Introduction

Patients often come in with "droopy eyes" complaints, which refer to many issues. One common issue is upper eyelid dermatochalasis, but there may also be pseudoherniated fat or lacrimal gland ptosis. As people age, blepharoptosis, drooping of the eyelid, is common. Still, patients may not consider how brow ptosis, drooping of the eyebrow, can contribute to an aged appearance and even affect their vision. Surgeons must thoroughly evaluate the periorbital area to determine the best approach for each patient, including whether or not to perform a brow lift in conjunction with upper eyelid surgery.

Since Passot's first surgical brow lift in 1919, many techniques have been developed to improve results. The traditional coronal approach was the first modern approach, followed by trichophytic and pretrichial variants.[1] Direct, midforehead, temporal, endoscopic, and transblepharoplasty approaches were developed over the next 70 years.[2][3][4][5]

As technology in facial plastic surgery has advanced, and minimally invasive procedures have become more popular, endoscopic and transblepharoplasty techniques have gained popularity over open approaches. However, coronal incisions and their variants are still useful in certain situations. The choice of approach depends on whether any adjustment to the frontal hairline is necessary. A traditional coronal approach will commensurately elevate the hairline with the scalp strip's width excised. Pretrichial/trichophytic approaches tend not to elevate the hairline and may even be used to lower it if necessary. The choice between pretrichial and trichophytic approaches is generally based on surgeon and patient preference. The pretrichial approach places the incision directly anterior to the hairline, whereas the trichophytic approach runs a few millimeters posterior to the hairline to hide the scar. In some cases, such as for hairline adjustment, the incision may run partially anterior to the hairline and partially within it. This article will discuss the pretrichial brow lift approach and its benefits and limitations.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Brow Position

The notion of the ideal brow position undergoes continual evolution, mirroring shifts in fashion trends and the prevailing ideals of beauty. Traditionally, a man's brow is characterized as full and predominantly horizontal, aligning with the bony brow ridge. In contrast, the conventional depiction of a woman's brow medially places it at or slightly above the bony brow ridge, with the central and lateral portions positioned above it. The apex of the classical brow of a woman is typically situated laterally, between the lateral limbus and the lateral canthus, exhibiting a comparatively slender profile—thicker and rounded medially, yet thin and tapered laterally.[6]

However, this classical representation of the woman's brow should not be regarded as the sole criterion for periorbital femininity. Numerous women who are actresses and models celebrated for their beauty often sport flatter or fuller brows, challenging and expanding the conventional standards of attractiveness.

Fascial Layers

Familiarity with facial anatomy, from the level of the trichion down to the glabella and laterally to both lateral canthi, is critical for safe and effective pretrichial brow lifting, as dissection can be carried out in the subgaleal or subperiosteal planes.[7]

- The soft tissue layers, superficial to deep, at the central forehead's trichion level, are skin, subcutaneous fat, galea aponeurotica, loose areolar tissue, and pericranium.

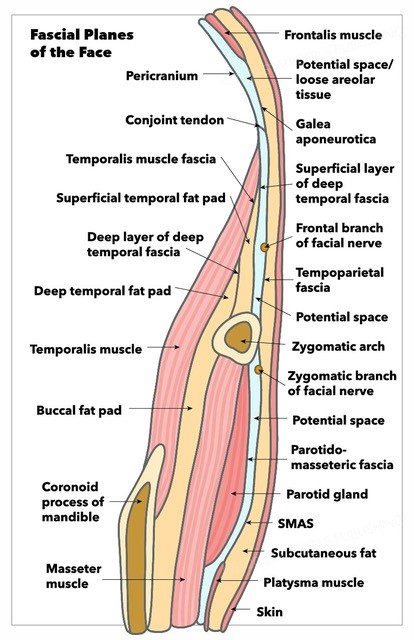

- At the level of the lateral canthus in the temporal region, the layers include skin, subcutaneous fat, temporoparietal fascia (TPF) or superficial temporal fascia, superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia, superficial temporal fat pad, deep layer of the deep temporal fascia, temporalis muscle, and pericranium. Inferior to this, at the level of the zygomatic arch, the deep layer of the deep temporal fascia invests the deep temporal fat pad. Superior to the superficial temporal fat pad, there is only a single layer of deep temporal fascia, which is synonymous with the temporalis muscle fascia (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face).

