Introduction

Pulmonary hamartomas are noncancerous lung growths characterized by an abnormal mix of tissue types, including cartilage, connective tissue, fat, and epithelium. They represent the most common benign lung tumors in adults but are quite rare in children. A lesion first described by German pathologist Eugen Albrecht in 1904, hamartomas are generally benign tumors that may occur in the lungs, skin, heart, breast, and other body regions. The word hamartoma derives from hamartia, the Greek word for erroneous or faulty.[1] The cellular makeup of a hamartoma is an abnormal mixture of tissue components expected in the organ of origin, though organ architecture is usually not preserved within the lesion.

Pulmonary hamartomas grow slowly, are typically asymptomatic, and are often discovered incidentally.[1][2][3] These hamartomas grow slowly, are typically asymptomatic, and are often discovered incidentally. On chest imaging, they appear as well-defined, round, or lobulated structures, usually less than 3 cm in diameter, often located in the peripheral lung tissue. Therefore, neoplastic pressure erosion of adjacent structures is typically not noted.

Enucleation and wedge resections are the preferred surgical treatments. For larger, multiple, or hilar lesions that make less invasive surgeries impractical, lobectomy, sleeve resection, or pneumonectomy may be necessary. For patients with a risk of malignant transformation or coexisting primary lung cancer, anatomic resections are recommended. Endobronchial hamartomas can often be effectively removed via bronchoscopy.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Historically, no specific risk factors have been identified for pulmonary hamartoma. Occasionally, a relationship between lesions that have undergone sarcomatous transformation and specific genomic alterations has been described. Still, no screening guidelines are specifically designed for the early diagnosis of pulmonary hamartoma. Hamartomas are benign tumor-like malformations of disorganized tissue elements typically present within the affected organ. They are the most common benign neoplasm in the lung parenchyma. Endobronchial hamartomas account for 1.4% to 20% of all intrathoracic hamartomas and are the most frequent benign neoplasms in the endobronchial area. While most parenchymal hamartomas are asymptomatic, patients with an isolated endobronchial hamartoma experience symptoms that may include pneumonia, hemoptysis, cough, or dyspnea.[4]

Epidemiology

Pulmonary hamartomas occur with an incidence of 0.025% to 0.040% within the adult population.[5] They usually present in the fifth and sixth decade of life, with men being 4 times more likely to be affected than women.[2] Although still uncommon, these lesions are the most common benign pulmonary neoplasm, accounting for an estimated 77% of benign lung nodules and 8% of solitary lung lesions.[1][6] Most hamartomas occur in the peripheral parenchyma, with exceptions observed in the central chest wall. Additionally, approximately 10% of lesions present endobronchially.[1][7] Within the pediatric population, pulmonary hamartomas are significantly rarer.[2] After adjusting for age, sex, and ethnicity, individuals with pulmonary hamartomas have a 6.3 times higher risk of developing lung cancer compared to the general population.[8]

Histopathology

Also known as chondroid hamartomas, the histological makeup of these tumors is a mixture of mature mesenchymal tissue, like adipose tissue, cartilage, bone, or smooth muscle bundles, and fibromyxoid tissue—with varying proportions of each component. They are noninvasive, slow-growing, nodular lesions, sometimes displaying cleft-like spaces lined by respiratory epithelium.[2]

History and Physical

In adults, most parenchymal hamartomas are asymptomatic, identified incidentally. Depending on the location and size of the lesion, however, patients can still develop an array of complaints, including persistent coughing or wheezing, dyspnea, hemoptysis, rhonchi, higher likelihood of pneumonia, atelectasis, or even pneumothorax. Endobronchial masses additionally pose the danger of airway obstruction. Hamartomas that have become symptomatic require a thorough diagnostic approach, and surgical resection can become necessary.[2][9]

