Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Conjoint Tendon (Inguinal Aponeurotic Falx)

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Conjoint Tendon (Inguinal Aponeurotic Falx)

Introduction

The conjoint tendon, also known as the inguinal aponeurotic falx or Henle's ligament, is a condensation of tissue that runs through the lateral edge of the lower rectus sheath. It is located in the inferior abdomen and is formed from the common aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle and transverse abdominis muscle, although they can be separated.[1] The fibers turn inferiorly and insert into the crest of the pubis at the pectineal line immediately deep to the superficial inguinal ring. Medially, the fibers of the conjoint tendon fuse with the anterior wall of the rectus sheath, while laterally, the fibers may fuse with the interfoveolar ligament. The conjoint tendon makes up the main part of the medial portion of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. The conjoint tendon has an essential role in protecting a weak area in the abdominal wall in which a weakening of the conjoint tendon may lead to a direct inguinal hernia.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The conjoint tendon forms the medial part of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal.[3] It is located right behind the superficial inguinal ring. The inguinal canal is a small passage formed by aponeuroses of the abdominal musculature. The canal serves as a connection from the abdominal cavity to the pelvic structures. The conjoint tendon reinforces the medial aspect of the Hesselbach’s triangle.

Hesselbach’s triangle, also referred to as the inguinal triangle, includes the following borders:

- Medial: linea semilunaris

- Superolateral: inferior epigastric vessels

- Inferior: inguinal ligament

While the lateral abdominal muscles are the major stressors of the conjoint tendon, the conjoint tendon also receives force from its connection with the rectus abdominis tendon and the pubic plate distally.[4]

Embryology

The development of the rectus sheath starts with the formation of the somatopleure on the ventral wall. Afterward, at the fifth to sixth week of gestation, myotomes merge with the somatopleure and form the ventral and dorsal wall of the thoracoabdominal wall. These structures are then called the hypomerion and epimerion, respectively. The external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles all arise from the same source, the lateral portion of the hypomerion, along with their aponeuroses. Henle's ligament is thus considered the lateral portion of aponeurosis, formed from the internal abdominal oblique and transverus abdominis, and is a derivative of the hypomerion.[5]

Nerves

The conjoint tendon receives nerve supply from the ilioinguinal nerve (L1).

Muscles

Four walls create the inguinal canal, but the most pertinent portion is the posterior wall, as the conjoint tendon contributes most to this structure. The posterior wall forms from the transversalis fascia, conjoint tendon, and deep inguinal ring. The conjoint tendon derives from a common aponeurosis of the internal oblique and the transverse abdominalis muscles. Its insertion is into the crest of the pubis and pectineal line deep to the superficial inguinal ring medial to the crural fibers. On imaging, the resting conjoint tendon is more vertical than horizontal. The distal tendon can be seen posterior to the pyramidalis muscle, and the conjoint tendon is seen crossing the junction of the middle and outer third of the pubic crest.[6]

Physiologic Variants

The conjoint tendon is a fusion of muscle that forms from the internal oblique tendon and the transverses abdominis tendon. In some occurrences, the tendons can be entirely separate.[7]

Surgical Considerations

The surgical relevance of the conjoined tendon is anatomical consideration during inguinal hernia repair. Techniques such as McVay, Bassini, and Shouldice involve suturing through the conjoint tendon to repair the weakness of the inguinal canal floor.

A weakness in the conjoint tendon causes a type of direct herniation known as Bugosa herniation or a Gill-Ogilvie hernia.[8] This herniation usually presents in young, athletic males with well-developed abdominal muscles. Laparoscopic repair is performed to address the risk of hernia strangulation.

Clinical Significance

Hernias to the conjoint tendon are common in athletes, commonly known as a sports hernia[9]. The conjoint tendon physiologically supports the abdominal contents when increased intraabdominal stress occurs. The current hypothesis on the mechanism of injury is the "shutter effect," where the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle tenses with increased abdominal pressure. The imbalance of strong hip adductor muscles and the weaker lower abdominal muscles leads to a shearing force across the hemipelvis that can result in tearing of the transversalis fascia/anterior muscles.

Approximately 90% of sports hernias occur in men. The most common patient populations are athletes involved in activities such as running, kicking, sharp turns, changes in direction, or rapid acceleration and deceleration. Football, soccer, and hockey athletes are the most common. The primary symptom is groin pain with exercise. The pain is located on the lower rectus abdominis muscle and may extend to the suprapubic region. It may be subtle in the beginning but can present as a sudden aggravating pain in rare instances. The pain will usually appear the next day following the injury, with a feeling of hardness in the groin and difficulty rising from the bed. The pain wanes with rest and restarts immediately following intensive exercise. Sports hernias can be hard to differentiate from other processes with symptoms of chronic inguinal pain[10]. Rotation control and pelvic stability are two of the most critical factors in preventing injury. Those with previous abdominal and inguinal injuries are at a higher risk for reoccurrence.