- The conjoint tendon separates the central and lateral compartments described above. The conjoint tendon is not a true tendon. Instead, it consists of a condensation of the superficial fascial layer (galea aponeurotica centrally and TPF laterally) and the deep fascial layers (pericranium centrally and temporalis fascia and pericranium laterally). This structure must be divided to provide adequate surgical exposure and mobilize the forehead sufficiently to elevate it.

Supratrochlear Nerve

The supratrochlear nerve constitutes a division of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve responsible for supplying sensation to the glabella and the medial forehead. This nerve ascends deep to superficial, offering sensory innervation to the central forehead. As it progresses, the nerve and accompanying vessels traverse the corrugator supercilii muscle.

Supraorbital Nerve

The supraorbital nerve comprises medial and lateral branches originating from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. This nerve provides sensation to the lateral brow and the lateral forehead. The supraorbital nerve emerges from the skull lateral to the supratrochlear nerve, precisely at the midpupillary line; in approximately 72.4% of cases, the nerve traverses a notch in the supraorbital rim. However, 27.6% of cases may pass through a true foramen.[8]

In instances where a notch is present, there is a potential limitation to the soft tissue's mobility, increasing the risk of traction injury when reflecting the forehead flap inferiorly. An osteotomy can be undertaken to convert a foramen into a notch to address this concern and enhance the mobilization of the forehead. The presence of a notch on 1 side does not reliably predict the same on the other, as asymmetry in this anatomical feature is commonplace.

Temporal Branch of the Facial Nerve

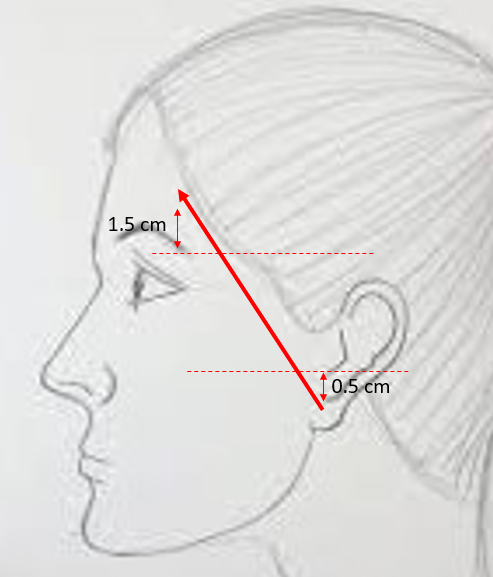

The facial nerve's temporal (frontal) branch faces potential risk during the lateral phase of brow lift dissection as it traverses beneath the undersurface or within the deep layers of the TPF. The Pitanguy line, a reference drawn from 0.5 cm below the tragus to 1.5 cm above the lateral margin of the brow, approximates the nerve's course (see Image. Temporal Branch Course).[9] There is a caveat: the nerve exhibits branching as it extends distally, rendering a single-line approximation inaccurate, particularly given variations in the lateral brow's position influenced by grooming practices and prior surgical interventions.[10] However, as a general guideline, the nerve typically avoids the region beneath the hair-bearing scalp, making procedures in that area comparatively safer.

Facial Mimetic Muscles

The following comprise the facial mimetic muscles:

- Frontalis: This muscle is contiguous with the galea aponeurotica and inserts into the dermis of the brow. Contraction of this muscle produces brow elevation and the formation of horizontal forehead rhytids.

- Corrugator supercillii: These paired muscles are situated along the supraorbital rims, originating from the superior aspect of the nasal bones and inserting into the dermis of the mid to lateral brow. They are responsible for vertical glabellar rhytids.

- Procerus: This is a fan-shaped muscle that depresses the medial brow. This muscle originates along the nasal bones and projects superiorly towards the medial heads of the brows; it is in the midline, superficial to the corrugator muscles, and produces horizontal glabellar rhytids.[11][12]

Arcus Marginalis

This is a fascial condensation along the orbital rim where the pericranium, periorbita, and orbital septum meet. Much like the conjoint tendon, this must be divided to mobilize and elevate the skin and soft tissue.