Evaluation

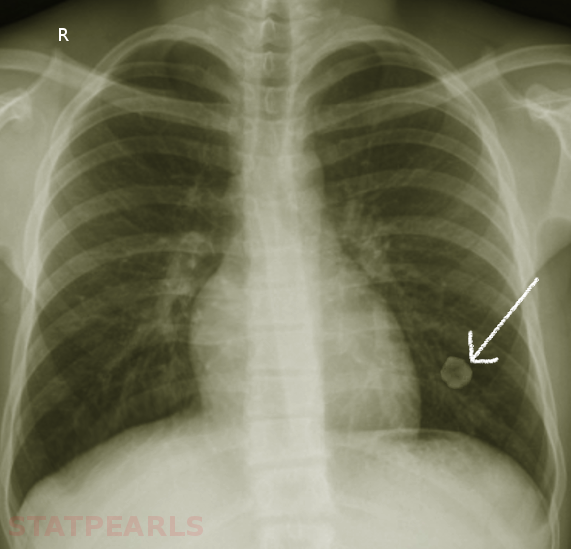

Hamartomas are often incidental findings on imaging and can mimic pulmonary malignancies. Once found, or in the case of asymptomatic hamartoma, multiple diagnostic strategies are available to determine the nature of the lesion. On imaging, eg, chest radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans, masses present as coin-shaped and solitary, with well-defined edges; they typically measure less than 4 cm in diameter. Calcification is present in 25% to 30% of patients. The “popcorn” or “comma-shaped” appearance of calcification is pathognomonic for hamartomas (see Image. Lung Hamartoma).[6][10] While CT imaging remains the gold standard, further diagnostic measures can become necessary. A fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scan can be useful in determining the rate of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake and, therefore, the metabolic rate of lesions with an indeterminate risk of malignancy.[6]