The diagnosis of a sports hernia is mainly a clinical one. Imaging can be beneficial with an MRI or ultrasound. Patients will often experience severe aching, pain after activity, and upon exertion such as defecation or cough.[11] The patient will report increased pain with palpation of the inguinal area, and a Valsalva maneuver can elicit a bulge. The current recommendation for conservative care is for 6 to 8 weeks of rest. Corticosteroids and working with a physical therapist may also be beneficial in recovery. If the condition does not improve with conservative measures, laparoscopic repair has been shown to improve symptoms and pain relief.

Other Issues

The terminology of the conjoint tendon is often confusing and has multiple names. The terms conjoint (sometimes spelled conjoined) tendon, Henle's ligament, and falx inguinalis are sometimes referred to interchangeably.

Media

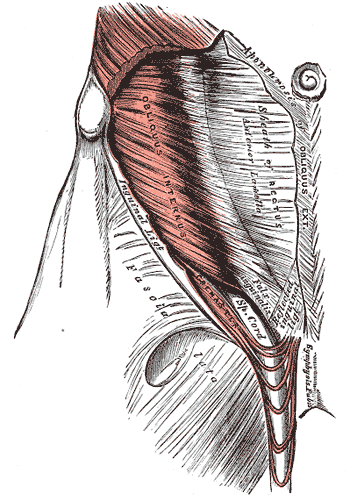

(Click Image to Enlarge)

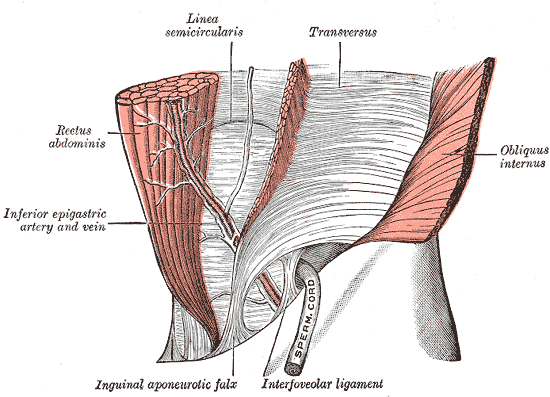

(Click Image to Enlarge)

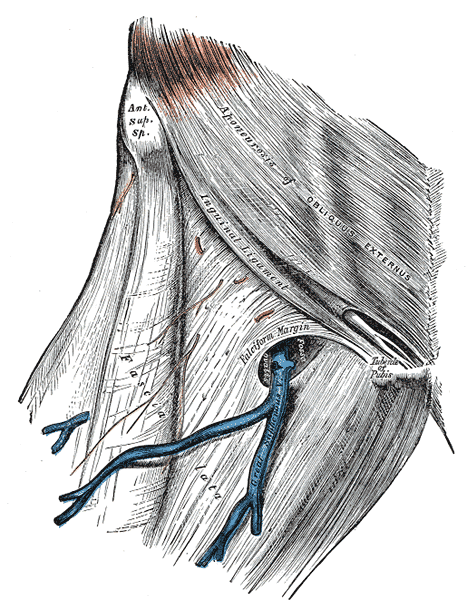

(Click Image to Enlarge)