Indications

The primary indication for pretrichial brow lifting arises when there is clinically significant brow ptosis, typically reported by patients experiencing drooping eyebrows or difficulties seeing objects above eye level. Various approaches can be employed to address brow ptosis. Still, the pretrichial incision is particularly well-suited for patients content with their existing hairline position or those with high hairlines seeking adjustment or reshaping, such as in the context of facial feminization.[13]

Like other coronal-type techniques, the pretrichial incision offers excellent access to the frontal calvarium, periosteum, frontal sinus, and the naso-orbital-ethmoid (NOE) region. Additionally, the incision facilitates exposure and division of the corrugator muscles, effectively mitigating vertical glabellar rhytids, commonly referred to as "frown lines" or "number elevens." Furthermore, the superior exposure provided by pretrichial brow lifting positions it as a favorable choice for revision brow lifting procedures. However, the lift achieved with a pretrichial brow lift is on par with an endoscopic lift.[14][15]

To summarize, the most common indications for employing a pretrichial approach to brow lifting are the following:

- Revision brow lifting after minimally invasive surgery that did not produce the desired result

- Advancing the frontal hairline while simultaneously performing a brow lift for aging face indications [16]

- Advancing the frontal hairline while providing access for frontal cranioplasty in gender affirmation surgery for transgender females [17][18]

- Accessing the frontal sinus, NOE region, brain, or anterior skull base for post-traumatic reconstruction or oncologic resection

- Accessing the frontal pericranium for the development of an osteoplastic flap

Contraindications

Given the extended length of the pretrichial incision, primary contraindications to its use revolve around the possibility of an aesthetically undesirable scar. Patients with receding hairlines or those anticipating future recession should avoid the pretrichial approach. Likewise, patients with a history of suboptimal scarring, or those prioritizing minimal visibility of scars, may find alternative methods more suitable, employing shorter incisions or concealing them within the hair-bearing portion of the scalp.

Coronal approaches, by design, lift the forehead as a cohesive unit, making it challenging to apply significantly different tension on 1 side compared to the other. Consequently, patients with pronounced brow asymmetry might find better outcomes with a technique that addresses each brow independently, such as direct, temporal, or transblepharoplasty lifts. Lastly, individuals with low-lying hairlines may not be optimal candidates for pretrichial brow lifting due to the potential for slight advancement of the hairline during closure.

Equipment

The following equipment is needed to perform the pretrichial brow lift:

- 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in syringes with 27- to 30-gauge hypodermic needles

- #15 scalpel blade

- #3 Bard-Parker scalpel handle

- Freer elevator

- 10 mm Joseph double prong skin hooks

- 1/4 curved Daniel endoscopic forehead elevator

- Metzenbaum scissors

- Adson-Brown forceps

- 3 mm straight, unguarded osteotome and mallet (in case of a supraorbital notch)

- Monopolar and bipolar electrocautery

- Raney gun with extra clips

- 3-0 polyglactin suture

- 4-0 poliglecaprone suture

- 5-0 gut suture

- Suture scissors

- Antibiotic ointment

- Cotton gauze roll and compressive wrap for dressing

Personnel

The following personnel are necessary for performing the pretrichial brow lift procedure:

- Surgeon

- Surgical assistant

- Surgical scrub technician

- Circulating nurse

- Anesthesia provider

Preparation

Before proceeding with surgery, engaging in a thorough discussion with the patient is imperative, addressing the anticipated surgical outcomes, the postoperative experience, and the potential risks associated with the procedure. Effectively managing expectations has the dual benefit of enhancing the patient's perception of the surgical results and reducing the likelihood of postoperative inquiries to the surgeon's office. Furthermore, these discussions foster a strong doctor-patient rapport, potentially offering a protective element against litigation in case of unfavorable surgical outcomes.

When brow lifting and blepharoplasty are undertaken for functional reasons, documenting visual field deficits is crucial for interactions with third-party payers. Equally important is the establishment of standard preoperative photography. Essential images encompass frontal views in repose and with brow elevation, at a minimum. If blepharoplasty is part of the plan, additional profile views of the eyes in neutral, closed, and upward positions may prove beneficial. Beyond aiding in surgical planning and serving as medicolegal documentation when paired with postoperative images, these preoperative photographs should be prominently displayed in the operating room during the procedure for easy reference.

Technique or Treatment

After the patient has signed consent and is then prepped, marked, and draped, 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine is injected into the scalp from the temporal fossa across the entire forehead, up 1 to 2 cm into the frontal hairline. On the contralateral side, the injection is administered into the temporal fossa. In the central region, the local anesthetic is introduced down to the bone, and laterally, it extends to the level of the temporalis muscle fascia. Alternatively, a tumescent solution can be employed instead of 1% lidocaine. This approach may be particularly advantageous when aiming to minimize the risk of toxicity, especially if the patient is undergoing additional aging face procedures that necessitate higher doses of local anesthetics.