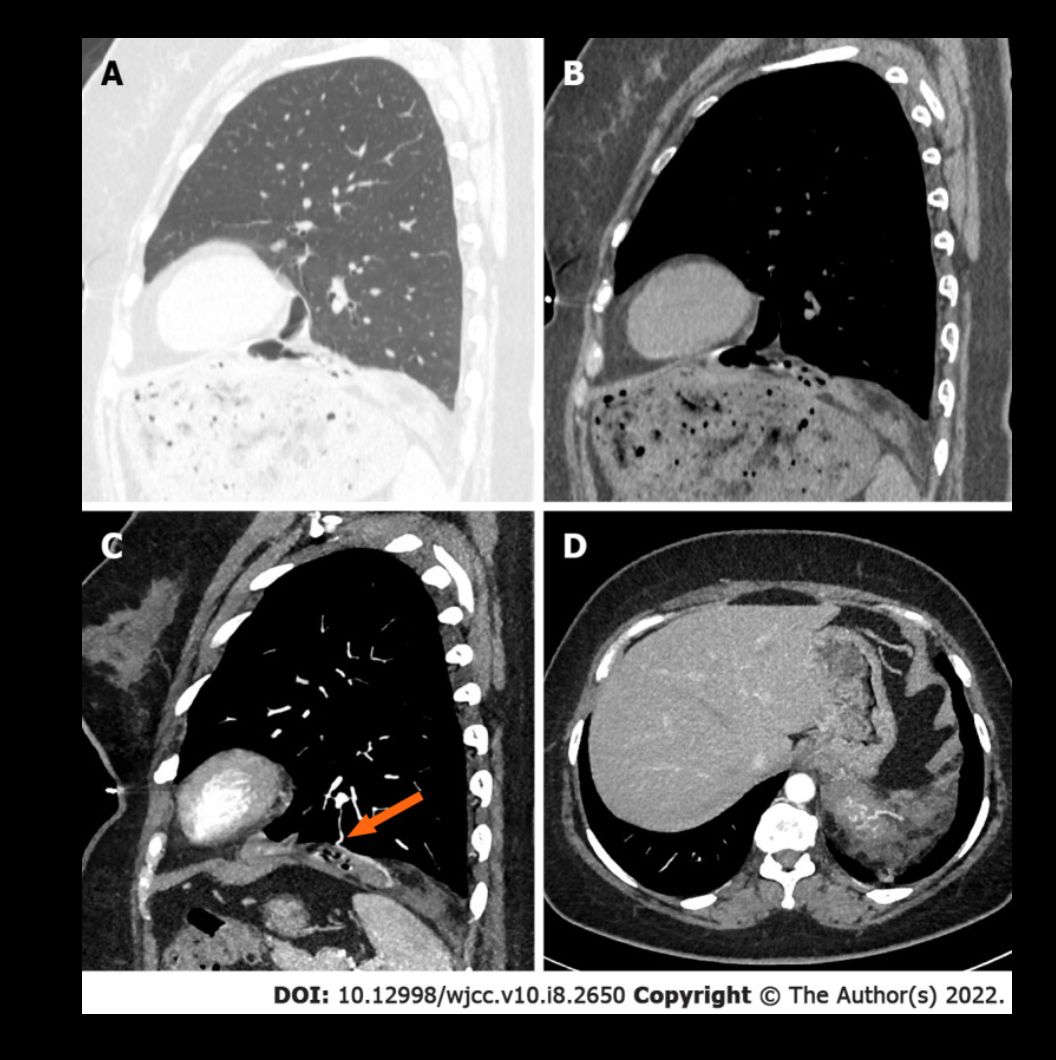

Especially in the case of lesions with an absent adipose component or those lacking the characteristic calcification pattern, biopsy becomes mandatory to rule out underlying malignancy. Bronchoscopy with fine needle aspiration is commonly the strategy of choice, though aspirations can be scant due to the density of the lesions. Masses with the typical coin appearance that fulfill CT criteria for hamartoma, including less than 4 cm in size, well-defined edges, detectable calcification, or fatty component, should remain subject to conservative follow-up with periodic observation. Resection is reserved for fast-growing or symptomatic masses or those in which the possibility of malignancy cannot be excluded.[11][12][13] See Image. Large Pulmonary Hamartoma.

Treatment / Management

Surgery remains the only definitive curative option available. In the event of surgery, preservation of functional lung tissue is the primary goal. Therefore, enucleation and wedge resections are the most common surgical choices, with more radical lobectomy or total pneumonectomy reserved for intense lesions, multiple or large lesions that make wedge resection impossible, or lesions adhering severely to the hilum of the lung. Obtaining intraoperative frozen sections is generally recommended to avoid overlooking underlying malignant potential.[14] (B2)

Most pulmonary hamartomas are smaller than 2.5 cm, and resection is typically unnecessary if the nodule exhibits classical signs of a hamartoma or if follow-up shows no growth. However, if the lesion is very large, resection may be required due to respiratory symptoms or the risk of malignancy. In the case report, primary resection was performed because a pulmonary teratoma was initially suspected based on the radiological appearance. Previous case reports have documented large hamartomas ranging from 8 to 20 cm, with patients experiencing significant symptoms (eg, dyspnea and massive hemoptysis). Such patients should be reviewed at an interprofessional team conference, where the proper course of evaluation and resection may be discussed.[15] (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

When encountering a possible hamartomatous lesion, the most significant consideration should be distinguishing the lesion from and excluding the possibility of underlying malignancy. Other benign pulmonary tumors should be considered upon exclusion of malignancy when deliberating the nature of a solitary pulmonary nodule, including infectious granuloma, lipoma, lipoid pneumonia, or pulmonary papilloma.[16] Also, though 90% of these are solitary occurrences, pulmonary hamartomas can appear in association with genetic syndromes.[6] Multiple pulmonary chondromatous hamartomas have been noted as manifestations of either the Carney triad or Cowden syndrome. The former is predominantly seen in young women and is characterized by the concurrent appearance of gastric leiomyoblastoma, pulmonary hamartoma, and extra-adrenal paraganglioma. Patients with Cowden disease often display multiple hamartomas, manifesting as mucocutaneous lesions, multiple benign tumors of internal organs, and an increased risk for several forms of cancer, including breast and digestive tract malignancies.[17][18]

The differential diagnosis includes benign solid tumors that exhibit ossification or calcification, including hamartomas, pulmonary amyloidomas, and pulmonary osteomas. Hamartomas typically present as solitary lung nodules and occasionally as endobronchial tumors. Histologically, they comprise hyaline cartilage, fibromyxoid stroma, smooth muscle cells, and adipose tissues. A characteristic feature of hamartomas is the presence of mesenchymal elements and epithelial tubules (clefts) resembling bronchiolar epithelium. On CT scans, hamartomas often show fat or calcification, with calcifications present in 5% to 50% of cases and fat in up to 50%.

Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis, or amyloidoma, is a localized type of amyloid deposition in the lung parenchyma. On CT, amyloidomas appear as solitary pulmonary nodules, multiple nodular lesions, or more diffuse patterns without specific diagnostic features. The histological diagnosis is confirmed by apple-green birefringence with Congo red staining under polarized light. Pulmonary osteoma refers to a bone lesion histologically made up of lamellar bone with Haversian canals, and the term should be reserved for actual bone lesions. Osteomas appear as very dense lesions (>885 HU) on CT scans, resembling normal bone cortex, and mature osteomas may also show central marrow. A report on pulmonary osteoma appearing as a solitary pulmonary nodule on CT has been reported. However, some experts have cautiously suggested that the case reported by Markert et al may not represent a true osteoma but rather a pulmonary hamartoma with ossification.[19]

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with lung hamartoma is generally excellent. Lesions are slow-growing, and in cases where symptoms are present and persistent, surgery is curative. Malignant transformation or subsequent malignancy are rare occurrences, and if patients adhere to a conservative observation schedule, malignant growths are likely to be diagnosed early on.[2][14]

Complications

Beyond the possibility of airway obstruction, with subsequent atelectasis or recurrent pneumonia, pulmonary hamartomas have, in rare cases, been noted to bear potential for sarcomatous transformation. Common signs of malignant alteration are the rapid growth of the lesion and systemic symptoms, including weight loss, weakness, or fatigue. Histologically, this malignant change may not always be apparent; however, macroscopic signs, like an invasion of adjacent tissue or distant metastases, may be present. In some cases, a possible relationship between the presence of genomic abnormalities of 12q14 and 6q21, encoding the high mobility group A, and the occurrence of pulmonary hamartoma has been observed. Also, incidence rates of lung cancer have been reported to be 6 times higher in patients with pulmonary hamartomas than in healthy subjects, making genetic predisposition to either malignant change or subsequent development of malignancy a possibility.[20][21]

Deterrence and Patient Education

No risk factors are associated with the development of pulmonary hamartomas, nor are there defined screening guidelines, considering the mostly sporadic nature of the lesions. Considering the risk, albeit small, of malignant change and development of subsequent malignancy, patients should be advised to adhere to a schedule of conservative observation in the form of periodic imaging and comparison with previous results.[14][20][21]

Pearls and Other Issues

Pulmonary hamartoma is a benign lung tumor that can cause pain or dyspnea when it reaches a significant size. While pulmonary hamartomas are more frequently observed in men and typically appear in the sixth and seventh decades of life, they can also occur in younger individuals and women, as demonstrated by this case. Accurate diagnosis is crucial for monitoring and determining whether intervention is necessary.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with lung lesions often initially come to the attention of primary care clinicians and nurse practitioners, who play a critical role in initial assessment and referral. Given the potential for malignancy, referral to an interprofessional team, including oncologists, thoracic surgeons, radiologists, and pulmonologists, is essential. Each team member contributes unique expertise. Radiologists use their technical skills to interpret imaging, though a definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy. Physicians and advanced practitioners coordinate care and ensure appropriate follow-up. If observation is the chosen management strategy, serial CT scans are recommended to monitor lesion growth, enhancing patient safety and outcomes. Effective interprofessional communication and care coordination are crucial for delivering patient-centered care, improving team performance, and ensuring optimal treatment decisions.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ahmed S, Arshad A, Mador MJ. Endobronchial hamartoma; a rare structural cause of chronic cough. Respiratory medicine case reports. 2017:22():224-227. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.08.019. Epub 2017 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 28913162]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaadi MM, Barakeh DH, Husain S, Hajjar WM. Large multicystic pulmonary chondroid hamartoma in a child presenting as pneumothorax. Saudi medical journal. 2015 Apr:36(4):487-9. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.4.10210. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25828288]

Özkan M. Pulmonary tumors in childhood. Turk gogus kalp damar cerrahisi dergisi. 2024 Jan:32(Suppl1):S73-S77. doi: 10.5606/tgkdc.dergisi.2024.25863. Epub 2024 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 38584790]

Girvin F, Phan A, Steinberger S, Shostak E, Bessich J, Zhou F, Borczuk A, Brusca-Augello G, Goldberg M, Escalon J. Malignant and Benign Tracheobronchial Neoplasms: Comprehensive Review with Radiologic, Bronchoscopic, and Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2023 Sep:43(9):e230045. doi: 10.1148/rg.230045. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37561643]

Mathangasinghe Y, Wijayawardhana S, Perera U, Punchihewa R, Pradeep S. Pathological characteristics of lung tumors in Sri Lanka 2017-2021. Thoracic cancer. 2024 Feb:15(4):347-349. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.15206. Epub 2024 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 38185770]