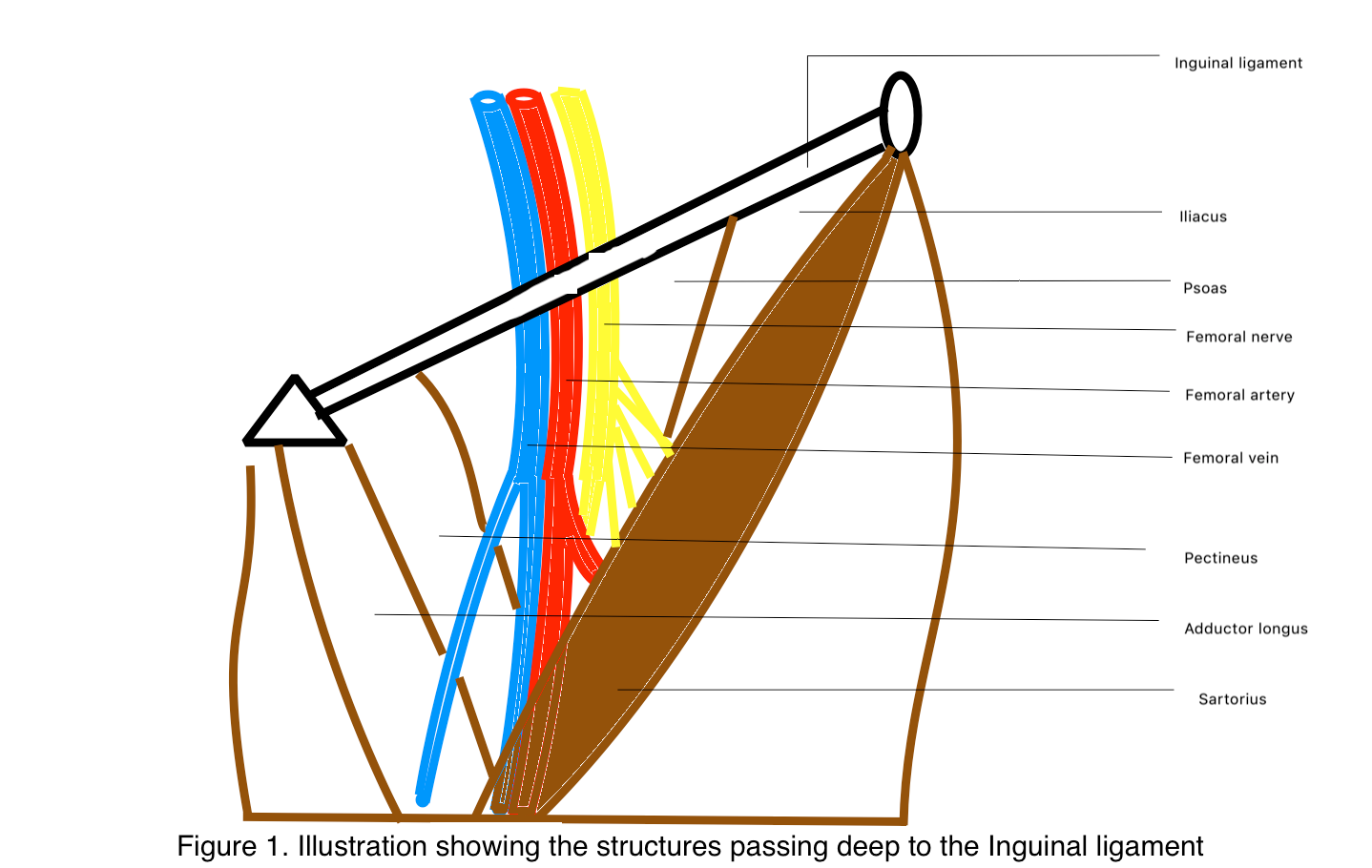

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Femoral Triangle. This illustration shows the femoral triangle and its contents and borders. The femoral nerve, artery, and vein pass deep to the inguinal ligament and enter the triangle. The borders of this region are the inguinal ligament (superior), adductor longus (medial), and sartorius (lateral). The femoral triangle floor is composed of the pectineus (medial), adductor longus (medial), and iliopsoas (lateral).

Contributed By Dr. Kavin Sugumar

References

Gnanadev R, Iwanaga J, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. Henle's Ligament: A Comprehensive Review of Its Anatomy and Terminology over Almost One and a Half Centuries. Cureus. 2018 Sep 26:10(9):e3366. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3366. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30510876]

Paajanen H, Hermunen H, Ristolainen L, Branci S. Long-standing groin pain in contact sports: a prospective case-control and MRI study. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2019:5(1):e000507. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000507. Epub 2019 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 31191965]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClar DT, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Femoral Region. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860736]

Campanelli G. Pubic inguinal pain syndrome: the so-called sports hernia. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2010 Feb:14(1):1-4. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0610-2. Epub 2010 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 20052510]

Sen T, Ugurlu C, Kulacoglu H, Elhan A. Falx inguinalis: a forgotten structure. ANZ journal of surgery. 2011 Mar:81(3):112-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05653.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21342379]

Drew MK, Osmotherly PG, Chiarelli PE. Imaging and clinical tests for the diagnosis of long-standing groin pain in athletes. A systematic review. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine. 2014 May:15(2):124-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.11.002. Epub 2013 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 24529632]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRamanathan S, Palaniappan Y, Sheikh A, Ryan J, Kielar A. Crossing the canal: Looking beyond hernias - Spectrum of common, uncommon and atypical pathologies in the inguinal canal. Clinical imaging. 2017 Mar-Apr:42():7-18. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.11.004. Epub 2016 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 27865126]

Read T, Maguire E. Bugosa hernia: a hernia of the conjoint tendon. ANZ journal of surgery. 2013 Apr:83(4):296. doi: 10.1111/ans.12088. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23556495]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaksoy M, Sekmen Ü. Sportsman hernia; the review of current diagnosis and treatment modalities. Ulusal cerrahi dergisi. 2016:32(2):122-9. doi: 10.5152/UCD.2015.3132. Epub 2015 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 27436937]

Piozzi GN, Cirelli R, Salati I, Maino MEM, Leopaldi E, Lenna G, Combi F, Sansonetti GM. Laparoscopic Approach to Inguinal Disruption in Athletes: a Retrospective 13-Year Analysis of 198 Patients in a Single-Surgeon Setting. Sports medicine - open. 2019 Jun 24:5(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s40798-019-0201-4. Epub 2019 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 31236737]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJoesting DR. Diagnosis and treatment of sportsman's hernia. Current sports medicine reports. 2002 Apr:1(2):121-4 [PubMed PMID: 12831721]