The incision is carefully marked, beginning just above the root of the helix, ascending through the temporal hair tuft, and culminating at the hairline, where it transitions from the vertical temporal segment to the horizontal frontal segment. The preoperative hairline contour and any desired reshaping considerations determine where the incision departs from the hair-bearing scalp to emerge anterior to the hairline. Notably, the segment of the incision that traverses just in front of the central frontal hairline is deliberately irregular, mirroring the natural irregularities of the hairline to conceal the ultimate scar effectively. Subsequently, the incision extends into the contralateral temporal hair tuft and descends towards the root of the helix (see Image. Preoperative Marking of the Pretrichial Brow Lift Incision).

Precision is crucial when beveling the incision, with the choice between aligning it parallel or perpendicular to the hair follicles depending on the surgeon's preference. Some surgeons advocate for a parallel bevel, asserting that it reduces the risk of follicular injury. Conversely, others favor a perpendicular bevel, contending that it allows hairs to grow through the scar, providing better camouflage. The incision itself is executed using a #15 blade scalpel, and controlled hemostasis can be achieved through bipolar electrocautery or the application of Raney clips.

In the central region, between the temporal lines, the incision should extend at least through the galea aponeurotica and possibly down to the periosteum, contingent upon the desired dissection plane. Surgeons may opt for a subgaleal approach that preserves the periosteum's adherence to the calvarium, or they may prefer a subperiosteal approach. In either case, maintaining the periosteum intact and connected to the supraorbital vessels facilitates the elevation of a pericranial flap if required. As the incision progresses laterally, it should reach through the temporalis fascia, stopping at the level of the temporalis muscle.

In the case of a subgaleal plane, blunt finger dissection proves adequate for elevating the central forehead, although using Metzenbaum scissors for spreading may be more comfortable. Alternatively, for a subperiosteal dissection, the elevation of the periosteum begins with a Freer elevator (see Image. Periosteum Elevation With a Freer Elevator). The elevation progresses toward the supraorbital rims, employing a 1/4 curved Daniel forehead elevator. Elevation can proceed blindly until reaching 1 to 2 cm superior to the supraorbital rims. In scenarios where hairline adjustment is planned, 4 to 5 cm of back elevation in a subgaleal or intragaleal plane posterior to the incision may also be useful.

Moving on to lateral dissection, the TPF is incised, unveiling the temporalis muscle fascia. Subsequently, the TPF is elevated off the temporalis fascia, progressing from lateral to medial until encountering the conjoint tendon (see Image. Temporoparietal Fascia Elevation). By meticulously preserving this plane, the surgeon ensures the frontal branch of the facial nerve is elevated within the flap and remains intact, even if not directly visualized during the dissection. Once the conjoint tendon is identified, a Freer elevator perforates it from lateral to medial, positioned 2 to 3 cm superior to the zygomaticofrontal suture. The Freer is then adeptly maneuvered both superiorly and inferiorly to avulse the conjoint tendon from the calvarium, creating a seamless continuity between the central and lateral dissection compartments. The same technique is subsequently applied contralaterally.

This comprehensive exposure allows the forehead flap to be delicately reflected inferiorly onto the nose. Should the flap require assistance to maintain this position, an assistant can gently retract it using double-pronged skin hooks. Exercise caution during retraction, avoiding placement in areas where the frontal branches of the facial nerves are located. Direct visualization is then employed to expose the supraorbital rims and the glabella. While the supratrochlear neurovascular bundles may not always be visible, encountering the supraorbital bundles is typically expected.

The supraorbital neurovascular bundles should be released from their notches to facilitate complete reflection of the forehead flap and expose the supraorbital rims. If foramina are present instead of notches, gentle osteotomies along the inferior borders of the foramina, both laterally and medially, with a 3 mm osteotome, can release the bundles and permit flap reflection without inducing neuropraxia.

Regardless of the initial dissection plane, the periosteum should be elevated precisely at the level of the supraorbital rim and extend approximately 1 cm superior and lateral to it. This exposure and periosteal elevation should run seamlessly from the level of the left lateral canthus to the right. In cases where the elevation was conducted in a subgaleal plane and a pericranial flap was planned, the flap would need to be elevated at this stage. Alternatively, suppose the dissection occurred in a subperiosteal plane, and a pericranial flap was intended. In that case, the pericranial flap may be elevated from the undersurface of the forehead flap at any point during the procedure (see Image. Pericranial Flap Elevation).

Following the complete exposure of the supraorbital rim, it is imperative to divide the arcus marginalis sharply and spread aggressively. This step is crucial for achieving effective elevation of the brows, and the failure to do so remains the primary reason for inadequate brow elevation. Concurrent procedures, such as frontal cranioplasty, should be executed at this juncture.

Subsequently, the forehead flap is meticulously redraped, and superior retraction using skin hooks is applied until the desired brow height is attained. Some surgeons employ various methods to secure the flap's elevated position before closure. In this regard, the authors of this article endorse using either resorbable polymer anchors or 2-0 silk sutures anchored to the calvarium with resorbable pins. Anchors ensure brow elevation by maintaining superior tension and can be strategically positioned to exert anterior tension for hairline advancement if necessary. Palpability issues with anchors often lead to patient complaints; hence, using resorbable pins and sutures may be considered an alternative (see Image. Anchors in Pretrichial Brow Lift and Image. Anchors in Coronal Brow Lift).

The closure begins by securing the incision with sutures or staples, allowing for the assessment of excess tissue that can be safely removed. In the case of most older cisgender female face patients, this typically involves the removal of a lengthy, elliptical strip of scalp. However, for patients seeking hairline adjustment, the approach becomes more nuanced; this may include the removal of non-hair-bearing skin laterally and hair-bearing skin from the widow's peak area, aiming to diminish the characteristic M-shape often associated with a receding male hairline. This technique finds particular relevance in facial feminization procedures.

Following the removal of excess tissue, the remainder of the closure ensues, ensuring appropriate hemostasis. The closure is executed in layers, initially addressing the galea aponeurotica/TPF layer, followed by robust sutures penetrating the skin surface with 3-0 and 5-0 resorbable sutures, respectively, unless staples are employed for the superficial layer. While sutures in the deep dermis between the surface layer and the galea layer may offer additional tensile strength, many surgeons avoid this layer due to concerns about suture extrusion over time, contrary to planned absorption. Antibiotic ointment is then applied over the sutures or staples. Although the placement of a drain is discretionary, and a pressure dressing may be utilized, it's crucial to ensure that the dressing applies pressure to the forehead without depressing the brows, for instance, with a Barton-type dressing.

Complications

Beyond the standard complications associated with any soft tissue surgical procedure, such as pain, bleeding, infection, and suboptimal scarring, pretrichial brow lifting presents specific potential adverse outcomes. These include but are not restricted to, numbness affecting a portion or the entirety of the forehead due to possible injury to the supraorbital or supratrochlear nerves. There's also a risk of weakness in brow elevation or brow ptosis arising from damage to the frontal branch of the facial nerve.

Additional potential complications include the formation of hematoma or seroma, brow asymmetry, inadequate brow elevation, excessive brow elevation, hairline irregularities, and the possibility of alopecia at the scar line. Communicate to patients that they should anticipate experiencing numbness in the scalp posterior to the incision, and this sensation may not fully resolve over time.[19] Providing thorough information about these potential outcomes is essential for informed decision-making and patient satisfaction.

Clinical Significance

In the current era, which emphasizes minimally invasive techniques for facial aesthetic surgery, traditional open approaches, such as pretrichial brow lifting, persist as valuable options for a diverse range of patients. This method proves particularly advantageous when both brow elevation and adjustment of the frontal hairline are requisite. Pretrechial brow lift is frequently employed for female transgender patients seeking the elevation of the hair-bearing brow, along with the simultaneous reduction of the bony supraorbital ridges and reshaping of the hairline, achievements readily accomplished through the pretrichial incision.

Even in scenarios where neither the hairline nor the brow position holds paramount importance, such as in cases involving frontal sinus fractures, NOE fractures, and anterior skull base tumors, a pretrichial approach may remain preferable over a traditional coronal incision, especially for patients with short hair who wish to avoid a conspicuous scar across the vertex of the scalp. While coronal-type brow lift approaches may be more time-consuming and likely to leave a visible scar than minimally invasive methods, they deliver a comparable degree of elevation and offer superior exposure to the frontal calvarium. Thus, pretrichial brow lifting is a significant and versatile component of the facial surgeon's repertoire.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In pretrichial brow lifting procedures, a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals is essential for optimizing patient-centered care, outcomes, patient safety, and team performance. Physicians, particularly surgeons specializing in facial aesthetics, must possess advanced skills in pretrichial brow lifting techniques, staying abreast of the latest advancements, and adhering to patient safety protocols. Advanced practitioners, such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants, contribute by providing comprehensive preoperative and postoperative care, monitoring patient recovery, and ensuring continuity in treatment plans.

Nurses are pivotal in pretrichial brow lifting and responsible for perioperative patient care, including assisting in the operating room, managing postoperative recovery, and educating patients on self-care. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring proper medication management, including pain control and minimizing potential drug interactions. Effective interprofessional communication is paramount to align treatment goals, address patient concerns, and coordinate care seamlessly. Regular team meetings facilitate the exchange of insights, ensuring a holistic understanding of the patient's needs. This collaborative effort enhances the overall patient experience, safety, and effectiveness of midface lifting procedures.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fascial Planes of the Face and Musculature. This illustration depicts the fascial planes of the face, highlighting the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and the location of the facial nerve.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Paul MD. The evolution of the brow lift in aesthetic plastic surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2001 Oct:108(5):1409-24 [PubMed PMID: 11604652]

Jawad BA, Raggio BS. Direct Brow Lift. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644687]

Patel BC, Malhotra R. Mid Forehead Brow Lift. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571073]

Raggio BS, Winters R. Endoscopic Brow Lift. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424804]

Paul MD. Subperiosteal transblepharoplasty forehead lift. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 1996 Mar-Apr:20(2):129-34 [PubMed PMID: 8661593]

Griffin GR, Kim JC. Ideal female brow aesthetics. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2013 Jan:40(1):147-55. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2012.07.003. Epub 2012 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 23186765]

Karimi N, Kashkouli MB, Sianati H, Khademi B. Techniques of Eyebrow Lifting: A Narrative Review. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2020 Apr-Jun:15(2):218-235. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v15i2.6740. Epub 2020 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 32308957]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNanayakkara D, Manawaratne R, Sampath H, Vadysinghe A, Peiris R. Supraorbital nerve exits: positional variations and localization relative to surgical landmarks. Anatomy & cell biology. 2018 Mar:51(1):19-24. doi: 10.5115/acb.2018.51.1.19. Epub 2018 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 29644106]

Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

Gosain AK, Sewall SR, Yousif NJ. The temporal branch of the facial nerve: how reliably can we predict its path? Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1997 Apr:99(5):1224-33; discussion 1234-6 [PubMed PMID: 9105349]

Kashkouli MB, Abdolalizadeh P, Abolfathzadeh N, Sianati H, Sharepour M, Hadi Y. Periorbital facial rejuvenation; applied anatomy and pre-operative assessment. Journal of current ophthalmology. 2017 Sep:29(3):154-168. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2017.04.001. Epub 2017 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 28913505]

De Jong R, Hohman MH. Brow Ptosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809597]

Spiegel JH. Scalp Advancement and the Pretrichial Brow Lift. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2018 Apr:34(2):145-149. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1636920. Epub 2018 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 29631283]

Dayan SH, Perkins SW, Vartanian AJ, Wiesman IM. The forehead lift: endoscopic versus coronal approaches. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2001 Jan-Feb:25(1):35-9 [PubMed PMID: 11322395]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePuig CM, LaFerriere KA. A retrospective comparison of open and endoscopic brow-lifts. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2002 Oct-Dec:4(4):221-5 [PubMed PMID: 12437426]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFattahi T. Trichophytic brow lift: a modification. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Mar:44(3):371-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.10.007. Epub 2014 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 25457833]

Sykes JM, Dilger AE, Sinclair A. Surgical Facial Esthetics for Gender Affirmation. Dermatologic clinics. 2020 Apr:38(2):261-268. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.10.011. Epub 2019 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 32115136]

Hohman MH, Teixeira J. Transgender Surgery of the Head and Neck. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33760488]

Lighthall JG, Wang TD. Complications of forehead lift. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2013 Nov:21(4):619-24. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2013.07.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24200380]