Lu Z, Qian F, Chen S, Yu G. Pulmonary hamartoma resembling multiple metastases: A case report. Oncology letters. 2014 Jun:7(6):1885-1888 [PubMed PMID: 24932253]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKishore M, Gupta P, Preeti, Deepak D. Pulmonary Hamartoma Mimicking Malignancy: A Cytopathological Diagnosis. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2016 Nov:10(11):ED06-ED07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22597.8844. Epub 2016 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 28050379]

Shukla I, Stead TS, Aleksandrovskiy I, Rodriguez V, Ganti L. Symptomatic Pulmonary Hamartoma. Cureus. 2021 Sep:13(9):e18230. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18230. Epub 2021 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 34692355]

Ge F, Tong F, Li Z. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hamartoma. Chinese medical sciences journal = Chung-kuo i hsueh k'o hsueh tsa chih. 1998 Mar:13(1):61-62 [PubMed PMID: 11717928]

Radosavljevic V, Gardijan V, Brajkovic M, Andric Z. Lung hamartoma--diagnosis and treatment. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2012:66(4):281-2 [PubMed PMID: 22919888]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRibet M, Jaillard-Thery S, Nuttens MC. Pulmonary hamartoma and malignancy. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1994 Feb:107(2):611-4 [PubMed PMID: 8302082]

Singh H, Khanna SK, Chandran V, Jetley RK. PULMONARY HAMARTOMA. Medical journal, Armed Forces India. 1999 Jan:55(1):79-80. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(17)30328-3. Epub 2017 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 28775580]

Raj NSS, Kodiatte TA, Vimala LR, Gnanamuthu BR. Giant cystic pulmonary hamartoma-images. Indian journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2022 Jan:38(1):99-101. doi: 10.1007/s12055-021-01239-5. Epub 2021 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 34898886]

Guo W, Zhao YP, Jiang YG, Wang RW, Ma Z. Surgical treatment and outcome of pulmonary hamartoma: a retrospective study of 20-year experience. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 2008 May 31:27(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-8. Epub 2008 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 18577258]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBorg M, Løkke A, Olsen KE, Hilberg O. Large pulmonary hamartoma: unusual presentation of a common abnormality. BMJ case reports. 2023 Oct 3:16(10):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2023-255064. Epub 2023 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 37788918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhan AN, Al-Jahdali HH, Irion KL, Arabi M, Koteyar SS. Solitary pulmonary nodule: A diagnostic algorithm in the light of current imaging technique. Avicenna journal of medicine. 2011 Oct:1(2):39-51. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.90915. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23210008]

Bini A, Grazia M, Petrella F, Chittolini M. Multiple chondromatous hamartomas of the lung. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2002 Dec:1(2):78-80 [PubMed PMID: 17669965]

Rodriguez FJ, Aubry MC, Tazelaar HD, Slezak J, Carney JA. Pulmonary chondroma: a tumor associated with Carney triad and different from pulmonary hamartoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2007 Dec:31(12):1844-53 [PubMed PMID: 18043038]

Hong P, Lee JS, Lee KS. Pulmonary Heterotopic Ossification Simulating a Pulmonary Hamartoma: Imaging and Pathologic Findings and Differential Diagnosis. Korean journal of radiology. 2022 Jun:23(6):688-690. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2022.0156. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35617995]

Itoga M, Kobayashi Y, Takeda M, Moritoki Y, Tamaki M, Nakazawa K, Sasaki T, Konno H, Matsuzaki I, Ueki S. A case of pulmonary hamartoma showing rapid growth. Case reports in medicine. 2013:2013():231652. doi: 10.1155/2013/231652. Epub 2013 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 24171003]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBasile A, Gregoris A, Antoci B, Romanelli M. Malignant change in a benign pulmonary hamartoma. Thorax. 1989 Mar:44(3):232-3 [PubMed PMID: 2705156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuo XW, Jia XD, Ji AD, Zhang DQ, Jia DZ, Zhang Q, Shao Q, Liu Y. Large cystic-solid pulmonary hamartoma: A case report. World journal of clinical cases. 2022 Mar 16:10(8):2650-2656. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2650. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35434052]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence