivitis in Blistering Disorders

Mucus Membrane Pemphigoid

Mucus membrane pemphigoid, also known as cicatricial pemphigoid, is a long-lasting condition that causes blisters on the skin and mucous membranes. This autoimmune disorder triggers an immune response called type 2 cytotoxic hypersensitivity. This response causes antibodies to bind to the basement membrane zone, which activates the complement cascade and recruits inflammatory cells. This action can lead to symptoms such as papillary conjunctivitis, diffuse hyperemia, edema, and subtle fibrosis. The exact cause of this condition is unknown.[34] In severe cases, subconjunctival fibrosis, inferior fornical shortening, symblepharon formation, and necrosis may occur. The plica is flattened, and the caruncle is keratinized. Also, dry eye disease can occur due to the occlusion of goblet cells, accessory lacrimal glands, and main lacrimal ductules. Other findings include trichiasis lashes, blepharitis, and lid margin keratinization.[35]

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and erythema multiforme major are terms used interchangeably to refer to the same condition. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, Lyell syndrome, is a more severe form of SJS. While this condition is commonly observed in younger adults, it can also affect older individuals. SJS is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction caused by drug exposure, including antibiotics, sulphonamides, trimethoprim, paracetamol, cold compresses, and anticonvulsants. Mycoplasma pneumoniae may also be a contributing factor. In the acute stage, redness, severe pain, grittiness, watering, and blurred vision are common ocular features. Other signs include crusting of lid margins, skin lesions, papillary conjunctivitis, conjunctival membranes, pseudo membranes, hyperemia, hemorrhages, blisters, and patchy scar formation. Additional clinical features that may occur include keratopathy, iritis, panophthalmitis (occasionally), conjunctival cicatrization, and keratopathy.[36]

Epidemiology

The occurrence of conjunctivitis depends on various factors such as age, gender, and time of the year. In the emergency department, cases of acute conjunctivitis show a bimodal distribution. The first peak is observed among children under 7, with the highest incidence between 0 and 4 years. The second peak occurs at 22 years in women and 28 years in men. Though overall rates of conjunctivitis diagnosed in the emergency department are slightly higher in women than in men, seasonality also plays a role in the presentation and diagnosis of conjunctivitis. Across all age groups, there is a peak incidence of conjunctivitis in children 0 to 4 years in March, followed by other age groups in May.

Regardless of changes in climate or weather patterns, seasonality is consistent for all geographic regions, as described in a nationwide emergency department study. Allergic conjunctivitis is the most common cause of conjunctivitis, affecting 15% to 40% of the population, and is often observed in spring and summer. Bacterial conjunctivitis rates are highest from December to April.[3][6][37] Allergic conjunctivitis is considered the most common allergic ocular disease, affecting 15% to 20% of the population, with seasonal and perennial types.[38]

Pathophysiology

Conjunctivitis occurs when the conjunctiva becomes inflamed due to an infection or an irritant. As a result of this inflammation, the blood vessels in the conjunctiva dilate, causing redness or hyperemia, and the conjunctiva can also become swollen. The inflammation affects the entire conjunctiva, and depending on the cause, discharge may also be present. Bacterial conjunctivitis occurs when the eye's surface tissues are colonized by normal flora like Staphylococci sp., Streptococci, and Corynebacteria. The epithelial covering of the conjunctiva is the primary defense mechanism against infection, and any disruption in this barrier can lead to infection.[39] Secondary defense mechanisms include immune reactions carried out by the tear film immunoglobulins and lysozyme, conjunctival vasculature, and the rinsing action of blinking and lacrimation.

History and Physical

When diagnosing conjunctivitis, conducting a comprehensive history and physical examination is essential to identify the underlying cause and determine the appropriate treatment. When gathering the patient’s ocular history, note the timing of onset, any preceding symptoms, whether one or both eyes are affected, accompanying symptoms, past treatments and outcomes, previous occurrences, type of discharge, presence of pain or itching, eyelid characteristics, periorbital involvement, changes in vision, sensitivity to light, and corneal opacity.

The ocular exam should focus on visual acuity, extraocular motility, visual fields, discharge type, shape, size and response of pupil, the presence of proptosis, corneal opacity, foreign body assessment, tonometry, and eyelid swelling.

In cases of conjunctivitis, the redness typically affects the entire surface of the conjunctiva, including both the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva. This visible redness helps to rule out more severe conditions like keratitis, iritis, and angle-closure glaucoma, which only affect the bulbar conjunctiva and spare the tarsal conjunctiva. If the redness is only in one specific area, it may be a sign of a foreign body, pterygium, or episcleritis, and an alternative diagnosis should be considered.[40]

When identifying the cause of conjunctivitis, the type of discharge is a crucial factor. Bacterial conjunctivitis is usually linked to either purulent discharge, which forms again after being removed from the eye, or mucopurulent discharge, which is thicker and adheres to the eyelashes.[41][42] Compared to other causes of bacterial conjunctivitis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae has a hyperacute presentation, consisting of copious purulent discharge, sudden onset, and rapid progression. In both viral and allergic conjunctivitis, the discharge is typically watery. Associated preauricular lymphadenopathy indicates viral conjunctivitis rather than allergic conjunctivitis.[6]

Determining the cause of conjunctivitis can be challenging as its symptoms are not specific. For instance, itching is usually linked to allergic conjunctivitis, especially when accompanied by watery discharge and a history of atopy. However, results from a study found that 58% of patients with bacterial conjunctivitis (confirmed through culture testing) also reported itchy eyes.[43]

Similarly, the presence of papillae is a nonspecific finding in conjunctivitis. Papillae are small elevations with central vessels, usually under the superior tarsal conjunctiva. They can be present in both noninfectious and infectious conjunctivitis. Papillae are often present in bacterial conjunctivitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and contact lens intolerance. The papillae in chronic allergic conjunctivitis can lead to a cobblestone appearance of the conjunctiva.

While also nonspecific, the presence of follicles, in correlation with other findings, can help differentiate the etiology of conjunctivitis. Follicles are small, elevated yellow-white lesions found at the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva junction, also known as the lower cul-de-sac. Follicles are a lymphocytic response often present in chlamydial and adenoviral conjunctivitis.

In a patient with a history of perioral fever blisters, current vesicular skin lesions, or suspected viral conjunctivitis, a fluorescein examination should be performed as herpes simplex virus (HSV) can produce corneal dendritic lesions, even in the absence of skin lesions. This exam is an essential step in the physical evaluation, as it may result in the only finding to differentiate HSV from other causes of viral conjunctivitis, which subsequently requires different management and follow-up. In comparison, herpes zoster ophthalmicus typically presents in patients over 60 with a painful vesicular rash following the distribution of the fifth cranial nerve. Prodrome can include headache, fever, malaise, and photophobia. Vesicles at the tip of the nose, Hutchinson sign, strongly predict eye involvement with herpes zoster.[44]

While conjunctivitis often presents similarly, a thorough systematic history and physical exam can safely rule out any acute sight-threatening diagnoses and elucidate the likely cause of conjunctivitis. The classic findings of the 3 most common types of conjunctivitis are:

- Bacterial - Findings include conjunctival redness, having the sensation of a foreign body in the eye, morning matting of the eyes, white-yellow purulent or mucopurulent discharge, conjunctival papillae, and infrequently preauricular lymphadenopathy.[45]

- Viral - Findings include eye itching, watery discharge, tearing, a history of recent upper respiratory tract infection, inferior palpebral conjunctival follicles, and tender preauricular lymphadenopathy.[46][47]

- Allergic: Findings include eye itching and burning, watery discharge, history of allergies/atopy, edematous eyelids, conjunctival papillae, and no preauricular lymphadenopathy.[48]

Evaluation

Labs and cultures are rarely indicated to confirm conjunctivitis diagnosis. Eyelid cultures and cytology are usually reserved for recurrent conjunctivitis, those resistant to treatment, suspected gonococcal or chlamydial infection, suspected infectious neonatal conjunctivitis, and adults presenting with severe purulent discharge.[3][6][46] Rapid antigen testing is available for adenoviruses and can be used to confirm suspected viral causes of conjunctivitis to prevent unnecessary antibiotic use. One study comparing rapid antigen testing to polymerase chain reaction, viral culture, and confirmatory immunofluorescent staining found rapid antigen testing to have a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of up to 94%.[49]

Imaging studies generally do not play an important role in the workup of conjunctivitis unless an underlying pathology is suspected. For instance, magnetic resonance angiography, computed tomography (CT) scan, and orbital Doppler may play a role in the case of a cavernous sinus fistula. In addition, an orbital CT scan may help rule out an orbital abscess when conjunctivitis coexists with orbital cellulitis.

Specific procedures may be required to address the underlying cause of conjunctivitis. Trichiasis may require the removal of offending lashes, while nasolacrimal duct irrigation can help relieve an obstruction that increases the risk of infection. If a foreign body is in the eye, the eyelid will likely need to be everted and a slit lamp used. Conjunctival scrapings can be done. Before performing these, administer a topical anesthetic and antibiotic therapy.

When managing conjunctivitis, lab tests can provide useful information. A Gram stain can help identify bacterial characteristics, while a Giemsa stain is used to screen for chlamydia. Cultures may also be completed to identify viral and bacterial agents. A fungal culture is typically unnecessary, except in cases of corneal ulcers or known contamination of contact lens solutions, as observed in the epidemic of early 2006.[50] The type of inflammatory reaction can also help determine the cellular response. For instance, lymphocytes are likely to predominate in viral infections, eosinophils in allergic reactions, and neutrophils in bacterial infections.

In cases of viral conjunctivitis, viral isolation methods may help establish the diagnosis of acute follicular conjunctivitis; however, they are not indicated in chronic conjunctivitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and direct immunofluorescence monoclonal antibody staining are rapid and widely available detection methods.

Diagnosing allergic conjunctivitis may involve examining superficial scrapings, which can reveal eosinophils in severe cases. Eosinophils are only present in the deeper layers of the conjunctiva. So, if they are not found on conjunctival scrapings, it does not necessarily rule out the possibility of allergic conjunctivitis.

Many investigators have described the measurement of various inflammatory mediators in tears, such as immunoglobulin E, tryptase, and histamine, as indicators of allergic response.[51] In addition, skin testing may provide a definitive diagnosis and is highly practical and readily available.

Treatment / Management

When treating viral or bacterial conjunctivitis, educating the patient to reduce the spread of the infection is important. Bacterial conjunctivitis, while typically self-limiting, can be treated to help reduce the duration of symptoms. No significant outcome difference has been observed in trials comparing different types of ophthalmic antibiotic drops. While ointments typically last longer than drops, they tend to interfere with vision. Initial treatment for acute, mild bacterial conjunctivitis varies. Older-generation antibiotics are generally advised and are usually administered to the affected eye every 2 to 6 hours for 5 to 7 days. Later-generation antibiotics are reserved for more severe infections to minimize the development of resistance in the ocular surface flora.[52](A1)

In moderate to severe cases of bacterial conjunctivitis, the latest-generation fluoroquinolones are more suitable as they provide strong gram-negative and some gram-positive coverage. Antibiotic options are available as liquid solutions and topical ointments. Liquid solutions include polymyxin B/trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, and azithromycin. Bacitracin, erythromycin, and ciprofloxacin can be administered as an ointment. Fluoroquinolones should be prescribed for contact lens wearers to provide empiric coverage for Pseudomonas.

The recommended treatment for gonococcal conjunctivitis is ceftriaxone 1 gm intramuscular (IM); the recommendation is to treat concurrent chlamydial infection with 1 gm azithromycin by mouth (PO). The neonatal dosing for gonococcal conjunctivitis is 25 to 50 mg/kg ceftriaxone intravenous (IV)/IM not exceeding 250 mg, with 20 mg/kg azithromycin PO once daily for 3 days.

Viral conjunctivitis due to adenoviruses is self-limiting, and treatment should target symptomatic relief with cold compresses and artificial tears. Povidone-iodine 0.8% may be a potential option to decrease contagiousness in patients with adenoviral infections.[53]

Patients with herpes simplex keratitis should receive antiviral therapy. Mild infections may be treated with trifluridine 1% drops every 2 hours or 8 to 9 times a day for 10 to 14 days, topical ganciclovir 0.15% gel 1 drop 5 times a day until epithelium heals and then 3 times daily for 1 week, or acyclovir 400 mg PO 5 times a day for 7 to 10 days to limit epithelial toxicity. Patients should have a follow-up with an ophthalmologist within 2 to 5 days to monitor for complications.

Treatment of herpes zoster conjunctivitis includes a combination of oral antivirals and topical steroids; however, steroids should only be part of therapy in consultation with ophthalmology. Antiviral doses differ from those used for herpes simplex and consist of acyclovir 800 mg PO 5 times a day, famciclovir 500 mg PO 3 times a day, or valacyclovir 1 g PO 3 times a day, each for 7 to 10 days.

A study by Wilkins et al observed the effect of topical steroids compared with hypromellose in comforting patients with acute presumed viral conjunctivitis. They reported that a short course of topical dexamethasone in acute follicular conjunctivitis cases thought to have viral origin was not harmful.[54](B2)

Steroid use with antibiotics is controversial, and studies report mixed results in reducing corneal scarring.[55][56] Unfortunately, steroids may slow the healing rate, increase the risk of corneal melting, and increase the risk of elevated intraocular pressure.(A1)

Lastly, the treatment for allergic conjunctivitis consists of allergen avoidance, artificial tears, cold compresses, and a wide range of topical agents. Topical agents include topical antihistamines alone or in combination with vasoconstrictors, topical mast cell inhibitors, and topical glucocorticoids for refractory symptoms. Oral antihistamines can also be used in moderate to severe cases of allergic conjunctivitis.

Patients with moderate to severe pain, vision loss, corneal involvement, severe purulent discharge, conjunctival scarring, recurrent episodes, lack of response to therapy, or herpes simplex virus keratitis should receive a prompt referral to an ophthalmologist. In addition, those requiring steroids, contact lens wearers, and patients with photophobia should also be referred.[3][6][46](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

There are many emergent and non-emergent causes of eye redness. When diagnosing conjunctivitis, ruling out the emergent causes that can lead to vision loss is essential. The differentials for conjunctivitis include:

- Glaucoma

- Iritis

- Keratitis

- Episcleritis

- Scleritis

- Pterygium

- Corneal ulcer

- Corneal abrasion

- Corneal foreign body

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage

- Blepharitis

- Hordeolum

- Chalazion

- Contact lens overwear

- Dry eye

Some signs and symptoms that point to a diagnosis other than conjunctivitis include localized redness, redness that does not involve the entire conjunctiva, ciliary flush, elevated intraocular pressure, vision loss, moderate to severe pain, hypopyon (white or whitish-yellow collection of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber), hyphema (collection of blood in the anterior chamber), pupil asymmetry, decreased pupillary response, and trouble opening or keeping the eye open.

The clinician must recognize eye conditions such as angle-closure glaucoma, iritis, infectious keratitis, corneal ulcer, foreign body, and scleritis. These conditions can cause vision loss and require an ophthalmologist to manage them.[57] Typically, the redness in keratitis, iritis, and angle-closure glaucoma will involve the entire bulbar conjunctiva but spare the tarsal conjunctiva. Additionally, patients presenting with glaucoma may have a semi-dilated pupil, corneal opacity, ciliary flush, and elevated intraocular pressure. In comparison, iritis, also called anterior uveitis, commonly presents with pain, blurred vision, photophobia, ciliary flush, and hypopyon. While hypopyon is frequently associated with iritis, it can be isolated or associated with other conditions, such as infectious keratitis or a corneal ulcer.

Compared to iritis, patients with infective keratitis often complain of a foreign body sensation and trouble opening or keeping the eye open. These symptoms are consistent with corneal involvement and can present with other corneal disorders such as corneal ulcer, abrasion, or foreign body.[58] Foreign body and orbital trauma can result in hyphema, which can also result in acute and permanent vision loss.

Scleritis typically presents with severe pain radiating to the face that is most felt in the morning and at night. Also associated with photophobia is pain with extraocular movement, tenderness to palpation, and scleral edema.[59] All patients with hypopyon, hyphema, suspected iritis, keratitis, scleritis, corneal ulcer, or corneal foreign body should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist within 12 to 24 hours of presentation, while patients with suspected angle-closure glaucoma should see an ophthalmologist as soon as possible.

Non-Emergent Diagnoses

Pterygium and episcleritis are typically associated with localized redness, which differs from the diffuse redness in conjunctivitis. Blepharitis, contact overuse, and dry eyes are similar in presentation to allergic conjunctivitis. These conditions commonly present with a foreign body sensation, itching, or burning. History of contact use, lack of blinking, and allergies/atopy are important in differentiating contact lens overwear, dry eyes, and allergic conjunctivitis, respectively. Crusting of the eyelids, marked erythema, and edema of the eyelid margins are most consistent with blepharitis. Lastly, a subconjunctival hemorrhage is due to bleeding of conjunctival vessels and appears as blood in the subconjunctival space rather than the typical injection or vessel dilation seen in conjunctivitis.[46][57][60]

Prognosis

Conjunctivitis is a common eye condition that is treatable and typically benign. The duration of symptoms varies depending on the type of conjunctivitis. Viral conjunctivitis usually worsens for about 4 or 5 days before improving over the next 1 to 2 weeks, with a total duration of 2 to 3 weeks. Bacterial conjunctivitis usually lasts 7 to 10 days, but taking antibiotics within the first 6 days of onset can shorten the duration. Mortality in the cases of bacterial conjunctivitis is due to the failure to recognize and promptly treat the underlying disease. Meningitis and sepsis caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae can be life-threatening.[61]

Complications

Complications of acute conjunctivitis are rare. However, patients who fail to show improvement within 5 to 7 days should have a referral to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation. Patients with herpes simplex conjunctivitis are at the highest risk of complications. Approximately 38.2% of patients with herpes simplex virus develop corneal complications, and 19.1% develop uveitis; these patients should always see an ophthalmologist for close re-evaluation.[47] Patients with Neisseria gonorrhoeae are also at high risk for corneal involvement and secondary corneal perforation and should be treated appropriately. Chlamydial conjunctivitis in the newborn can cause pneumonia and otitis media.[62]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

When dealing with conjunctivitis, most cases can be managed with conservative measures.[42] Patients should be given thorough counseling on how the condition can be contagious and how it is critical to maintain good hygiene practices. They should also be informed about the importance of taking medication regularly, the self-healing nature of some types of conjunctivitis, and the benefits of using cold compresses. Lastly, it is crucial to emphasize the significance of regular follow-up appointments. If left untreated, some types of conjunctivitis can cause corneal scarring and even loss of vision.[6]

Consultations

Usually, a general ophthalmologist can treat most cases of conjunctivitis in the outpatient department. However, if the diagnosis is uncertain or the condition is not improving, a cornea specialist should be consulted.[63]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Viral and bacterial conjunctivitis can spread through direct contact and have high transmission rates. Educating patients on prevention and emphasizing the importance of hand hygiene for patients, staff, family, and friends is crucial. Results from a study found that when swabbing the hands of infected patients, 46% resulted in positive cultures.[6] Patients should be instructed to avoid touching their eyes, shaking hands, sharing personal items such as cosmetics or towels, and avoiding swimming pools while infected. Patients with active conjunctivitis admitted to the hospital should be placed in isolation, and any medical instruments used in their care should be disinfected.[3][6][37]

Pearls and Other Issues

All cases of conjunctivitis should be meticulously evaluated with a slit lamp. Clinical signs such as follicles, papillae, superficial puncture keratitis, subepithelial keratitis, and shied ulcer can help to differentiate the various types of conjunctivitis.[42]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists play crucial roles in the collaborative approach to treating and managing conjunctivitis, each contributing their unique skills and expertise. Clinicians must identify and diagnose the diverse clinical presentations of conjunctivitis, differentiating the various causes. They should obtain consultations with ophthalmology based on their assessments. On the other hand, nurses excel in patient care, applying their knowledge to care for and educate patients. Pharmacists are vital in implementing evidence-based treatment strategies, selecting appropriate medications, and ensuring medication safety and interactions.

All health professionals must adhere to high ethical standards, prioritizing patient well-being and autonomy throughout the treatment journey. Effective interprofessional communication is essential for sharing critical information, discussing treatment plans, and providing holistic patient-centered care. Care coordination among team members enhances patient outcomes by facilitating seamless transitions between different phases of care and promoting a cohesive approach to management. By synergizing their skills, strategies, ethics, responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and care coordination, healthcare professionals can improve patient safety, enhance team performance, and ultimately achieve better patient-centered care when treating and managing conjunctivitis.

Media

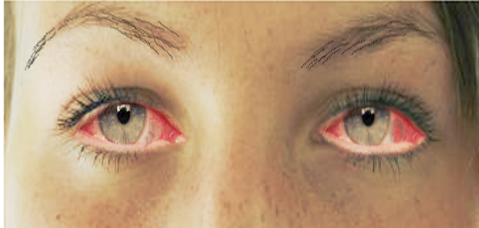

(Click Image to Enlarge)

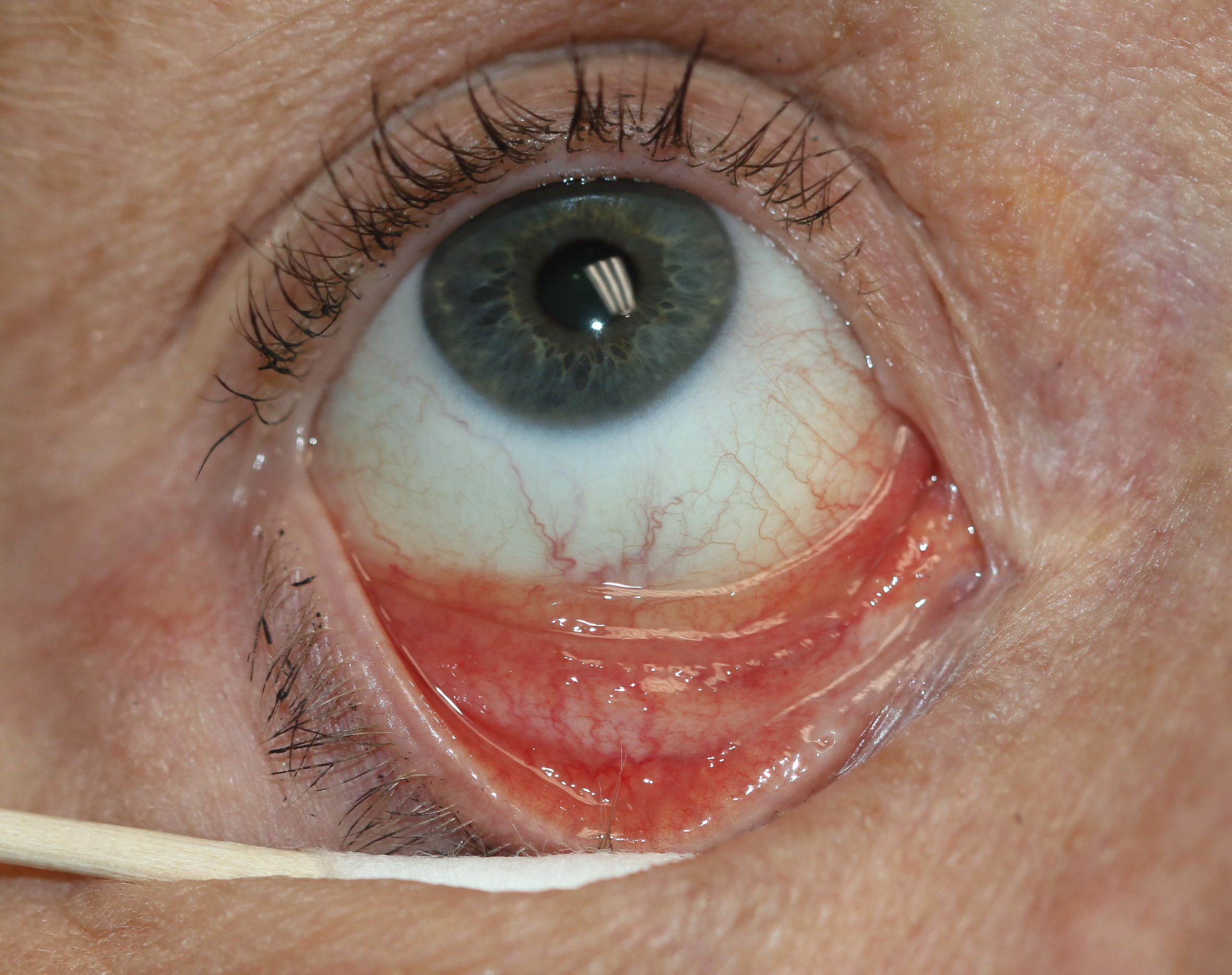

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Follicular Conjunctivitis. Inflammation is noted with viral infections like herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus infection, infectious mononucleosis, and chlamydial infections, as well as in reaction to topical medications and molluscum contagiosum. Follicular conjunctivitis has been described in patients with COVID-19. The inferior and superior tarsal conjunctiva and the fornices show gray-white elevated swellings about 0.5 to 1 mm in diameter and have a velvety appearance.

Contributed by Prof. BCK Patel MD, FRCS

References

Shekhawat NS, Shtein RM, Blachley TS, Stein JD. Antibiotic Prescription Fills for Acute Conjunctivitis among Enrollees in a Large United States Managed Care Network. Ophthalmology. 2017 Aug:124(8):1099-1107. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.04.034. Epub 2017 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 28624168]

Smith AF, Waycaster C. Estimate of the direct and indirect annual cost of bacterial conjunctivitis in the United States. BMC ophthalmology. 2009 Nov 25:9():13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13. Epub 2009 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 19939250]

Alfonso SA, Fawley JD, Alexa Lu X. Conjunctivitis. Primary care. 2015 Sep:42(3):325-45. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.001. Epub 2015 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 26319341]

de Laet C, Dionisi-Vici C, Leonard JV, McKiernan P, Mitchell G, Monti L, de Baulny HO, Pintos-Morell G, Spiekerkötter U. Recommendations for the management of tyrosinaemia type 1. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2013 Jan 11:8():8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-8. Epub 2013 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 23311542]

Sati A, Sangwan VS, Basu S. Porphyria: varied ocular manifestations and management. BMJ case reports. 2013 May 22:2013():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009496. Epub 2013 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 23704443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAzari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23:310(16):1721-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280318. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24150468]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHøvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta ophthalmologica. 2008 Feb:86(1):5-17 [PubMed PMID: 17970823]

Shields T, Sloane PD. A comparison of eye problems in primary care and ophthalmology practices. Family medicine. 1991 Sep-Oct:23(7):544-6 [PubMed PMID: 1936738]

Epling J. Bacterial conjunctivitis. BMJ clinical evidence. 2012 Feb 20:2012():. pii: 0704. Epub 2012 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 22348418]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTuraka K, Penne RB, Rapuano CJ, Ayres BD, Abazari A, Eagle RC Jr, Hammersmith KM. Giant fornix syndrome: a case series. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 Jan-Feb:28(1):4-6. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182264440. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21862948]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSatpathy G, Behera HS, Ahmed NH. Chlamydial eye infections: Current perspectives. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Feb:65(2):97-102. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_870_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28345563]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhosai SJ, Bailey RL, Gaynor BD, Lietman TM. Trachoma: an update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2012 Jul:23(4):288-95. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835438fc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22569465]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLansingh VC. Trachoma. BMJ clinical evidence. 2016 Feb 9:2016():. pii: 0706. Epub 2016 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 26860629]

Makker K, Nassar GN, Kaufman EJ. Neonatal Conjunctivitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722870]

Hoffman J. Adenovirus: ocular manifestations. Community eye health. 2020:33(108):73-75 [PubMed PMID: 32395030]

Giladi N, Herman J. Pharyngoconjunctival fever. Archives of disease in childhood. 1984 Dec:59(12):1182-3 [PubMed PMID: 6098226]

Meyer-Rüsenberg B, Loderstädt U, Richard G, Kaulfers PM, Gesser C. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis: the current situation and recommendations for prevention and treatment. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2011 Jul:108(27):475-80. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0475. Epub 2011 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 21814523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWright PW, Strauss GH, Langford MP. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. American family physician. 1992 Jan:45(1):173-8 [PubMed PMID: 1309404]

Saleh D, Yarrarapu SNS, Sharma S. Herpes Simplex Type 1. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489260]

Yoser SL, Forster DJ, Rao NA. Systemic viral infections and their retinal and choroidal manifestations. Survey of ophthalmology. 1993 Mar-Apr:37(5):313-52 [PubMed PMID: 8387231]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeza-Romero R, Navarrete-Dechent C, Downey C. Molluscum contagiosum: an update and review of new perspectives in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2019:12():373-381. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187224. Epub 2019 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 31239742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLa Rosa M, Lionetti E, Reibaldi M, Russo A, Longo A, Leonardi S, Tomarchio S, Avitabile T, Reibaldi A. Allergic conjunctivitis: a comprehensive review of the literature. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2013 Mar 14:39():18. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-39-18. Epub 2013 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 23497516]

Villegas BV, Benitez-Del-Castillo JM. Current Knowledge in Allergic Conjunctivitis. Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Feb 25:51(1):45-54. doi: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2020.11456. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33631915]

Kaur K, Gurnani B. Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35015458]

Sobolewska B, Zierhut M. [Atopic keratoconjunctivitis]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2014 May:231(5):512-7. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1368396. Epub 2014 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 24799170]

Kari O, Saari KM, Haahtela T. [Non-allergic eosinophilic conjunctivitis]. Duodecim; laaketieteellinen aikakauskirja. 2010:126(10):1145-50 [PubMed PMID: 20597344]

Resano A, Esteve C, Fernández Benítez M. Allergic contact blepharoconjunctivitis due to phenylephrine eye drops. Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology. 1999 Jan-Feb:9(1):55-7 [PubMed PMID: 10212859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDonshik PC, Ehlers WH, Ballow M. Giant papillary conjunctivitis. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2008 Feb:28(1):83-103, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.11.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18282547]

Pokroy R, Marcovich A. Self-inflicted (factitious) conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2003 Apr:110(4):790-5 [PubMed PMID: 12689904]

Schuster V, Seregard S. Ligneous conjunctivitis. Survey of ophthalmology. 2003 Jul-Aug:48(4):369-88 [PubMed PMID: 12850227]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDixon MK, Dayton CL, Anstead GM. Parinaud's Oculoglandular Syndrome: A Case in an Adult with Flea-Borne Typhus and a Review. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2020 Jul 29:5(3):. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5030126. Epub 2020 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 32751142]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLahoti S, Weiss M, Johnson DA, Kheirkhah A. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis: a comprehensive review. Survey of ophthalmology. 2022 Mar-Apr:67(2):331-341. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.05.009. Epub 2021 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 34077767]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSivaraman KR, Jivrajka RV, Soin K, Bouchard CS, Movahedan A, Shorter E, Jain S, Jacobs DS, Djalilian AR. Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis-like Inflammation in Patients with Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. The ocular surface. 2016 Jul:14(3):393-400. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.04.003. Epub 2016 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 27179980]

Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, Sollecito TP. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dental clinics of North America. 2013 Oct:57(4):611-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2013.07.003. Epub 2013 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 24034069]

Tolaymat L, Hall MR. Cicatricial Pemphigoid. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252376]

Oakley AM, Krishnamurthy K. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083827]

Ramirez DA, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Keenan JD. Epidemiology of Conjunctivitis in US Emergency Departments. JAMA ophthalmology. 2017 Oct 1:135(10):1119-1121. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.3319. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28910427]

Wong AH, Barg SS, Leung AK. Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Recent patents on inflammation & allergy drug discovery. 2014:8(2):139-53 [PubMed PMID: 25000933]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceO'Callaghan RJ. The Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus Eye Infections. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Jan 10:7(1):. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7010009. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29320451]

Chu WK, Choi HL, Bhat AK, Jhanji V. Pterygium: new insights. Eye (London, England). 2020 Jun:34(6):1047-1050. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0786-3. Epub 2020 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 32029918]

Leung AKC, Hon KL, Wong AHC, Wong AS. Bacterial Conjunctivitis in Childhood: Etiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management. Recent patents on inflammation & allergy drug discovery. 2018:12(2):120-127. doi: 10.2174/1872213X12666180129165718. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29380707]

Azari AA, Arabi A. Conjunctivitis: A Systematic Review. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2020 Jul-Sep:15(3):372-395. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v15i3.7456. Epub 2020 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 32864068]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBielory L, Meltzer EO, Nichols KK, Melton R, Thomas RK, Bartlett JD. An algorithm for the management of allergic conjunctivitis. Allergy and asthma proceedings. 2013 Sep-Oct:34(5):408-20. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3695. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23998237]

Frary J, Petersen PT, Pareek M. Hutchinson's sign of ophthalmic zoster. Clinical case reports. 2020 Jan:8(1):219-220. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2596. Epub 2019 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 31998523]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeibowitz HM. The red eye. The New England journal of medicine. 2000 Aug 3:343(5):345-51 [PubMed PMID: 10922425]

Mahmood AR, Narang AT. Diagnosis and management of the acute red eye. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2008 Feb:26(1):35-55, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.10.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18249256]

Puri LR, Shrestha GB, Shah DN, Chaudhary M, Thakur A. Ocular manifestations in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Nepalese journal of ophthalmology : a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal of the Nepal Ophthalmic Society : NEPJOPH. 2011 Jul-Dec:3(2):165-71. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v3i2.5271. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21876592]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008 Feb:115(2 Suppl):S3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18243930]

Sambursky R, Tauber S, Schirra F, Kozich K, Davidson R, Cohen EJ. The RPS adeno detector for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2006 Oct:113(10):1758-64 [PubMed PMID: 17011956]

Alfonso EC, Cantu-Dibildox J, Munir WM, Miller D, O'Brien TP, Karp CL, Yoo SH, Forster RK, Culbertson WW, Donaldson K, Rodila J, Lee Y. Insurgence of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2006 Jul:124(7):941-7 [PubMed PMID: 16769827]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMimura T, Usui T, Yamagami S, Miyai T, Amano S. Relation between total tear IgE and severity of acute seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Current eye research. 2012 Oct:37(10):864-70. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.689069. Epub 2012 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 22595024]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBorkar DS, Acharya NR, Leong C, Lalitha P, Srinivasan M, Oldenburg CE, Cevallos V, Lietman TM, Evans DJ, Fleiszig SM. Cytotoxic clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified during the Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial show elevated resistance to fluoroquinolones. BMC ophthalmology. 2014 Apr 24:14():54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-54. Epub 2014 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 24761794]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMonnerat N, Bossart W, Thiel MA. [Povidone-iodine for treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis: an in vitro study]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2006 May:223(5):349-52 [PubMed PMID: 16705502]

Wilkins MR, Khan S, Bunce C, Khawaja A, Siriwardena D, Larkin DF. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of topical steroid in presumed viral conjunctivitis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Sep:95(9):1299-303. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.188623. Epub 2011 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 21252084]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSrinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Ravindran M, Lalitha P, O'Brien KS, Glidden DV, Ray KJ, Oldenburg CE, Zegans ME, Whitcher JP, McLeod SD, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Acharya NR, Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial Group. The steroids for corneal ulcers trial (SCUT): secondary 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. American journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Feb:157(2):327-333.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.025. Epub 2013 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 24315294]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSrinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, Ravindran M, Lalitha P, Ray KJ, Zegans ME, Acharya NR, Lietman TM, Keenan JD, Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial Group. Visual recovery in treated bacterial keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2014 Jun:121(6):1310-1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.12.041. Epub 2014 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 24612976]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWright C, Tawfik MA, Waisbourd M, Katz LJ. Primary angle-closure glaucoma: an update. Acta ophthalmologica. 2016 May:94(3):217-25. doi: 10.1111/aos.12784. Epub 2015 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 26119516]

Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the Management of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017 Nov:124(11):1678-1689. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.012. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 28942073]

Sainz de la Maza M, Molina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Doctor PP, Tauber J, Foster CS. Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 2012 Jan:119(1):43-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.013. Epub 2011 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 21963265]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrandt MT, Haug RH. Traumatic hyphema: a comprehensive review. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2001 Dec:59(12):1462-70 [PubMed PMID: 11732035]

Ullman S, Roussel TJ, Culbertson WW, Forster RK, Alfonso E, Mendelsohn AD, Heidemann DG, Holland SP. Neisseria gonorrhoeae keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1987 May:94(5):525-31 [PubMed PMID: 3601368]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchachter J, Lum L, Gooding CA, Ostler B. Pneumonitis following inclusion blennorrhea. The Journal of pediatrics. 1975 Nov:87(5):779-80 [PubMed PMID: 1185349]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWood M. Conjunctivitis: diagnosis and management. Community eye health. 1999:12(30):19-20 [PubMed PMID: 17491982]